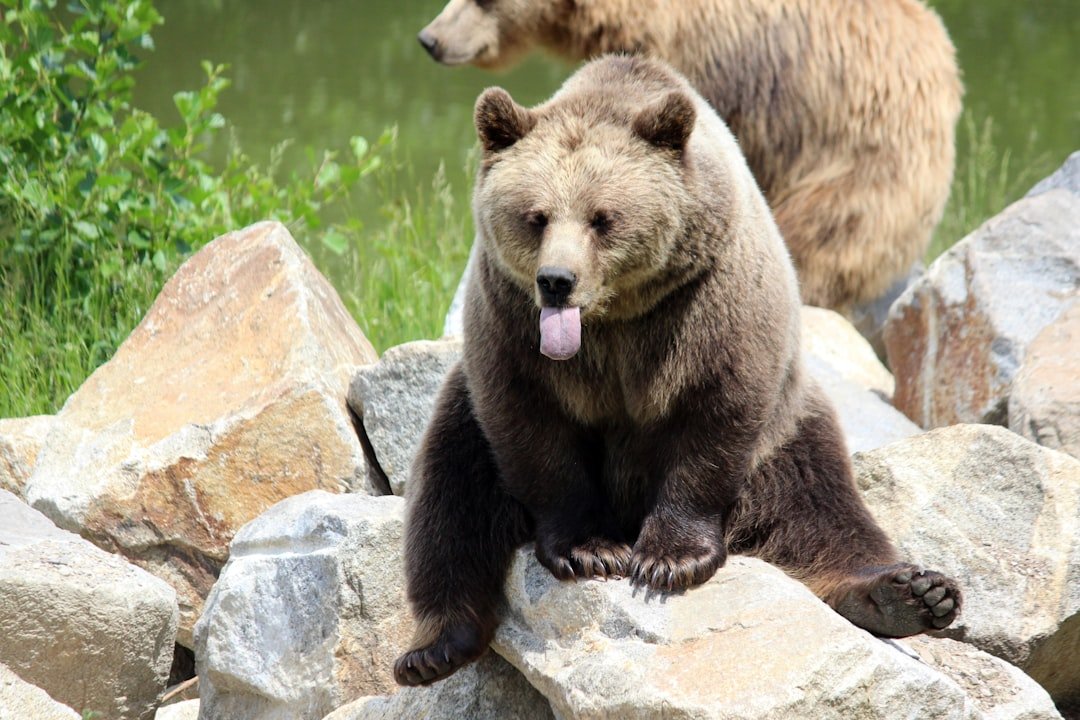

On busy summer evenings in the Great Smoky Mountains, you can feel a quiet negotiation unfolding between people and bears. Hikers stream off the trails, headlights ribbon the valleys, and somewhere in the understory a black bear pauses, listens, and changes course. The park holds roughly about two bears per square mile, an astonishing density for the eastern United States, and it’s reshaping how these animals solve problems, find food, and avoid us. New research doesn’t argue that bears suddenly evolved bigger brains; it shows they’re learning faster, flexing memory and strategy to navigate a landscape filled with tourists, cabins, and cleverly latched trash cans. That adaptability – and our choices – will decide whether this story remains wondrous or turns worrisome.

The Hidden Clues

Here’s the surprising part: as human routines intensify in the Smokies by day, bears increasingly shift their movements to the shadows of night. Motion-triggered cameras and GPS collars reveal a pattern of calculated risk, with bears threading routes past homes and trailheads when human activity dips, then melting back toward cover by dawn. That’s not random; it’s behavioral fine-tuning that takes memory, timing, and a steady feedback loop of trial and error. I’ve watched it play out from a backcountry campsite, hearing the faint pad of paws and a twig snap just after midnight, then nothing but crickets again. In a park this crowded, silence is a strategy – and bears are getting very good at it.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Captive studies show black bears can learn with touchscreens, discriminate quantities, and recognize categories, a toolkit that maps neatly onto wild life in a tourist-heavy park. Those same cognitive building blocks help a Smokies bear decide whether to nose a cooler, test a cabin latch, or bypass both because last week it ended badly. Researchers track these choices with GPS units that ping every few minutes outside the park boundary and less frequently inside, producing movement heat maps that look eerily like commuter traffic. The data make one thing clear: even bears deep in the woods occasionally venture into edge communities to sample opportunities and then adjust their routes based on what worked. In practical terms, that’s intelligence doing what intelligence does – generalizing lessons and applying them in new places. It’s not magic; it’s learning, scaled up to a rugged mountain range.

