For millions of years, our planet has danced between extremes – from frozen wastelands where massive ice sheets stretched across entire continents, to warm periods like today where life flourishes in temperate climates. This dramatic climate choreography isn’t random chaos, but follows predictable patterns that scientists have only recently begun to decode. The story of Earth’s ice ages reveals cosmic cycles, feedback loops, and climate triggers that make our planet’s past both fascinating and surprisingly predictable.

The Cosmic Clock That Controls Our Climate

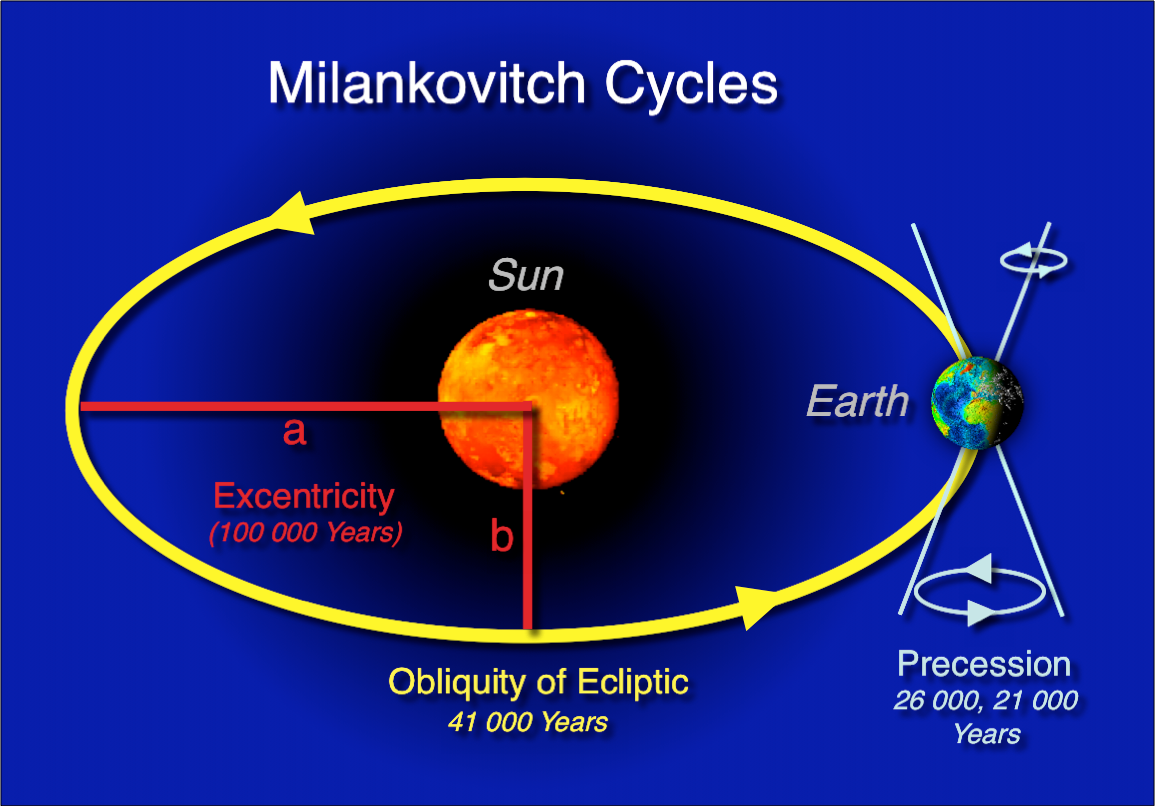

Earth’s position and orientation in space changes over thousands of years in three distinct ways, creating what scientists call Milankovitch cycles, which describe the collective effects of changes in the Earth’s movements on its climate over thousands of years, named after Serbian geophysicist and astronomer Milutin Milanković who provided definitive analysis in the 1920s. Think of it like a cosmic metronome that sets the rhythm for our planet’s climate changes.

The shape of Earth’s orbit around the Sun changes from less to more and back to less elliptical in about 100,000 years, while Earth’s tilt changes from 21.5° to 24.5° and back again in about 41,000 years, and Earth’s axis wobbles with a period of about 19,000 to 26,000 years. These seemingly small orbital variations create massive impacts on how much solar energy reaches different parts of our planet throughout the year.

