Picture this: you’re sitting in a coffee shop in Nashville, Tennessee, scrolling through your phone when suddenly, an urgent tornado warning blares across every screen in sight. Ten years ago, you might have raised an eyebrow and thought “That’s strange for this area.” Today? It’s becoming alarmingly normal. The iconic image of Dorothy’s house spinning through Kansas skies is giving way to a harsh new reality – America’s tornado activity is packing up and moving east, bringing devastation to communities that never saw it coming.

The data doesn’t lie, and frankly, it’s unsettling. More recently, that focus has shifted eastward by 400 to 500 miles. In the past decade or so tornadoes have become prevalent in eastern Missouri and Arkansas, western Tennessee and Kentucky, and northern Mississippi and Alabama – a new region of concentrated storms. We’re not talking about a minor adjustment here – this is a wholesale geographical revolution that’s rewriting the playbook on severe weather in America.

The Numbers Tell a Shocking Story

When meteorologists first started tracking this shift, they thought it might be a temporary blip. Boy, were they wrong. The shift has been ongoing since 1951, according to the study, which used information from two different datasets, each spanning 35 years, to determine where and when tornadoes have been forming. We’re talking about seven decades of gradual but persistent change that’s now reaching a tipping point.

Maps of patterns of tornadogenesis, or the process by which a tornado forms, show that between 1951 and 1985, tornado formation peaked in northern Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. But fast-forward to recent decades, and the picture looks dramatically different. Another map shows that from 1986 to 2020, tornadogenesis peaked in Mississippi, Louisiana and Alabama. Such events also were increasing further east, including Virginia, West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Illinois Breaks Records That Nobody Wanted

Illinois residents got a brutal wake-up call in 2024. National Weather Service data shows Illinois hit a new state record for tornadoes in 2024 with 142 reported. That broke a record of 125 reported tornadoes, set in 2006. That’s not just a statistical anomaly – it’s a glaring red flag waving in the face of climate reality.

The acceleration is mind-boggling. As of May 19, there were 92 reports of tornadoes statewide, according to the Illinois State Water Survey, setting a year-to-date record from the same time last year. Illinois State Climatologist Trent Ford told FarmWeek that by May 19 last year there had been just 58 reported tornadoes. That’s a roughly sixty percent increase in tornado activity in just one year.

The Climate Change Connection

Scientists aren’t mincing words about what’s driving this eastward migration. It’s an indication that the classic “Tornado Alley” region – the area from central Texas through Oklahoma and Kansas, so named because of the number of tornadoes there – is shifting eastward. And the culprit? Climate change is reshaping the atmospheric patterns that have governed tornado formation for generations.

Water temperature in the Gulf has also increased on average by one or two degrees, creating the moist, humid air needed for tornadoes. “One or two degrees may not seem much. But think of the difference between 32 degrees and 33 degrees,” Gensini said, referring to the temperature when water freezes. It’s a perfect example of how seemingly small changes can trigger massive consequences.

The western drought pattern is equally telling. A drought in the southwest is taking away needed moisture for the formation of twisters in the traditional Tornado Alley region. Persistent drought over portions of the plains is to blame. This shifted the path of warm, moist air farther east.

