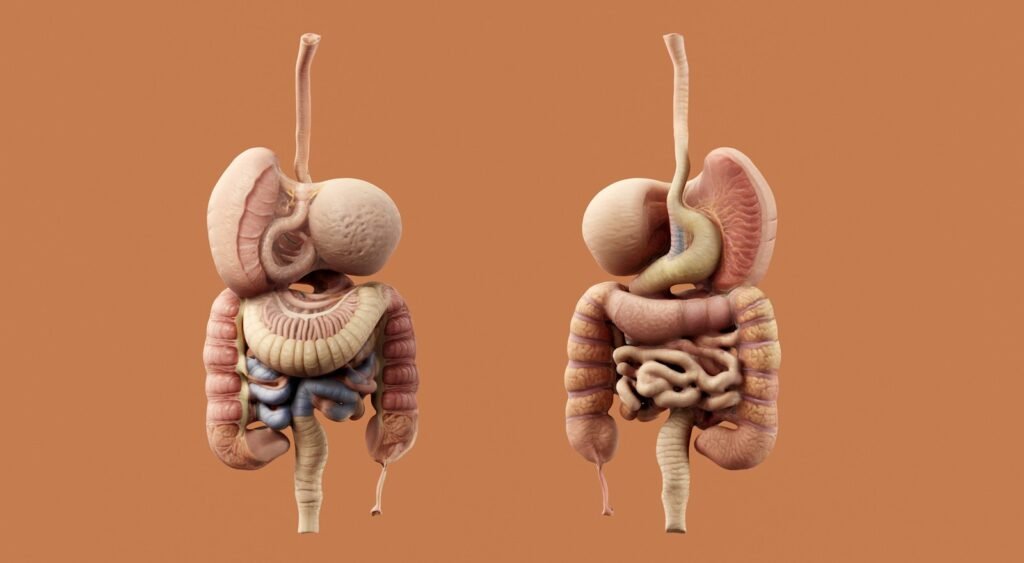

Scientists once treated the brain like a fortress sealed off from the messy business of digestion, but that wall is crumbling. In labs and clinics, a new picture is emerging where trillions of microbes in the gut can whisper to our mood, our stress responses, and even the way we think. The story isn’t neat or finished, and it’s definitely not a miracle cure; it’s a puzzle with pieces snapping into place in surprising ways. As someone who has stood in gnotobiotic mouse rooms that feel like clean, humming spaceships, I’ve watched nerves calm and behaviors shift when certain bacteria arrive. That sounds almost magical, yet it’s chemistry, wiring, and immune signaling doing the work – subtle, often small, but real enough to change the questions we ask about the mind.

