Imagine stumbling upon a book filled with elaborate illustrations and elegant script, only to realize that nobody in the entire world can read a single word of it. You’d be fascinated, right? Maybe even a little unnerved. That’s exactly the sensation that has gripped scholars, cryptographers, and mystery enthusiasts for over a century.

Welcome to the world of the Voynich Manuscript, an enigma wrapped in vellum pages that refuses to yield its secrets. It’s a puzzle that looks solvable but has defeated every attempt to crack it. The more you stare at its pages, the more tantalizing it becomes, as if the book itself is daring you to try.

A Book Dealer’s Discovery That Changed Everything

In 1912, a rare book dealer named Wilfred Voynich acquired an ancient manuscript that he claimed would startle the scientific world. He bought it along with 29 other manuscripts from the Jesuit College at Frascati near Rome, and spent the next seven years attempting to interest scholars in deciphering the script. Voynich had toured the United States displaying pages from his mysterious find, making bold claims about medieval knowledge hidden within.

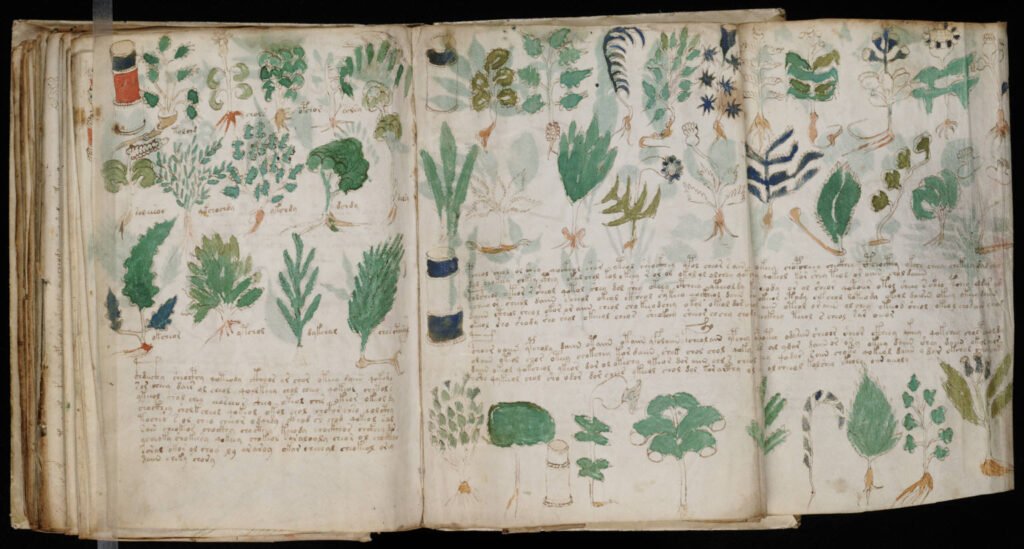

The manuscript’s pages are crowded with intricate drawings of plants and herbs, diagrams of stars and planets, and even some drawings of nude women bathing. It appeared to be a typical medieval treatise, similar to those produced by alchemists centuries earlier. Yet something about it was deeply wrong. The text accompanying these illustrations was written in a script nobody recognized.

After Voynich’s death in 1930, the manuscript passed to his widow Ethel, and eventually made its way to Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in 1969. Today, it sits there still, silent and inscrutable, available for anyone to view online but understood by no one.

What Science Revealed About Its Age

In 2011, researchers at the University of Arizona used radiocarbon dating to confidently date the calfskin pages to the early 15th century, and the ink also dated to the 15th century, making it highly unlikely that the manuscript was a modern forgery. This discovery was crucial. It meant the book wasn’t some elaborate hoax created by Voynich himself to make a fortune.

The results were consistent for all samples tested and indicated a date for the parchment between 1404 and 1438. That’s roughly six centuries ago, during a time when Europe was emerging from the Middle Ages and entering the Renaissance. The dating also demolished one popular theory that had circulated for years.

There was a letter tucked into the manuscript that claimed to identify the author as Roger Bacon, a 13th-century Franciscan friar who had a strong association with magic and secret writing methods. The radiocarbon results proved this theory impossible, placing the manuscript’s creation two hundred years after Bacon’s death.

The Strange Script That Defies All Logic

You might think that with roughly 170,000 characters spread across 240 pages, someone would have cracked the code by now. Here’s the thing, though. Grammatical markers that occur commonly at the beginning or end of words in Indo-European languages never appear in the middle of words in the Voynich manuscript, which is unheard of for any Indo-European, Hungarian, or Finnish language.

