Louisiana never seems to catch a break from nature’s watery assault. The state that sits like a sponge at the bottom of America faces a relentless cycle of flooding that keeps hammering communities year after year. From massive hurricanes to sudden downpours that turn streets into rivers, this low-lying region continues to battle an enemy that keeps coming back stronger each time. Rising sea levels and sinking land only make the problem worse, leaving many Louisiana towns with fewer natural defenses than ever before. Aging levees and drainage systems strain under the pressure, while wetlands that once acted as protective buffers are disappearing at alarming rates. For residents, rebuilding after each flood has become an exhausting routine, testing both wallets and resilience. Scientists warn that without stronger protections and long-term planning, these disasters will only intensify. What’s unfolding in Louisiana is more than bad luck—it’s a glimpse into the future of climate vulnerability across coastal America.

The Geography That Makes Louisiana a Sitting Duck

Louisiana is located along the southernmost part of the Mississippi River Basin, which has the largest drainage of any basin in North America. The state’s sub-tropical climate has the potential for producing heavy rainfalls at any time of the year. This isn’t just about bad luck – it’s about basic geography working against Louisiana in every possible way.

Picture trying to live at the bottom of a massive funnel where water from nearly half the continent eventually flows. By the time Katrina arrived, New Orleans lay at an average of one to two feet below sea level, with some neighborhoods even lower than that. Surrounded by water – Lake Pontchartrain to the north, and the Mississippi River to the south – and bordered by swampland on two sides, New Orleans has long relied on a system of levees to protect it from flooding. It’s like building a house in a bowl and hoping the rim holds forever.

When Drainage Systems Hit Their Breaking Point

Louisiana’s flooding problems aren’t just about too much rain – they’re about infrastructure that can’t handle the load when nature really lets loose. Rainfall totals of 6 to 10 inches were observed across metro New Orleans over a 2 to 3 hour period, and this overwhelmed the local drainage capacity resulting in widespread flash flooding throughout both the city of New Orleans and the surrounding suburban parishes. That’s what happened during the April 2024 flooding event that caught everyone off guard.

The brutal truth is that Louisiana’s drainage systems are fighting a losing battle against increasingly intense storms. The fast, heavy downpour overwhelmed roadside drainage systems, causing flash floods on several roadways. When systems built for normal rainfall get hit with what amounts to months of rain in just a few hours, it’s no contest – the water wins every time.

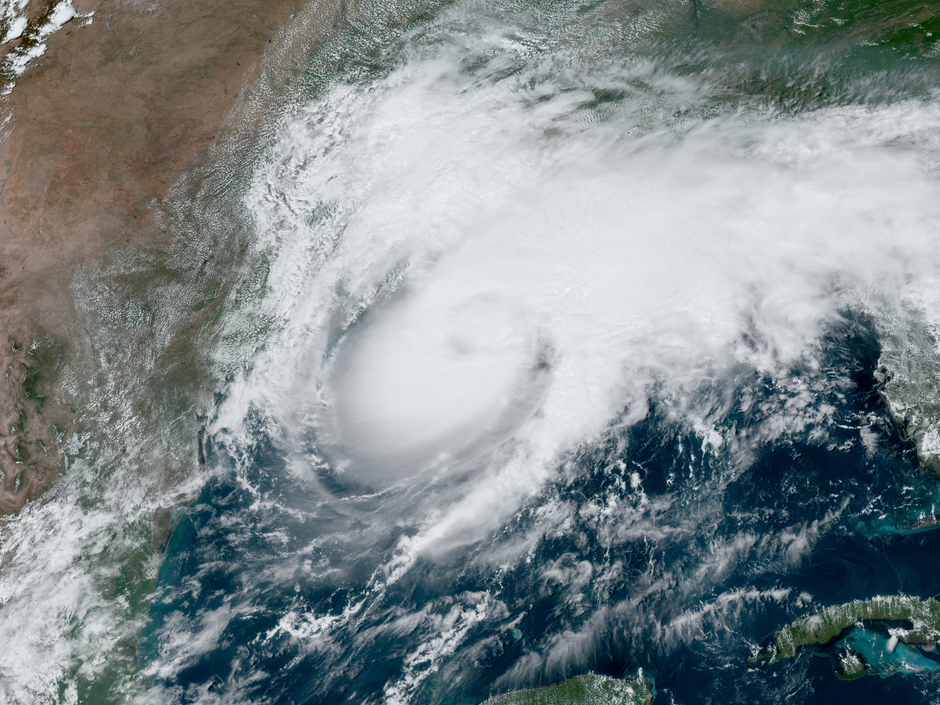

Hurricane Francine Shows How Fast Things Can Go Wrong

September 2024’s Hurricane Francine became a perfect example of how quickly flooding can destroy communities. Between 6 and 8 inches of rain deluged the area and triggered a rare flash flood emergency – the most severe flood alert – Wednesday night, according to the National Weather Service. The storm didn’t just bring wind – it brought chaos in liquid form.

