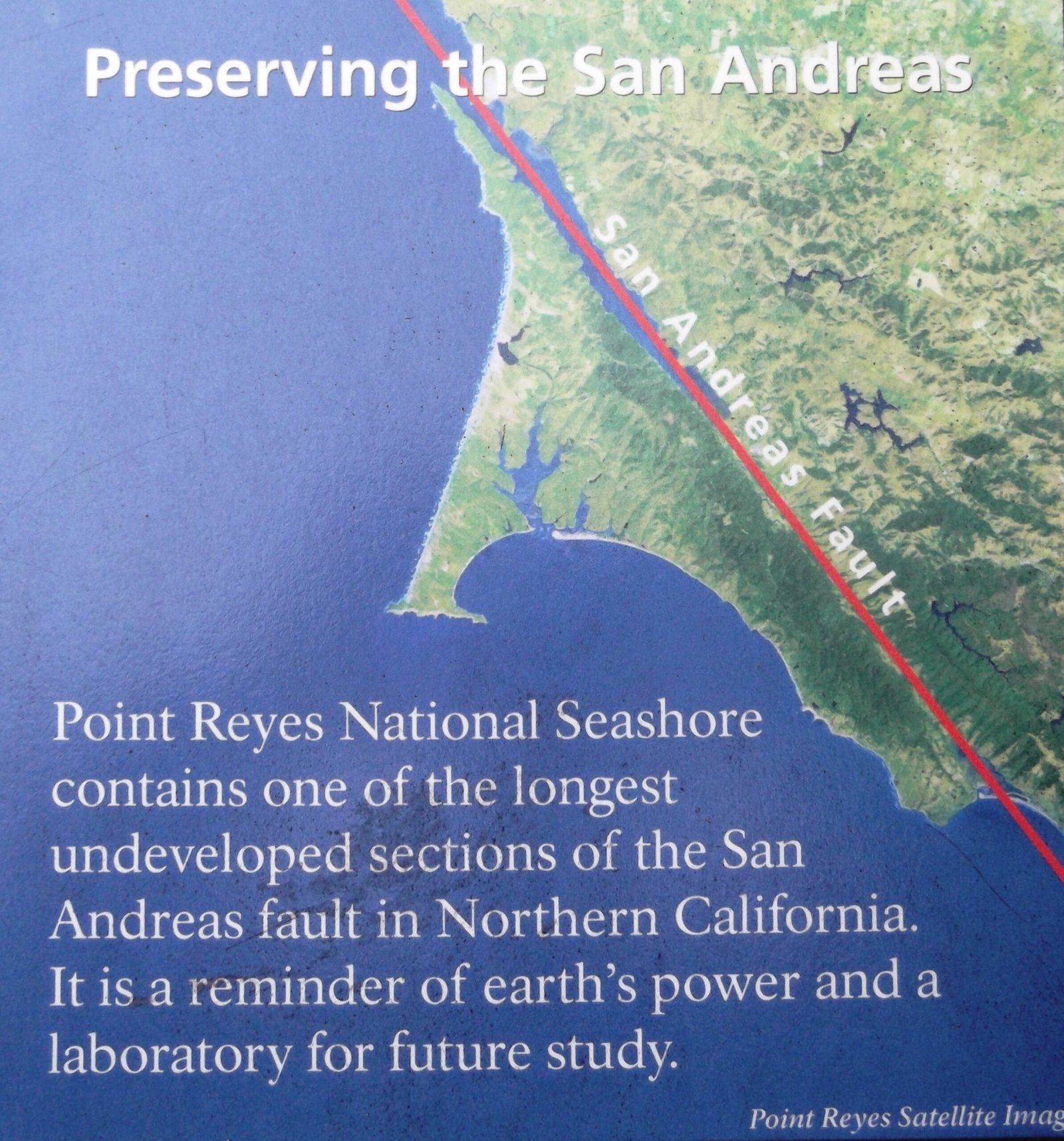

California’s most famous fault slices the state like a zipper, and every so often it pops a tooth. The question that keeps scientists, planners, and a lot of residents up at night is whether one big rupture could tug the next one along, domino-style, and set off a sequence that redraws maps and timelines. Decades of research now sketch a more nuanced picture, where stress can hopscotch across fault segments – but not always, and not everywhere. The mystery lies in how rocks remember strain, how tiny shifts pile up, and how the crust decides whether to keep going or call it quits. The stakes are very real for the millions who live, work, and build on and near this restless boundary.

The Hidden Clues

What if one rupture nudged the next, quietly, over hours or months, and we only noticed after the headlines faded? Seismologists have learned that earthquakes talk to one another through stress changes, and the messages aren’t always loud or obvious. Sometimes the signal is a subtle increase in tiny quakes near a fault bend or gap, other times it’s a lull that hides a slow, aseismic creep soaking up strain. I still remember standing on a sunbaked road cut near Parkfield, the so‑called earthquake capital, and watching a fence line offset by inches – a simple, startling reminder that not all motion makes the news.

