Have you ever wondered how advanced our ancestors really were? While we often picture ancient civilizations as primitive societies struggling with basic tools, the reality is far more fascinating. Scattered across the globe lie remnants of technologies so sophisticated that they wouldn’t be replicated or understood until centuries later. From self-healing concrete to ancient computers capable of predicting eclipses, these innovations reveal that human ingenuity has deeper roots than we imagined.

Honestly, some of these discoveries are so impressive they almost seem like science fiction. Yet they’re real, tangible proof that ancient minds were capable of extraordinary feats. Let’s explore eight remarkable technologies that prove our ancestors were far more advanced than history books often give them credit for.

Damascus Steel: The Mystery Metal That Contained Nanotechnology

Picture a sword so sharp it could slice through silk scarves dropped onto its blade, yet so flexible it could bend without breaking. Damascus steel blades were claimed to be able to cleanly slice through a falling silk scarf, leaving European warriors astounded by their capabilities. This steel was among the finest in the world and was the metal used to fashion weapons such as the famous Damascus blades of the Middle Ages.

What made this steel truly extraordinary wasn’t just its performance, but what scientists discovered when they examined it centuries later. This steel contained microscopic carbon nanotubes – a technology we only “discovered” in the 20th century. Damascus steel was first produced in India from iron ore with high carbon content and additional trace elements, then the ingots were sent to Damascus, Syria, where they were made into swords with beautiful surface patterns and superior physical ability.

The most remarkable aspect is how the technology was lost. The technique wasn’t lost due to forgotten knowledge, but rather because the composition of the material changed – the swordsmiths got their steel ingots from India, but in the 19th century the mining region changed, and the new ingots had different impurities that couldn’t be forged into Damascus steel. It was only during the 20th century, after decades of experimentation, that the science behind the production of Wootz steel was understood, proving that ancient Indian metallurgists were technologically way ahead of their time.

The Antikythera Mechanism: Ancient Greece’s Bronze Computer

Found in a shipwreck off the Greek coast, the Antikythera Mechanism is essentially an ancient computer that predicted eclipses, tracked planetary movements, and calculated Olympic Games schedules, dating to around 100 BCE with gear systems so sophisticated that similar technology didn’t appear again until astronomical clocks of the 14th century. Think of it this way: discovering this device is like finding a smartphone in a medieval castle.

The device is unique among discoveries from its time and single-handedly rewrites our knowledge of ancient Greek technology – before its discovery, ancient Greek gears were thought to be restricted to crude wheels in windmills and water mills, but the Antikythera mechanism has precision gears bearing teeth about a millimeter long, completely unlike anything else from the ancient world. The mechanism had the first known set of scientific dials and contained 30 gear wheels, with no other geared mechanism of such complexity known from the ancient world until medieval cathedral clocks were built a millennium later.

The Antikythera mechanism is an ancient Greek hand-powered orrery that was used to predict celestial locations and eclipses decades in advance, and is widely considered the oldest example of an analog computer ever found in the world. Why did it take centuries for scientists to reinvent anything as sophisticated as the Antikythera device? We have strong reasons to believe this object can’t have been the only model of its kind, but bronze was very valuable, and when objects like this stopped working, they would have been melted down for their materials.

Roman Concrete: The Self-Healing Wonder Material

While our concrete crumbles after just 50 to 100 years, Roman structures like the Pantheon have stood firm for nearly 2,000 years because Romans mixed volcanic ash into their concrete, creating a chemical reaction that continues healing cracks over time. Think of it like a living material that repairs itself, something we’re still trying to replicate in our labs today – the Romans somehow stumbled upon a self-healing concrete formula that modern engineers are desperately trying to reverse-engineer.

Recent research has revealed that Roman concrete was even more advanced than we thought, showing that the incorporation of mixtures of different types of lime forming conglomerate “clasts” allowed the concrete to self-repair cracks – they essentially created self-healing concrete 2,000 years ago. It is suggested that once the nature of Roman concrete is understood, it could completely revolutionize modern construction, but even so, scientists have never been able to fully reproduce it, and its mystery remains.

The Romans weren’t just lucky with their concrete recipe. Roman concrete was a mix of volcanic ash, lime, and seawater, which chemically reacted to create an exceptionally durable material that actually gets stronger when exposed to water, unlike modern concrete which weakens – the exact chemical processes that made Roman concrete so resilient remain a mystery. What makes this even more impressive is that they achieved this level of material science without understanding the underlying chemistry.