How Tiny Changes Trigger Massive Ice Sheets

The beauty of Milankovitch cycles lies in their subtlety and power. These cycles do not change the total amount of solar energy Earth receives over time, but they redistribute it affecting how much sunlight reaches different parts of the planet and at what time of year, with these subtle shifts in solar radiation being enough to tip Earth’s climate toward either warming or cooling over thousands of years. It’s like adjusting the thermostat by just a degree, but doing it for thousands of years.

The most significant factor for triggering ice ages is the amount of summer solar radiation at high latitudes, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, and these cycles act as a climate trigger, setting off larger feedback mechanisms such as changes in carbon dioxide levels, ice-albedo effects, and ocean circulation patterns. Once the process begins, Earth’s climate system amplifies these small changes into dramatic transformations.

The Million-Year Pattern Scientists Just Cracked

For decades, researchers struggled to match ice ages with orbital patterns, but recent breakthroughs have revealed something remarkable. Scientists found that each glaciation of the past 900,000 years follows a predictable pattern, with researchers able to make accurate predictions of when each interglacial period would occur and how long each would last, confirming that natural climate change cycles over tens of thousands of years are largely predictable and not random or chaotic.

Deep-sea sediment cores found that Milankovitch cycles correspond with periods of major climate change over the past 450,000 years, with Ice Ages occurring when Earth was undergoing different stages of orbital variation, and several other projects using ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica have provided strong evidence of these cycles going back many hundreds of thousands of years. This discovery represents one of the most significant advances in understanding Earth’s long-term climate behavior.

When the Last Ice Age Gripped Our Planet

The Last Glacial Maximum occurred between 26,000 and 20,000 years ago when ice sheets were at their greatest extent, covering much of Northern North America, Northern Europe, and Asia and profoundly affecting Earth’s climate by causing a major expansion of deserts along with a large drop in sea levels. Imagine a world where nearly one-third of all land was buried under ice sheets sometimes miles thick.

The average global temperature about 21,000 years ago was about 6°C colder than today, with permanent summer ice covering about 8 percent of Earth’s surface and 25 percent of the land area, while sea levels were approximately 125 metres lower than present day. This wasn’t just a cold snap – it was a fundamentally different planet where massive ice sheets stretched from the Arctic to the middle latitudes, reshaping continents and redirecting ocean currents.

The Mystery Switch That Changed Everything

One of the most puzzling aspects of Earth’s ice age history involves a dramatic shift that occurred roughly one million years ago. This shift is called the Mid-Pleistocene Transition, where before this point cycles between glacial and interglacial periods happened every 41,000 years, but after, glacial periods became more intense and lasted 100,000 years, giving Earth the regular ice age cycles that have persisted into human time.

Scientists believe that prior to this transition, ice sheets began to stick to their bedrock more effectively, causing glaciers to become thicker than before, leading to greater global cooling and disruption of ocean circulation, with these changes resulting in stronger ice ages and the ice-age cycle shift, supporting the hypothesis that gradual removal of slippery continental soils allowed ice sheets to cling more tightly to crystalline bedrock beneath. This discovery shows how Earth’s surface itself evolved to enable more dramatic ice ages.

The Carbon Dioxide Connection

Ice ages aren’t just about cold temperatures – they involve a complex dance between ice, oceans, and atmosphere that amplifies small orbital changes into massive climate shifts. Changes in orbital cycles do not immediately cause rises or falls in atmospheric CO2, but initial increases in ice cover trigger feedbacks that cause atmospheric CO2 to fall at the start of ice ages through multiple pathways.

As ice sheets grow, sea levels change dramatically, falling around 120 meters and exposing large areas of land that allow growing vegetation to take up more CO2, while colder ocean water dissolves more CO2 from the atmosphere, and ice-age glaciers grind up rocks into dust that provides nutrients to ocean life, helping boost carbon storage in the deep ocean. This creates a powerful feedback loop that amplifies the initial cooling trigger.

What Actually Ends an Ice Age

The melting of massive ice sheets represents one of the most dramatic climate transformations our planet experiences. Changes in orbital cycles trigger initial melting of ice sheets in the northern hemisphere, causing large amounts of freshwater to pour into oceans and disrupt Atlantic circulation, which cools the northern hemisphere and warms the southern hemisphere, causing ocean releases of CO2 that warm the entire planet, with the vast majority of global warming at the end of ice ages occurring after CO2 increased.

Roughly 20,000 years ago great ice sheets stopped their advance, and within a few hundred years sea levels had risen by as much as 10 meters, with this freshwater flood shutting down ocean currents and warming Antarctic regions instead, changing circumpolar winds and causing Southern Ocean waters to release carbon dioxide equivalent to the rise in atmospheric CO2 over the last 200 years. The process shows how local changes can cascade into global transformations.

