New Zealand’s most unlikely icon looks like a plush toy that wandered off the assembly line: rounded body, shaggy feathers, and a bill so long it seems to point to another postcode. Yet behind the charm is a scientific detective story about how a bird traded flight for feel, sight for smell, and wings for a life spent rummaging in the dark. For decades, researchers puzzled over how the kiwi became such an outlier among birds and what that odd, soil-probing bill really tells us about evolution. Now, a wave of paleontological finds, genomic insights, and field tech is stitching the picture together and it’s stranger – and smarter – than anyone expected. The kiwi didn’t just adapt; it rebuilt the rulebook for what a bird can be.

The Hidden Clues

Start with the egg, because the egg rewrites everything: a kiwi female lays a single giant egg that can weigh roughly about one fifth of her body, a physiological gamble that would terrify most species. That choice forces slow life histories – fewer chicks, more parental investment, and a body plan tuned for survival rather than speed. Pair that with a mostly nocturnal schedule, a burrower’s lifestyle, and wing bones so reduced they hide under the feathers, and you get a creature that treats the forest floor like a private pantry. On a wet night, you hear them before you see them, shuffling the leaf litter with quiet purpose. The shape may look comedic, but every curve and compromise fits an underground menu.

What puzzled early naturalists was the bill: long, flexible at the tip, and smelling rather than pecking its way through life. Unlike other birds, the kiwi’s nostrils sit practically at the front door of the world it explores – the bill tip – so scent arrives before touch. That single twist hinted at a deeper story of sensory trade-offs and evolutionary tinkering. The clues were there; science just needed the right tools to read them.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

The fossil record lifted its first veil in Central Otago’s ancient lakebeds, where early Miocene bones suggested kiwi ancestors were smaller and possibly more airborne than their present-day descendants. That discovery cracked the long-held idea that the kiwi lineage had always been grounded and undersized. DNA then doubled down, linking kiwis more closely to the hulking, extinct elephant birds of Madagascar than to their tall Australian cousins like emus. Suddenly, the narrative flipped: the ancestor likely flew to New Zealand, then shed the hardware of flight once predators were scarce and forests generous.

Modern genomics added the fine print by flagging genes tied to smell and touch, alongside hints of pared-back vision compared with typical day-flying birds. Field researchers layered in bioacoustics and GPS tags, showing how kiwis patrol territories like methodical surveyors, mapping food hot spots buried under ferns. I spent one rain-soaked night in Northland watching a kiwi test the ground with surgeon-level precision, and it felt like seeing a locksmith pick the forest floor. The tools have changed through time – from shovels and calipers to sequencers and passive recorders – but the story keeps sharpening.

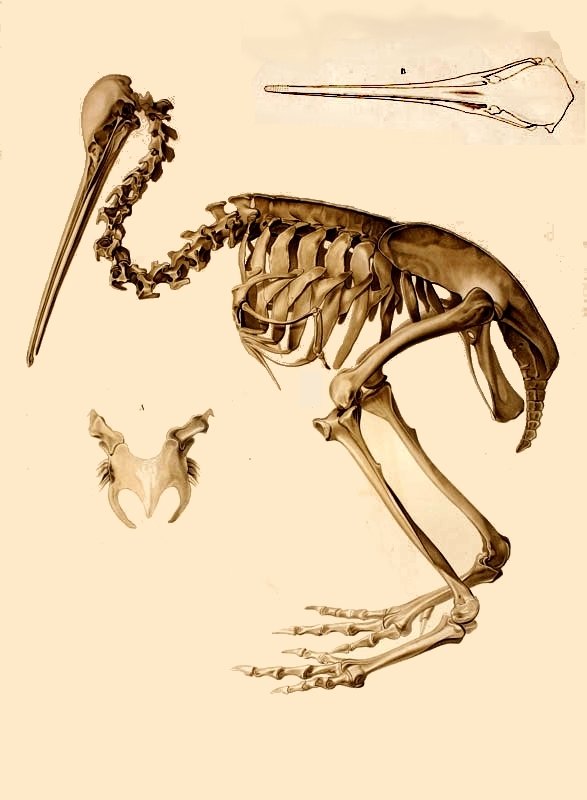

Anatomy of a Super-Snout

The kiwi bill isn’t a skewer; it’s a sensor array. Soft tissue at the tip brims with mechanoreceptors that detect faint vibrations, a stealthy way to find worms and grubs hidden in soil. Airflow funnels scent over nostrils at the very front, letting the bird essentially sniff the future location of dinner. Around the base, whisker-like feathers help with navigation, acting like bumper sensors in a midnight maze. Eyes play a supporting role; ears and bill run the show.

