On certain blue-sky mornings along the Outer Cape, the sea looks calm enough to drink. Then a fin cuts the surface, and the familiar, uneasy thrill runs down the beach. Cape Cod’s great white sharks are back in force, and this time the story isn’t just fear – it’s science catching up with one of the ocean’s most elusive hunters. Researchers are learning how these predators navigate crowded coastlines, follow rebounding seal populations, and ride shifting temperatures like a moving highway. The comeback is real, it’s complicated, and it’s changing how people and predators share the sandbar edge.

The Hidden Clues

Scientists start with the basics: who’s here, when they arrive, and why they stick around. The clues hide in water temperature maps, seal haul-outs, and even scratches on dorsal fins that help identify returning individuals. Patterns emerge – late summer through early fall tends to be prime season, especially where sandbars funnel prey close to shore. I remember standing on a dune one September and seeing that unmistakable slice of gray, a reminder that this coastline is alive in ways we barely perceive.

Those moments feel cinematic, but the work behind them is meticulous. Teams scan from boats, planes, and bluffs, cataloging fins the way birders log warblers. Each sighting becomes part of a living archive that tells a story of movement and memory along the Cape’s exposed rim.

From Seals to Sharks: A Protected Food Web Rebuilt

The sharks didn’t return by accident; the ecosystem rolled out a welcome mat. After decades of decline, gray seal numbers rebounded under strong protections, rebuilding a prey base that large sharks can’t ignore. The result is a coastal food web asserting itself, with energy moving from forage fish to seals to the apex predator that evolved to hunt them. Instead of a quiet shoreline, we have a dynamic, restored stage.

That restoration brings tradeoffs. More seals mean more sharks in shallow hunting corridors where people swim and surf. It’s not a story of villains and heroes so much as one of cause and effect – a protected species doing what protection intended, and a top predator responding exactly as nature designed.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Early shark studies relied on chance encounters and fishermen’s logs, offering fragments of a vast, drifting puzzle. Today the toolkit is breathtaking: acoustic tags ping through seafloor receivers, satellite tags beam travel arcs, and drones skim the boundary layer for real-time sightings. Photo-identification ties it together, using fin notches like fingerprints to track individuals across seasons. Stitch those threads into a map, and you see behavior, not just presence.

The approach resembles astronomy more than old-school fieldwork – pulling faint signals from a noisy universe. With each pass, the models sharpen, and the Cape’s shark traffic looks less like chaos and more like commuter flow during rush hour. The difference is that commuters don’t have teeth up to 2-3 inches long.

Reading the Water

For white sharks, the Cape is a patchwork of opportunity zones. Sandbars push baitfish and seals into narrow lanes, tides tug scent trails along the beach face, and water temperature sets the daily rhythm. On flat-light days, the surface can hide hunting sharks just beyond the final sandbar, close enough to feel like the next wave could carry them in. The ocean seems empty; it often isn’t.

Risk isn’t random, though it can look that way from a beach towel. Scientists pair sightings with environmental conditions, building probabilistic maps that forecast when and where sharks might concentrate. It’s less a crystal ball than a weather report, but it’s miles better than guessing.

The Science of Tracking

Tagging has become the backbone of Cape Cod shark research, each tag a tiny narrator of a life we rarely witness. Acoustic tags reveal who swings past the receivers along favored routes, while satellite tags sketch out long-distance migrations beyond the Cape’s horizon. Paired with machine-learning tools that sift waves and shadows, the data turns a murky world into a legible script. You can’t manage what you can’t measure, and this is measurement at scale.

Even simple tools matter. Beach managers use standardized flags, posted alerts, and trained spotters to translate science into choices at the shoreline. I’ve seen surfers pause at the access trail, scan the app on their phone, and decide: paddle now or wait for the tide to shift.

Why It Matters

Sharks concentrate energy at the top of the food web, shaping the behavior of prey and balancing coastal ecosystems. When apex predators vanish, prey become reckless, habitat degrades, and the system loses its checks and balances. The Cape’s resurgence of white sharks signals that the web, while tense and sometimes scary for swimmers, is functional again. That’s not just an ecological footnote; it’s a benchmark for recovery.

It also reframes safety. Traditional beach rules focused on rip currents and sunburn; now managers add bite-prevention strategies, first-aid training, and rapid response plans. The comparison is stark: yesterday’s ocean literacy was about waves; today’s includes predators and probabilities. Better information means better decisions, even if the ocean never offers guarantees.