The Hidden Clues

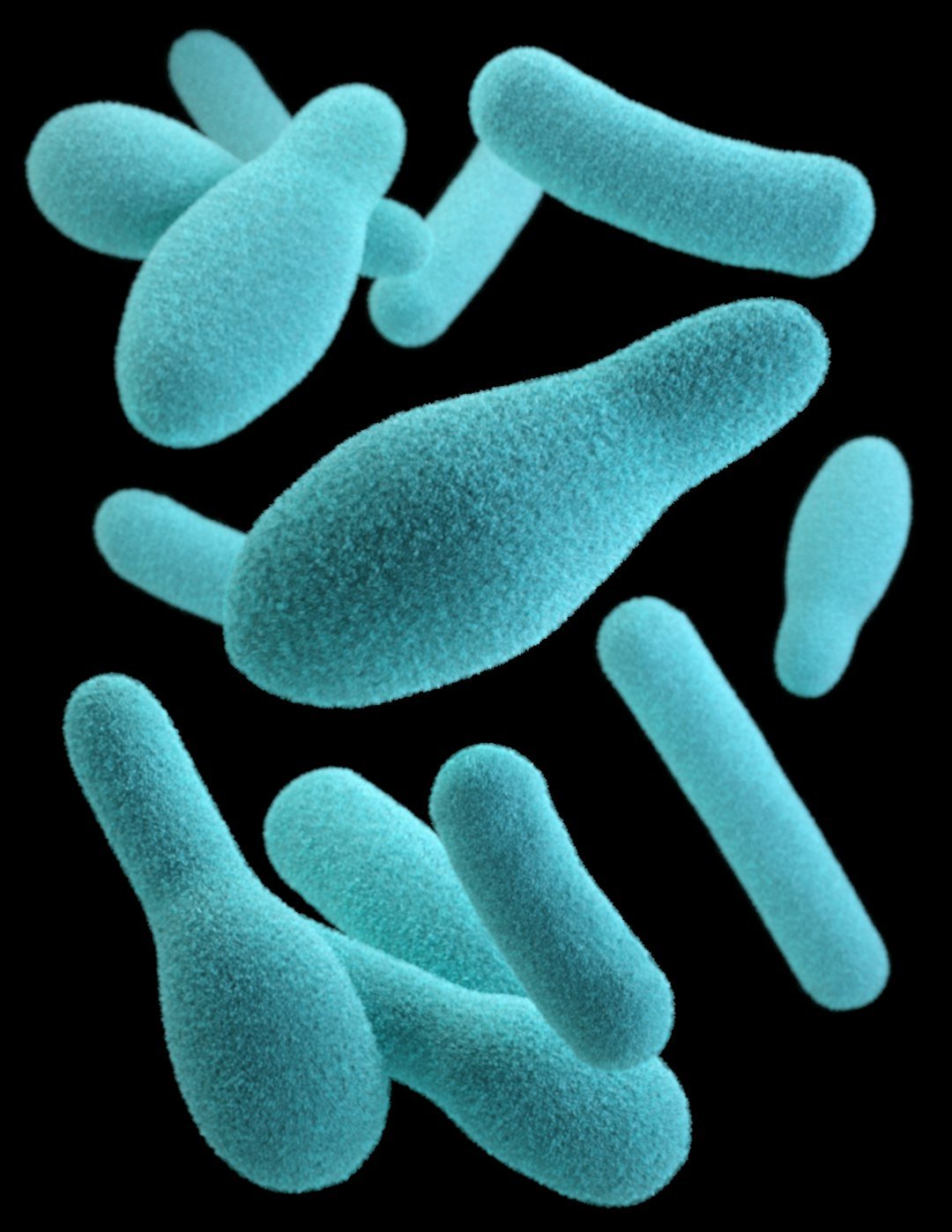

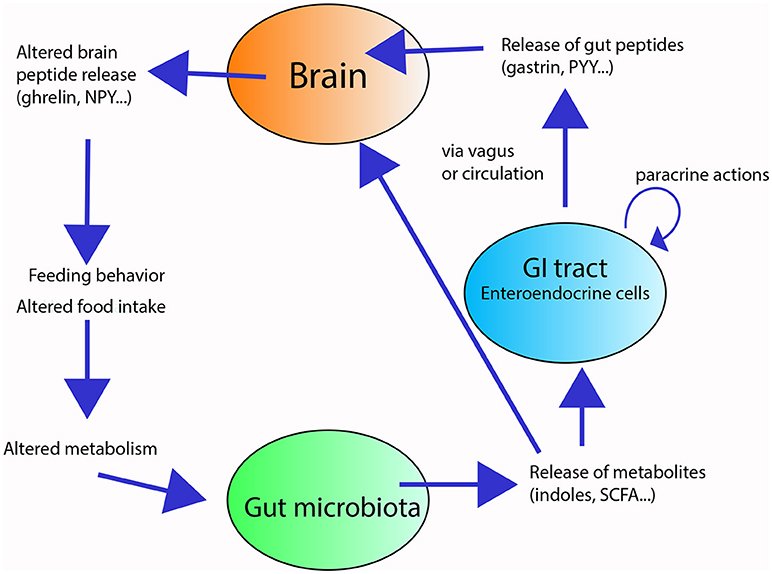

Look closely and the early hints were almost hiding in plain sight: people with irritable bowel symptoms often report anxiety or low mood, and stress can upset the stomach with suspicious speed. Researchers started to find that germ-free mice – animals raised without any microbes – show unusual behavior and altered stress hormones, and that colonizing them later can partly normalize those patterns. The idea of a microbiota–gut–brain axis took shape, pointing to a multi-lane highway of signals traveling through nerves, hormones, metabolites, and immune messengers. It’s not that microbes control us; it’s that they tune dials we thought were locked to genetics and life events. That tuning seems modest in many cases, but small changes in a sensitive brain circuit can matter a lot.

