On a bright afternoon in the tropics, a green iguana freezes mid-sunbath as a hawk sweeps overhead, ducking a split-second before danger becomes obvious. That lightning-fast flinch doesn’t come from ordinary eyesight but from a curious feature many reptiles carry like a rooftop sensor: a light-detecting organ perched between the eyes. Biologists call it the parietal eye, a window into the brain’s ancient weather station for light, time, and shadow. For decades it puzzled field researchers who noticed its presence but didn’t grasp its quiet power. Now, a wave of careful experiments and comparative studies is revealing how this “third eye” helps iguanas tune their daily rhythms, steer by the sun, and spot aerial threats in time to live another day.

The Hidden Clues

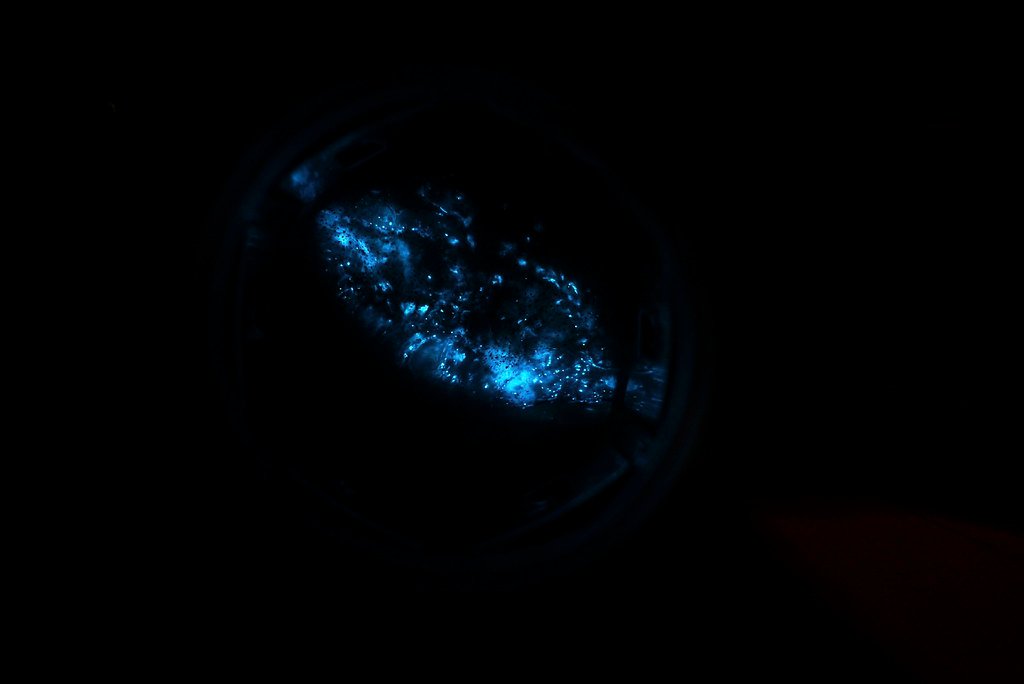

It looks unremarkable at first – a pale, coin-sized scale sitting slightly back from the forehead, easy to miss unless you know where to look. Yet this tiny skylight lets in the kind of information regular eyes often ignore: the rise and fall of daylight, the sudden bloom of a passing shadow, the broad colors of dawn and dusk. Instead of forming images, it captures light as a rhythm, a pulse the brain can translate into action. Think of it as a sundial wired straight into the nervous system, quietly telling the body what time it is and whether something big just crossed the sky. Field observations of iguanas show a consistent pattern: individuals react faster to overhead movement than you’d expect from side-facing eyes alone. The third eye supplies that early warning, trading sharp detail for speed and scope when it matters most.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Early anatomists sketched the strange organ and filed it under curiosities, unsure whether it did much beyond decorate the skull. As microscopy improved, researchers discovered layers of photoreceptor-like cells and a nerve tract running from the crown of the head into the brain’s epithalamus, hinting at a real sensory pathway. In the late twentieth century, behavioral tests on lizards demonstrated that covering the parietal eye disrupted sun-based orientation and altered daily activity patterns, a turning point in understanding its function. Newer electrophysiology and comparative studies expanded the story, showing that the organ responds strongly to broad-spectrum light and sudden dimming – exactly the signals that mark time or warn of a predator’s shadow. What started as an odd scale became a portal into the reptile’s internal clockwork. That shift – from oddity to integral system – is one of the quiet revolutions in modern herpetology.