Ancient Chinese Deep Drilling: Reaching Into the Earth’s Depths

Long before Europeans even dreamed of drilling deep holes, the Chinese were already extracting natural gas from depths that would make modern engineers jealous – they tapped deposits of gas through boreholes up to approximately 2,000 feet deep and routed it through pipes made of bamboo, with ancient engineers in Sichuan province starting this incredible technology around 2,000 years ago. Salt was essential in antiquity for preserving food, so around 2,000 years ago, the Chinese developed advanced drilling technology to extract salt directly from underground deposits using a bamboo drill with a heavy, rhythmically pounding drum capable of reaching depths of up to 600 meters.

Sometimes during drilling, they encountered methane pockets and eventually learned how to harness that gas too – it’s an astonishing example of technological ingenuity far ahead of its time. Ancient China’s development of deep drilling techniques predates similar advancements in the West by hundreds of years. What’s particularly remarkable is how they managed to achieve such precision with bamboo tools and percussion drilling methods.

The sophistication of their drilling operations went beyond simple salt extraction. They developed complex systems for managing groundwater, preventing cave-ins, and handling dangerous gases. Their bamboo pipeline networks could transport natural gas across considerable distances, creating an early industrial infrastructure that wouldn’t be matched in the West until much later periods.

The Baghdad Battery: Ancient Electrical Power

The Baghdad Battery is a clay pot which encapsulates a copper cylinder with an iron rod suspended in the center but not touching it, both held in place with an asphalt plug – these artifacts were discovered during 1936 excavations near Baghdad in Iraq from a village about 2,000 years old built during the Parthian period between 250BC and 224 AD. When filled with a mild acid, such as vinegar, this assembly generates approximately 1-2 volts of electricity.

The Baghdad Battery is essentially an ancient battery, albeit a primitive one – acidic liquid inside the jar likely triggered an electron flow from one metal to the other, just like in today’s batteries. But what was it used for? That remains a mystery, with theories ranging from electroplating metals to religious rituals involving electric shocks to awe or punish the unfaithful.

Keyser proposes that since electric fish are not found in the Persian Gulf or Mesopotamian rivers, ancient peoples may have created the Baghdad Battery as an alternative means to harness electricity – this theory offers a new perspective on ancient technological innovation. Even though the electric battery was not invented until 1799 by Alessandro Volta, the iron rods that were inside these cylinders were supposedly destroyed by some acid, suggesting they were some form of prehistoric battery.

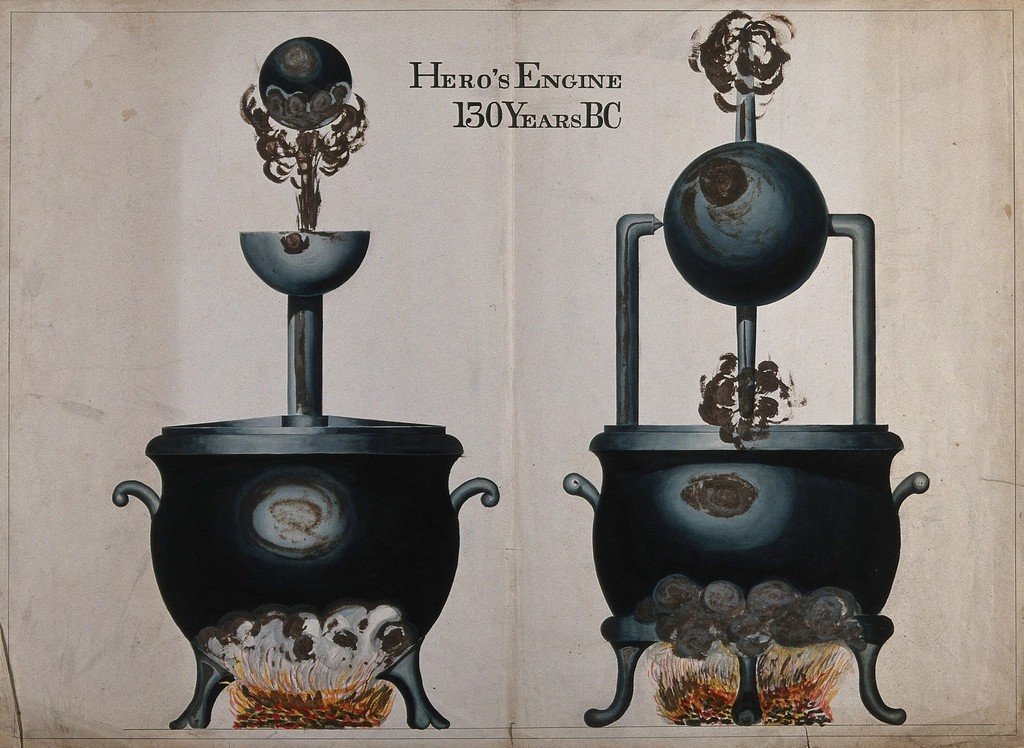

Hero’s Steam Engine: Power Before the Industrial Revolution

What very few people know is that Hero of Alexandria was the first inventor of the steam engine, a steam powered device called aeolipile or the ‘Heron engine,’ with the name coming from the Greek word ‘Aiolos’ who was the Greek God of the winds. Nearly 1,800 years before the start of the Industrial Revolution, Hero created the world’s first steam engine called the aeolipile.