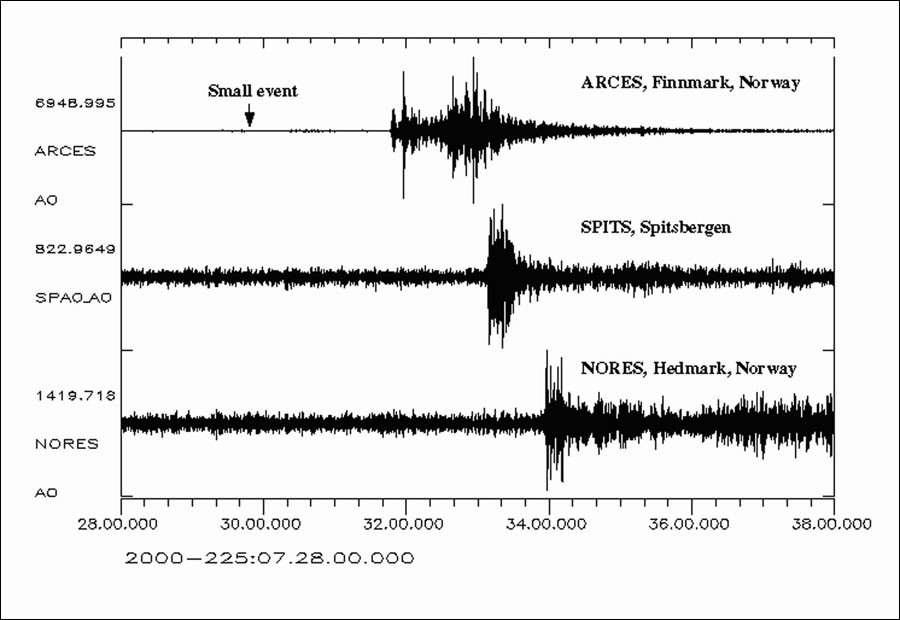

These clues are scattered like breadcrumbs in seismic catalogs, GPS time series, and satellite interferograms that reveal millimeter‑scale warps in the ground. The challenge is reading the pattern in time to guess whether the next step is a shrug or a shove.

Stress Transfer 101

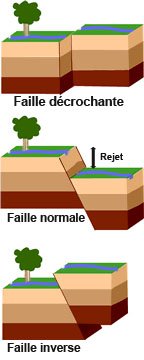

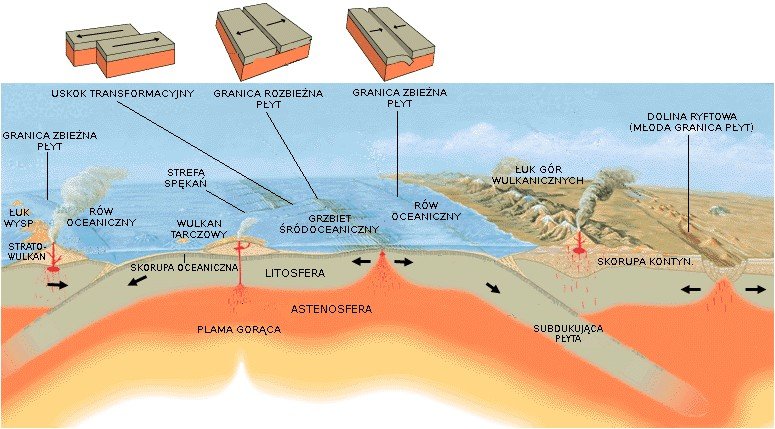

When a fault snaps, it doesn’t just end; it redistributes stress in a lopsided halo that can load the next segment while relaxing others. Scientists describe this with Coulomb stress change, a tidy way to track which patches get pushed closer to failure and which are nudged away. Dynamic triggering adds another twist, where the passing waves themselves can briefly tweak pressures in fluids deep underground and tickle distant faults into slipping. On the San Andreas system, these effects tend to be strongest near the ends of a rupture and at geometric oddities like jogs or step‑overs.

That means a large quake can plausibly raise the odds of another nearby in the following days to years, though most loaded patches still don’t break immediately. So, yes, transfers and cascades happen – but they’re far from guaranteed, and the crust remains a stubbornly inconsistent storyteller.

The Fault Is Not One Line

Calling the San Andreas “a single fault” is like calling a braided river one channel; the system includes parallel strands and connected faults that share stress. The northern, central, and southern sections behave differently, with a creeping middle stretch that oozes rather than locks and may act as a partial speed bump to runaway ruptures. Complex bends – especially the famously kinked Big Bend in Southern California – warp the stress field and can help stall a rupture or steer it onto a neighboring fault.

History and models suggest multi‑segment earthquakes are possible, but a full‑length rip across nearly eight hundred miles is considered very unlikely. Instead, think of a chain reaction as a series of hops, where a break on one segment raises probabilities on the next, sometimes completing the jump and sometimes fizzling. The practical upshot is a network that can share risk across multiple corridors instead of one tidy crack.

