In a world of sirens, sensors, and smartphone alerts, a quiet question lingers at the edges of science: can people feel an earthquake coming before machines call it? The idea is seductive, fueled by stories of sudden unease, pressure in the ears, or an uncanny urge to move just seconds before the floor ripples. Seismology, grounded in rigorous measurement, remains skeptical, yet the human body is a remarkably sensitive instrument in its own right. This is a story about thresholds – between myth and mechanism, instinct and instrumentation – and what we actually know in 2025.

The Hidden Clues

Could your inner ear feel an earthquake before your brain knows what it is? When a fault slips, the first whisper is a fast, faint primary wave that nudges structures and bodies alike before the more damaging secondary waves roll in. People sometimes register that nudge as a wobble or sudden disorientation, a blink of confusion that feels like a trick of the room rather than geology in motion. On assignment in Los Angeles, I once felt that barely-there sway and hesitated, half-ready to blame coffee, until the official alert lit my phone – and then the stronger shaking arrived. That sequence matters because it undercuts the idea of paranormal foresight while still giving the body credit for real-time sensitivity.

The brain is a prediction engine, and when the senses deliver ambiguous signals, it fills gaps fast. In quake country, that can turn everyday vibrations – traffic, a slamming door – into false positives, and it can also sharpen attention to genuine micro-motions. The space between those two outcomes is exactly where this mystery lives.

From Ancient Signs to Modern Science

Long before seismometers, communities watched animals, wells, and the sky for hints of upheaval, weaving patterns from experience and fear. Folklore recorded unusual behaviors, odd lights near horizons, and changes in water clarity as harbingers, none of which rose to the standard of testable prediction. Modern seismology emerged in the late nineteenth century with instruments that track ground motion so precisely they routinely outpace human reaction. Today’s early warning systems detect those first, weaker waves and broadcast alerts that can arrive a few to tens of seconds before stronger shaking, a window that saves lives and slows trains.

Smartphone-based networks add another layer by turning many devices into a sprawling sensor array. The point is simple: instruments do not just beat us on speed; they also scale, coordinating thousands of eyes and ears that never blink. That doesn’t make human perception irrelevant – it just reframes it.

The Physiology Question

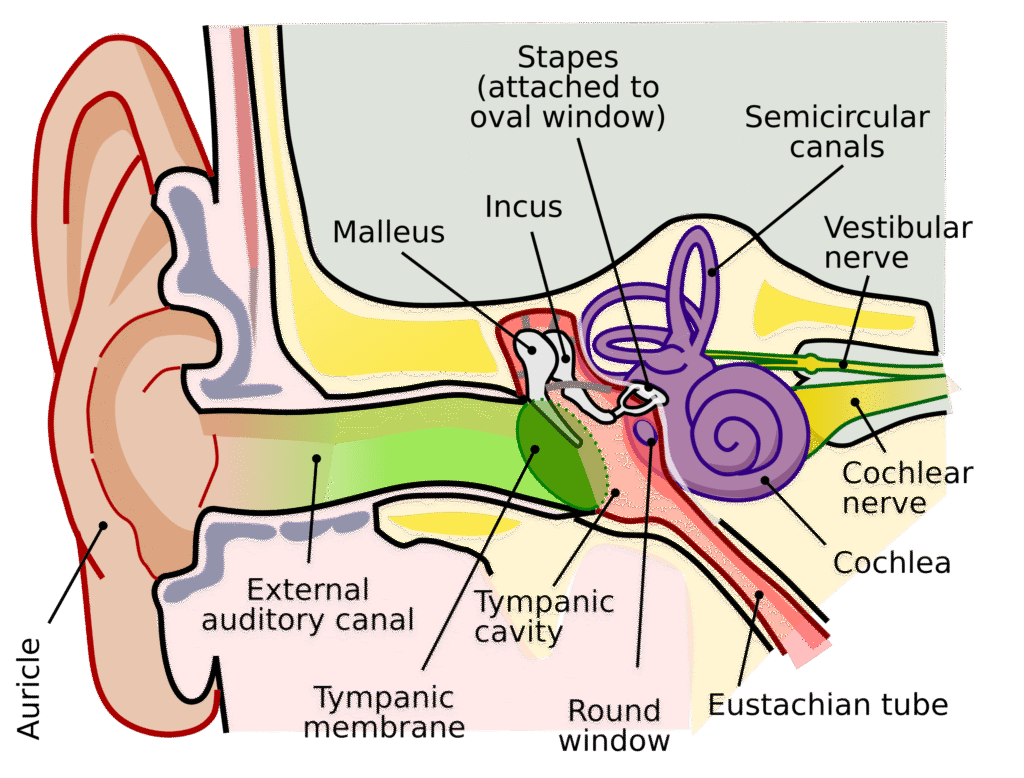

The human vestibular system, tucked in the inner ear, excels at sensing slow tilts and gentle accelerations, the very kinds of motions that small seismic waves can produce. For some people, that translates into a momentary feeling of imbalance, a subtle sideways drift, or a sudden stillness as the brain tries to reconcile competing signals. Others report ear fullness or a pressure shift, sensations consistent with low-frequency motion or infrasound brushing past normal awareness. None of this requires exotic biology; it is the same machinery that keeps us upright on a rocking boat, reacting to tiny changes before we consciously decide how to stand.

