A single sheet of parchment can spark a storm. Across labs and archives, researchers are re-reading the world’s oldest maps with new tools, asking whether ancient cartographers glimpsed a western land long before Columbus sailed. The idea is electrifying and uncomfortable: if a Roman-era world picture hid a clue to North America, entire chapters of U.S. pre could shift. Yet the path from tantalizing squiggle to proven coastline is steep, and the past is stubborn. What’s new in 2025 is not a smoking-gun map, but a wave of analytical power that is forcing old claims to stand up – or fall apart – under the brightest light yet.

The Hidden Clues

What if the trail to America wasn’t a straight line of ships, but a whisper in ink – a stray cape, a misdrawn island, a line that refuses to end where it should? That’s the allure behind the disputed maps now under scrutiny. Scholars are re-checking odd bulges along western ocean margins, unexpected place-names, and seemingly anachronistic coastlines that some claim hint at lands beyond the classical horizon.

Most anomalies have sober explanations: copyist errors, imaginative geography, or coastlines borrowed secondhand. Still, the pattern-hunters have a point – if multiple independent maps repeat the same odd shape, it deserves a microscope. The challenge is separating meaningful signal from medieval noise without leaping into fantasy.

A Roman-Era Puzzle

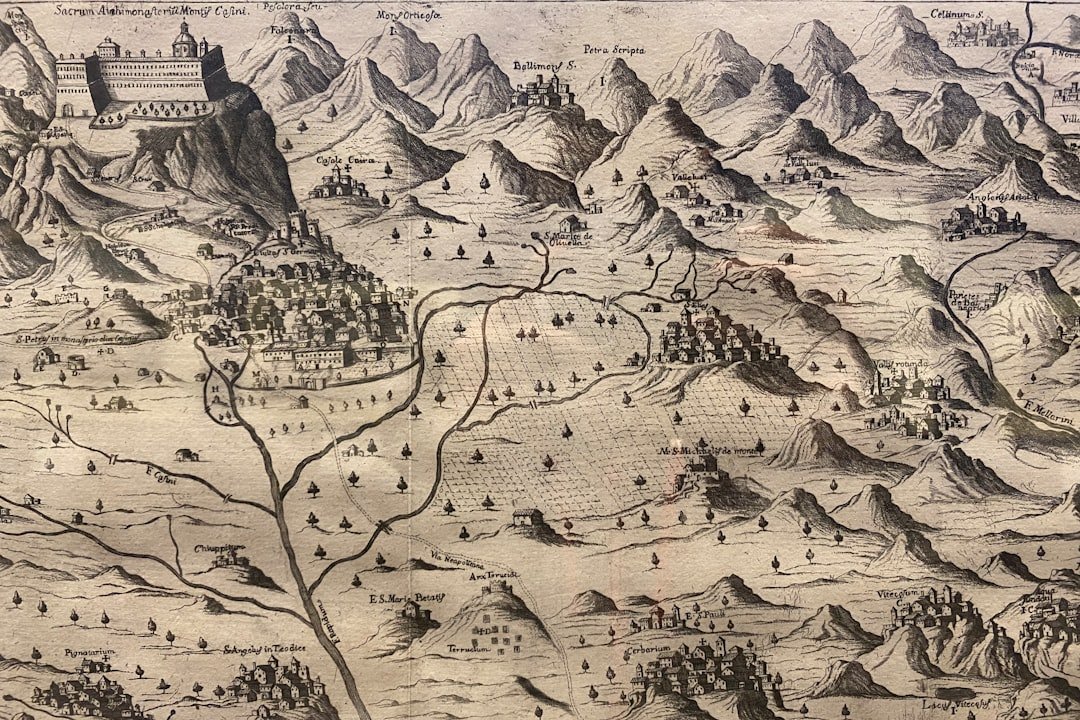

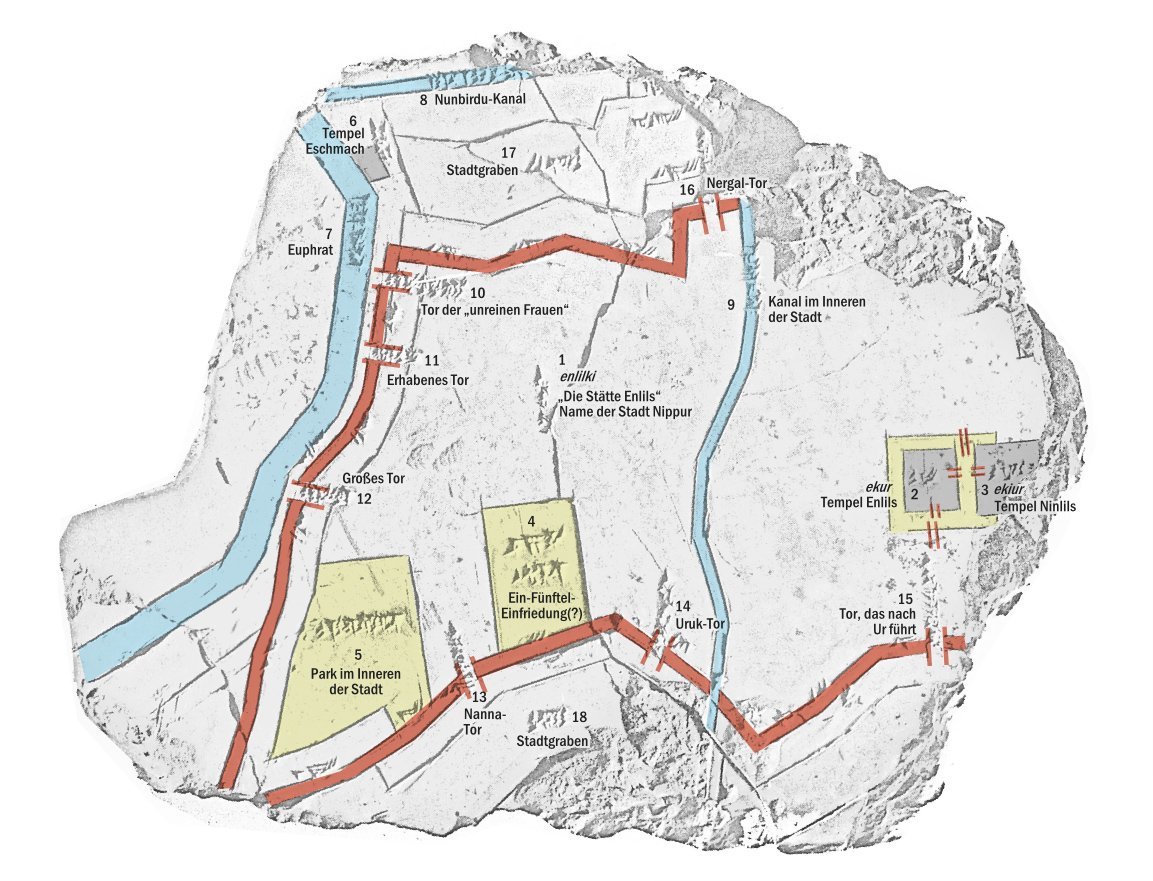

At the center of the 2,000-year question sits the legacy of Ptolemy, a second-century mathematician whose coordinate-based world reshaped how later mapmakers worked. We don’t have his original maps, only manuscripts and Renaissance reconstructions that applied his latitude–longitude grid to a much smaller globe. When modern researchers re-project these coordinates, strange western features can emerge, sometimes looking tantalizingly like land where there should be open sea.

Most historians caution that these shapes are artifacts of math – distortions from an undersized Earth and imperfect copying. And yet, it’s hard to ignore that Roman trade sailed far, hugging Atlantic coasts, and that currents could have carried wreckage or rumors across vast water. A single rumor rendered into a coastline would still be rumor, but it shows how easily possibility can harden into ink.