Look closely and you see an animal leaning into a different physics of foraging. Where a woodpecker turns trees into drumheads, the kiwi turns soil into sonar. Where a hawk searches with sight, the kiwi scouts with smell and micro-tremors. It’s not better or worse – just designed for the dark, damp economy of the forest floor. That’s why the bird’s silhouette looks round and low: a stable platform for a nose that never clocks out.

Evolution on an Island Edge

New Zealand sets the stage by subtracting what mainland ecosystems take for granted: native mammalian predators. In that quieter arena, flight becomes optional and stealth wins over speed, so wings shrink while legs thicken for digging and sprinting between burrows. Bones lose the air-filled architecture common in fast-flying birds and behave more like sturdy struts for a ground engineer. Feathers fray into hair-like strands that shed water and brush past obstacles without snagging, which is handy when your commute runs through fern tunnels at midnight. Evolution, in short, tuned the kiwi for a safe but sensory-challenging world.

Then people arrived and reshuffled the deck with dogs, stoats, and cats. The kiwi’s nighttime toolkit, built for quiet hunting, was suddenly asked to outwit unfamiliar teeth. Conservation has since become a second evolutionary pressure, choosing for birds that thrive near traps, sanctuaries, and fenced reserves. The story now dances between deep time on one side and real-time management on the other, and the species has to win both games.

Senses Rewired

When researchers dissect sensory trade-offs, they find a brain budget tilted toward olfactory and auditory processing. The olfactory bulbs are comparatively hefty for a bird, and the ears capture the forest’s low rustles and drips like a parabolic microphone. Vision hasn’t disappeared, but it’s not the star of the show, especially under the canopy after dusk. That sensory economy pays off in a place where dinner is hidden, soft, and nearly silent. It is the high craft of specialization, the kind that makes generalists look clumsy.

The payoff shows up in behavior: careful probing, short test jabs, and that unmistakable pause when scent locks on. A kiwi doesn’t waste moves; it audits the forest floor the way a chef tests dough. In ecology, efficiency is fitness, and the kiwi’s audit pays rent in worms, beetles, and larvae. That’s why their territories can be modest yet productive. If you can smell the pantry, you don’t need to run.

Why It Matters

The kiwi overturns the lazy assumption that birds are creatures of sight and speed. By thriving as a smell-first, touch-forward forager, it argues that evolution is less a ladder than a workshop full of custom hacks. For scientists, kiwis are a living case study in how senses expand when ecological niches invite them, an idea with echoes in bats, moles, and even cave fish. For engineers and roboticists, the bill is a blueprint for low-light, low-power search – think disaster-response bots that sniff and feel their way through rubble rather than relying on cameras alone. In conservation, the kiwi is a stress test for predator control and community-led stewardship.

To ground the stakes, consider a few hard realities and promising shifts:

– In unmanaged areas, kiwi chicks often face deadly odds from introduced predators during their first months.

– On intensively trapped landscapes and fenced sanctuaries, juvenile survival rates can improve dramatically, turning local declines into slow climbs.

– Translocations to predator-reduced urban fringes show that people can live near kiwis if dogs are leashed and cats are curfewed.

The Future Landscape

What comes next mixes gritty fieldwork with futuristic tools. Acoustic networks now listen for kiwi calls across valleys, allowing teams to map populations without stepping into every ravine. Environmental DNA in soil and streams can reveal where kiwis have been, a forensic footprint for a bird that prefers the night shift. Drones and thermal cameras help scouts find burrows without trampling habitat, while tiny GPS tags sketch movement maps that feed smarter predator control. Even artificial intelligence enters the picture, sorting calls, spotting patterns, and nudging rangers where effort pays off most.

All of that matters because climate shifts are reshaping forests, soils, and invertebrate communities. Drier spells can harden ground and starve the pantry; extreme storms can flood burrows and hammer chicks. The biggest wild card remains predator pressure, which is why New Zealand’s long-haul ambition to curb invasive mammals has become a national moonshot. Expect tough debates over biotech tools and long-term funding, but also steady wins as communities trap, fence, and restore. The kiwi’s future is a patchwork built season by season, valley by valley.

Conclusion

Keeping this feathered potato with a super-snout on the landscape is both science and habit. If you live or travel in kiwi country, leash dogs at night, slow down on forest roads, and treat burrow zones like do-not-disturb signs. Support local trapping groups, sanctuaries, and schools that teach kids how to be good neighbors to nocturnal wildlife. If you’re far away, back the research: monitoring projects, genetics labs, and community rangers all run on shoestring budgets that bright minds stretch into real gains. The kiwi adapted to a world that once fit it perfectly; now we have to help the world bend back just enough for it to thrive – are you in?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.