In a world where most prehistoric creatures can be tucked into neat textbook boxes, one animal refuses to sit still. The five-eyed oddity from the Cambrian – best known from sites like Canada’s Burgess Shale and China’s Chengjiang – keeps slipping between categories, teasing scientists with traits that look both familiar and alien. It sports a flexible, hose-like snout, flaps along its sides, and a crown of eyes that seem borrowed from a science-fiction sketchbook. Every time researchers think they’ve pinned it down, new data nudges the story sideways, revealing a mosaic rather than a single clear picture. That’s exactly why this creature matters: it forces us to rewrite the early chapters of animal evolution with a sharper pencil.

A Creature with Five Eyes

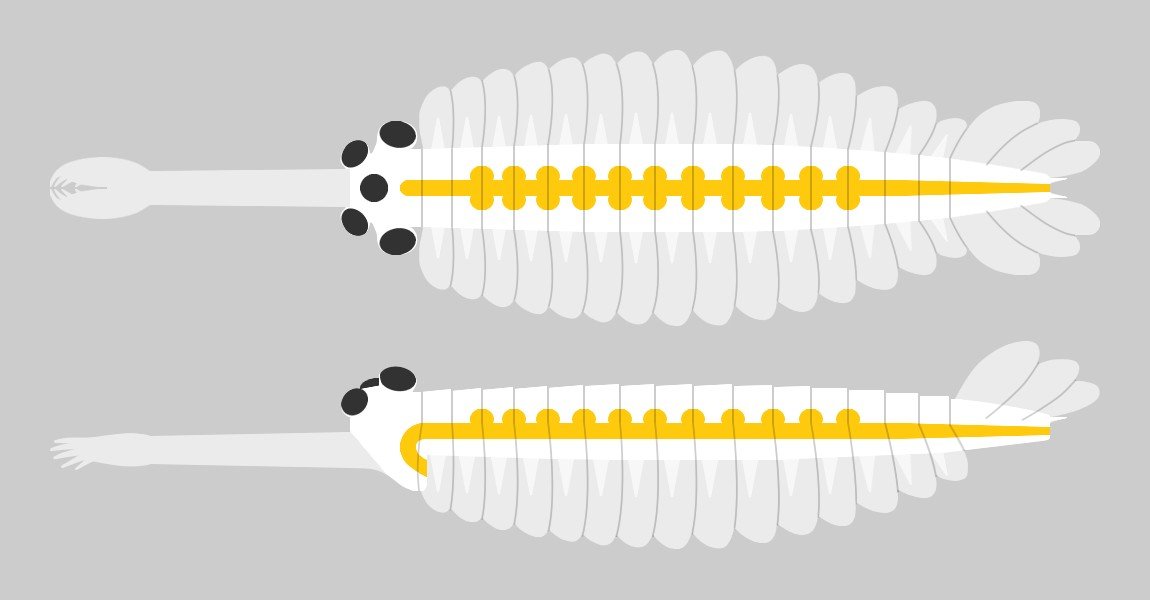

Five eyes on a small head (the entire animal was only about 7 cm long) sounds like a prank, but these stalked or bulging orbs were very real and very useful in Cambrian seas. Picture a low-slung swimmer scanning its surroundings in multiple directions at once, like a living periscope that never blinks. The flexible proboscis up front could have been a precision tool, able to probe, pluck, or funnel food toward the mouth, a kind of biological Swiss Army knife for a world with few rules.

Fossils place these animals at roughly 505-508 million years old, right in the surge of biodiversity often called the Cambrian explosion. Some specimens lean toward a kinship with the earliest arthropods – relatives of today’s insects, spiders, and crustaceans – while others follow their own branch. The result is a creature at the hinge of evolutionary history, where experimentation was the norm and blueprints were still wet.

