They do not roar like hurricanes or crack like thunder, yet ocean currents quietly choreograph the world’s weather, steering heat, moisture, and entire ecosystems as if by an invisible hand. For decades, scientists chased a mystery: why do some regions heat up while others cool, even under the same rising greenhouse blanket? The solution, it turns out, rides in great ribbons of water that loop the globe from the surface to the abyss. These currents soften winters, sharpen monsoons, feed fisheries, and can tilt the odds of floods or droughts half a world away. Understanding them is no longer an academic puzzle – it’s a practical map to our near future.

The Hidden Clues

Here’s a jolt: the air you feel on a coastal walk today may have been tempered by water that began its journey decades ago in the far North Atlantic. Current lines leave fingerprints everywhere – bands of warm and cool water on satellite maps, narrow blooms of plankton visible from space, and fog banks that hug coastlines like a slow-moving tide. Fisherfolk read those clues for living, shifting to where cold upwelling teems with life, while sailors still treat the Gulf Stream as a moving highway. I once ferried across a narrow Atlantic shelf edge and felt the breeze turn oddly mild in minutes; a warm filament had slipped past us like a silent train.

These hidden signatures also shape our daily weather in quieter ways. A meandering current can nudge a storm track, altering when rain arrives and how long it lingers. Coastal cities learn it the hard way when currents slow and local sea level creeps higher against their seawalls. If you trace the detours, you find a story written in temperature, salt, and depth.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

