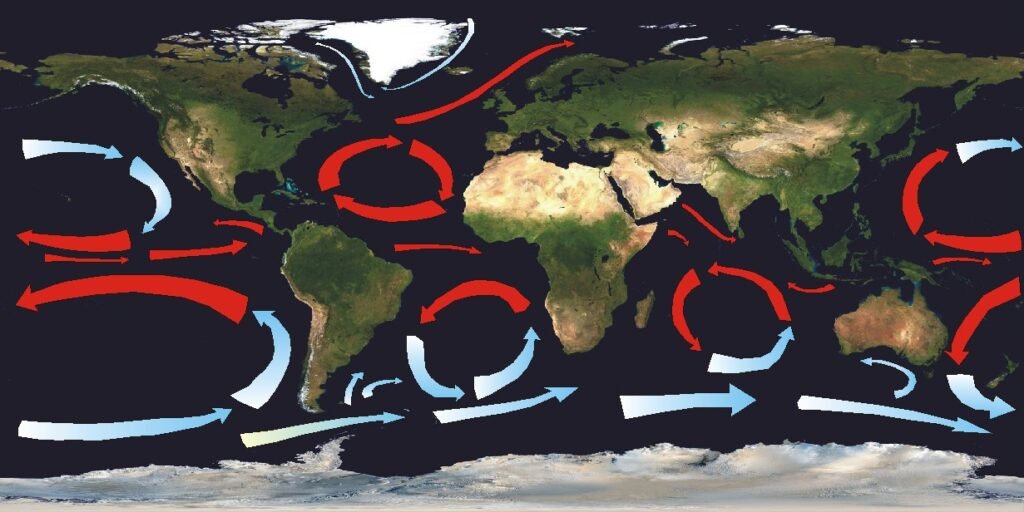

Scientists are tracking dramatic changes beneath the Atlantic Ocean’s surface that could reshape how Americans experience weather for decades to come. A warming climate doesn’t just affect dry land – it affects the ocean, too. For years, Earth’s ocean has acted as a heat sink for climate change: A large part of the heat generated by human use of fossil fuels is being absorbed by the ocean.

Recent research indicates the Gulf Stream system has shown signs of slowing in recent decades. This might sound small, yet ocean scientists warn that even slight shifts in these massive underwater highways can trigger cascade effects from Florida’s coastline to New England’s fishing grounds. The implications extend far beyond simple temperature changes, potentially altering everything from hurricane intensity to agricultural patterns across vast regions of North America.

The Gulf Stream’s Critical Role in American Weather

The Gulf Stream is a very strong current pressed up against the east coast of the United States. It brings warm water from the Gulf of Mexico into the North Atlantic, and it’s driven by the winds over the Atlantic. Think of it as nature’s heating system for the eastern seaboard.

It carries a substantial volume of water near Cape Hatteras in North Carolina. A cubic meter is about the amount of water in a bathtub, so there’s about 80 million bathtubs of water per second flowing through that section. The latter branch serves as a major heat source for the weather and climate of Western Europe. Great Britain and Scandinavia would be a lot colder if it weren’t for the Gulf Stream. It affects weather in the U.S., too.

Unprecedented Weakening Detected

Never before in over 1000 years the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), also known as Gulf Stream System, has been as weak as in the last decades. They found consistent evidence that its slowdown in the 20th century is unprecedented in the past millennium.

This marine circulatory system has reached notably weak levels in recent centuries, recent studies show, having lost about 15% of its strength since the mid-20th century. In early 2024, in a physics-based study using the latest generation of climate models, René van Westen and colleagues simulated the flow of fresh water until the AMOC circulation reached the tipping point. This was the first time the tipping point has been demonstrated in a state-of-the-art global coupled atmosphere-ocean climate model – unequivocal evidence that the tipping point exists.

