When you think of , probably the first things that come to mind are those famous colorful logs turned to stone. But beneath this stunning landscape lies a treasure trove of ancient secrets that’s rewriting what we know about life on Earth over 200 million years ago. Scientists are discovering that this park isn’t just home to beautiful petrified wood – it’s actually one of the most important fossil sites in the world for understanding the Triassic period. The discoveries coming out of this desert landscape are so exciting that paleontologists describe it like hitting the jackpot, with each new find offering fresh glimpses into an ancient world we never knew existed. So let’s dive into the incredible fossil discoveries that are changing everything we thought we knew about prehistoric Arizona.

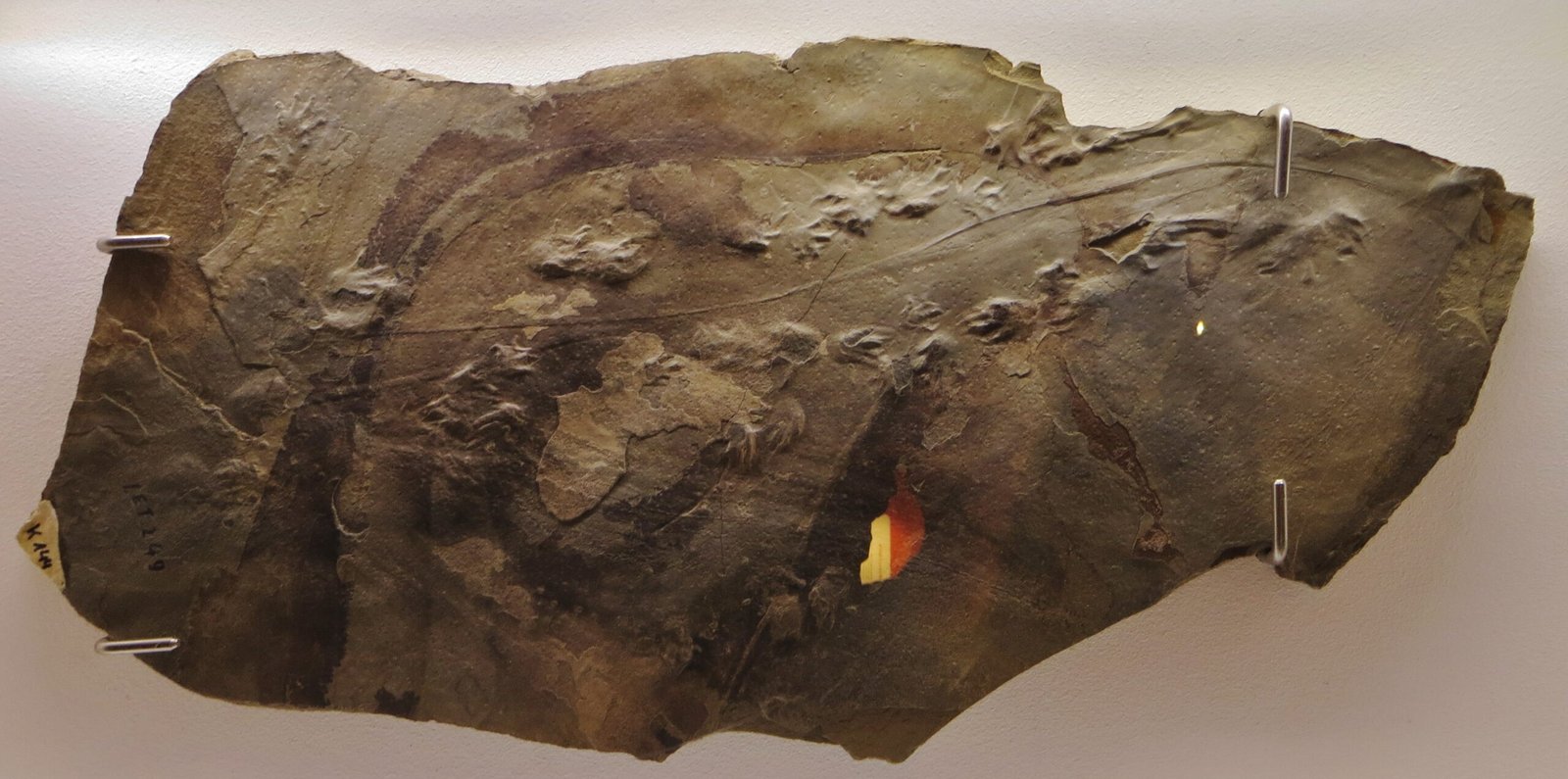

Thunderstorm Ridge Emerges as a Fossil Goldmine

Deep within the park’s eastern expansion lands sits a place that would make any fossil hunter’s heart race – Thunderstorm Ridge, which has been key to new discoveries of small-bodied animals. Discovered about a decade ago, paleontologists noticed this site while prospecting rock outcrops on land that was added to the park. The fossil site is named Thunderstorm Ridge after Park Paleontologist Bill Parker was caught in a thunderstorm while digging there.

Kligman remembers seeing coprolites weathering out of a hill and swinging his pickaxe to get past the rock on the surface. The first chunk of fresh rock that he pulled out had a “four-inch-long jaw of a reptile sticking out of it”. What they found was absolutely mind-blowing – they have around 7,500 specimens in the Petrified Forest collection just from Thunderstorm Ridge alone, although the fossils they are finding are so small this only takes up a small portion of a storage cabinet.

