Across parks, sidewalks, and hiking trails, one quiet fault line is widening between dog lovers: the belief that “my dog is friendly” versus the stark reality of serious, sometimes life-changing bites. Veterinarians, behaviorists, and public-health researchers are increasingly warning that certain breeds, especially when poorly trained or unmanaged, can be far more dangerous when roaming free. At the same time, millions of responsible owners feel unfairly judged, insisting that breed alone doesn’t define behavior. Caught in the middle are bystanders, kids on bikes, elderly walkers, and other dogs who have no way to opt out of a bad encounter. This article looks at 13 breeds that science and incident data suggest should almost in public spaces – paired with the deeper question of why control, not blame, is the real solution.

The Hidden Clues: Why Some Breeds Pose Higher Risk Off-Leash

When you see a blocky-headed dog thundering across a field toward you, your brain makes a snap judgment in less than a second – even before you consciously register the breed. Neuroscience research on threat detection shows that humans are wired to overreact to ambiguous danger, especially when it involves fast movement and large size. With dogs, this instinct often collides with a culture that romanticizes “freedom” and “letting dogs be dogs.” But epidemiological studies from hospitals and public health agencies tell a more sobering story: a small subset of breeds, when involved in bites, tend to inflict deeper wounds, more facial injuries, and a higher rate of emergency surgery.

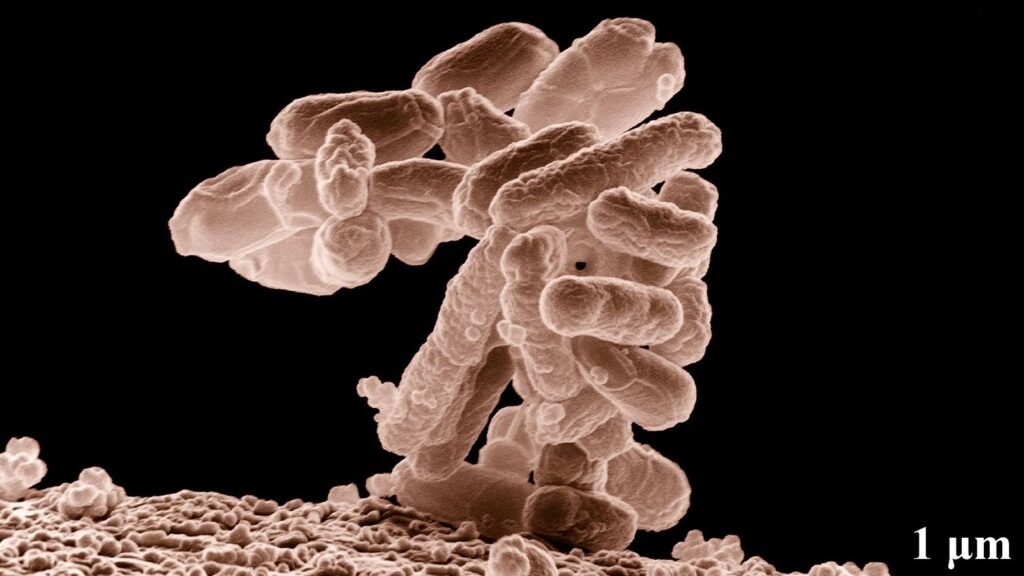

These patterns are not about moral judgment; they’re about force, anatomy, and behavior. Strong jaws, thick neck muscles, and a genetic history of guarding, fighting, or high-intensity work all collide in a split second when a startled or frustrated dog lashes out. Behaviorists talk about “level of arousal” and “bite inhibition” as key risk factors, and both can be compromised when a dog is off-leash, overstimulated, and beyond easy human control. The hidden clue is that risk isn’t only whether a dog might bite; it’s how bad the outcome is likely to be if it does. That’s why, for certain breeds, the leash is less a restriction and more a vital safety device.

Power and Precision: American Pit Bull Terriers and Close Relatives

The American Pit Bull Terrier and related bully-type mixes sit at the center of one of the most heated debates in animal science and public safety. On one hand, many are cherished family companions, socialized from puppyhood and never displaying more than a goofy enthusiasm. On the other hand, hospital records and legal case reviews repeatedly show that when serious attacks occur, bully-type dogs are overrepresented compared with their share of the pet population. The reason is partly mechanical: these dogs tend to have muscular bodies, high pain tolerance, and an explosive acceleration that makes it hard for even experienced owners to intervene quickly.