The aeolipile is considered to be the first recorded steam engine or reaction steam turbine, but it is neither a practical source of power nor a direct predecessor of the type of steam engine invented during the Industrial Revolution. While a cool device to show all your Ancient Greek buddies, it had little in the way of actual use – Heron’s device is inherently the wrong design to produce much in the way of useable power.

Hero’s aeolipile was more an interesting curio than an actual machine for work, but we need to keep in mind how far ahead of its time this machine was – once forgotten, we don’t know of any other person inventing a steam engine until the Ottoman inventor Taqi al-Din in 1577, and he was considered the greatest scientist on Earth by his contemporaries. Hero created his steam engine well before the Industrial Revolution of the 1700s and 1800s, meaning the Ancient Greeks were capable of advanced mathematical, scientific, and mechanical thought that enabled them to see the world differently and understand that theories provided the foundation to create wonderful devices.

The Lycurgus Cup: Roman Nanotechnology in Glass

The Lycurgus Cup appears jade green when lit from the front, but changes color to a rich blood red when lit from behind – this unusual and extremely modern property for that era has amazed scientists for decades. Scientists solved the mystery of the ancient mechanism behind the cup by examining the glass under a microscope and discovering that Roman artisans had impregnated it with particles of silver and gold that were smaller than one thousandth of a grain of table salt – researcher Ian Freestone from University College London called this painstaking work “an amazing feat”.

This color-changing magic is actually ancient nanotechnology – the glass contains tiny particles of gold and silver scattered at the nanoscale that interact with light in a way that baffles many modern materials scientists, showing that Romans had an intuitive grasp of chemistry and optics even if the science was unknown to them. This dichroic glass contains gold and silver nanoparticles that were incorporated during production, achieving what we now call nanotechnology by manipulating matter at the atomic level – modern scientists only figured out how this worked in the 1990s using electron microscopes, representing a level of materials science that wouldn’t be matched again until the 20th century.

The precision required to create such effects is staggering. The Romans had to control particle size, distribution, and suspension in molten glass with incredible accuracy. They achieved this without any understanding of atomic structure or light wavelength theory, relying purely on empirical experimentation and artistic intuition.

Ulfberht Swords: Viking Super Steel

Between 800 and 1000 CE, Viking warriors wielded swords marked with “+ULFBERHT+” that were made from crucible steel so pure it wouldn’t be matched in Europe until the Industrial Revolution – these swords contained steel with a carbon content that required furnace temperatures of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, far beyond what medieval technology should have achieved. These weapons represent one of history’s most puzzling metallurgical achievements.

The Ulfberht swords contained steel that was remarkably pure and consistent, with a carbon content perfectly balanced for creating flexible yet incredibly sharp blades. The Vikings somehow obtained or developed techniques for creating steel that European smiths couldn’t replicate for centuries. The mystery deepens when we consider that the Vikings weren’t known primarily as metallurgists, yet they possessed some of the finest steel technology of their era.

What makes these swords even more intriguing is their sudden appearance and disappearance from the archaeological record. The technology seems to have emerged fully formed and then vanished just as mysteriously. Some researchers suggest the Vikings may have acquired the steel through trade with more advanced metallurgical centers, while others propose they developed unique smelting techniques that were later lost.

Conclusion

These eight remarkable technologies shatter our assumptions about ancient capabilities and prove that innovation isn’t a modern monopoly. From Damascus steel’s accidental nanotechnology to Hero’s steam-powered curiosities, our ancestors achieved feats that seem almost impossible given their supposed technological limitations. These ancient innovations remind us that humanity’s inventive spirit has deep roots – from steam power to chemical warfare and electricity, our ancestors were thinking ahead, often much further than we give them credit for.

What fascinates me most is how many of these technologies were lost and had to be rediscovered centuries later. It makes you wonder what other innovations might be buried in archaeological sites, waiting to surprise us. The next time you use your smartphone or drive your car, remember that the spark of human ingenuity that created them burns just as brightly as it did in ancient Damascus workshops or Greek laboratories thousands of years ago. What do you think about these incredible ancient achievements? Share your thoughts in the comments below.