- Length: more than 800 miles, from the Salton Sea to Cape Mendocino.

- Behavior: locked, creeping, and transitional sections that load and release at different rates.

- Neighbors: major companion faults include the San Jacinto, Hayward, Calaveras, and Elsinore systems.

Lessons from Past Cascades

California’s record is sprinkled with episodes that look like choreography, even if imperfectly rehearsed. The 1857 Fort Tejon quake tore a vast stretch of the southern San Andreas, while 1906 unraveled much of the northern section; researchers still debate how long the stress echoes from those giants lingered. In 1992, the Landers earthquake stepped through multiple faults in the Mojave and was followed hours later by the Big Bear quake on a different fault, a stark, real‑world example of sequential rupturing. The 2019 Ridgecrest pair showed how an energetic foreshock and a mainshock can reorganize stress across orthogonal faults, reshaping hazard maps in a weekend.

Beyond California, the 2016 Kaikōura event in New Zealand stitched together more than a dozen faults in a complex cascade, underscoring what is physically possible in a mature fault network. These stories don’t prove that the San Andreas will domino end‑to‑end; they do prove that fault systems can improvise quickly and in surprising ways.

Global Perspectives

Plate boundaries around the world hint at the same rules but play different styles of music. Alaska’s 2002 Denali earthquake jumped from a thrust fault to a strike‑slip fault, while Turkey’s North Anatolian system has marched westward over the last century in a string of large events that look uncomfortably like a relay. Subduction zones, where plates dive beneath one another, can also cascade, but the physics and geometry differ from California’s mostly strike‑slip landscape. These comparisons matter because they stretch our imaginations about multi‑fault ruptures and help validate models that would otherwise be stuck in a California bubble.

They also remind us that infrastructure built for a single‑fault scenario might be underprepared for zigzag ruptures that cross fault boundaries. In short, the San Andreas isn’t unique, and that’s both reassuring and sobering.

Why It Matters

The chain‑reaction question is not an academic parlor game; it’s a planning problem measured in hospitals, aqueducts, ports, and power lines. Los Angeles, the Inland Empire, and the Bay Area sit next to interlocking faults, so a rupture that jumps segments could compound damage by striking multiple lifelines in rapid succession. Traditional hazard maps often assumed isolated, single‑segment events, but modern models now allow multi‑fault ruptures and time‑dependent probabilities after a major shock.

That shift changes how engineers think about bridge joints, pipeline shutoff valves, and the spacing of telecom backups. For emergency managers, it reframes aftershocks as part of a broader cascade window, where another large earthquake – on a nearby fault, not just the same one – is more plausible. Framed this way, preparedness is about resilience to a sequence, not just survival of a one‑off.

The Future Landscape

New tools are shrinking the blind spots that once made cascades feel purely mysterious. Dense seismic arrays and machine‑learning pickers now catch swarms of tiny quakes that can foreshadow stress migration, while GPS and InSAR satellites map slow, aseismic slip that can bridge the gap between felt events. West Coast earthquake early warning provides precious seconds to cut power, halt trains, and open firehouse doors, buying time in a world where seconds matter.

Researchers are also experimenting with time‑dependent forecasting that updates probabilities in the hours to years after a big quake, using physics‑based models that explicitly compute stress transfer across fault networks. Even with these advances, uncertainty remains baked into the crust; rocks are messy, fluids roam, and small features can throttle a rupture like a hidden choke point. The goal is not fortune‑telling but faster, clearer situational awareness when the ground starts re‑writing the plan.

Stress, Probability, and the Bottom Line

So can the San Andreas trigger a chain reaction down California’s spine? The most defensible answer is that partial cascades across segments are possible and have real, practical consequences, while a clean, full‑length rupture remains a remote scenario. Probabilities rise on nearby faults after a big event, but most of those heightened risks decay with time without breaking anything significant. The creeping middle section and geometric kinks likely reduce the chance of statewide runaway, even as companion faults present alternative paths for multi‑segment ruptures.

Think of the system as a crowded freeway at rush hour: traffic jams can spill from one lane to the next, yet the entire highway rarely freezes end‑to‑end. Planning that embraces this nuance – expecting hops, not a single unstoppable sprint – lands closest to what the science supports today.

Conclusion

Preparation works best when it’s ordinary and boring long before it’s heroic and urgent. Make or refresh a two‑week home kit, secure water heaters and bookshelves, and know how to turn off gas where you live. If you run a facility, schedule a drill that assumes a nearby large quake could be followed by another on a different fault within days, and test your backup communications with that in mind. Support local retrofits of unreinforced masonry, soft‑story apartments, and critical bridges, because strengthening known weak links pays off regardless of the exact rupture path.

Stay signed up for official alerts and the statewide earthquake early warning app, and practice what those extra seconds will buy you. Back the science by supporting regional seismic networks and fault‑mapping programs that keep hazard models honest and up to date.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.