Picture a mind tuned to echoes, a brain that reads the sea like a living library. For decades, scientists have wondered whether dolphins, with their complex social lives and acoustic wizardry, might illuminate how intelligence evolves. The mystery is irresistible: two very different bodies – flippers versus hands – yet striking overlaps in curiosity, play, and problem‑solving. The real story isn’t whether dolphins think like us, but how their very different path to smarts can sharpen our picture of what intelligence really is. And as ocean noise rises and habitats shift, the race to understand them has never felt more urgent.

The Hidden Clues

What if the sharpest mirrors of our own minds are cruising under whitecaps, keeping pace with our boats? Dolphins pass the “mirror test” of self-recognition, navigate elaborate alliances, and seem to assign each other identity through unique signature whistles. When I first watched a wild bottlenose surf a bow wave off Florida, it wasn’t just spectacle – it felt like meeting a mind that was busy, aware, and possibly curious about me. Those small, electric moments are the breadcrumbs that keep researchers returning to sea. They suggest intelligence isn’t a single ladder but a braided river with many channels.

Hidden clues also live in their flexibility. Dolphins can switch hunting strategies with the tide, improvise around human gear, and coordinate with astonishing timing. Such fluid behavior hints at foresight and learning, not just reflex. If intelligence is the art of adapting under uncertainty, dolphins paint with a bold brush.

Brains Beyond Size

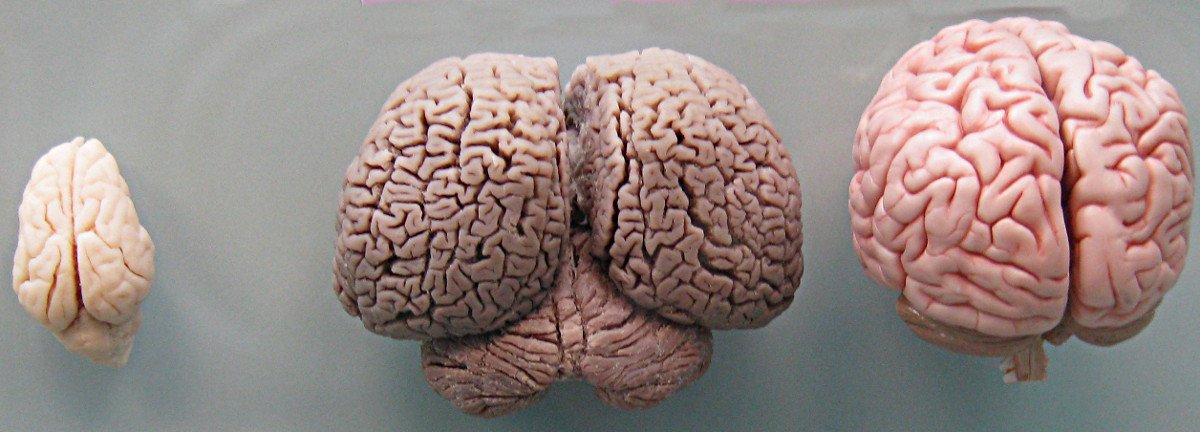

Dolphins carry big, elaborately folded brains relative to their body size, a hallmark that correlates in many mammals with complex cognition. But it’s not a simple numbers game; different species pack neurons and connect regions in different ways. Auditory pathways are particularly developed, fitting a life built around sound, while association areas knit signals into meaning. The result is a neural architecture optimized for the ocean’s dim, echoing world, rather than our light‑driven landscape. That divergence is precisely why comparisons are powerful.

Think of human and dolphin brains as two engines tuned for different tracks. Our visual cortex hums; theirs turns acoustic time into three‑dimensional space. When both reach sophisticated problem‑solving from opposite directions, it signals that intelligence is not a human blueprint – it’s a design space with multiple workable solutions. That’s a revelation for neuroscience and for AI.

Language in the Waves

Dolphins don’t “speak” like we do, but their communication system is rich, layered, and social to the core. Signature whistles function like names that individuals recognize even after long separations, and the animals can mimic or address those identifiers. Beyond whistles, they use clicks and burst pulses that vary with context, from foraging to social play. Sequences of sounds can carry nuanced information, and the timing within groups often looks remarkably coordinated. It’s less a single code than a toolkit of acoustic behaviors.

Researchers now pair hydrophone arrays with machine learning to tease out patterns once buried in noise. Early signals suggest combinations and rules, though not full human‑style grammar. The takeaway is sober and thrilling at once: dolphin communication is sophisticated, but probably different in fundamentals from language. That difference shines a light on which parts of communication are universal and which are uniquely human.

Culture and Learning

Culture isn’t reserved for primates. In some populations, dolphins pass along foraging traditions – like wearing sea sponges over the snout to protect it while probing the seafloor – that spread along family lines. Elsewhere, coordinated mud‑ring feeding or strand feeding appears taught, not hardwired. These are regional “accents” of behavior, maintained by social learning rather than genes. Watching such customs persist across generations is like seeing the ocean write its own footnotes.

Social life itself demands mental muscle. Tracking allies and rivals, negotiating babysitting, and timing cooperative hunts are tasks that reward memory and inference. When knowledge flows along matrilines or male alliances, it becomes a cultural scaffold. Culture, in turn, can pull cognition higher – the way a gym pulls muscle. That feedback loop is a central clue to how complex minds evolve.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Humans built stone tools; dolphins built traditions – different routes to the same destination of problem‑solving. Today, our tools turn toward the sea: multi‑element hydrophone arrays, autonomous gliders, and high‑resolution tags that log heartbeats, dives, and soundscapes. With them, researchers reconstruct the sensory world from a dolphin’s viewpoint – what it hears, how it maneuvers, when it chooses to rest or sprint. It’s like switching from a blurry shoreline photo to a live drone feed. The data is finally catching up to the questions.