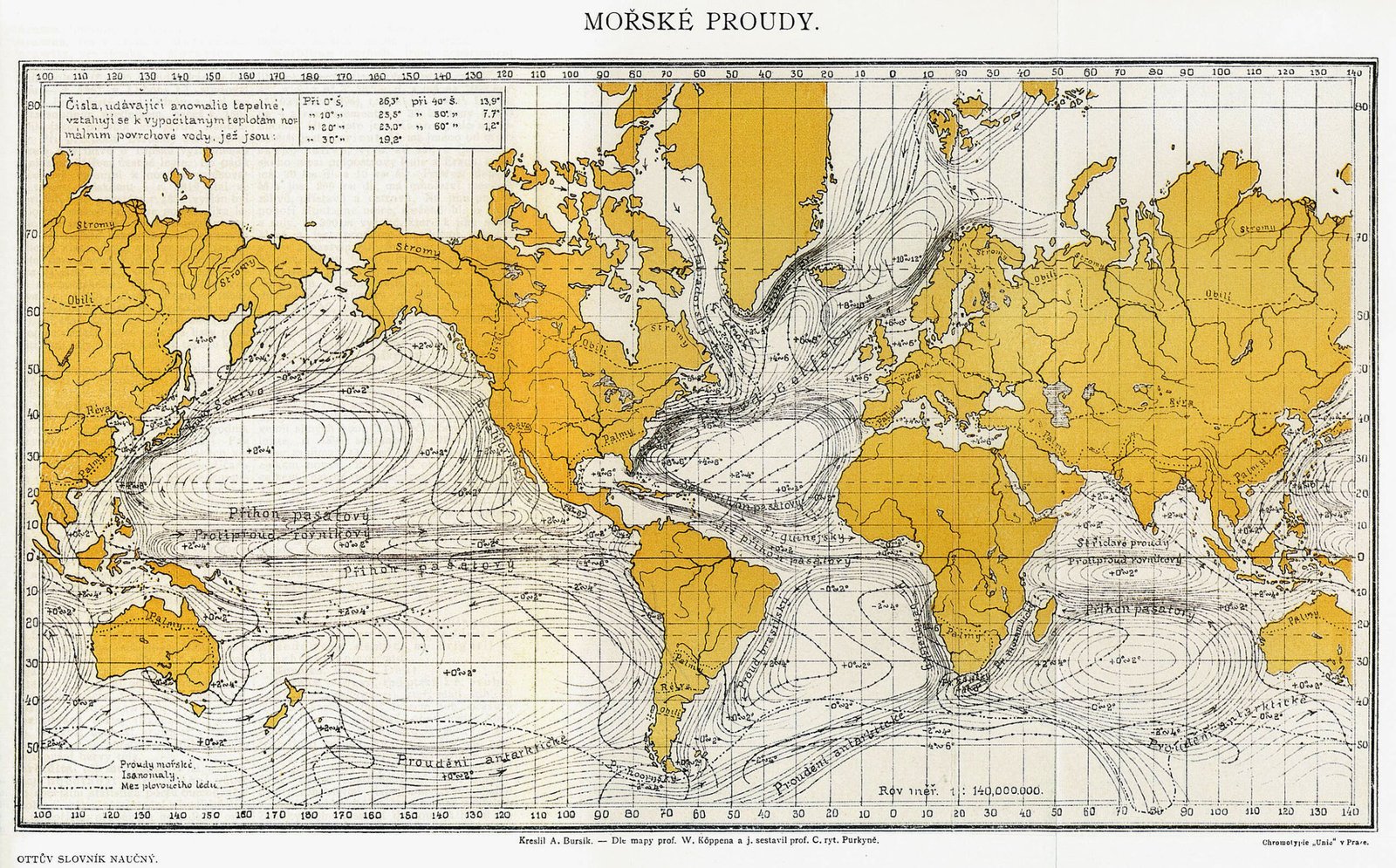

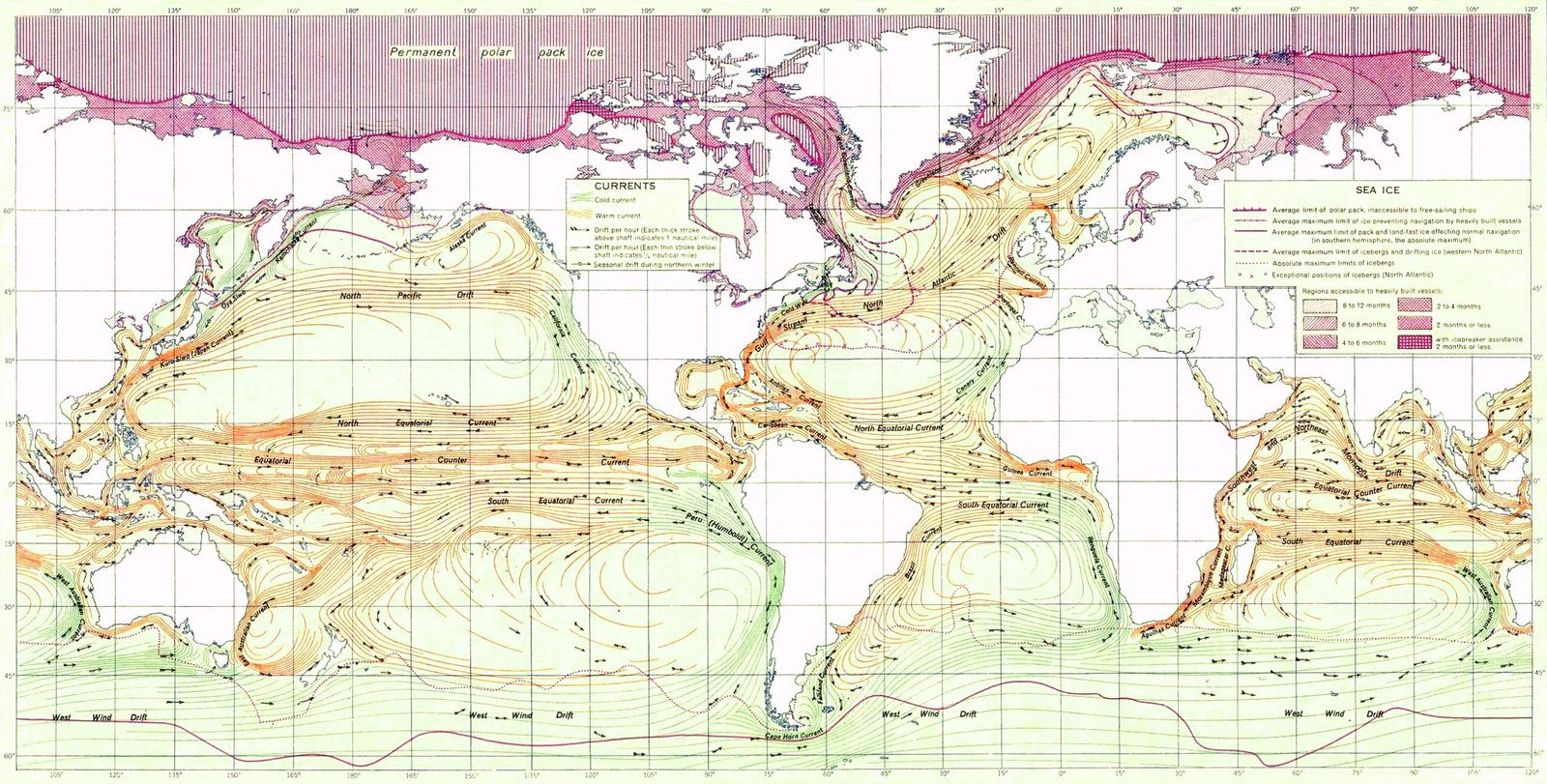

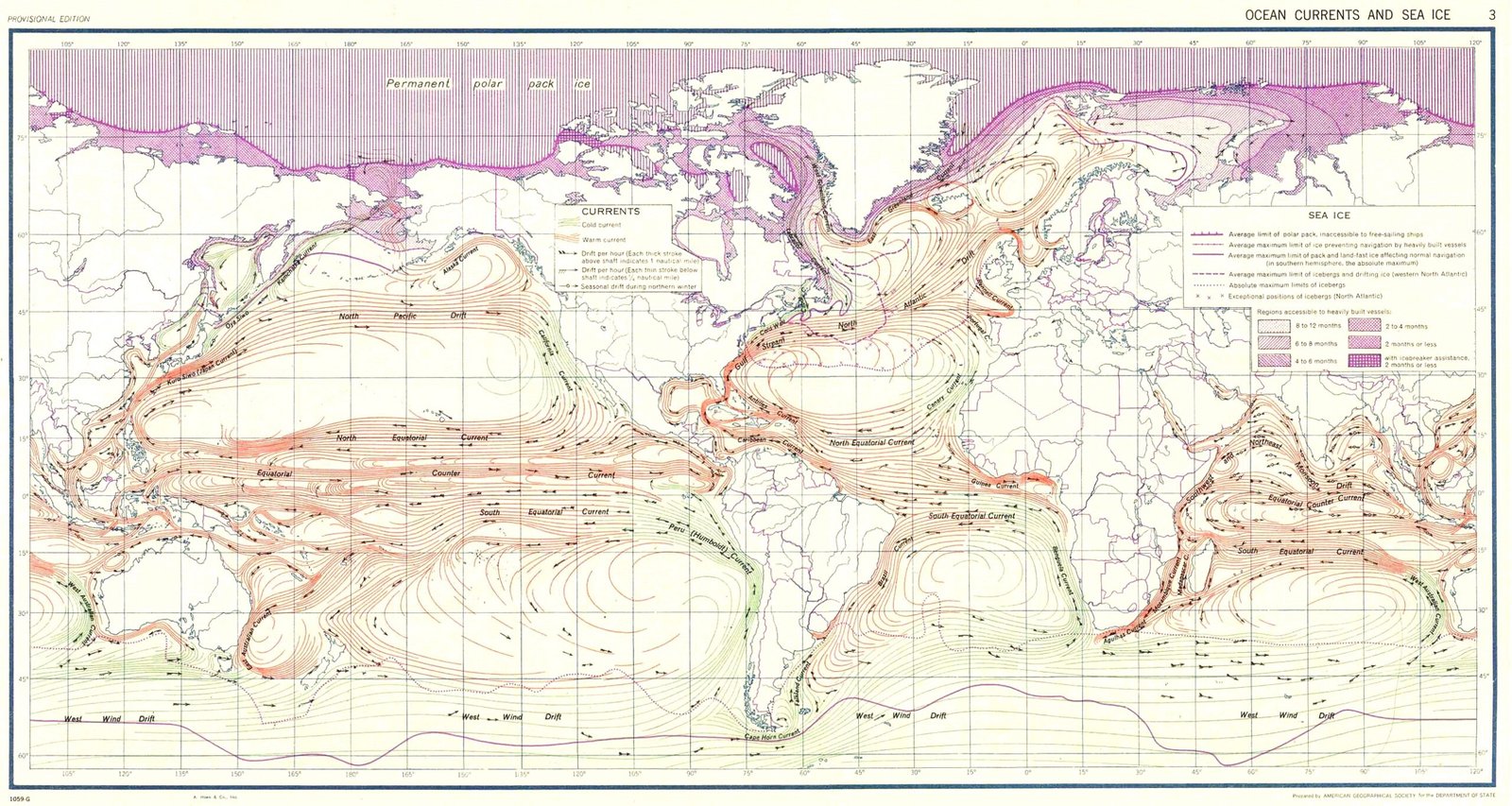

Long before satellites, Polynesian navigators read swell patterns and the feel of currents against a hull to cross vast ocean deserts. Centuries later, early chartmakers sketched the Gulf Stream by following drifting bottles and mail that arrived sooner than expected, a