How Bears Learn: Mothers, Mistakes, and Memory

Wildlife biologists increasingly view “smarts” in bears as a blend of social learning and individual innovation. Cubs pick up foraging habits from their mothers – where to dig for grubs, when to raid acorns, which smells mean danger – and some also stumble into novel tricks on their own. Studies in western parks found that offspring of conflict-prone females were more likely to test human foods later, yet other work showed plenty of young bears adopt bad habits without parental coaching. That mixed picture is actually good news for management because it points to leverage on both sides: protect mothers from food rewards and you reduce transmission, secure the human foodscape and you choke off the incentive for would‑be innovators. In the Smokies, that means the same lesson holds whether a bear “learned” at a dump or never got the chance – locking up attractants cuts curiosity at the root.

The Smokies in Motion: What GPS Collars Reveal

Recent collaring projects around the park boundary underline just how dynamic these bears have become. Males, with their larger ranges, were especially likely to leave the park at some point, and well over half of collared females did too, particularly in lean spring periods and high‑calorie fall weeks. The collars log positions every couple of hours in the backcountry but speed up to minutes once bears hit towns, giving scientists a crisp look at alleyway strolls, creek crossings, and quick detours behind restaurants. Those tracks show bears exploiting quiet windows – weekday predawn, post‑storm evenings – then angling back to the forest, behavior that aligns with research from other states showing nocturnal passes through developed areas. In blunt terms, the Smokies are a classroom, and the curriculum includes traffic patterns, trash schedules, and when porch lights switch off.

Why It Matters

This matters because behavior is the fastest moving part of wildlife change, and it’s happening on a timeline of days and weeks, not generations. Traditional management once leaned heavily on relocation or lethal control, but studies increasingly show those approaches don’t reliably reduce conflicts when unsecured food remains abundant. By contrast, communities that deploy bear‑resistant containers and reach broad compliance see conflicts drop by roughly about three fifths, often immediately, which is an astonishing return for a simple fix. That’s a scientific endorsement of prevention over punishment – and an acknowledgment that bears are learning from our patterns as much as we are from theirs. If we keep broadcasting easy rewards, their cleverness will find them; if we shut the door, their cleverness takes them back to acorns and berries.

Global Perspectives

While the Smokies are unique in scale and visitation, the cognitive playbook unfolding here mirrors patterns reported from Massachusetts to the Rockies. In several regions, bears preferentially traverse developed areas at night, an elegant workaround that keeps calories high and contact low. Camera studies show bears toggling their daily rhythms when hunting seasons or heavy recreation spike, a sign of flexible decision‑making rather than blunt avoidance. In mountain towns that switched from ordinary cans to truly bear‑resistant models, the street‑by‑street data show bears try, fail quickly, and move on, a small story that adds up to big conservation dividends. The common thread is striking: where human behavior reduces payoffs, bear behavior reverts to wilder habits, and conflicts fade without heavy‑handed measures.

The Future Landscape

What’s next looks surprisingly high‑tech for a centuries‑old coexistence puzzle. Managers are testing smart‑latched dumpsters, cellular trail cameras with automated alerts, and neighborhood dashboards that map nightly bear activity like a weather radar. On the research side, lighter GPS collars and machine‑learning models are beginning to connect food pulses – mast failures or bumper berry seasons – to street‑level bear decisions in near‑real time. There are challenges: privacy concerns, cost, and the risk of pushing bears toward riskier foraging if communities adopt tools unevenly. But the trajectory is hopeful because each new piece of tech hinges on the same premise the bears already follow – learn fast, adapt faster, and minimize unnecessary risk. In a park with millions of human visitors and thousands of bears, that’s the only scalable strategy.

Field Notes From a Crowded Park

On a humid August evening near Elkmont, I watched a line of cars idle as a bear materialized at the edge of a meadow, then swivel away the instant someone cracked a cooler. The bear didn’t bolt; it recalculated, drifting toward cover where beetles and berries offered a quieter payoff. Moments like that make the science feel tangible: a split‑second decision tree built from memory, past encounters, and a precise read of the present. Bears aren’t scheming villains or cuddly neighbors; they’re expert generalists making the best of mixed signals we’ve scattered across their home. The Smokies show that when we simplify those signals – no trash access, no handouts, consistent rules – bears lean back into wild food and wild hours.

Conclusion

If you live in or visit the Smokies, the recipe is straightforward and powerful. Use certified bear‑resistant trash containers and actually latch them every time, store food and coolers inside a hard‑sided vehicle or cabin, and take down bird feeders when bears are active. Hike with distance in mind – at least 150 feet (about twice the length of a tennis court) – and carry bear spray where legal, knowing it’s a tool you’ll probably never need but will be glad to have. Report problem attractants and sightings to park staff so patterns can be mapped and addressed quickly. Most important, treat every bear encounter as a chance to reward good bear behavior by giving space and offering zero calories. In a place where learning rules the day and the night, our consistency is the cue that keeps bears wild.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.