The Little Ice Age That Wasn’t Really an Ice Age

Not all cold periods qualify as true ice ages. The Little Ice Age was a multi-centennial period of relatively low temperature beginning around the 15th century, with mean annual temperatures declining by about 0.6°C below long-term averages between 1450 and 1850, representing only a modest cooling of the Northern Hemisphere of less than 1°C relative to late twentieth century levels.

While evidence shows increased glaciation in regions including Alaska, New Zealand and Patagonia, the timing of maximum glacial advances differs considerably across regions, suggesting largely independent regional climate changes rather than globally-synchronous increased glaciation, leading scientists to conclude that terms like “Little Ice Age” have limited utility in describing global temperature changes. This demonstrates the difference between regional cooling and true ice age conditions.

The Next Ice Age is Coming – But When

Recent scientific breakthroughs have enabled researchers to predict when Earth’s next ice age would naturally begin. Natural patterns suggest that we should currently be in the middle of a stable interglacial period and that the next ice age would begin approximately 10,000 years from now, with this prediction based on new analysis suggesting the onset could be expected in 10,000 years’ time.

More research is needed to pin down precise timings, but ice sheets would likely start expanding in around 10,000 to 11,000 years and reach their maximum extent within the following 80,000 to 90,000 years, then take another 10,000 years to retreat to the poles. However, this natural timeline assumes Earth’s climate follows its historical patterns without human interference.

How Human Activity Changed the Game

The most startling revelation about Earth’s next ice age is that human activity has likely derailed the entire natural cycle. Humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions may have radically shifted the climate’s trajectory, with human emissions of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere having already diverted the climate from its natural course, making a transition to a glacial state in 10,000 years’ time very unlikely because of longer-term impacts into the future.

There is much debate around the timing of the next glaciation, but most experts agree that humans are disrupting these cycles through global warming, with high CO2 levels preventing new glaciation, and with carbon dioxide levels now at their highest in at least 800,000 years, the natural timeline has shifted dramatically. We’ve essentially put Earth’s natural ice age cycle on hold.

Could Global Warming Actually Trigger an Ice Age

In a surprising twist, some scientists suggest that current warming could eventually lead to cooling. With modern human activity adding vast amounts of CO2, a hotter planet will continue in the near future, but models predict another cooling overshoot caused by warming could follow, though it would be less severe than ancient ice ages, with higher oxygen levels today dampening the effect, but this could still accelerate the arrival of the next ice age.

Currently, huge volumes of fresh water are being poured into the North Atlantic by melting glaciers, disrupting ocean currents like the Gulf Stream, with recent studies indicating that cold water outflow has dropped by 20 percent since 1950 and northern waters have become progressively less saline, potentially bringing dramatic climate change to the entire planet. This scenario could create regional cooling even during global warming.

Lessons from Earth’s Frozen Past

Understanding ice ages provides crucial insights into how Earth’s climate system responds to changes. Ice core data from Antarctica and Greenland show clear correlation between temperature, CO2 levels, and Milankovitch cycles over the last 800,000 years, while sediment records from deep-sea cores reveal layers that align with predicted cycles, and glacial deposits on land match the expected timing of glaciations and interglacial periods.

By understanding these natural cycles, scientists gain crucial context for evaluating how human activities are reshaping Earth’s climate system, with findings revealing a predictable system where future climate can be forecast based on orbital mechanics alone in a world without human-caused climate change. This knowledge helps us understand both our planet’s past and the unprecedented nature of current changes.

Conclusion

The story of Earth’s ice ages reveals a planet governed by cosmic rhythms, where tiny changes in our orbit around the sun trigger massive transformations that reshape continents and redirect ocean currents. For nearly a million years, these cycles have operated like clockwork, creating predictable patterns of warming and cooling that scientists can now forecast with remarkable accuracy.

Yet humanity has fundamentally altered this ancient dance. Our greenhouse gas emissions have likely postponed the next natural ice age by thousands of years, creating an unprecedented experiment with our planet’s climate system. While we’ve avoided the deep freeze that would naturally arrive in 10,000 years, we’ve traded predictable natural cycles for uncharted territory. The same forces that once buried much of North America and Europe under miles of ice continue to operate, but now they must compete with human influence on a scale never before seen in Earth’s history.

What will win out in the end – the cosmic cycles that have governed our climate for millions of years, or the rapid changes we’re making to our atmosphere right now?