On New Zealand’s wild West Coast, the Karamea shoreline is a restless machine: tides sweep the Ōtūmahana Estuary, channels wander, dunes shift, and stories rise and disappear with the sand. That makes a provocative question feel almost inevitable – could traces of the first people lie hidden here, waiting to reset timelines we thought were settled? Current evidence places the earliest Māori settlement in the mid‑thirteenth century, but footprints – if ever found and securely dated – can compress prehistory into a single, undeniable moment. Around the world, prints have rewritten chapters before. In Aotearoa, they would do more than nudge a date; they would illuminate how and where voyagers first met this coast. And Karamea, with its mix of estuary mudflats and long, storm‑cut beaches, is the kind of place where fleeting steps sometimes fossilize into facts.

The Hidden Clues

Karamea’s landscape is a patchwork of clues already: large shell middens speak to intensive harvests of pipi in centuries past, while nearby sites on the Heaphy coast show toolmaking, argillite flaking, and long, seasonal occupations. None of that is as dramatic as footprints, but it frames the question – people have been here since the earliest phase of settlement, and their subsistence strategies left measurable traces. Archaeologists working middens in the Karamea area have documented a sudden shift to specialized shellfish gathering late in the fourteenth century, consistent with the broader narrative of rapid South Island expansion after first arrival. Those patterns match what demographic models infer for the region. It means Karamea is not an archaeological blank; it’s a canvas with room for one more stroke. If distinct human trackways emerged from these sands, we’d know where to pin them within a living cultural landscape.

The catch is preservation. Footprints need a delicate sequence: soft sediment to mold the step, quick burial to lock in the shape, and stable conditions to keep it intact. Estuaries can provide exactly that, but they can also erase everything in a single storm. On my last wander up the Ōpārara Basin in drizzly weather, I watched the river lift and drop entire slabs of sand like book pages; any trackway there survives by luck and timing. That’s why researchers talk about probability rather than certainty when they survey Karamea flats. The clues exist in pulses, revealed and hidden by waves, and you have to be looking at the right hour.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

If you’re trying to turn a faint heel mark into a firm date, you need a toolkit as layered as the sediment. Photogrammetry captures three‑dimensional geometry within minutes, preserving delicate surfaces before tides reclaim them. Dating comes next, and here scientists have learned hard lessons: use multiple independent methods – optically stimulated luminescence on quartz grains, radiocarbon dating on short‑lived terrestrial plant remains or pollen, and stratigraphic correlation – to converge on an age. That multi‑line approach was crucial at White Sands, New Mexico, where human prints were confirmed to be roughly between twenty‑one thousand and twenty‑three thousand years old. The team cross‑checked radiocarbon with luminescence, reducing the risk of bias from a single material. The same playbook would guide any Karamea footprint study from day one.

Even then, caution rules. Dating aquatic plants can skew old if they pull carbon from dissolved sources, a critique that briefly rattled confidence at White Sands before further tests resolved the issue. That episode matters here because West Coast estuaries are full of aquatic vegetation and reworked carbon. Investigators would favor pollen trapped within the footprint layers and OSL on the enclosing sands, not just whatever organic bits are easiest to collect. They’d also map micro‑stratigraphy millimeter by millimeter to ensure the print sits exactly where the dated grains do. The goal is simple: build an age case that stands up to scrutiny outside the heat of discovery.

Reading the Prints

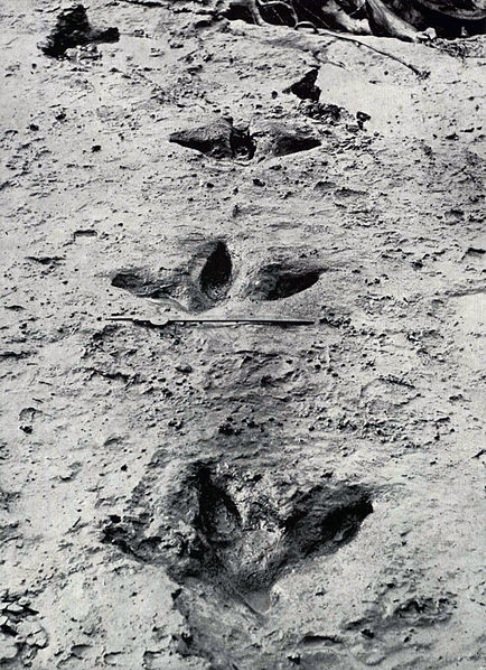

What counts as a human footprint? It sounds obvious until you meet the moa. New Zealand’s extinct giants left deep, three‑toed impressions that can mimic a human heel‑and‑ball silhouette at a glance, especially when erosion rounds the edges. Recent discoveries in the Kaipara region captured moa walking at the top of an ancient beach, their steps infilled by dry sand and later preserved in soft sandstone – a reminder that trace fossils in Aotearoa are often avian. Analysts look for hallmarks: the forward big toe, a defined arch, stride length within human ranges, and left‑right patterning consistent with bipedal gait. They also compare across multiple prints, because a single ambiguous mark proves very little. Context, repetition, and geometry carry the argument.