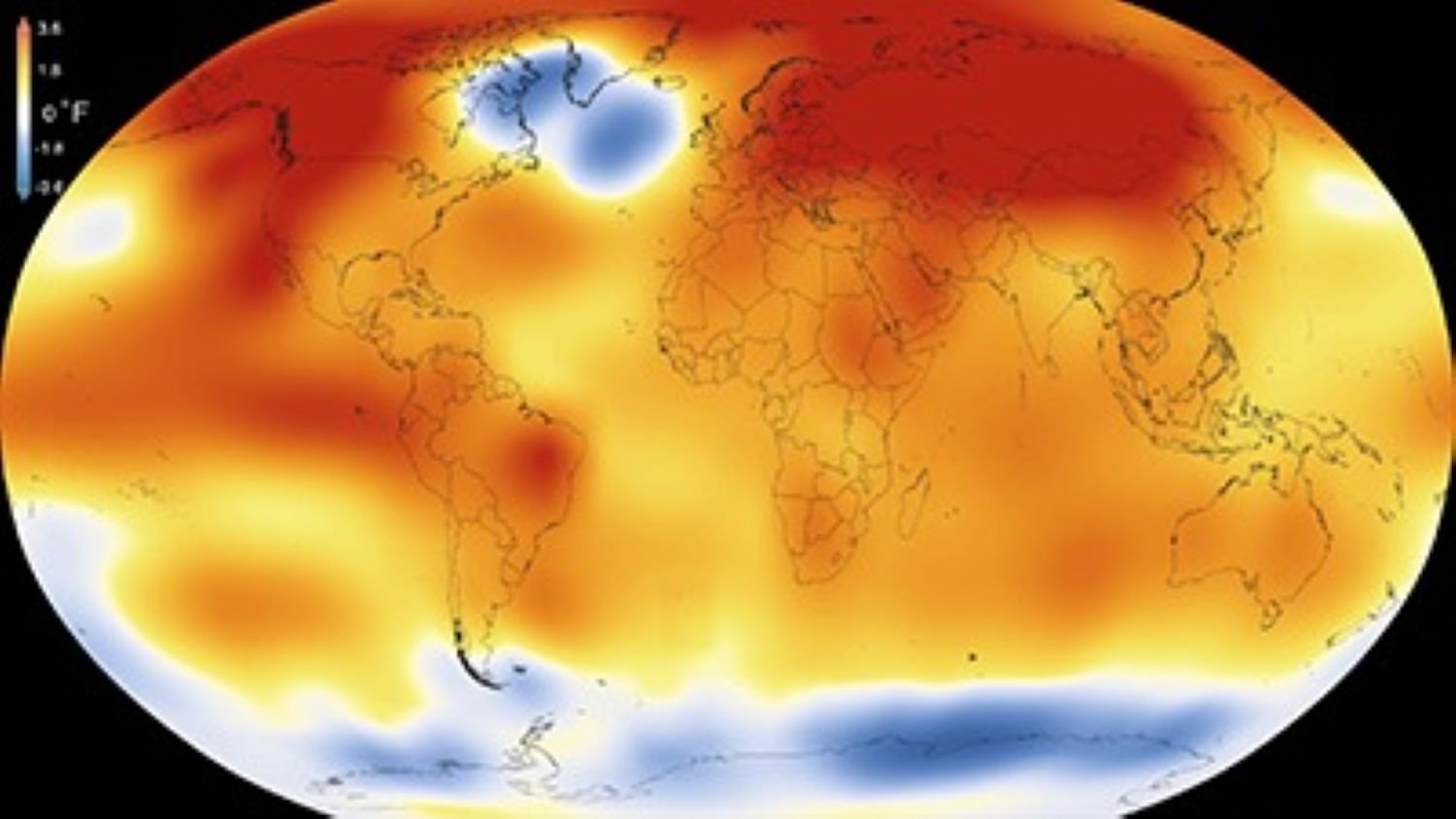

The Mysterious Atlantic Cold Blob

One of the most prominent indirect indicators of a weakening AMOC emerged in recent decades as an area of the subpolar Atlantic south of Greenland that has defied global warming – the infamous “cold blob” (also called the “warming hole”.) It is clearly shown in the figure below as the only area to cool over the last century while climate change warmed the rest of the world.

The cold blob – also known as a warming “hole” – can be spotted on maps of Earth’s changing surface temperature, appearing as a blue dot of cooling in a sea of red heat. As the water around it warms, the blob’s temperature has been dropping. Analysis of sea surface temperature trends and other indicators show that the cooler water in the cold blob is likely a result of reduced northward transport of warm water by the weakening AMOC.