human-scale experiment in fluid mechanics. Today, the ocean is laced with autonomous floats that profile temperature and salinity from the sunlit surface to waters deeper than many mountains are tall. High above, satellites watch sea height and color, from which scientists infer current speed, eddies, and blooms.

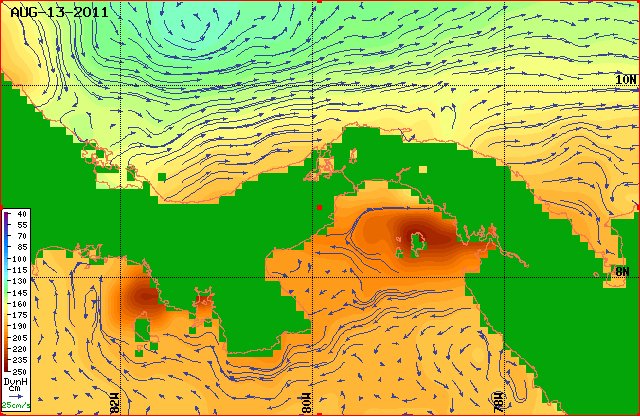

Fixed moorings now listen across entire basins, detecting the push and pull of major flow systems year after year. Taken together – floats, moorings, satellites, and ship surveys – they form a global nervous system that turns a once-murky picture into moving frames. The data are not perfect, especially in the harsh, ice-bitten south and the little-sampled abyss, but the resolution is getting sharper with every voyage and every launch.