Flooding has been reported at 350 structures in Louisiana’s St. Charles Parish, a parish spokesperson, Francesca Holt Blanchard, told CNN Thursday afternoon. In neighboring Jefferson Parish, more than 50 homes in the city of Kenner took on water during the storm, according to a city spokesperson. These weren’t just basement floods – entire communities found themselves underwater within hours. The storm exposed just how vulnerable Louisiana remains, even with all the improvements made since Katrina.

The Katrina Legacy That Still Haunts Louisiana

Hurricane Katrina changed everything about how people think about flooding in Louisiana, but not necessarily for the better. Almost half the fatalities in Louisiana were people over the age of 74 according to the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center 2010 The population of New Orleans fell from 484,674 in April 2000 to 230,172 in July 2006, a decrease of over 50 percent. That’s not just statistics – that’s an entire city essentially emptying out because people lost faith in their safety.

On August 29, 2005, flood walls and levees catastrophically failed throughout the metro area. Others collapsed after a brief period of overtopping (southeast breach of the Industrial Canal) caused scouring or erosion of the earthen levee walls. The engineering failures weren’t just technical problems – they were life-and-death disasters that showed how quickly modern infrastructure can become completely useless against nature’s power. Even today, the ghost of Katrina haunts every weather forecast and emergency planning meeting.

Hurricane Ida Proves History Keeps Repeating

When Hurricane Ida slammed Louisiana in 2021, it felt like watching a disaster movie sequel nobody wanted to see. Ida brought a devastating storm surge of nine to 14 feet to Plaquemines Parish, south of New Orleans, overtopping and then breaching a levee in Braithwaite that was not part of the new flood defense system, and flooding hundreds of homes. Despite billions spent on improvements since Katrina, Ida found the weak spots and exploited them ruthlessly.

The storm didn’t just bring flooding – it brought a harsh reality check. Some of the places hardest hit by Hurricane Ida’s Category 4 winds lie just south of New Orleans – a region of fishing villages, wildlife refuges, and oil and gas facilities. As Louisiana loses these wetlands at the rate of a football field every 100 minutes, it loses not only critical fisheries but also a buffer that protects New Orleans and other towns to the north This ongoing land loss means each storm gets a clearer path to populated areas, making future floods more likely and more devastating.

The Billion-Dollar Price Tag of Constant Flooding

Louisiana’s flooding problem isn’t just about inconvenience – it’s about money, massive amounts of it. From 1980-2024, there were 106 confirmed weather/climate disaster events with losses exceeding $1 billion each to affect Louisiana. These events included 15 drought events, 10 flooding events, 1 freeze event, 44 severe storm events, 27 tropical cyclone events, and 9 winter storm events. Each flood doesn’t just damage property – it chips away at Louisiana’s economic foundation.

The cost goes beyond immediate repairs. The Sewerage and Water Board of New Orleans says it needs about $1 billion to upgrade the city’s drainage system over the next decade – and it doesn’t know where that money will come from. That’s billion with a B, just for one city’s drainage improvements. Meanwhile, families are moving away, businesses are closing, and entire communities are questioning whether they can afford to keep rebuilding in the same flood-prone spots.

Pumps, Pipes, and the Infrastructure That Can’t Keep Up

Louisiana’s fight against flooding often comes down to mechanical systems that work great – until they don’t. Jefferson Parish President Cynthia Lee Sheng said three out of the four drainage pumps stopped working in Kenner. Unfortunately, today the pumps were overwhelmed and a lot of rain came in that last hour or so. When the systems designed to save you become part of the problem, you know you’re in trouble.

The reality is that Louisiana’s drainage infrastructure is playing constant catch-up with increasingly intense storms. Our system can’t really handle a lot of rain. A longer-term goal is getting a new power station up and running and having more green infrastructure in the city like ponds and permeable surfaces that can absorb more water. It’s like trying to empty a swimming pool with a garden hose while someone’s filling it with a fire truck – the math just doesn’t work.

The Vanishing Wetlands That Used to Protect Louisiana

Louisiana’s natural flood protection is literally disappearing beneath the waves, making every storm more dangerous than it should be. The rule of thumb is that every four miles of healthy marsh can absorb enough water to knock down a storm surge by one foot. The surge during Katrina peaked at 25 to 28 feet in certain places. Those missing wetlands aren’t just environmental losses – they’re like removing sandbags before a battle.

In less than one year, the state experienced a loss of over 150 square miles of estuarine emergent marsh and an increase of over 200 square miles of open water, mostly attributed to Katrina. Every football field of wetlands that disappears means storm surges can travel a little faster, hit a little harder, and reach a little further inland. Louisiana is essentially losing its natural armor one acre at a time, leaving communities increasingly naked against the next flood.

Small Towns Bear the Biggest Burden

While New Orleans gets most of the media attention, Louisiana’s smaller communities often suffer the worst flooding damage with far fewer resources to recover. Grand Isle in Jefferson Parish, a far south coastal town reachable by only one major highway, is a barrier island that suffered extensive damage from Hurricane Ida. Grand Isle was on the east side of Hurricane Ida’s eye, the most dangerous position to be in when a hurricane blows through. Six people rode out the storm in a motel that’s now nearly entirely destroyed. These communities don’t have backup plans or billion-dollar flood walls – they just take the hit and try to survive.