Aotearoa does have confirmed human footprints – in the ash on Motutapu Island, where people and their dogs walked across fresh tephra from the Rangitoto eruptions about six to seven centuries ago. Those prints sit inside a well‑dated cultural horizon with artifacts, which makes them powerful teaching cases for how to sort signal from noise. Any Karamea claim would need similar rigor: a trackway with multiple coherent prints, human‑style gait metrics, and secure stratigraphic context. Add in microfossils or pollen from the same layer, and the evidence strengthens. In science, prints are never just pictures; they’re hypotheses you can measure.

The Tides of Time

Karamea’s estuary is a restless engineer. Survey records show its sea outlets have migrated roughly several kilometers along the shore in the past century, periodically exposing new surfaces and burying others. That dynamism helps explain why potential track surfaces may appear and vanish on seasonal cycles. It also means any find becomes a race against erosion, just as it has at other coastal tracksites worldwide. Field teams have to work with the tide clock, documenting in hours what nature might erase overnight. In a way, the estuary itself is the co‑author of any discovery narrative here.

All of this has implications for conservation. A print on a firm, damp sand bed needs quick sheltering; even a protective sand cap can buy time until extraction. Local partnerships – iwi, community groups, museums, and conservation staff – matter because rapid permissions and trained responders make the difference between a saved trackway and a story told in past tense. Karamea has experience coordinating over sensitive habitats and artworks, from estuary protection to cultural installations. The workflows already exist; archaeology can plug into them with minimal friction. That readiness is part of why Karamea is a compelling place to look.

Why It Matters

The timeline for first settlement in Aotearoa is not a guess; it rests on hundreds of radiocarbon dates and sophisticated modeling that point to an arrival in the mid‑thirteenth century, first in Te Ika‑a‑Māui and about a decade later in Te Waipounamu. A secure footprint layer at Karamea dated earlier than that would be a profound challenge to a well‑tested framework. More plausibly, a Karamea tracksite could refine regional pacing – showing when early communities regularly used this coast, how they moved through estuaries, and whether children and dogs were part of those journeys, as at Motutapu. It would also knit together local shell‑midden stories with literal steps on the ground. In short, it would make the abstract curve of settlement feel human‑scale. That’s not just academic; it deepens place‑based identity for communities who live with these landscapes.

Consider the practical ripple effects: evidence‑based heritage management, stronger safeguards for dynamic shorelines, and richer public interpretation along walking tracks and visitor centers. It would also sharpen scientific questions we can test elsewhere on the West Coast. For emphasis, here are the stakes in plain terms – earlier verified prints could shift regional arrival estimates; well‑dated fourteenth‑century prints would confirm the speed of coastal spread; prints with child steps or canine marks would illuminate social life on the move. These gains align with broader goals of restoring, protecting, and sharing Māori heritage tied to specific places. They also encourage long‑term monitoring of estuaries where history surfaces with the tides. Evidence that people walked here early – and often – changes how we care for the shore.

Global Perspectives

Footprints carry unusual authority because they capture behavior at the scale of minutes. At White Sands, the tracks of Ice Age walkers – now tightly dated with multiple techniques – reset debates about when people reached North America. In Britain, early hominin tracks at Happisburgh briefly appeared between tides, then vanished, their record preserved only through fast photogrammetry. These cases show how a few steps can upend timelines if the geo‑story behind them holds up. They also show how quickly coastal evidence can be lost if not documented in time. Karamea’s sands belong on that global shortlist of places where prints could matter outsized.

There’s another lesson from those sites: controversy is not a bug, it’s a feature. Claims invite counter‑claims, methods get stress‑tested, and stronger conclusions emerge. The White Sands team, for instance, addressed critiques about old carbon by targeting different materials and using luminescence – an approach any Karamea project would likely mirror from the outset. International collaborations help here, marrying local knowledge with specialized dating labs and coastal geomorphology expertise. That mix is exactly what complex, dynamic sites demand. Footprints are compelling, but the science has to be even more so.

The Future Landscape

What’s next is method and vigilance. Expect more drones flying low over estuary flats after storms, stitching high‑resolution models that flag suspicious depressions for field checks. Expect portable OSL sampling kits and micro‑core drilling guided by sedimentology, not just convenience. Expect closer ties between archaeologists, iwi kaitiaki, and local councils so that permissions and protocols move at the speed of the tide. And expect training for citizen spotters – fishers, birders, and walkers – so the first photo includes a scale, GPS, and multiple angles. The work is humble, repetitive, and occasionally thrilling.

There are challenges. Sea‑level rise and intensifying storms will both expose and destroy more surfaces, compressing the time window for safe recovery. Tourism pressure on fragile sites is real, and any discovery will draw curious feet to the very place that needs protecting. Funding cycles rarely match the urgency of coastal erosion. Still, the tools are ready, and the partnerships are forming. If Karamea yields footprints, the science to defend them is already on the shelf.

Conclusion

If you walk the Karamea beaches and estuary margins, carry a phone, a coin or key for scale, and curiosity. Photograph any trackway that seems unusual from multiple angles, include the scale in frame, note the time and tide, and avoid stepping on or around the prints. Report finds promptly to the Department of Conservation, your nearest museum, or local iwi authorities, and be prepared to share exact locations privately to prevent damage. Support community groups that restore the Ōtūmahana Estuary and monitor shorebird habitat – healthy sediments are good for both wildlife and archaeology. When you visit, stay on marked routes and respect temporary closures that protect sensitive surfaces. Small, thoughtful actions keep tomorrow’s discoveries intact long enough to become knowledge.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.