The Long-Necked Wonder: Akidostropheus Oligos

Paleontologists and partners with the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, who made the discovery, named the species Akidostropheus oligos. This incredible creature is unlike anything you’d expect to find in Arizona today. Akidostropheus Oligos was an aquatic reptile with a neck longer than both its body and tail combined. Its neck is believed to be twice as long as the body and tail combined. For comparison, giraffe necks generally make up one-third of its total body length.

It swam and lived in the warm, swampy ponds and small rivers of northern Arizona during the Triassic period. The Akidostropheus oligos fossils revealed extremely small, spiked bones, a unique feature of the creature. She says the species was given the Greek name Akidostropheus Oligos, meaning tiny, spiked backbone. “The vertebrae we found have these really cool spikes coming out of the vertebrae, which is why we got to name it a new species because there are no other vertebrae that belong in Tanystropheidae that have that spike on it”.

North America’s Oldest Flying Reptile Takes Flight

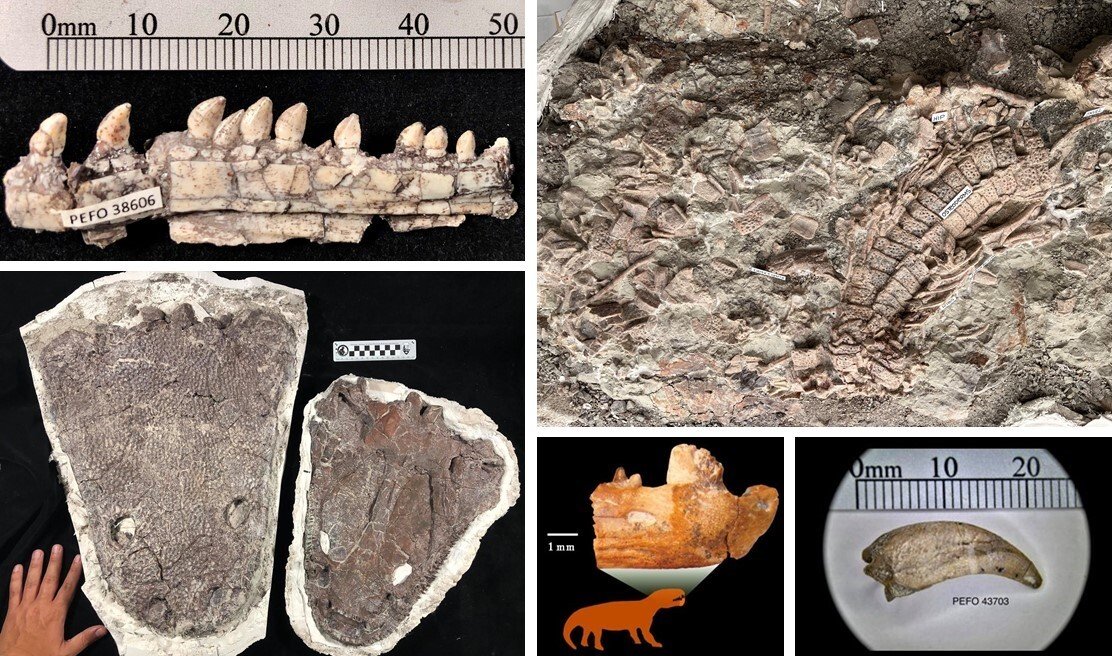

A Smithsonian-led team of researchers have discovered North America’s oldest known pterosaur, the winged reptiles that lived alongside dinosaurs and were the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight. In a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers led by paleontologist Ben Kligman, a Peter Buck Postdoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, present the fossilized jawbone of a new pterosaur species and describe the sea gull-sized flying reptile along with hundreds of other fossils they unearthed from the site.