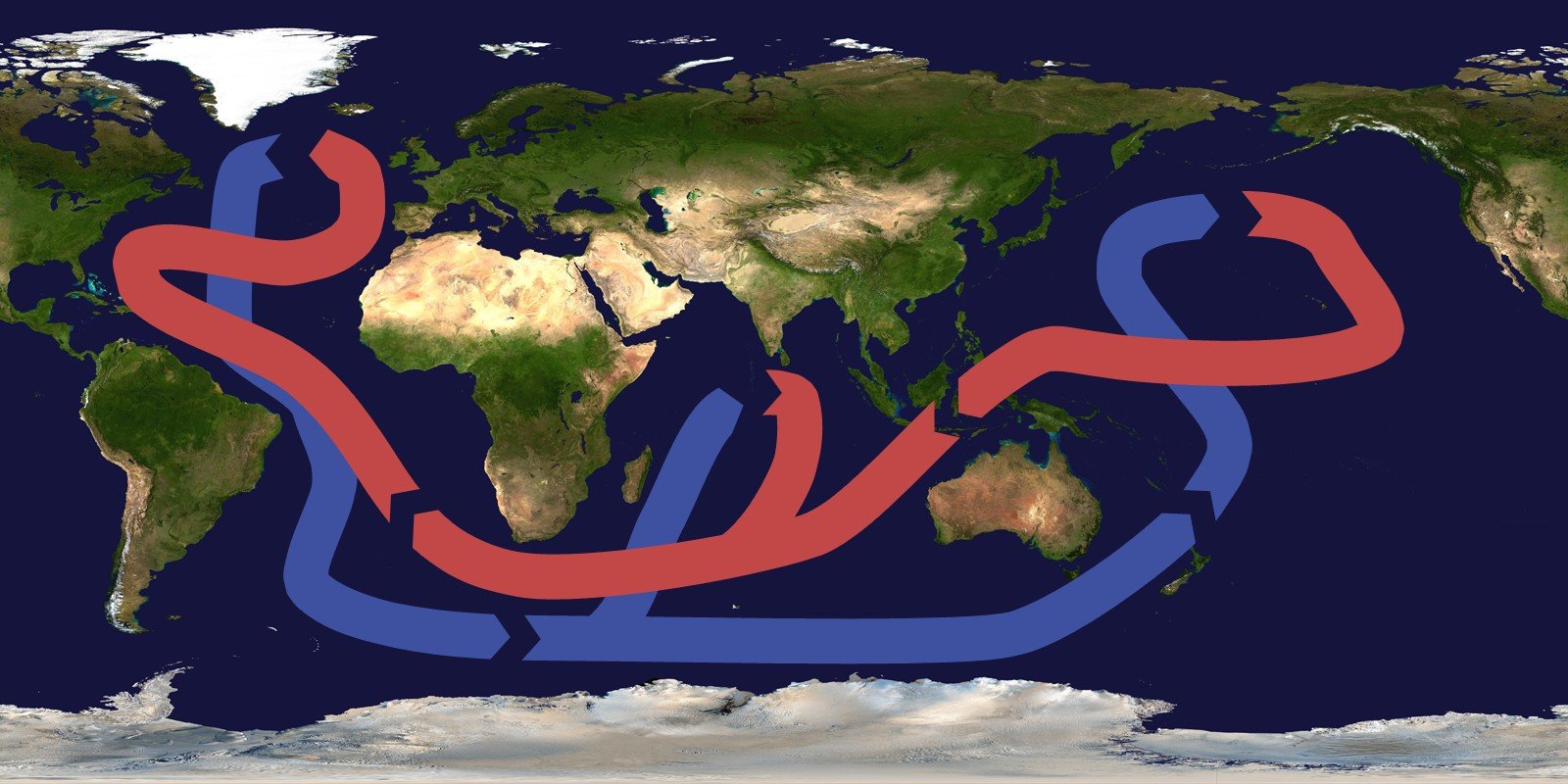

The Conveyor Beneath Our Feet

Beneath the chop of waves lies a planetary engine called the overturning circulation, knit together by temperature and salt. In the North Atlantic, surface waters cool, grow saltier through evaporation, and become dense enough to sink, sliding into the deep like a slow waterfall. Those waters drift southward along the ocean floor, eventually rising again in far-off upwelling zones where winds peel surface waters away and invite the deep to the light. This loop – often described as a conveyor belt – takes about 1,000 years to complete its full global cycle, though regional components may take years to decades.

It is not a single track but a braided river in three dimensions, with off-ramps that influence weather across continents. Similar processes around Antarctica feed the deepest layers of the world ocean, sending cold, oxygen-rich waters into trenches and basins. When these gears mesh smoothly, climates stabilize; when they grind or slip, the world notices.