In people, studies have linked certain bacterial groups to depression severity and anxiety traits, while others correlate with psychological resilience. These are associations, not smoking-gun causations, yet the same players keep showing up: short-chain–fatty-acid producers that support gut barrier health, and organisms tied to inflammation when things go awry. Patterns look stronger when the gut is inflamed or stressed, suggesting a brain that’s already on edge may hear microbial static more loudly. That is both unsettling and empowering, because it means the signal might be adjustable. The clues point to a complex relationship – more duet than dictatorship.

From Petri Dishes to People

Rodent experiments made the first splash, but they could only take us so far. Human trials began testing probiotics, prebiotics, and diet changes, and a few reported small improvements in anxiety and low mood, especially in people under stress or with mild symptoms. The effects often look comparable to other gentle lifestyle tweaks: real, but not dramatic, and uneven between participants. That’s frustrating if you want a silver bullet, but it’s exactly what you’d expect when biology is personalized down to food, sleep, genetics, and past infections.

More rigorous nutrition trials – think high-fiber patterns and Mediterranean-style eating – have shown reduced depressive symptoms for some participants, alongside shifts in microbial metabolites. Researchers are also testing “postbiotics,” purified microbial molecules like butyrate mimics that may act more predictably than live organisms. Fecal microbiota transplants remain experimental for mental health and are currently approved only for recurrent gut infections, not mood or anxiety disorders. As the field matures, the focus is moving away from brand-name bugs and toward function: what a microbial community does may matter more than which species are present. That is a much harder target but a smarter one.

How the Conversation Travels

So how does a microbe in your colon talk to the brain in your skull? Part of the chatter rides the vagus nerve, which acts like a bidirectional phone line between organs and brainstem hubs that regulate stress and arousal. Another stream flows through chemistry: microbes produce short-chain fatty acids, tweak bile acids, and nudge tryptophan down pathways that can influence serotonin availability and inflammatory tone. The immune system is a powerful translator, relaying inflammatory whispers from the gut lining into signals that alter brain circuits and even microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells.

Importantly, most of the body’s serotonin sits in the gut and doesn’t cross into the brain, but gut-derived signals still shape the overall serotonin storyline by regulating precursors and receptors. When the gut barrier weakens, microbial fragments can heighten inflammation and stress reactivity, which many people feel as a blend of brain fog, irritability, and fatigue. On calmer days, the same crosstalk can be protective, reinforcing stress resilience. Think of it like the background music in a film: you might not notice it most of the time, yet it changes the way every scene lands. That’s the tone microbes can set.

Signals in a Stressed Body

Stress itself remodels the microbiome, tilting communities toward patterns that generate more inflammatory noise and fewer soothing metabolites. Poor sleep, irregular meals, and ultra-processed diets can amplify that loop, while exercise, fiber, and fermented foods tend to nudge it back. Antibiotics, when necessary, save lives; when unnecessary, they can scramble gut communities and occasionally coincide with mood dips in observational research. None of this means stress or antibiotics “cause” depression on their own, but the system is clearly sensitive to shock.

I still remember watching a lab demo where mice given a mild stressor showed different behaviors depending on the microbial metabolites they were fed. The change wasn’t dramatic, but it was consistent – like a dimmer switch rather than an on–off toggle. That’s the level where daily habits matter, especially across months and years. It’s also why quick fixes rarely hold; the system prefers slow rewiring. In mental health, that steady, boring consistency often wins.

Diet as a Lever

If gut microbes influence mood, then food becomes a tool, not a slogan. Diets rich in varied plant fibers feed microbes that make short-chain fatty acids linked to gut barrier integrity and anti-inflammatory effects. Fermented foods – yogurt, kefir, kimchi, miso – introduce live microbes and, perhaps more importantly, microbial metabolites that can shape the gut environment. Small clinical studies suggest that these patterns can reduce perceived stress and depressive symptoms for some people, complementing, not replacing, therapy or medication.