The winged reptile would have been small enough to comfortably perch on a person’s shoulder. The remarkable fossil was unearthed by preparator Suzanne McIntire, who volunteered in the museum’s FossiLab for 18 years. “What was exciting about uncovering this specimen was that the teeth were still in the bone, so I knew the animal would be much easier to identify,” McIntire said. The discovery offers scientists crucial insights into how these ancient flying creatures lived during Earth’s distant past.

Ancient Turtles Tell Their Own Story

The researchers also described the fossils of an ancient turtle with spike-like armor and a shell that could fit inside a shoebox. This tortoise-like animal lived around the same time as the oldest known turtle, whose fossils were previously uncovered in Germany. The discovery is particularly fascinating because “This suggests that turtles rapidly dispersed across Pangaea, which is surprising for an animal that is not very large and is likely walking at a slow pace,” Kligman said.

These ancient shelled creatures provide important clues about how quickly early species spread across the supercontinent Pangaea during the Triassic period. The fact that similar turtle fossils appear in both Germany and Arizona around the same time suggests these creatures were more mobile than scientists previously thought. Their presence in the fossil record also marks an important evolutionary milestone – the emergence of one of nature’s most enduring body plans.

The Funky Worm Discovery

One of the most unusual discoveries has to do with the world’s oldest known caecilian fossils. A team of paleontologists from Virginia Tech and the U.S. Petrified Forest National Park, among others, have discovered the first “unmistakable” Triassic-era caecilian fossil – the oldest-known caecilian fossils – thus extending the record of this small, burrowing amphibian by roughly 35 million years. “Seeing the first jaw under the microscope, with its distinctive double row of teeth, sent chills down my back,” Kligman said. “We immediately knew it was a caecilian, the oldest caecilian fossil ever found, and a once-in-a-lifetime discovery.”

But here’s where things get really interesting – The genus name “Funcusvermis” was inspired by the 1972 song “Funky Worm” from the album Pleasure by the Ohio Players; a favorite song that was often played while we were all excavating fossils. At the Petrified Forest National Park, where the initial discovery was found in 2019, the lower jaws of at least 70 individuals of Funcusvermis have been recovered as of summer 2022, making the area “the most abundant fossil caecilian-producing bonebed ever discovered,” Kligman said.

A Chipmunk-Sized Mammal Relative

One of the most significant recent discoveries is a newly described species of cynodont, or stem mammal: Kataigidodon venetus. Kligman described it as “a little chipmunk-sized animal.” “If you were to see it, the only thing that you would really notice different than a rat or a chipmunk or a hamster is that they wouldn’t have an ear,” Kligman said.

Kligman and the research team named the fossil Kataigidodon venetus, which translates roughly to “blue thunderstorm tooth” in Greek and Latin, referring to Thunderstorm Ridge, the area of Blue Mesa where the fossil was found. Kligman found the minuscule fossil by scouring the contents of a sediment bag under the microscope in the lab. Fossils in this layer of rock are so small that paleontologists collect sediment and rock in the field and then examine it under magnification.

The Underground Digger: Skybalonyx

Another recent find, described by Xavier Jenkins, an Idaho State University Ph.D. student and PEFO paleontology intern in 2019, is Skybalonyx skapter, a species new to the science of an extinct reptile in the Drepanosaur group, a lineage of reptiles that lived in the Triassic period 220 million years ago. About the size of modern iguanas, this species differs from other drepanosaurs in that it is a burrowing animal rather than a tree dweller. Skybalonyx skapter has unusual hand claws, much wider than those of other drepanosaur species, used for burrowing.