Complicating things further, breed labels in shelters and veterinary records are often wrong, which muddies the data and fuels arguments on all sides. But one consistent finding across behavior research is that many bully-type dogs show intense “grab and hold” tendencies when they do bite, leading to tearing injuries instead of quick, inhibited snaps. That style of aggression, especially when triggered by frustration or redirected arousal at the end of a chase, can be devastating if the dog is off-leash and unresponsive to recall. Keeping these dogs leashed in public spaces is not an insult to the breed; it is a practical acknowledgment of what can happen if the worst two seconds of a dog’s life collide with a stranger’s bad luck.

Guardians at the Gate: Rottweilers, Dobermans, and Other Protection Dogs

Rottweilers, Dobermans, and similar guardian breeds were literally engineered to make high-stakes decisions about who belongs and who does not. Historically, they guarded livestock, property, and people, responding quickly to perceived threats without waiting for a second opinion. Modern behavior tests still show above-average levels of territorial suspicion and body sensitivity in many individuals, traits that can be perfectly manageable under tight control. Unleashed, however, those same traits can morph into hair-trigger responses to joggers, delivery workers, or even someone lifting an arm too fast.

Each time I interview trainers who work with protection breeds, I hear a version of the same confession: they adore these dogs but treat public outings like handling a loaded tool, not a plush toy. A leash, in this context, is part seat belt and part steering wheel. It keeps the dog from rehearsing “patrolling” behavior around strangers and prevents small misunderstandings – a sudden stare, a flapping coat – from turning into a bite incident. For large guardians whose bite force and commitment can cause extensive damage, staying on-leash in public is less about distrust and more about responsible respect for what the dog was bred to do.

From Livestock Fields to City Streets: German Shepherds, Malinois, and Herding Breeds

German Shepherds, Belgian Malinois, and some other herding breeds sit in a strange space between family pet and tactical tool. They are favored by police and military units precisely because they can switch from calm observation to intense action in a heartbeat. That same trait can spell trouble when a bored, under-trained shepherd is allowed to roam off-leash in urban or suburban settings. Studies of working-dog selection highlight traits like high prey drive, relentless focus, and willingness to engage physically with a “target” – all superb in a controlled job, but risky when pointed at random cyclists or unfamiliar dogs.

When these breeds become frustrated – say, when they can see movement but cannot get to it – many display what behaviorists call barrier frustration or redirected aggression. Off-leash, there is often no barrier, only a straight-line path between the dog and a perceived problem. I once watched a Malinois on a hiking trail “herd” a group of kids downhill, nipping heels just hard enough to draw shrieks and tears; the owner called it playful, but the fear on those faces told a different story. For high-drive herders, a leash acts as a boundary between instinct and inappropriate outlet, protecting both the public and the dogs themselves from situations that could end their freedom permanently.

Why It Matters: Small Numbers, Outsized Consequences

At first glance, insisting that certain breeds stay leashed can sound like superstition or breed bias, especially in a country overflowing with loving dog stories. But public-health data tell a harder truth: a relatively small fraction of dogs are responsible for a disproportionately large share of severe bite injuries, reconstructive surgeries, and fatalities. Children, especially those under the age of ten, absorb much of this harm, often to the face, neck, and hands. Traditional advice like “ask before you pet” and “stand still like a tree” puts all the responsibility on the victim, not on the animal and handler.

Why this matters scientifically is that we now know bites are not random accidents; they arise from a predictable collision of genetics, environment, and human choices. Leash laws and breed-specific restrictions have been blunt tools, often poorly enforced and emotionally charged. A more precise approach looks at individual behavior and context, while still openly acknowledging that some breeds pose greater risks if things go wrong. It is uncomfortable to say that a single off-leash incident from a powerful dog can have the same medical impact as dozens of nips from smaller breeds – but that mismatch is exactly what emergency physicians confront. Recognizing this imbalance is the first step toward policies and personal habits that prevent trauma instead of merely reacting to it.