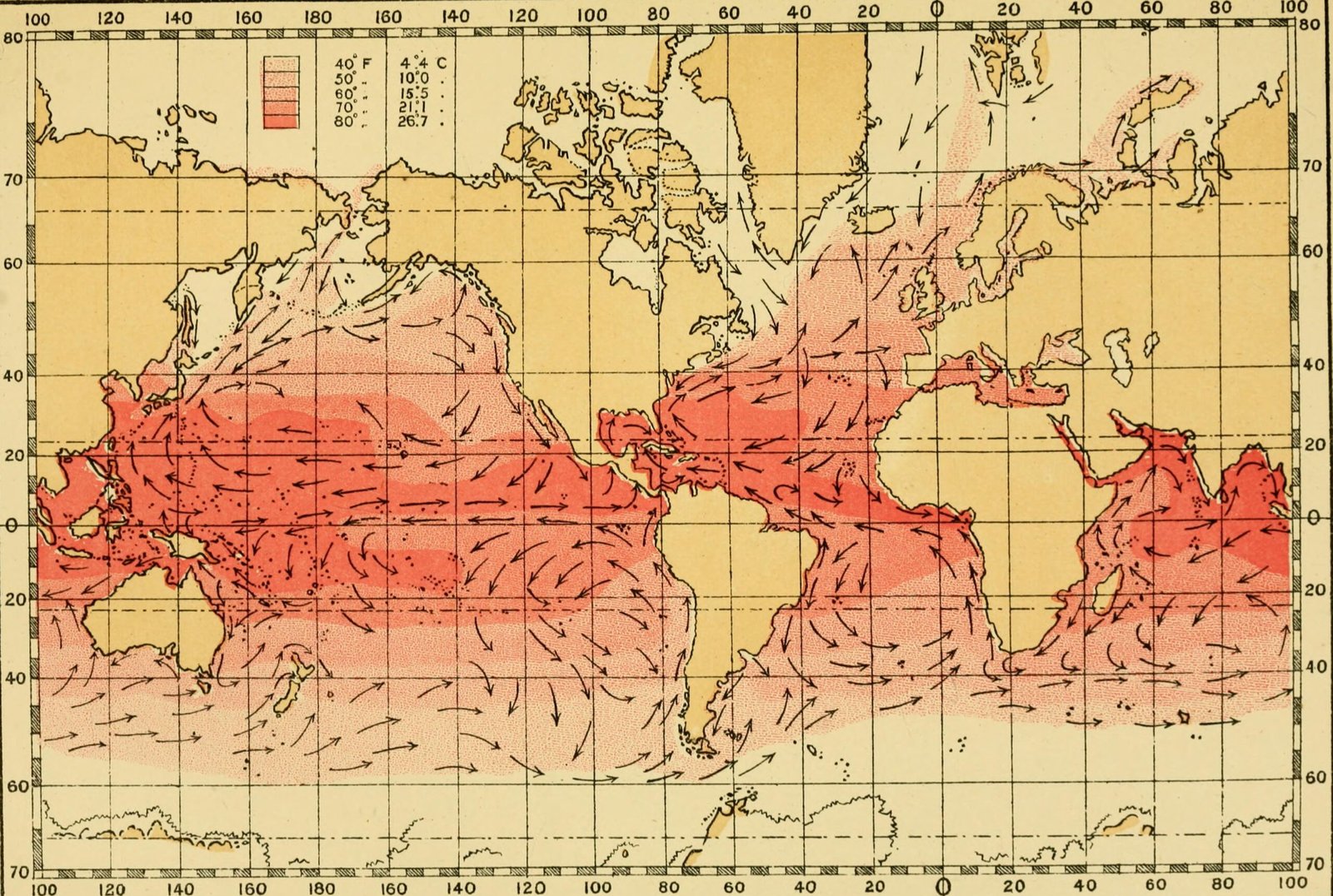

Heat Highways Across the Seas

Oceans absorb more than nine tenths of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases, and currents move that invisible cargo across the map. Western boundary currents – the Gulf Stream and Kuroshio among them – act like express lanes that shuttle warmth poleward, turning some coastlines mild and others storm-prone. When those lanes meander or shed eddies the size of cities, they can spark marine heatwaves that stress corals and shuffle fish populations. The energy does not vanish; it redistributes, changing when and where atmosphere and ocean trade heat.

