A speckled shadow slips across a rocky ridge at dusk, then vanishes into oak woodland before your eyes adjust. For decades, the jaguar was more legend than neighbor in Arizona, a ghost of the borderlands that seemed to exist only in grainy photos and old field notes. Now, a new wave of evidence is rewriting that story and raising a thrilling, complicated question: are these big cats truly returning, or are we merely catching better glimpses of rare wanderers? Scientists and ranchers, hikers and tribal land stewards, all find themselves part of the same unfolding mystery. What we know is growing fast, but what it means for the future of the Southwest is even more electrifying.

The Hidden Clues

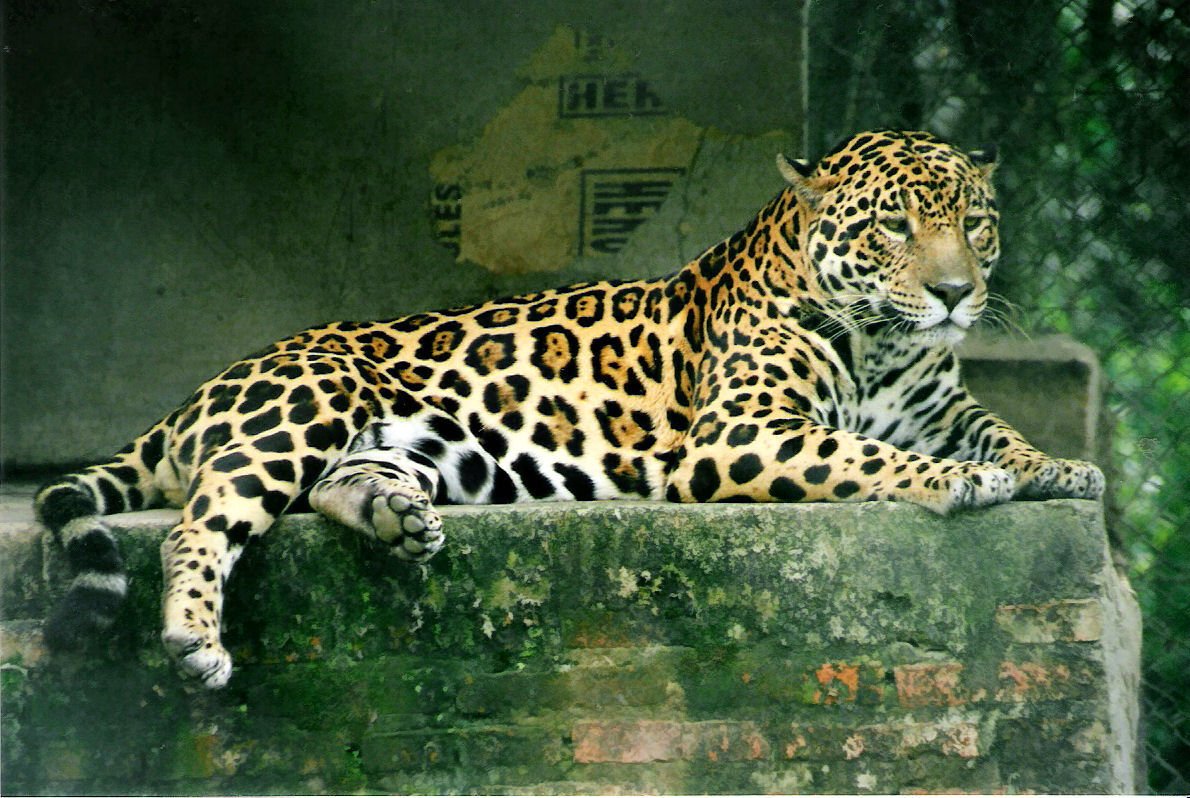

Jaguars are masters of being unseen, so the first signs rarely roar; they whisper. A single rosette-marked flank on a trail-camera frame, a paw print where a creek braids through sycamores, scat tucked under manzanita – each is a breadcrumb on a sprawling map. Field biologists stitch these clues into individual identities using rosette patterns, the way a detective might match fingerprints. I’ve stood beside one of those cameras on a hot afternoon, feeling silly for talking in a whisper, yet convinced the hills were listening. The camera clicked to the wind, and that small sound felt like a promise.

Teams now layer those images with time stamps, elevation, and weather, building behavioral profiles for cats that most people will never see. Small evidence adds up to big patterns: preferred ridgelines, favored water sources, and seasonal movement corridors that repeat year after year. The quiet data, not the dramatic sighting, is what’s changing minds.

From Ancient Tracks to Modern Science

Long before camera traps, Indigenous knowledge and early naturalists documented jaguars along rivers and in the Sky Islands, those mountain ranges that rise like green ships from desert seas. Today, that tradition meets modern forensics: DNA extracted from scat confirms species and sometimes relatedness, and software compares rosette patterns with uncanny precision. Satellite collars remain rare for jaguars in this region, but lightweight GPS units and refined capture protocols are on the table, guided by strict ethics to minimize stress. Drones help map vegetation after wildfires, highlighting regrowth that may draw deer and, eventually, their predators. Science is not replacing old ways of knowing so much as translating them into data we can test, share, and act on.

