Imagine waking up beneath a sky that never blazes blue, lit instead by a dim, coppery star that hangs low and sullen, more ember than flame. For decades, astronomers have wondered not just about distant red dwarf systems, but about what our own world would look like under such a star. Now, with better models of stellar evolution and exoplanet climates, that thought experiment has become a serious scientific puzzle with surprisingly human stakes. A shrunken, cooler Sun could mean everything from frozen oceans to radically reshaped calendars to a completely different story about how long life can last here. The mystery is simple to pose and much harder to solve: if our Sun had been born a red dwarf instead of a yellow star, would Earth ever have had a chance?

The Hidden Clues in Our Own Sun

One of the strangest twists in this story is that we only understand red dwarfs because we studied stars like our own first. The Sun, technically a G‑type main sequence star, acts as the baseline against which astronomers measure everything else. By tracking how its light changes, how fast it spins, and how it burns hydrogen in its core, researchers have learned to rewind and fast‑forward stellar lives in computer models. Those same models show that red dwarfs are the minimalists of the cosmos, burning cooler and slower, stretching their lifetimes to trillions of years. In other words, if our Sun had been a red dwarf, the clock for life in our solar system would tick unimaginably longer.

But longevity has a price. Our Sun’s brightness has increased gradually over billions of years, warming Earth from a colder early phase into a relatively stable, habitable climate. A red dwarf, by contrast, would start far dimmer, forcing any habitable planet to huddle much closer. That tight orbit would reshape everything from seasons to tides, turning our predictable solar system into something stranger, more precarious, and far more dramatic than the one we grew up modeling in school.

A Dimmer Star, A Different Earth

To picture Earth under a red dwarf Sun, you first have to shrink the whole orbital layout inward like tightening the strings on a mobile. Because red dwarfs are much cooler, a planet would need to orbit perhaps ten to twenty times closer than Earth does now to receive a similar amount of energy. At that range, our familiar year would collapse into something more like a month‑long loop, with the planet racing around its star in a feverish sprint. Days and nights, if the planet rotated freely, would still come and go, but the sky would never blaze with the harsh white light we know today, only with a deeper, reddish glow. Shadows would lengthen, colors would shift, and photosynthesis might favor different pigments, painting forests in darker, stranger greens – or even purples.

Yet climate would not be guaranteed. Put Earth at the wrong distance from a red dwarf and the oceans would freeze solid, locking water into thick global ice sheets. Bring it too close and a runaway greenhouse could boil the seas. The so‑called habitable zone around a red dwarf is narrow, more like a thin ring than the broad shell we enjoy around our Sun. The margin for error shrinks dramatically, and with it the comfortable sense that a planet can wobble through eons of change and still keep its footing.