The catch is personalization: two people can eat the same bowl of beans and produce different metabolic concerts. That’s pushing researchers toward “function-first” metrics, such as profiling stool metabolites and microbial enzymes rather than tallying species. We may eventually match dietary tweaks to individual microbial signatures the way we match eyeglasses to vision tests. Until then, broad patterns – more fiber variety, fewer ultra-processed foods – are the reliable bets. They’re not flashy, but they move the needle.

Why It Matters

Traditional mental health care rightly centers on psychotherapy, social support, and medications with proven benefits. The microbiome adds another layer, not a replacement, offering biological footholds for people whose symptoms feel stuck or partly somatic. It reframes certain cases of brain fog, low energy, and stress reactivity as whole-body phenomena rather than purely psychological struggles. That perspective can reduce stigma and open doors to combined care plans where psychiatrists, dietitians, and gastroenterologists collaborate.

There’s also a pragmatic edge: modest, low-risk interventions like fiber diversity, fermented foods, regular exercise, and sleep hygiene can complement therapy and pharmacology. While effects vary, stacking small improvements often beats chasing a single breakthrough. Compared with past one-size-fits-all supplements, a microbiome-informed approach emphasizes measurable functions and outcomes. It challenges us to study mental health the way we study ecosystems – interconnected, sensitive, and responsive to environment. That’s a shift with real-world traction.

Global Perspectives

Microbiomes differ across regions, diets, and lifestyles, which means findings from one country may not map cleanly onto another. Rural and traditional diets often support microbial functions that urban, ultra-processed eating patterns erode, and that could change how stress and mood symptoms are experienced and treated. Access is uneven, too; high-cost specialty foods and tests won’t help if only a privileged slice can use them. Communities facing food insecurity need solutions that are affordable, culturally familiar, and nutrient-dense.

Public health programs that improve fiber access – whole grains, legumes, seasonal produce – could have downstream mental health benefits alongside cardiovascular and metabolic gains. School meals and workplace canteens are quiet leverage points, where small menu changes scale across thousands of people. Global science consortia are now comparing microbial functions rather than species lists to bridge cultural and dietary differences. That approach respects diversity while searching for shared mechanisms. It’s science that travels without flattening local realities.

The Future Landscape

What’s next looks both high-tech and surprisingly practical. Expect targeted “psychobiotics” that deliver specific functions, engineered strains that produce stabilizing metabolites, and postbiotics that skip the live-bug uncertainty. Digital twins – computer models built from your diet, microbiome, genetics, and symptoms – could simulate how a change might affect mood before you try it. Blood, breath, and stool metabolite panels may help clinicians track response just as they track cholesterol or inflammation today.

Barriers remain: standardizing tests, ensuring safety, and proving durable benefits across diverse populations. Placebo effects are strong in mental health research, so trials must be big, blinded, and long enough to matter. Regulators will need to balance innovation with caution, especially around live microbes and do-it-yourself stool transfers. Equity should be a design feature, not an afterthought, with interventions that work in clinics and community kitchens alike. If we do this right, the gut–brain story becomes practical medicine, not a passing fad.

What You Can Do

Start with foundations that help both brain and gut: regular sleep, daily movement, and stress-reduction practices you’ll actually keep, whether that’s breathing exercises or a walk with a friend. Aim for a rotating cast of plant fibers – beans, whole grains, nuts, seeds, and colorful vegetables – to feed microbial functions linked to resilience. Add fermented foods if they suit you, and introduce them gradually to avoid discomfort. If you’re curious about probiotics or prebiotics, talk with a clinician, especially if you take medications or have immune issues.

Avoid unnecessary antibiotics, but don’t fear them when they’re genuinely needed; you can rebuild afterward with time and diet. If you live with depression or anxiety, see the microbiome as an ally you can recruit, not a cure you must chase. Keep mental health care at the center and layer gut-friendly habits as support acts, not headliners. And if you’re able, support research efforts and community programs that make healthy food accessible to everyone. Small steps, stacked consistently, can change the score.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.