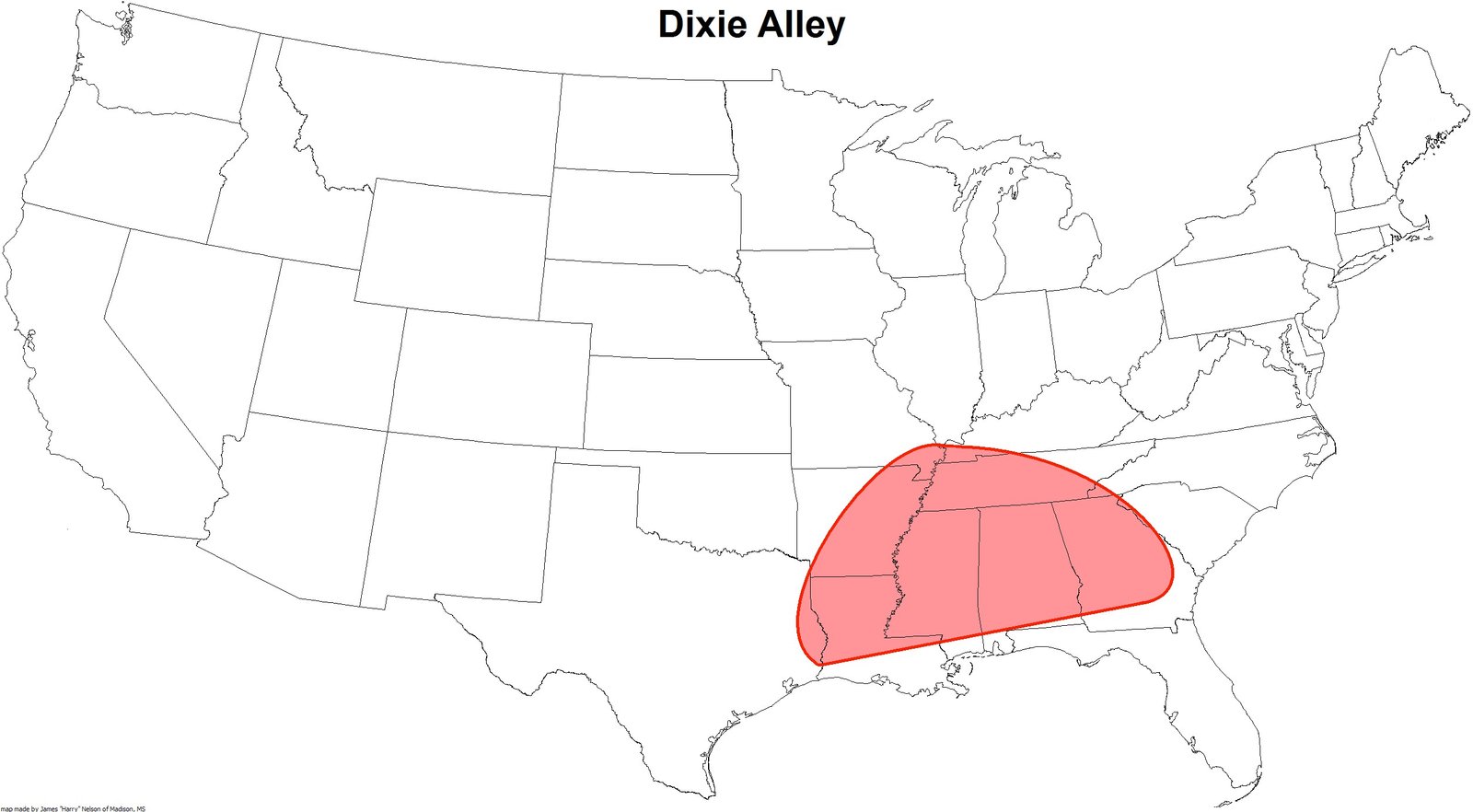

Enter “Dixie Alley” – A Deadlier Beast

Meteorologists have coined a chilling new term: Dixie Alley. Arkansas, scientists say, is nearly in the bull’s eye of a new tornado-prone area that’s referred to as “Dixie Alley.” The region, which has seen a vast increase in tornadoes over the past several years, also encompasses Mississippi, Alabama and western Tennessee. This isn’t just a geographical shift – it’s a transformation that makes tornado threats exponentially more dangerous.

Some argue this is distinct from the better known “Tornado Alley” and that it has a high frequency of strong, long-track tornadoes that move at higher speeds. The term was coined by National Severe Storms Forecast Center (NSSFC) Director Allen Pearson after witnessing a tornado outbreak which included more than 9 long-track, violent tornadoes that killed 121 on February 21–22, 1971. These aren’t your grandmother’s Kansas tornadoes – they’re bigger, meaner, and deadlier.

The Mobile Home Catastrophe

Here’s where the eastward shift becomes truly horrifying. The Southeast is more densely populated, and mobile homes, which fare poorly in windstorms, are much more common. We’re talking about a perfect storm of vulnerability that’s putting millions of Americans at risk.

The statistics are absolutely heartbreaking. Per the Associated Press, using data since 1996 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, approximately 40-50% of people killed at home during a tornado occupied manufactured homes, even though that classification of housing makes up only 6-10% of the housing stock in Dixie Alley. Think about that for a moment – more than half of tornado deaths occur in homes that represent less than one-eighth of the housing stock.

Tornado impact potential on mobile homes is 4.5 times (350%) greater in Alabama than in Kansas because Alabama, in comparison to Kansas, is represented by factors that create a catastrophic vulnerability gap between the traditional Tornado Alley and this emerging southeastern threat zone.

Nighttime Tornadoes Bring Silent Death

If the mobile home crisis wasn’t terrifying enough, there’s another factor that makes southeastern tornadoes particularly deadly. Tornadoes in the Southeast also occur at night more often than they do farther west, in part because winds can bring ample moisture from the Gulf after dark. Studies show that tornadoes that strike at night are 2.5 times more likely to cause fatalities.

Imagine being jolted awake at 2 AM by a tornado siren, having mere minutes to gather your family and find shelter while a mile-wide funnel cloud bears down on your community. Many of the storms occur overnight, when most people are sleeping and unaware that a tornado is approaching. When a tornado strikes, most people in the Southeast don’t have a basement or underground shelter. It’s a nightmare scenario that’s becoming increasingly common.