Those trades matter for everything from snowfall in Europe to rainfall across East Asia and North America. A warmer ocean layer can insulate the atmosphere above, or it can fuel storms like a low flame under a pot. In a connected system, a nudge in one basin can ripple into the next, crossing the equator and bouncing off continents in long, slow waves.

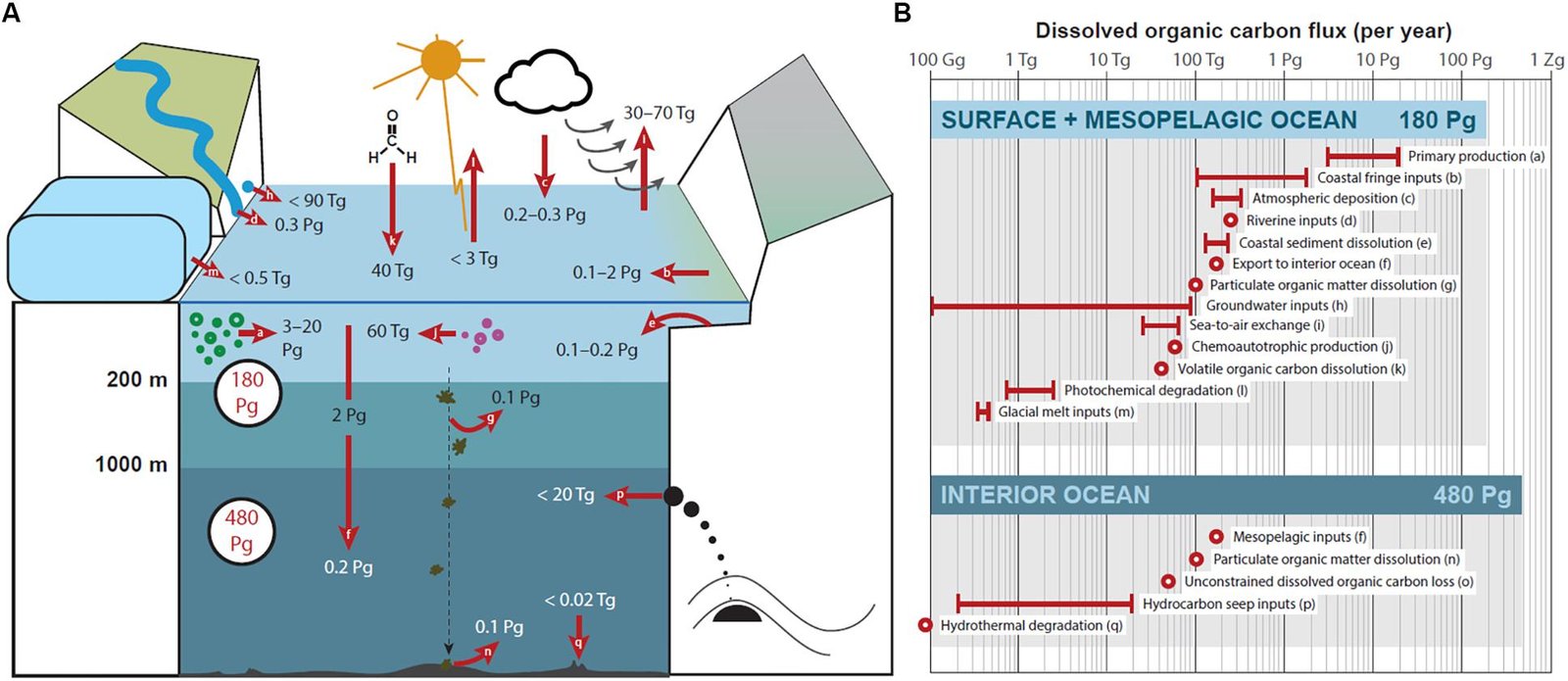

The Winds, The Water, The Carbon

Currents do more than haul heat; they help set the ocean’s role as a vast carbon sponge. In certain regions, winds draw surface waters away, and deep, nutrient-rich waters rise to replace them, boosting plankton blooms that lock carbon into shells and bodies. Some of that organic rain falls to depth and stays there for years to centuries, a quiet subsidy to climate stability. Elsewhere, especially near the equator and in strong upwelling zones, waters can release carbon back to the air as ancient, carbon-rich layers surface.

Whether the ocean is a net helper or a reluctant partner on any given year depends on how currents and winds align. Broadly, the seas take up roughly about one quarter of human-made carbon dioxide emissions, but that service is not guaranteed. If circulation patterns weaken or shift, the balance sheet can change in ways that affect both global warming and ocean chemistry.

Why It Matters

This is not just about physics drifting in the deep; it is about the daily fabric of risk and resilience. Currents can push warm water onto a coast and lift local sea level for months, raising the odds of nuisance floods even without a storm in sight. They can redirect storm tracks, making one season punishingly wet and the next startlingly dry, complicating farm decisions and reservoir plans. Fisheries ride these rhythms, with catches booming when upwelling is steady and collapsing when it falters.

Compared with forecasts that treat the ocean as a static backdrop, models that capture moving currents better anticipate heatwaves, marine blooms, and coastal hazards. They translate distant changes – like fresh meltwater in the far north – into local consequences. For insurers, city planners, and ship captains, that is the difference between steering by guesswork and navigating with a chart.

Global Perspectives