The Hidden Clues

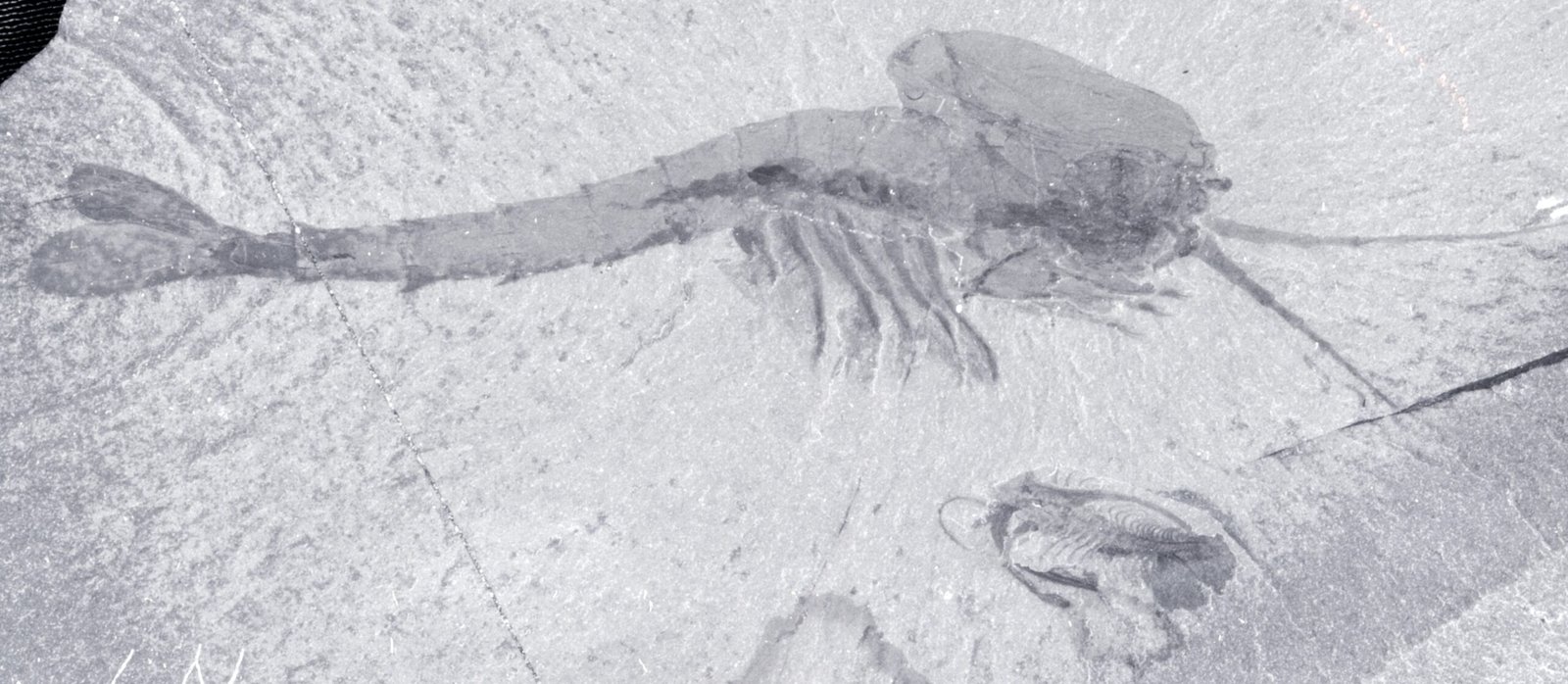

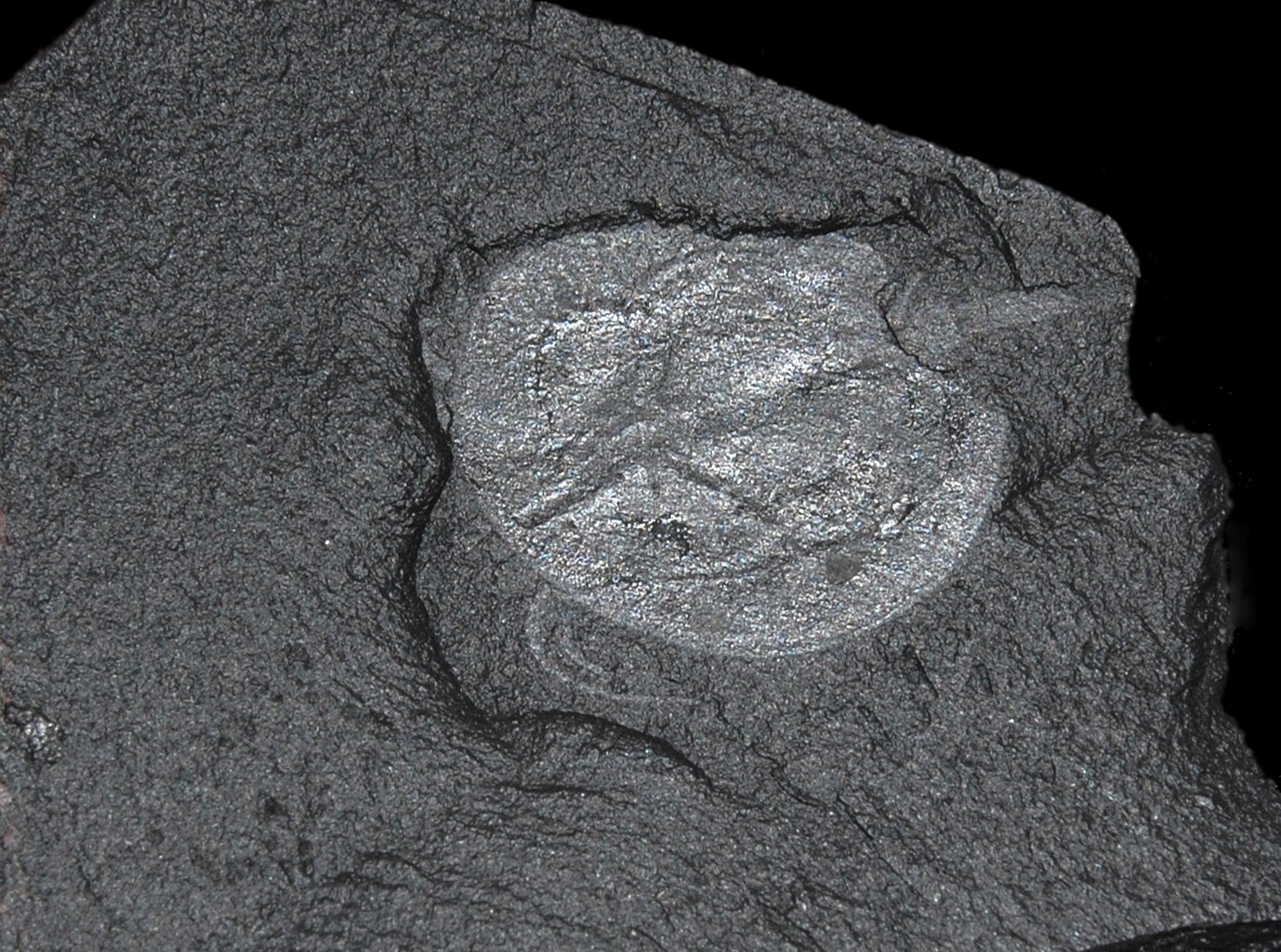

Soft-bodied fossils are notoriously stingy with details, yet these slabs preserve ghostly hints of anatomy: delicate gill filaments, overlapping side flaps, and a segmented trunk that whispers of arthropod affinities. Those five eyes aren’t just a party trick; they reveal an investment in vision long before reefs teemed with complex predators. Even the proboscis tells a story, with its ringed structure and terminal grasping parts suggesting a lifestyle built on precise handling.

Taphonomy – the science of how organisms become fossils – adds another layer. Fine-grained muds sealed these animals fast, locking in the sort of tissues that usually rot away. Chemical halos around organs and limbs map former biology in unexpected colors when scientists light them up in the lab.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Today’s researchers bring a toolbox that would have seemed like sorcery a generation ago. Laser-stimulated fluorescence reveals patterns invisible under white light, while elemental mapping shows where different tissues once sat. Synchrotron and micro-CT scans help reconstruct 3D shapes inside flattened rock, rescuing anatomy lost to compression.

I remember watching a technician rotate a digital fossil like a tiny planet, peeling back layers to reveal a tucked-under appendage. That sort of virtual preparation replaces guesswork with geometry. It’s slower than a headline but far more persuasive than hand-waving diagrams.