Natural languages tend to have an h2 value between 3 and 4, but Voynichese has much more predictable character sequences with an h2 around 2, though at higher levels of organization it displays properties similar to natural languages. It’s almost as if someone deliberately created a writing system designed to look like language while breaking fundamental linguistic rules.

The manuscript has been studied by professional and amateur cryptographers from both World Wars, including codebreakers Prescott Currier, William Friedman, Elizebeth Friedman, and John Tiltman, all of whom were unsuccessful. These were people who broke enemy codes during wartime. If they couldn’t crack it, what hope does anyone else have?

Bizarre Illustrations That Make No Sense

The herbal section contains 126 pages, each displaying one or two plants in a format typical of European herbals of the time, but none of the plants depicted are unambiguously identifiable. They look almost right, almost recognizable, but then you notice impossible details. Leaves growing from roots. Flowers blooming in physically improbable ways. Stems curling into shapes no real plant could maintain.

The astronomical section contains circular diagrams suggestive of astronomy or astrology, with suns, moons, and stars, including one series of 12 diagrams depicting conventional zodiacal constellations. Yet even here, something feels off. The constellations don’t match any known sky from any historical period.

Perhaps most unsettling is what researchers call the biological or balneological section. Naked women swim through fantastical tubes and green baths in illustrations that remain as baffling as they are beautiful. Some scholars suggest these represent alchemical processes, others propose medieval bathing rituals or fertility treatments. Nobody really knows.

Theories That Sound Promising But Lead Nowhere

Over the decades, countless theories have emerged about what the manuscript contains. Some researchers believed it was an encoded medical text. Others argued for an artificial language created centuries before such linguistic experiments became fashionable. Modern handwriting analysis shows that five different scribes worked on the manuscript, leading some to theorize they conspired to create a phony collection of knowledge.

In 2019, Dr. Gerard Cheshire claimed the manuscript was written in Proto-Romance and deciphered it in just two weeks, but the academic community was swift and skeptical, pointing out that Proto-Romance language isn’t a recognized linguistic concept in this context. This pattern repeats constantly. Someone announces they’ve solved it, the media reports it, then experts thoroughly dismantle the claim.

According to Voynich expert René Zandbergen, if you just heard or read that the manuscript has been solved, then rest assured the text has not yet been solved, and one possible explanation is that it might be an elaborate medieval hoax. Maybe there’s nothing to translate at all. Maybe the joke is on everyone who’s ever tried.

Modern Technology Meets Medieval Mystery

You’d think artificial intelligence and machine learning would finally crack this puzzle, right? A 2025 study proposed a historically plausible verbose substitution cipher that can encode Latin and Italian as ciphertext exhibiting many of the manuscript’s statistical properties, though the author stresses it is a proof of concept. In other words, it shows what’s possible but doesn’t prove it’s the actual solution.

Linguists Claire Bowern and Luke Lindemann applied statistical methods comparing it to other languages and encodings, dismissing theories that the manuscript is gibberish and suggesting it’s likely an encoded natural language or constructed language. That’s actually encouraging. It suggests there might genuinely be something to read, if only we could figure out how.

A recent experiment in which volunteers were asked to write pages of gibberish produced texts with similar characteristics to the Voynich Manuscript, including interspersing long words with short words and choosing short words beside illustrations according to available space. This is troubling because it suggests the manuscript could have been created through a simple process of making things up rather than encoding real information.

Why This Book Still Matters Today

Let’s be real here. The Voynich Manuscript might be completely meaningless. It could be an elaborate medieval prank, a failed experiment in language creation, or an alchemist’s fever dream given physical form. Yet something about it continues to fascinate us in 2025.

There’s something about the inscrutable manuscript that sucks you in, as people love a good mystery, and it seems like if you put enough effort into it you could probably decipher it. That’s precisely the trap. The manuscript dangles the possibility of solution just beyond your grasp, making you think that maybe with just a little more time, a little more effort, you’ll be the one to finally understand it.

The manuscript’s plant images resemble those found in alchemical herbals produced in northern Italy during the 15th century, and clues including a tiny sketch of a castle with distinctive swallowtail merlons and a Florentine hat indicate a northern Italian origin. So we know roughly when and where it came from. We just don’t know why it exists or what it says.

The Voynich Manuscript remains undeciphered despite centuries of attempts by top cryptographers and historians, and the expert consensus remains that it is undeciphered. Perhaps that’s okay. Perhaps some mysteries are meant to remain unsolved, reminding us that human knowledge has limits and that the past still holds secrets we may never unlock. What do you think the manuscript really contains? Could it still reveal its secrets, or should we accept that some puzzles from history will forever remain beyond our understanding?