Flares, Shadows, and a Sky That Never Sleeps

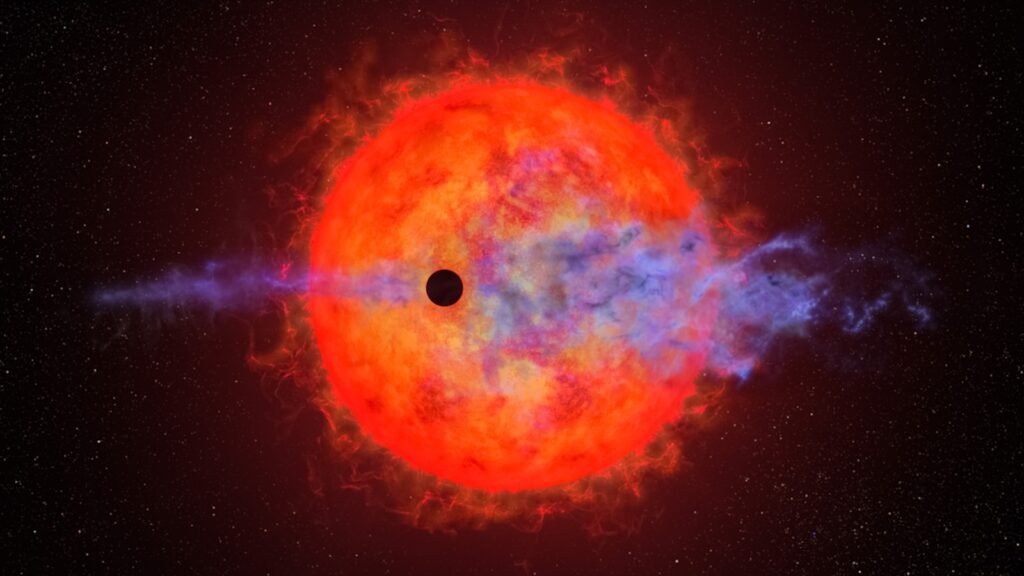

The romantic image of a gentle, ember‑like red dwarf hides a harsher reality: many of these stars are restless, violent, and capricious. Particularly when young, red dwarfs can unleash intense stellar flares, bursts of radiation that make our Sun’s most dramatic storms look almost polite. For a planet huddled close in, that radiation can be punishing, stripping atmospheres and hammering any unprotected surface with charged particles. Under a red dwarf Sun, Earth’s magnetic field would become less of a nice‑to‑have and more of a planetary shield in a constant war. Without a strong magnetosphere, our air and oceans could be slowly peeled away into space.

At the same time, because the habitable zone around a red dwarf is so close, many planets are expected to become tidally locked. That means one hemisphere would face the star in perpetual day while the other lies under permanent night, like a coin frozen mid‑flip. On a tidally locked Earth, one side might broil beneath steady, ruddy light while the far side becomes a deep‑freeze desert. The most habitable regions might be narrow twilight bands circling the planet, where wind and ocean currents could smear out the temperature extremes. Human civilizations, if they ever arose, would live in a world where sunrise and sunset were not daily events, but fixed directions on the horizon.

From Exoplanet Mysteries to a Reimagined Home

The reason astronomers care so much about this alternate‑Sun puzzle has less to do with fantasy and more to do with what telescopes are actually seeing. The vast majority of stars in our galaxy are red dwarfs, and many of the most promising exoplanets discovered so far orbit them. When scientists study worlds like Proxima Centauri b or the TRAPPIST‑1 system, they are effectively exploring versions of this what‑if scenario, just played out light‑years away. Every time a telescope captures a tiny dip in a red dwarf’s light – evidence of a planet passing in front – it adds a new clue to the question of how habitable red dwarf systems truly are. Our thought experiment about a red dwarf Sun is suddenly not theoretical at all; it is a training ground for interpreting real data.

Those data have already turned up surprises. Some red dwarf planets appear dense and rocky, with atmospheres that might survive despite the flares. Others show indications that they could be water‑rich, hinting at oceans under red skies. By flipping the script and imagining Earth in those conditions, researchers can test climate models, runaway greenhouse scenarios, and atmospheric escape physics with more nuance. It is a bit like archaeologists using a single shard of pottery to reconstruct an entire lost culture – except here, the shard is a brief change in starlight, and the culture is an alien climate we may never visit in person.

Why It Matters: The Human Stakes of a Smaller Sun

On the surface, asking what would happen if the Sun were a red dwarf sounds like late‑night dorm talk. But the implications cut to the core of how we think about life’s odds in the universe and our own long‑term future. A red dwarf solar system would probably give life more time to evolve, because these stars burn so slowly that they barely age on human or even geological timescales. Our real Sun will swell into a red giant and sterilize the inner solar system roughly several billion years from now; a red dwarf equivalent may still be quietly fusing hydrogen when our star is long dead dust. That means that in a galaxy dominated by red dwarfs, most habitable worlds could be much older and more enduring than Earth.

There is also a sobering counterpoint. The same stellar flares and tidal locking that challenge red dwarf planets raise the possibility that many of them are barren or only marginally habitable. If that is true, then our relatively stable, mid‑life Sun might be an unusually kind host, not the cosmic average. In that case, our civilization sits on a rare perch: orbiting a star that is bright enough to keep climates dynamic, yet gentle enough to allow complex life to flourish for billions of years. Whether red dwarfs are friendly or hostile to life will shape the way we interpret every new exoplanet headline for decades to come, and, by extension, how alone – or not – we believe ourselves to be.

Global Perspectives: Calendars, Cultures, and Civilizations Under a Red Dwarf

If you shift the Sun, you do not just change the physics; you rewrite the entire human story. Under a red dwarf Sun, with a year that might last a few weeks and a permanent twilight region girdling the globe, our calendars would not look anything like the ones hanging in kitchens today. Seasonal festivals might be tied not to the tilt of the planet, but to slow oscillations in the star’s activity or long‑term climate cycles. Coastal cultures would be shaped by extreme tides driven by the close orbit and perhaps more massive moons, turning some shorelines into ever‑changing frontiers. Navigation, agriculture, and even mythology would evolve around a sky that glows a deeper red and never quite reaches the Sun‑at‑noon brilliance we take for granted.