Rewriting the Arthropod Family Tree

For years, textbooks drew a straight line from simple worm-like ancestors to armored arthropods with jointed legs. The five-eyed fossil scribbles a more tangled path, blending features seen in radiodonts – those early, swimming predators with frontal grasping appendages – and in later true arthropods with rigid exoskeletons. It doesn’t crash the party; it shows us the party was already crowded and loud.

Transitional doesn’t mean halfway; it means a bundle of traits evolving at different tempos. Eyes could sprint ahead while body armor lagged behind, or sensory systems could mature before jaws standardized. What we’re seeing is not an oddball outlier, but a snapshot of evolutionary traffic in full rush hour.

Why It Matters

This animal is a stress test for our categories, a reminder that life invents, borrows, and remixes as it goes. By forcing a rethink of what counts as “arthropod enough,” it sharpens the definitions used across paleontology, developmental biology, and evolutionary genetics. The implications reach well beyond one fossil bed.

– It strengthens the case that complex sensory systems evolved early, shaping predator–prey arms races sooner than many assumed.

– It highlights how major body plans did not appear fully formed; they accreted piece by piece.

– It offers calibration points for molecular clocks, letting genetic timelines anchor to hard evidence.

– It reframes the Cambrian not as chaos, but as organized experimentation with lasting consequences.

The Future Landscape

Expect a flood of new data as imaging becomes gentler and sharper, revealing microstructures once dismissed as smudges. Machine-learning tools are beginning to flag patterns in fossil images – subtle repetitions in eye facets, filament spacing, or segment boundaries – that a tired human might miss. When paired with open databases, those tools could turn scattered specimens into a coherent, searchable atlas of early animal form.

Fieldwork will still matter, maybe more than ever. Some of the best sites are under pressure from weathering, development, or regulatory shifts, so careful stewardship will decide what future scientists can study. New quarries and overlooked museum drawers are likely to recast the five-eyed creature yet again.

The Hidden Clues in the Rocks Themselves

Geology frames biology in these stories, and the Cambrian seas left fingerprints in each layer. Subtle changes in sediment grain size can reveal whether a carcass drifted, got buried in a storm, or was entombed quietly on the seafloor. Each mode of burial preserves different organs, biasing what we think the animal looked like.

Chemistry helps correct for that bias. Sulfur and iron distributions, for example, can betray former soft tissues, while phosphorus can trace gut contents or muscle. The result is a kind of forensic triangulation, matching anatomy, environment, and decay to rebuild the living creature with fewer blind spots.

From Puzzle to Playbook

Once you accept that no single fossil holds the whole truth, the five-eyed animal becomes a playbook rather than a puzzle. One specimen emphasizes the head, another the trunk, a third the appendages; the ensemble, not the soloist, carries the melody. This is how science grows up – by comparing, arguing, and iterating.

And those debates aren’t academic footnotes. They shape how we model early ecosystems, estimate evolutionary rates, and teach the origins of familiar animals. A shrimp or a dragonfly on your windowsill is stranger – and older in spirit – than it looks.

What You Can Do

Start local: visit natural history museums and ask to see their Cambrian collections, many of which rotate through storage. Public curiosity pushes institutions to display, digitize, and fund research on specimens that might otherwise gather dust. If you’re near fossil parks with legal collecting, learn the rules and report unusual finds.

Support open science where you can. Donations to digitization projects and community labs stretch the reach of each specimen, letting students and researchers worldwide examine high-resolution models. If nothing else, share the story – five eyes are hard to forget, and wonder is a renewable resource.

Conclusion

Half a billion years on, the five-eyed enigma still stares back at us, insisting we look closer and think harder. It is both familiar and foreign, a reminder that evolution tinkers like a patient artisan rather than a hurried engineer. With every new scan and specimen, the outlines sharpen, and the animal becomes less of a monster and more of a neighbor in deep time.

I’ve stood over a gray slab and felt that vertigo – the sense that our tidy explanations are too small for the evidence. That feeling is the point. Isn’t it thrilling when nature refuses to be simple?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.