It likely spent most of its life underground. Skybalonyx skapter means “digging dung claw” from Ancient Greek, referring to the abundant fossilized dung found alongside the fossil bone at Thunderstorm Ridge. This discovery highlights just how diverse life was during the Triassic period, with creatures adapted to every imaginable lifestyle from flying through the air to tunneling deep underground.

Revolutionary Fossil Collection Techniques

Fossils were collected by painstakingly slow paleontological procedures, including hand quarrying and screenwashing, microscope-assisted picking, preparation using consolidants, adhesives, pneumatic air scribe, and pin vice. They were found by collecting large amounts of rock from the site, rinsing that rock with water through fine metal screens, and looking at it under a microscope to find the tiny fossils.

The methods being used at Thunderstorm Ridge represent a revolution in paleontology. Instead of just looking for big bones sticking out of rocks, scientists are now processing tons of sediment to find fossils smaller than your fingernail. One of the more interesting features of this bone bed, Kligman said, is that the microfossils are primarily found in a layer he described as “a conglomerate of fossilized poop.” This means researchers are literally searching through ancient bathroom deposits to find some of the most significant fossils ever discovered.

The Coprolite Layer Mystery

Fossils of these animals and others found in the Chinle Formation are often found within layers of rock deemed the coprolite layers – beds identified by high concentrations of coprolites, or fossilized poop, Kligman says. These layers “had been looked at in quarries going back to the early 1900s, but what people were excavating from them were the large bones,” he says. The tinier bones around them were often ignored, or deemed to be fish scales.

This discovery has completely changed how paleontologists approach fossil hunting. What was once considered unimportant debris is now recognized as one of the richest sources of prehistoric life information on the planet. The fact that so many important fossils are preserved in these fossilized waste layers suggests that these ancient environments were incredibly rich with life, supporting diverse ecosystems of creatures both large and small.

Prehistoric Arizona: A Tropical Paradise

When Kataigidodon lived 220 million years ago, the Petrified Forest was not made of stone. It was a humid, lush tropical forest that was close to the equator. The sediments that make up the Chinle were deposited between about 227 and 205 million years ago, when Arizona was close to the equator. The environment at the time was much different than it is today, Marsh says, as it was a landscape of floodplains, ponds, and meandering rivers.

“It’s full of all of these different animals,” Kligman said, noting that there were ancestors of lizards, early dinosaurs and ancient amphibians living in and around ponds and rivers. When they died, their bones were washed into various depressions and buried by sediment, only to be dug up 220 million years later in an environment that’s now a desert. This dramatic environmental shift helps explain why so many diverse fossils are preserved in what’s now one of America’s most arid landscapes.

More Discoveries on the Horizon

“There is a lot in the pipeline and even more still to be discovered at Petrified Forest,” he adds. “Every time it rains, you have the chance that something in those 500 localities is eroding out.” Kligman said this is only the beginning of the discoveries coming from this area of the park, and more descriptions of new species are on the horizon. According to what paleontologists have uncovered so far, this bone bed is exceptionally rich and contains a diversity of animals from this time period that is found nowhere else in the world.

There are upwards of 500 known vertebrate fossil sites in the park, including bonebeds containing numerous specimens from a variety of species. The sheer number of sites means that paleontologists could spend decades exploring just this one national park and continue making groundbreaking discoveries. Each rainstorm potentially exposes , making every visit to the park a potential opportunity for scientific breakthrough.

Conclusion

Arizona’s Petrified Forest is proving to be far more than just a collection of beautiful stone logs. It’s become ground zero for understanding one of the most important periods in Earth’s history – the dawn of the age of dinosaurs. From tiny mammal relatives no bigger than chipmunks to long-necked aquatic reptiles and North America’s oldest flying creatures, the diversity of life preserved in these ancient rocks is simply staggering.

What makes these discoveries even more remarkable is that most of them are coming from fossils smaller than your thumb, hidden in layers of fossilized poop that previous generations of paleontologists had largely ignored. The revolutionary techniques being used to find these microscopic treasures are opening up entirely new windows into prehistoric life, showing us that the ancient world was far more diverse and complex than we ever imagined.

As scientists continue to process sediment from sites like Thunderstorm Ridge and explore the park’s hundreds of fossil localities, who knows what other incredible creatures they’ll uncover? What do you think about these amazing discoveries? Tell us in the comments.