There is a more intimate psychological angle, too. Humans respond strongly to light and color; our sleep cycles, moods, and health are tuned to the spectrum of our current Sun. A redder sky and dimmer days would tug at those rhythms, potentially pushing evolution in subtle directions. Vision might favor lower‑light sensitivity over sharp color discrimination. Architecture could emphasize capturing and concentrating precious sunlight, with cities built like giant flowers following the star. When exoplanet researchers imagine civilizations under red dwarfs, they are not just mapping out temperatures and pressures; they are sketching futures where entire cultures bloom under a different shade of starlight.

From Ancient Speculation to Modern Stellar Science

Humans have been reimagining the Sun for as long as there have been myths, painting it as a chariot, a god, a watchful eye. The scientific twist came only in the last few centuries, when spectroscopy and physics revealed that the Sun is one of many stars, not a special kind of fire. Once astronomers recognized that stars come in families – blue giants, yellow dwarfs, red dwarfs – it was only a matter of time before someone asked what kind of worlds each family might host. Red dwarfs, initially dismissed as too faint and uninteresting, have surged to the forefront of research as instruments became sensitive enough to detect small planets around them. What began as abstract classification has turned into a detective story, with each new system hinting at different planetary fates.

In that sense, wondering about a red dwarf Sun is part of a long tradition: using imagination anchored by data to push science forward. Just as early planetary scientists once debated what Venus or Mars might be like before spacecraft arrived, today’s astronomers work with incomplete, sometimes frustratingly thin evidence. They run climate models, plug in different stellar spectra, and watch virtual Earths freeze, boil, or find a fragile balance. The payoff is not only a better understanding of distant worlds, but a renewed appreciation of how finely tuned our own circumstances are. Our yellow star, in this broader cosmic census, is neither the loudest nor the quietest voice in the choir – but it may be one of the most forgiving.

The Future Landscape: Telescopes, Technologies, and Long-Term Possibilities

The next few decades will either vindicate or upend many of the assumptions baked into our red dwarf what‑if scenario. New space telescopes and advanced ground‑based observatories are edging closer to reading the atmospheres of Earth‑sized planets around nearby stars. By analyzing how starlight filters through those atmospheres during transits, scientists hope to identify signatures of water vapor, carbon dioxide, or even gases associated with biological activity. Red dwarfs, being small and dim, actually make these subtle signals easier to detect, which means they are at the front of the line for atmospheric characterization. Our computer‑modeled red‑Sun Earth will gain or lose credibility with every new spectrum collected.

Looking even further ahead, some thinkers stretch the thought experiment into the far future of our species. If humanity or its descendants survive long enough to see the Sun leave the main sequence billions of years from now, they may look to red dwarfs as potential refuges. These stars, with their immense lifespans, could host artificial habitats, engineered planets, or vast space‑borne ecosystems basking in gentle, eternal twilight. Of course, that vision faces daunting technological and ethical hurdles long before it could become reality. Still, the mere fact that red dwarfs offer such enormous time horizons changes how we think about the ultimate timeline of life in the cosmos – and our own place on it.

Why You Should Care: A Call to Curiosity and Action

So why should a busy person living under a very non‑red Sun in the year 2025 care about any of this? Because the question of a red dwarf Sun is really a question about how fragile and special our own circumstances might be. Supporting the science that probes these ideas – through public funding, science education, and even individual attention to new discoveries – helps sharpen our picture of the universe and our odds within it. Simple actions, like visiting a local planetarium, backing citizen‑science projects that classify exoplanet data, or encouraging curiosity in kids, all feed into a culture that values deep, patient questions. The more we learn about stars that are not like ours, the better we understand the one we depend on every second of our lives.

There is also a quiet, personal payoff in sitting with this kind of cosmic what‑if. When you realize that most stars are cooler and dimmer than the Sun, and that countless planets whirl in cramped, tidally locked orbits under red skies, our own blue‑and‑gold daylight starts to feel like a rare gift. That awareness can shift how we think about everything from climate change to long‑term planning; it reminds us that there is no spare Earth waiting just a few light‑minutes away. Engaging with these questions is a way of grounding ourselves, not escaping. The Sun we have is not a red dwarf, and that fact has written the entire script of life on this planet.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.