Rising Sea Levels Along the Eastern Seaboard

“If you slow down the sinking of water in the North Atlantic, that means you have a pileup of waters along the eastern seaboard of the United States and the Gulf of Mexico,” said Brenda Ekwurzel, director of climate science for the Union of Concerned Scientists, an environmental group. “That means that you have increased regional sea level rise just from that ocean circulation change. So that’s not good for New York City, Norfolk or along Florida.”

“Several studies have shown that a slowdown of the [AMOC] exacerbates sea-level rise on the US coast for cities like New York and Boston,” Caesar said. A weaker Gulf Stream would mean higher sea levels for Florida’s east coast. The potential for sea level rise from the weakening Gulf Stream is just 10 centimeters. Still, 10 centimeters can be significant. That’s a few inches, so it’ll make the coastal flood impact of hurricanes greater.

Temperature Changes and Extreme Weather

Fundamentally, heat transport toward the north Atlantic will be strongly reduced, leading to abrupt climate shifts · Regions that are currently influenced by the Gulf Stream receive much less heat when the circulation stops. This cools North America and Europe. Atmospheric and sea-ice feedbacks will amplify the AMOC-induced changes, resulting in a very strong and rapid cooling of the European continent – predicted to cool 3ºC (over 5ºF) per decade, much faster than current global warming rates of 0.2+ C per decade.

And it could mean that a lot of the heat that would have gone to Europe would stay along the U.S. east coast and in Florida. “Your cooling mechanism to get that water to the north is slowing down,” she said. “This slowing down of your natural air conditioning, by getting that hot water from the Gulf Stream flowing northward, means that you have that hotter water sticking around and not getting out of your region as fast.”

Storm Patterns and Hurricane Intensity

Other studies have linked severe heat waves and storm patterns in northern Europe and the eastern United States to the weakened current. The warmer than normal Gulf Stream area can amplify the storms that approach the southeastern United States or the east coast. Especially problematic is the increased sea surface height, which also enables higher tides and potentially stronger storm surges.

In Europe, said the researchers, a further slowdown of the AMOC could imply more extreme weather events, for example a change of the winter storm track coming off the Atlantic, possibly intensifying the storms. “The cold blob can disturb the atmospheric jet stream and storm activities, so it has implications for extreme weather events in North America and Europe,” adds Li.

Impact on Marine Ecosystems and Fisheries

He said that a shifting Gulf Stream is already having a profound effect on East Coast fisheries, bringing more warm water fish into the area and disrupting seasonal patterns of fish and squid movement. “We know, for example, over the past 100 years that southeastern New England has been warming really fast compared to the rest of the eastern United States. And folks believe that that is related to gradual changes in ocean currents.”

These shifts aren’t just numbers on scientific charts. Fishermen from Maine to the Carolinas are witnessing species they’ve never seen before appearing in their nets. Traditional fishing grounds are changing as warm-water species follow altered current patterns northward. The economic implications ripple through coastal communities that have depended on predictable marine ecosystems for generations.

Future Projections and Tipping Points

The results showed that the circulation could fully shut down within a century of hitting the tipping point, and that it’s headed in that direction. Once we accumulate sufficient data for this EWS, we will be able to predict when the tipping point will be reached. “If we continue to drive global warming, the Gulf Stream System will weaken further — by an estimated 11 to 34 percent by 2100 according to recent climate model projections,” concludes Rahmstorf. This could bring us dangerously close to the tipping point at which the flow becomes unstable.

However, The researchers found that the AMOC will weaken by around 18 to 43 percent at the end of the 21st century. While this does represent some weakening, it does not represent substantial weakening that the more extreme climate model projections suggest. Still, Current projections from the IPCC show that the AMOC is unlikely to stop, or collapse, before the year 2100. However, “if such a collapse were to occur,” the IPCC says, “it would very likely cause abrupt shifts in regional weather patterns and the water cycle.”

Conclusion

The evidence points to a clear reality: America’s weather patterns are intimately connected to ocean currents that are already showing signs of significant change. While complete collapse remains unlikely this century, even moderate weakening could bring more extreme storms, rising seas, and unpredictable temperature swings to millions of Americans.

Realistically, adaptation to such a rapid change would be impossible. Yet understanding these changes gives us valuable time to prepare coastal defenses, adjust agricultural practices, and develop climate resilience strategies.

What would you have guessed about the ocean’s power to reshape an entire continent’s weather? Tell us in the comments.