The Norse Map That Never Was

Few artifacts capture the highs and lows of this debate like the infamous map long claimed to show “Vinland” in medieval ink. For years it was brandished as proof that Europeans charted North America centuries before 1492. Then modern pigment testing identified a modern whitening compound in the lines, collapsing the claim and turning a sensation into a cautionary tale.

Ironically, the debunked map can obscure a real story: Norse sailors did reach North America, with archaeological sites in Newfoundland placing them around the turn of the first millennium. What we lack is a surviving medieval chart delineating those shores with confidence. That absence matters, because cartographic proof isn’t just about who arrived – it’s about who measured, mapped, and remembered.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

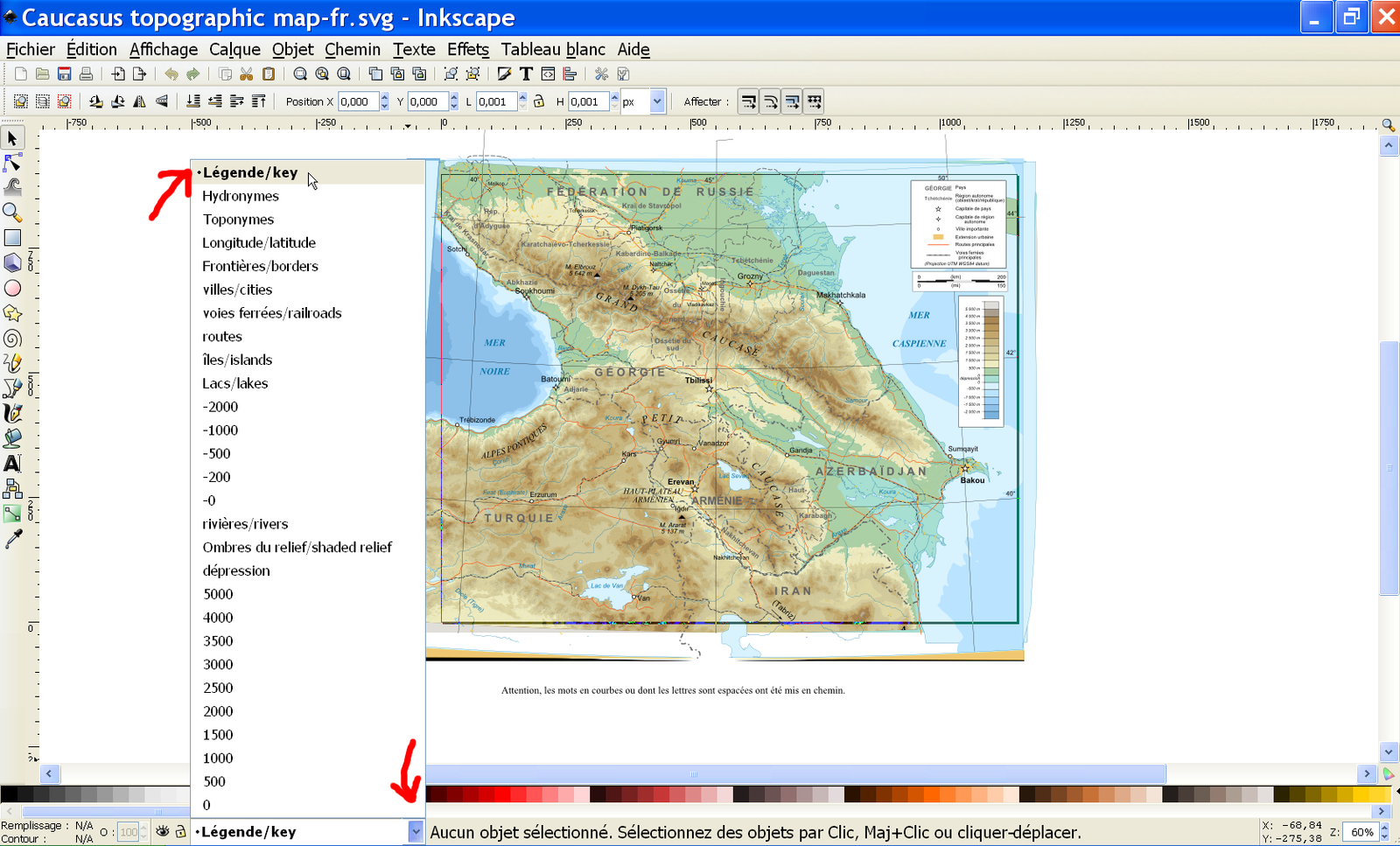

Cartography used to be read with magnifying glasses; now it’s scanned like a star. Multispectral imaging teases out erased notes, while X-ray fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy pick apart pigments and binders, telling us which strokes belong to which century. Radiocarbon analysis narrows the age of parchment, and even protein fingerprints can hint at the animals used to make it, building timelines from molecules.

Beyond the lab bench, geographers overlay ancient coastlines onto modern grids, testing whether a supposed “mystery shore” truly aligns with any real place. I once spent an afternoon tracing a faded cape that looked eerily familiar – until a different projection showed it collapsing back into a known European headland. The lesson sticks: technology reveals, but it also corrects our wishful eyes.