Where the evidence thins is in claims that people detect earthquakes minutes to days ahead through electromagnetic sensitivity or chemical smells. Lab studies have probed whether stressed rocks emit signals that might nudge human physiology, but so far, results do not reach operational reliability. The more we look, the more the plausible window collapses to seconds – and that aligns with the physics of seismic wave travel.

What the Data Actually Shows

Carefully documented cases fold into a common pattern: people sometimes notice the earliest, gentlest motions from primary waves and interpret them only after the stronger waves arrive. Reports collected after major earthquakes often show a wide spread of experiences, from clear early sensations to none at all, reflecting both biological variation and memory bias. When researchers compare those reports with instrument timelines, the human signals cluster tightly around the first-arriving waves, not earlier anomalies. That is not nothing; it is the body functioning as a near-instant sensor with a narrow and variable threshold.

Crucially, when the goal shifts from explanation to prediction, false alarms explode. Day-to-day vibrations, stress, and expectation can mimic the same internal cues that a real P-wave produces. Without a clock-synced network and ground-truth data, personal sensations alone tell an incomplete – and often misleading – story.

Why It Matters

Early action is the currency of safety in earthquakes, and even a few seconds can mean automatic shutoffs, surgical pauses, and kids ducking under desks. If human bodies did provide reliable advance warnings, it would change the way public alerts are designed, potentially blending subjective signals with sensor data. But the bar for reliability is high, because missed events and false alarms have costs of their own – panic, complacency, and fractured trust. That is why operational systems prioritize hard thresholds from calibrated instruments, not gut feelings, however compelling they may seem.

There is still a role for experience. When people recognize the sensation of an early nudge, they can act faster without waiting for an alert, closing the behavior gap that often eats precious seconds. Understanding the limits of perception clarifies, rather than competes with, what machines do best.

Global Perspectives

Japan’s nationwide early warning, Mexico’s siren network, and expanding systems in the United States and elsewhere show how societies translate wave physics into public action. In these places, alerts sometimes arrive before anyone consciously notices motion, sometimes during the first faint wobble, and sometimes not at all when the epicenter is close and seconds are scarce. Communities also participate through voluntary reporting – submissions that map shaking intensity and help scientists validate models in near real time. Those reports are valuable precisely because they are anchored to the instrument-recorded event, not used as predictors.

Culture shapes expectations, too. In regions with long earthquake memories, people practice protective actions until they become reflex, narrowing the time between perception and response. Elsewhere, where earthquakes are rare, that reflex can be slower, and the same faint nudge may be dismissed until the bookshelf rattles. Training, not telepathy, explains much of the difference.

The Future Landscape

The next frontier is density: more sensors in more places, and new kinds of sensors altogether. Fiber-optic cables that span cities and seafloors can double as continuous motion detectors, turning existing infrastructure into vast, always-on seismographs. High-rate satellite positioning helps estimate the size of very large earthquakes quickly, complementing the initial wave detections that set alerts in motion. Machine-learning tools are getting better at filtering noise and teasing out signals, not to replace physics, but to sharpen it under messy real-world conditions.

On the human side, wearables that track motion and heart rate could eventually document how bodies respond during the earliest moments of shaking, offering insights into perception thresholds and stress responses. The challenge will be privacy, consent, and making sure that such data refines, rather than confuses, the decision pipeline. The win is clear: faster, smarter alerts that give more people a chance to act.

How You Can Engage

Enable earthquake alerts on your phone and learn the protective mantra – drop, cover, and hold on – so your body moves before your brain has time to argue. Secure heavy furniture, store a flashlight and sturdy shoes near your bed, and plan family check-ins that do not depend on congested cell networks. If you live in a quake-prone region, practice short, regular drills so that a faint wobble becomes a useful cue rather than a split-second of doubt. Consider participating in community programs that collect felt reports, which help scientists map shaking and refine hazard models after events.

Stay curious but skeptical about claims of long-term prediction based on human sensations alone. The best path forward blends human awareness with instrument precision, turning both into layers of safety rather than competing stories. In the meantime, a prepared mind – and a few smart settings on your devices – can be the difference between surprise and swift action.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.