The pattern repeats across Louisiana’s rural areas where flooding doesn’t just damage property – it can wipe out entire ways of life. Fishing communities lose their boats and equipment, farmers lose crops and livestock, and small businesses lose everything. Without the resources of major cities, these towns often become ghost versions of themselves after major floods, never fully recovering before the next disaster strikes.

The Climate Change Reality Nobody Wants to Discuss

Louisiana’s flooding problem is getting worse, and pretending climate change isn’t part of the equation is like ignoring the elephant in the room while it’s stepping on your toes. Old infrastructure, subsidence and extreme rainfall caused by climate change are worsening flooding in New Orleans. The state isn’t just dealing with the same old storms – it’s facing a new level of intensity that makes past flood preparations look quaint.

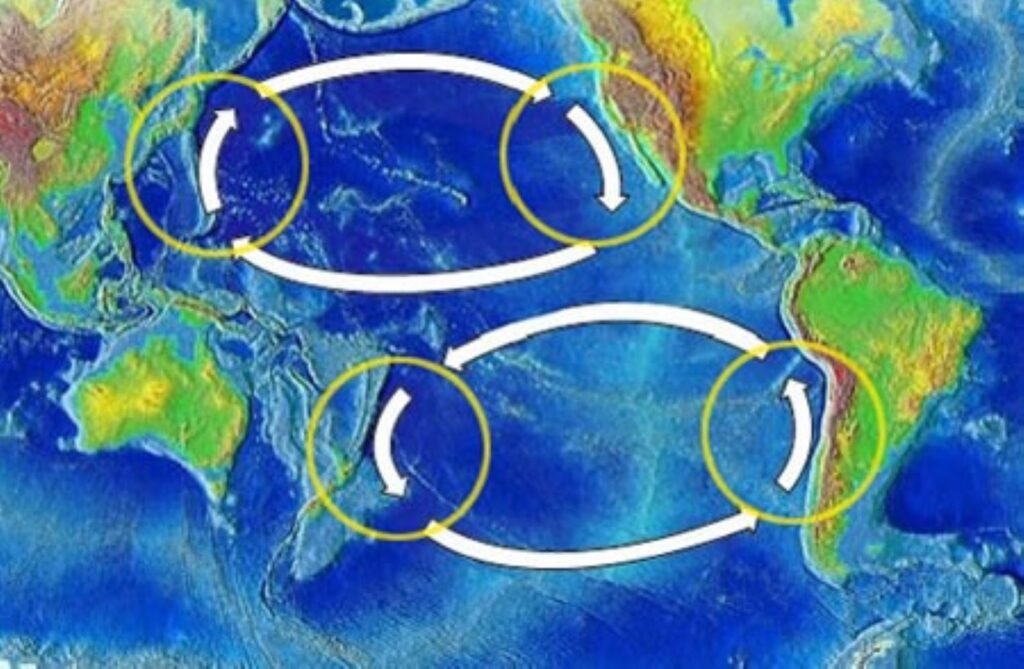

Hurricanes are heat engines that take heat energy out of the ocean and convert it to the kinetic energy of their winds. A hotter ocean will allow hurricanes to grow more powerful, assuming that the other factors that power hurricanes, including low wind shear and a moist atmosphere, are present. Climate change theory and computer modeling consistently show that we should expect to see the strongest storms growing stronger, with an increase in the proportion of Cat 4 and Cat 5 hurricanes that occur, as the planet warms. This means Louisiana’s flood problems aren’t temporary challenges to overcome – they’re the new normal to adapt to.

Looking Forward: Can Louisiana Ever Win Against Water?

The question isn’t whether Louisiana will flood again – it’s when and how bad it will be. No matter what officials do, New Orleans will continue to sink. The sea level will continue to rise. That’s not pessimism talking – that’s physics, geology, and climate science laying out a harsh reality that no amount of engineering can completely solve.

Indeed, state officials say the defenses held well against Hurricane Isaac in 2012 and Hurricane Ida in 2021. “The system performed as expected,” Barth says. Yet scientists and engineers are concerned that the extensive wetlands between the city’s perimeter and the coast’s edge, which continue to disintegrate badly, will allow future storm surges to march in unimpeded. Louisiana has made progress, but it’s like running up a down escalator – you might be moving forward, but the ground beneath you is moving in the opposite direction even faster.

Conclusion

Louisiana’s relationship with flooding reads like a story of stubborn determination meeting unstoppable force. The state keeps building, rebuilding, and improving its defenses, while nature keeps finding new ways to flood the same places over and over again. From Hurricane Katrina’s catastrophic levee failures to Hurricane Francine’s surprise drainage overloads, Louisiana towns face a recurring nightmare that seems to get worse with each retelling.

The real tragedy isn’t just the property damage or economic losses – it’s watching communities disappear piece by piece as residents give up hope and move away. Every major flood erases a little more of Louisiana’s cultural fabric, turning vibrant towns into cautionary tales about living where water wants to be.

What makes you wonder if there’s a point where stubbornness becomes foolishness?

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.