Analysis: Why It Matters

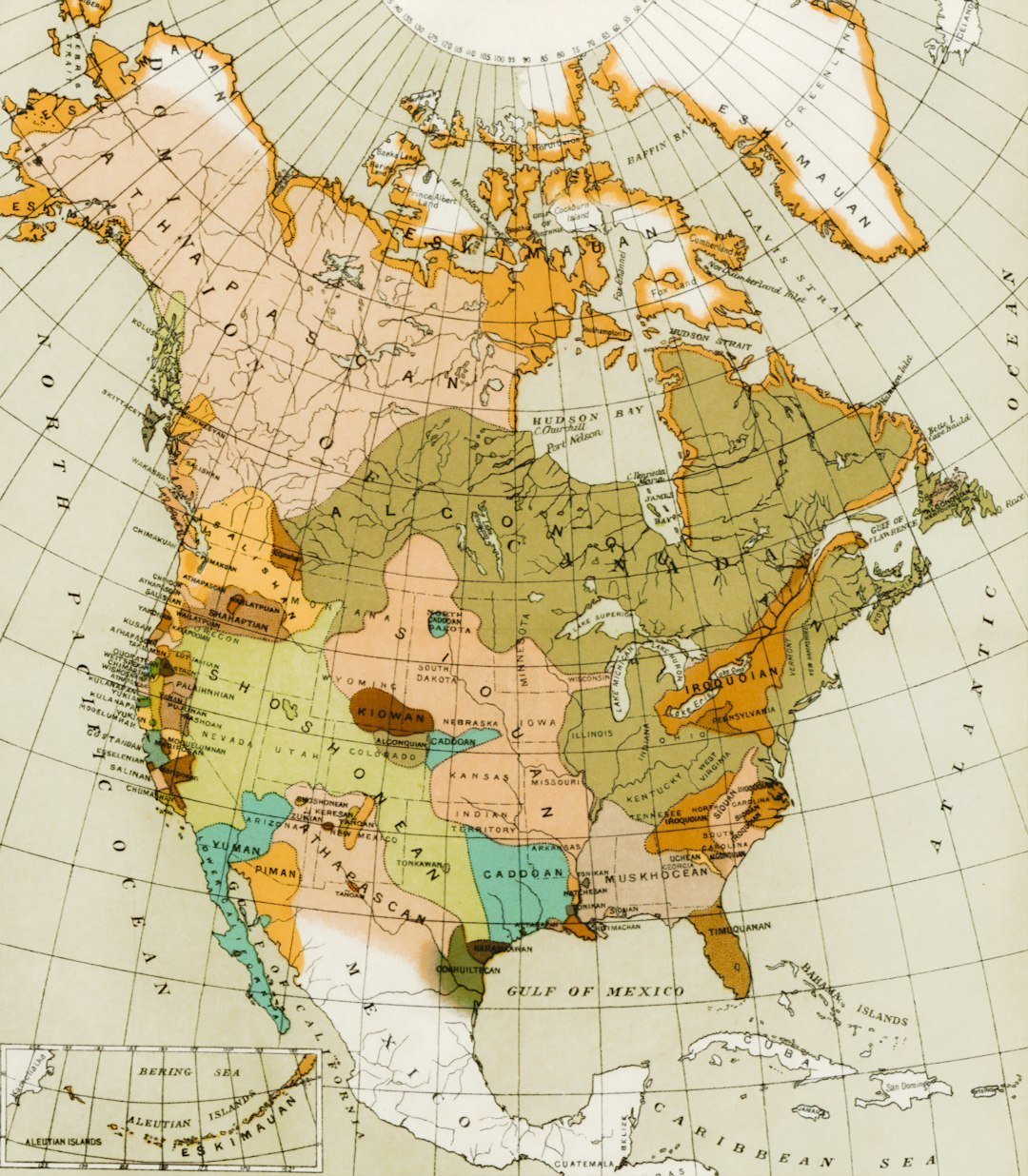

Maps are more than pictures; they’re claims about the world, and in the U.S. those claims shape origin stories. If credible evidence showed Old World cartographers sketched parts of North America before the Age of Discovery, it would force a rethink of early contact zones, risk routes, and the speed at which knowledge travels. It would also demand a careful integration with Indigenous histories, which record presence and complexity long before any European pen wandered west.

Compared with traditional textual scholarship, today’s analyses operate like a double-checking engine: chemical tests verify dates, imaging re-reads the margins, and geospatial models test geometry against coastlines. This convergence tightens the standard of proof and trims the myth from the map. In a field that has swung between romantic speculation and hard-nosed skepticism, that balance is overdue.

Global Perspectives

The debate stretches far beyond Europe’s libraries. Ottoman, Arab, and Chinese mapmaking traditions all grappled with partial data and big oceans, leaving behind charts that mix precise coasts with expansive guesswork. Some Renaissance world maps, influenced by Mediterranean portolan charts and guarded state secrets, appear to leap ahead of their time, sketching western shores with confidence that likely came from rapid post-1492 intelligence, not ancient voyages.

The Piri Reis chart, for instance, compiles earlier sources into a striking mosaic of the Atlantic, while sixteenth-century French Dieppe maps blend rumors and reconnaissance into seductive southern continents. Read generously, they suggest fast information flows; read cautiously, they reveal how cartographers filled gaps with imagination. Either way, they remind us that maps don’t just record discovery – they manufacture it.

The Future Landscape

What happens next will be decided as much by software as by scholarship. AI-assisted paleography is beginning to classify letterforms and hands, flagging later insertions that betray a too-modern coastline, while image forensics can detect minute pressure changes in quill strokes that reveal retouching. High-resolution scans are being stitched into global datasets, allowing researchers to test alignments against bathymetry and paleo–sea level models.

The most exciting frontier may be provenance at scale: isotope analysis of parchment and inks tied to regional baselines, micro-CT scans of bindings that trap earlier map fragments, and open repositories that let skeptics and enthusiasts interrogate the same pixels. If a 2,000-year-old world picture does contain a defensible hint of America, these tools will find it – and just as importantly, they’ll keep us honest when a tempting outline is only a mirage.

Conclusion

Curiosity is the spark, but rigor is the compass. Support museums and archives that share high-resolution scans, advocate for open data so independent teams can replicate results, and be cautious when a dramatic map claim spreads without lab-backed details. If you teach or mentor, use disputed maps to model critical thinking: ask what the evidence is, how it was tested, and what competing explanations remain.

And if you’re lucky enough to stand before a fragile chart, let wonder in – but let skepticism steer. The past doesn’t mind being questioned, only being misread. What coastline would you trust your compass to trace?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.