The Infrastructure Reality Check

The eastward shift isn’t just bringing tornadoes to new places – it’s exposing critical infrastructure weaknesses that have been decades in the making. The shift is serious: Tornado shelters are common in Texas and Oklahoma but less so elsewhere. Entire communities in the new tornado zones lack the basic protective infrastructure that Plains states have built over generations.

Very few fortified or underground storm shelters exist in the Memphis area. Due primarily to construction costs among other factors, basements are rare. In Tornado Alley, a large percentage of the population has either a basement or an accessible storm shelter, which are much safer than even a window-less interior room on the lowest floor, though that is often the safest place for most homes in our area. We’re essentially asking people to defend themselves against F4 tornadoes with interior closets.

Storm Chasers Can’t Keep Up

Even the storm chasers – those adrenaline-fueled scientists and weather enthusiasts who’ve made careers tracking tornadoes – are struggling to adapt to this new reality. Chimera Comstock, a storm chaser who has been chasing storms for almost 20 years, told AccuWeather in an interview that the shift in Tornado Alley has made storm chasing more challenging and more dangerous. Unlike the flat, open landscape and gridded road network in the Plains, forests and limited road options make storm chasing extremely difficult for Comstock and other chasers. She explained that instead of chasing the storm, she must now get into position ahead of the storm and hope the storm passes her location, potentially putting her or other chasers in immediate danger.

If professional storm chasers with decades of experience are finding these new tornado patterns dangerous and unpredictable, what does that mean for ordinary families?

The Warning System Breakdown

The eastward shift is breaking our traditional warning systems in ways that most people don’t realize. The Dixie Alley tornadoes accompanying the HP supercells are often partially or fully wrapped in rain, impairing the visibility of the tornadoes to storm spotters and chasers, law enforcement, and the public. Rain-wrapped tornadoes are essentially invisible killers – you can’t see them coming until it’s too late.

Tornadoes in the South tend to stay on the ground longer and move faster. Many storms in Dixie Alley are pushed by a stronger jet stream, which results in faster-moving storms. It’s not uncommon for a tornado in the Southeast to travel faster than 50 mph (80 kph). This puts more pressure on forecasters to get a tornado warning out in enough time for the public to react, CNN meteorologists say. The traditional 15-minute warning window that works in Kansas becomes utterly inadequate when tornadoes are racing across Tennessee at highway speeds.

The Social Vulnerability Crisis

Perhaps most troubling of all is how this eastward shift is disproportionately affecting America’s most vulnerable populations. The “social vulnerability” of those living in Dixie Alley is higher than in other tornado-prone areas of the country. The population skews a bit older, while mean income is lower, in Dixie Alley. In fact, the rate of tornado fatalities for those over age 50 is higher than the percent of the population of that age, while the reverse is true for those under 30, an indicator that older people are in general more vulnerable.

There is a “high degree of social vulnerability in the South,” explained the director of the Atmospheric Sciences Program at the University of Georgia to Yale Climate Connections, “[The South] encapsulates a population comprised of significant Black, Hispanic, elderly, and impoverished communities…such communities have the greatest sensitivity to extreme weather events and less capacity to bounce back from them.” We’re not just dealing with a weather phenomenon – we’re witnessing a social justice crisis unfolding in real-time.

What Scientists Are Seeing in the Data

The research community is scrambling to understand and quantify what’s happening. Data gathered in the past two years show that in addition to solo storms, large tornado outbreaks – multiple twisters spawned by a single weather system – are shifting even more definitively to the east. The swarms are clustering in a tighter geographical area than in the old Tornado Alley, too. And outbreaks may be getting fiercer and more frequent.

It looks as if we may be having fewer days in the U.S. with just one tornado and more days when there are multiple tornadoes,” says Naresh Devineni, an associate professor at City University of New York, who co-led a 2021 geographical analysis of large tornado outbreaks. We’re transitioning from isolated tornado events to coordinated atmospheric attacks that can devastate entire regions in a single day.

Conclusion: Facing an Uncomfortable Truth

The eastward shift of Tornado Alley isn’t some distant future concern – it’s happening right now, and it’s accelerating. The growing U.S. population is an even bigger concern than climate change, Strader says. “That’s scary to us, because that’s like saying, ‘If we woke up in a world without climate change, we’d still have a growing tornado problem.'” But climate change isn’t going anywhere, “so now what we have is this multiplicative effect,” Strader says.

We’re facing a perfect storm of climate change, inadequate infrastructure, vulnerable housing, and unprepared communities. The question isn’t whether more deadly tornado outbreaks will hit the Southeast – it’s when, and whether we’ll be ready for them. As tornado activity continues its relentless march eastward, millions of Americans are about to discover that the storms they thought belonged in Kansas are now knocking on their front doors.

What will it take for us to finally wake up to this new reality?