In the North Atlantic, the flow that carries warmth toward Europe shapes winters, sea ice margins, and even spring bloom timing. Around southern Africa, looping eddies can fling warm Indian Ocean waters into the Atlantic, with downstream effects on tropical storms and rainfall. Along the Pacific coast of the Americas, the Humboldt and California currents cool coastal air and feed immense fisheries, linking plankton to seabirds to livelihoods in a single, fragile chain.

Across the Indian Ocean, monsoon rains respond to sea temperature contrasts sculpted by currents and seasonal winds. In the Arctic, a wind-driven gyre can trap freshwater like a coiled spring; when it releases, it can freshen downstream seas and tweak circulation. Each region writes its own chapter, but the plot is shared: moving water resets the climate stage.

The Future Landscape

The hardest questions now target the pace and pattern of change. Freshwater from ice melt and rainfall can make northern seas lighter, potentially slowing parts of the overturning circulation and reshuffling storm belts. Stronger winds around Antarctica may stir more deep water upward, altering how heat and carbon are stored, with consequences that unfold over decades. Regional currents may intensify or wander, sharpening the risk of marine heatwaves in some places and unexpected chills in others.

New tools are racing to keep up: deep-diving floats that roam the abyss, nimble gliders that slice through fronts, and satellites that measure sea height with hair-width precision. Even so, the deep ocean remains under-sampled, and models still struggle to resolve eddies that do outsized work. The stakes are high, not for a single year, but for the reliability of coastlines, food systems, and infrastructure built to last a lifetime.

Conclusion

Ocean currents are not background scenery; they are the stage crew, the lighting, and half the script for Earth’s climate play. They carry yesterday’s heat into tomorrow’s weather, braid life across basins, and quietly set the odds for extremes. The more we observe and understand them, the less the future feels like a coin toss and the more it becomes a map we can read. I’m convinced that paying attention to these flows is one of the smartest climate moves we can make – calm, practical, and profoundly effective.

Stand on any shore, feel the breeze, and remember there’s a river moving beneath your feet, shaping the air on your skin and the storm on the horizon. Where will that river take us next – are you watching for the turn?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.