Crucially, agencies and nonprofits standardize photo archives so cross-border images can be matched, ensuring a cat seen in Sonora can be recognized weeks later on an Arizona hillside. That binational stitching is the difference between a one-off encounter and a scientifically grounded story of return.

The Borderland Corridor

Arizona’s southern mountains – Patagonia, Huachuca, Santa Rita, Chiricahua – form stepping stones that connect with jaguar habitat in northern Sonora. These ranges offer cooler microclimates, dense cover, and water, a triad that big cats track like a survival algorithm. Physical barriers complicate that puzzle, channeling wildlife into fewer crossings and raising the stakes for each remaining canyon and wash. Where open lands and low fencing persist, cameras catch a surprising parade: deer, coatis, black bears, mountain lions, and, now and then, the cat everyone hopes for.

Connectivity is not just geography; it’s timing. Seasonal rains transform dry arroyos into travel lanes, and nighttime quiet turns ranch roads into corridors. Conservation work therefore focuses on precise bottlenecks where a hundred small decisions – gate placement, staffing at crossings, riparian restoration – can make or break a jaguar’s path.

Prey, Water, and Fire

Follow the prey and you’ll find the predator. Jaguars in the borderlands move with herds of white-tailed deer and javelina, but they also key in on rugged cover and reliable water. In dry years, a single seep or stock tank can shape movement like a magnet, concentrating life and risk in the same spot. Wildfire adds another twist: severe burns can strip shade and ambush cover, but mosaics of low-intensity fire can open understory and boost forage for deer.

Land stewards now plan for jaguars indirectly by managing prey and water at landscape scales. Strategic tank maintenance, riparian fencing to let willows recover, and post-fire reseeding all ripple up the food chain. The cat benefits precisely because everything else does.

Climate Crossroads

As the Southwest warms, the logic of latitude starts to blur. Cooler, wetter refuges climb the mountains, and species that once skirted the border now find suitable pockets farther north. That does not guarantee a thriving jaguar population in Arizona; it simply increases the odds that wandering males will explore and linger. Climate models project more weather whiplash – longer dry spells punctuated by intense storms – which can both create and destroy habitat windows.

In this moving target, resilience hinges on variety: a patchwork of oak woodland, pine forest, desert grassland, and riparian shade spread across elevations like rungs on a ladder. If the ladder’s intact, jaguars can climb it as conditions allow. If we knock out the rungs, the science becomes irrelevant.

Why It Matters

The return of a top predator is not just a feel-good story; it’s a test of our ecological literacy. Jaguars exert a quiet pressure that cascades through prey behavior, vegetation, and even water quality, the same way a keystone supports an arch. Their presence tells us that the food web is strong enough to support the heaviest weight nature puts on it. It also challenges us to blend ranching livelihoods, tribal sovereignty, recreation, and conservation without pitting neighbors against one another.

Compared with past approaches focused on single-species fixes, today’s work treats the landscape as a living network. Rather than fencing nature into islands, managers emphasize coexistence tools – night corrals, carcass removal, quick response to depredation – so conflict does not spiral. The measure of success is subtle: fewer crises, steadier herds, and a big cat that passes by unseen because it has no reason to linger near people.

Global Perspectives

Arizona’s jaguar story is a border chapter in a continental biography. South through Mexico and Central America, conservationists have carved out a tapestry of reserves, wildlife-friendly ranches, and corridors that keep populations connected. Those efforts gain power when they sync with work in the north, because genetic exchange keeps small populations from blinking out. The lesson echoes from the Sonoran thornscrub to the Amazon: link habitats, reward coexistence, and the system can hold.

What makes the borderlands especially compelling is the collision of high-tech monitoring with community pragmatism. A rancher’s decision to pen calves at night can matter as much as any algorithm. When the two align – data pointing to a risk hot spot, local knowledge offering a precise fix – the result feels less like compromise and more like craft.

The Future Landscape

Emerging tools could tip the balance from chance encounters to intentional stewardship. Camera networks now feed into AI systems that flag unique rosette patterns in near real time, helping biologists respond quickly when a cat appears. Environmental DNA from water samples can detect rare species without a single photograph, a game-changer in places too rugged for cameras. Habitat models, updated with fire maps and drought indicators, can forecast where corridors are likely to open or close in the next season.

The challenges are equally modern: maintaining cross-border data sharing, designing wildlife-permeable infrastructure, and funding long-term monitoring rather than one-off studies. Success may not look like a resident breeding population tomorrow; it may look like steady, low-drama movement across the landscape over many years. Patience, in other words, is a conservation tool too.

How You Can Help

Big cats run on small acts. If you live or recreate in southern Arizona, report credible wildlife observations to state agencies and respect closures in post-fire zones so habitats can recover. Support ranchers and tribes implementing coexistence practices; the cheapest conflict is the one prevented. Choose community science projects that maintain data privacy and follow ethical guidelines, because bad data can put animals and people at risk.

For anyone farther afield, back organizations restoring riparian corridors, advancing cross-border research, and training rapid-response teams for depredation events. And when you hike, drive, or vote, remember that connectivity is a thousand ordinary decisions made in the same direction.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.