Even lab work is changing. Cross‑modal tasks test whether dolphins can match a sound to an object they saw earlier, probing memory and abstraction. Carefully designed uncertainty tasks explore whether they “know what they don’t know,” a hallmark of metacognition. Each experiment chips away at our land‑locked assumptions, turning anecdotes into evidence. That shift – from stories to statistics – marks a scientific coming of age.

Inside the Dolphin Mind

Dolphins ace delayed matching tasks, follow human gestures, and improvise cooperative problem‑solving, all without hands or tools. They appear to plan around constraints in their watery world, using social partners like extra limbs. Unihemispheric sleep – resting one brain hemisphere at a time – keeps them alert to predators and calves while still consolidating memory. These are clever trade‑offs, not magic tricks. Adaptation writes the rules; dolphins read them fluently.

What about consciousness? We should be cautious, but patterns of self‑directed behavior, flexible learning, and social sensitivity keep nudging the discussion forward. Their minds may be differently organized yet similarly capable in certain domains, especially social reasoning and acoustic modeling. The point isn’t to crown a rival to humans – it’s to map the many peaks of cognition. Dolphins occupy one of the tallest.

Why It Matters

How we define intelligence shapes how we teach children, design AI, and protect wildlife. If dolphins achieve sophisticated cognition without hands, fire, or writing, then intelligence is broader than our tool‑centric lens allows. Comparing species that solved life through sound rather than sight exposes which mental skills are universal – like pattern recognition – and which are cultural add‑ons. It also reframes conservation: destroying acoustic habitats doesn’t just remove food, it erases information. In an information economy of the sea, noise is a tax.

Consider the stakes in plain terms:

- Chronic ocean noise can mask signals over distances that once connected groups.

- Entanglement and bycatch disrupt social networks that transmit learned skills.

- Habitat loss removes the classrooms where young dolphins practice foraging traditions.

Protecting minds means protecting the mediums those minds use to think – water quality, prey webs, and especially quiet.

Global Perspectives

Dolphins aren’t a single story. Coastal bottlenose living in seagrass channels face different cognitive pressures than open‑ocean species surfing swell lines. Orcas, the largest dolphins, develop hunting cultures so distinct that biologists recognize ecotypes by diet and dialect. River dolphins wrestle with murky currents and human traffic, a world where echolocation becomes both lifeline and liability. Each environment pushes on perception and problem‑solving in its own way.

Local communities hold crucial knowledge, too. Fishers can describe seasonal movements; indigenous observers often track behavior across lifetimes. When that knowledge meets rigorous field methods, science accelerates. The global picture becomes a mosaic rather than a headline. And mosaics resist simple answers.

The Future Landscape

Next‑generation tags will sync heartbeat, brain‑adjacent signals, motion, and sound to show how decisions unfold second by second. Passive acoustic networks, powered by efficient edge AI, could map communication across entire bays without constant human presence. Better source‑separation will disentangle overlapping whistles, while causal models test whether sound patterns truly predict behavior. The frontier is less about bigger datasets and more about smarter questions. What counts as a concept for a dolphin, and how would we know?

Challenges loom. Data must be ethically gathered, with minimal disturbance and tight privacy for animals frequently photographed and tracked. Models need guardrails against anthropomorphism and overfitting. And we’ll have to accept that some comparisons to human language or consciousness may remain unresolved. Uncertainty isn’t failure – it’s an honest boundary that keeps science sharp.

What We Still Don’t Know

We still lack a full map of dolphin neural micro‑circuits and how they scale across species. We don’t know how cultural traditions survive shocks like mass strandings or rapid prey shifts. We can describe signature whistles, but we’re only beginning to test the rules that govern their sequences. Even cooperation, so visible at the surface, hides subtleties of negotiation and trust. Big, charismatic behaviors can distract from the quieter mechanisms underneath.

That’s a feature, not a flaw. Science advances by turning mysteries into measurements, then into new mysteries. Each careful null result is as valuable as a splashy finding, steering us away from catchy myths. The work takes patience, better tools, and humility. The sea rewards all three.

How You Can Help

You don’t need a research vessel to make a difference. Support coastal protections that reduce noise and runoff, because clean, quiet water is the classroom where dolphin culture thrives. Choose seafood from responsible fisheries to cut bycatch that fractures social groups. If you boat, slow near feeding or nursery areas and give animals room to move and communicate. Small choices accumulate like ripples.

Curiosity is also a form of care. Visit reputable marine centers that fund field science and prioritize welfare. Follow long‑term studies, not viral clips, and share evidence‑based stories with friends. I keep a habit of jotting questions after time on the water; it turns casual encounters into learning. Attention, multiplied by millions, changes policy.

Closing Current

Dolphins may not hold the secret to human intelligence – but they hold a secret to intelligence, period: that minds bloom in many shapes when environments demand creativity. Their path through sound and society shows how evolution can sculpt sophisticated cognition without our tools or texts. If we listen carefully, we might learn as much about our own minds as we do about theirs. The ocean is speaking through them. Did you expect that?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.