People and Predators Share a Beach

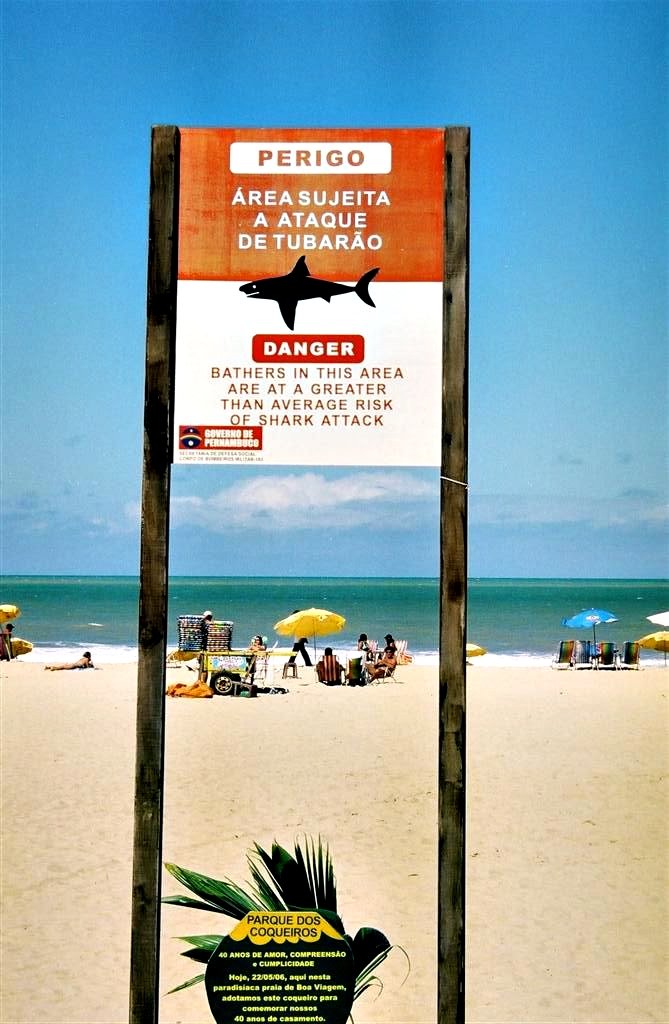

The human side of this story hums in parking lots and kitchen-table debates. Families want summer memories, surfers want clean drops, and no one wants a close encounter with a hunting shark. On the Cape, coexistence looks like changing habits – staying out of murky water near seals, avoiding isolated sandbars, and heeding closures when conditions favor predators. It’s not surrender; it’s respect for a place where wildness still writes the rules.

Local communities have adapted quickly. Lifeguards carry trauma kits and practice bleeding-control drills, while town boards coordinate messaging so advice doesn’t shift from beach to beach. The tone is pragmatic, not panicked, and that makes all the difference.

The Data Behind the Dorsal

Numbers aren’t just tallies; they’re stories with edges and caveats. A sharp uptick in detections can reflect better receivers rather than more sharks, and seasonal returners can look like new arrivals if you don’t link identities. Scientists lean on mark-recapture models and consistency checks to avoid counting echoes as individuals. It’s careful accounting in a world with few straight lines.

Consider a simple snapshot that often helps beachgoers:

- Peak activity tends to cluster from midsummer into early fall, when water temperatures suit predators and prey.

- Nearshore encounters are more likely around seal haul-outs, outer sandbars, and steep drop-offs that funnel movement.

- Clear visibility and lifeguard coverage improve detection, but sharks can still hunt unseen in glare or chop.

Global Perspectives

Cape Cod isn’t alone. From South Africa to Western Australia and the Mediterranean’s recovering pockets, white shark stories track the same arcs of protection, prey rebound, and shifting climate. The Cape offers a high-resolution case study because the coastline is compact and the research investment is intense. Lessons learned here – especially about real-time alerts and public communication – travel well across oceans.

There’s also humility in the global picture. Populations rise locally and remain fragile globally, with threats ranging from bycatch to habitat change. The Cape’s success is a reminder that conservation can work, but it’s not an endpoint; it’s a maintenance plan that needs constant attention.

Myth vs. Reality

Myths thrive where details are scarce, and sharks are master subjects for half-truths. Reality checks help: these predators aren’t patrolling for people; they’re keying in on seals and structure. Most days, the busiest shark lanes can be predicted, avoided, or at least approached with caution informed by data. The ocean doesn’t owe us certainty, but it rarely behaves like a monster movie.

The best antidote to myth is contact with evidence. Watch a tagging video or study a movement track, and fear settles into respect. That shift – from dread to informed caution – opens space for smarter beach culture, not braver recklessness.

The Future Landscape

Coming tools read like sci‑fi: AI that flags shark shapes in drone feeds, predictive risk dashboards that update with tide and light, and smarter tags that log fine‑scale hunting behavior. As coastlines warm and prey distributions slide, models will likely extend the season by forecasting new hotspots before swimmers arrive. The goal isn’t to sterilize the ocean but to give communities a head start on risk.

Challenges remain. Data needs funding, equipment breaks in saltwater, and messages must land with clarity on crowded summer days. The big test will be scaling what works on the Cape to longer coastlines without losing nuance. If we get that right, coexistence stops being a slogan and becomes daily practice.

How You Can Help

Coexistence starts small and local. Swim near lifeguards, skip seal-dense sandbars, and keep your eyes on posted alerts before and during your beach day. If you surf, go with a buddy, avoid low-visibility conditions, and keep sessions shorter during peak predator hours. None of this drains the joy; it simply stacks the odds in your favor.

Support the science that underpins those choices. Back local research groups, volunteer for beach monitoring programs, and engage with community meetings where safety plans are shaped. The ocean repays attention with wonder, and a little humility goes a long way toward keeping that wonder intact. Did you expect that?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.