Global Perspectives: Cane Corsos, Presa Canarios, Kangals, and Other Heavyweights

Outside the familiar list of shepherds, pit bulls, and Rottweilers lies a growing category of massive guardian breeds: Cane Corsos, Presa Canarios, Dogo Argentinos, Kangals, and similar dogs that once patrolled farms, estates, and rugged borderlands. Many of these breeds were shaped to confront wolves, human intruders, or large predators, combining enormous strength with territorial aggression. As they gain popularity in urban environments and online as status symbols, behavior specialists are sounding quiet alarms. These are not generic “big dogs”; they are power athletes with deep genetic programming for confrontation.

When countries in Europe and South America have reviewed serious dog attacks, some of these breeds appear frequently enough to spark targeted legislation or mandatory controls. Off-leash, their sheer size makes any conflict – whether with another dog or a human – dangerous from the first second. Even a single lunge can knock down an adult or yank an owner off their feet, eliminating any chance of quickly regaining control. For these heavyweights, an on-leash rule in public is less about paranoia and more about acknowledging that, if something does go wrong, there are no minor mistakes.

Myths, Mislabels, and the Science of Aggression

One of the most persistent myths in the dog world is that aggression is entirely about how an animal is raised. While early socialization and humane training are incredibly powerful, genetic studies over the last decade have shown that behavior traits – including fearfulness, reactivity, and some forms of aggression – are heritable to a meaningful degree. That does not mean any individual dog is “destined” to be dangerous, but it does mean certain lines and breeds are more likely to express intense responses under stress. When those traits are layered onto strong, athletic bodies, the risk profile changes dramatically.

Labels can mislead in both directions. Some so-called “dangerous” breeds are gentle couch potatoes, while many small dogs are chronically undertrained serial biters whose injuries simply do not send people to the hospital as often. Scientists studying dog aggression emphasize looking at patterns, not anecdotes. They point out that the absence of bites does not mean the absence of risk; it may simply reflect limited exposure or pure luck so far. For powerful breeds, staying on-leash in public is a way to prevent that first serious incident from ever happening, instead of betting on a lifetime of perfect circumstances.

The Future Landscape: Tech, Training, and Rethinking Responsibility

Looking ahead, the debate over aggressive dogs and leash use is likely to intersect with new technologies and shifting legal norms. Wearable sensors and GPS trackers are already helping some owners monitor their dogs’ heart rates, stress levels, and locations in real time, offering a glimpse into invisible states of overarousal before they boil over. At the same time, courts and insurers are increasingly willing to treat preventable dog attacks as failures of due diligence, not just accidents. Some cities are experimenting with tiered licensing systems, where owners of high-risk breeds must complete behavior classes or pass temperament assessments to access off-leash spaces.

There is also a growing ethical conversation inside the training community about what it really means to give a dog a good life. Is freedom to run unsupervised in a crowded park more important than the psychological safety of people and other animals who share that space? Many behaviorists argue that long lines, fenced fields, and structured play are better outlets for high-risk breeds than fully off-leash mingling. If these ideas gain traction, we may see a future where “responsible ownership” for powerful dogs always includes a leash in public, much like seat belts became a non-negotiable part of driving. In that landscape, aggression risk becomes something we actively manage, not something we apologize for after the fact.

From Fear to Action: What Dog Owners and Bystanders Can Do

For all the statistics and heated arguments, the most meaningful changes often start with small, personal choices. If you own one of the breeds discussed here – or any large, strong dog – committing to consistent on-leash walks in public spaces is an immediate, concrete step. Pair that with early socialization, force-free training, and careful management around children and unfamiliar dogs, and you dramatically cut the chance of a nightmare scenario. Simple habits, like crossing the street to avoid tight encounters or calling out “we’ll give you space,” can defuse tension before it escalates.

For people without dogs, there are ways to engage constructively rather than just feeling afraid. Learning basic dog body language, supporting evidence-based leash laws, and backing community access to low-cost training and behavior help can all move the needle. When someone insists their powerful dog “doesn’t need a leash,” pushing back politely but firmly – especially in shared spaces – can reinforce a culture where safety comes first. In the end, the question is not whether these 13 breeds are good or bad; it is whether we are willing to handle them in ways that respect both their abilities and other people’s right to feel safe. Given what you now know, how will you react the next time you see a large off-leash dog heading your way?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.