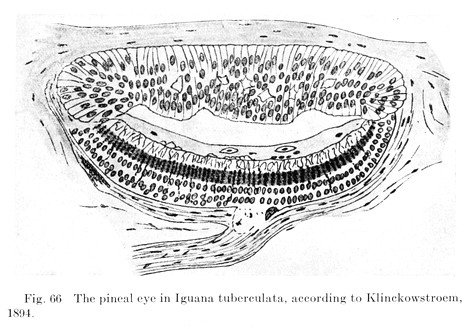

Anatomy: A Skylight to the Brain

In iguanas, the parietal eye sits beneath a translucent scale, with a cup-shaped layer of cells arranged a bit like a primitive retina. There’s no image-forming lens, so clarity is traded for sensitivity to brightness, ultraviolet, and the slow sweep of daylight across the sky. A dedicated nerve connects this surface sensor to deeper brain regions involved in circadian timing and hormonal regulation, forming part of the broader pineal complex. That complex helps govern melatonin release, the sleep–wake hormone that rises and falls with light. Because the organ faces up like a skylight, it samples the most reliable daily signal the environment has to offer. The result is a direct, low-latency channel for light information that complements, rather than competes with, the iguana’s regular eyes.

What Iguanas Do With It

Everyday life for an iguana is a delicate ledger of heat, safety, and timing, and the third eye adds the data that keeps the math honest. By detecting shifts in overhead brightness, iguanas can spot the telltale sweep of a raptor and bolt into cover before sharp-focus vision even locks on. The organ also stabilizes sun-based orientation, helping animals remember where to forage and how to return to safe roosts as the day arcs forward. On the metabolic side, light fed through this channel supports thermoregulation decisions – when to bask, when to shade – so body temperatures stay in the sweet zone for digestion and muscle performance. Captive studies mirror what field biologists see: when the crown sensor is blocked, animals often become sluggish, mistime basking, or show muddled day–night activity. The third eye keeps the schedule honest and the reflexes fast in a world where hesitation costs everything.

The Signal Behind the Sense

Under the skin, the parietal eye translates light into electrical signals through opsin-based photoreceptors, the same family of molecules that make vision possible across vertebrates. When broad-spectrum light or sudden dimming hits those cells, a biochemical cascade opens and closes ion channels, generating pulses that run up the parietal nerve. Brain regions of the pineal complex integrate those signals with information from the regular eyes and the environment, adjusting melatonin rhythms that influence sleep, activity, and body temperature. This pathway is tuned for reliability rather than resolution, emphasizing stable, daily cues that keep physiology synchronized with sunrise and sunset. In practical terms, that means the organ functions like a master dimmer switch, smoothing out peaks and valleys in behavior so the iguana doesn’t waste energy. The elegance lies in its simplicity: a few degrees more light or a fast shadow is all it needs to tip the scales toward action.

Why It Matters

Focusing only on image-forming vision misses a huge part of how animals run their lives, and the iguana’s third eye is a prime example of this blind spot. Traditional studies centered on lenses, retinas, and visual acuity, while the parietal eye shows that perception also means sensing time, trend, and threat without crisp pictures. In medicine and chronobiology, reptiles offer natural experiments in circadian tuning, revealing how light can be routed directly to hormonal systems for stronger, more stable rhythms. For conservationists, the organ is a living gauge of environmental lighting; artificial night light and habitat changes that alter skylight patterns can push these systems out of sync. Even in engineering, designers of low-power sensors study such biology to build devices that respond to change rather than spend energy on continuous high-resolution imaging. The takeaway is simple: sometimes the smartest sensor is the one that ignores detail and listens for rhythm.

The Future Landscape

Next steps in this field hinge on combining gentle, noninvasive neural recordings with precise light environments in both lab and field settings. Portable biologging tags that record light exposure, temperature, and movement can be paired with tiny neural readouts to map how signals flow from the crown to behavior in real time. Advances in reptile genomics and gene expression mapping will clarify which opsins dominate in the parietal eye and how they shift across life stages or habitats. Researchers are also testing how urban skylines and night lighting scramble the organ’s timing cues, a crucial question as iguanas increasingly share space with cities. On the technology side, bio-inspired sensors that detect change over absolute detail could aid drones, environmental monitors, and wildlife cameras that need to respond to motion without burning battery on full-time imagery. The science is moving from description to prediction, turning a mysterious scale into a model system for robust sensing.

Global Perspectives

Iguanas are part of a broader reptile club that includes many lizards and the ancient tuatara, all sporting versions of this light-sensing crown. Some lineages lost the organ as their lifestyles and skulls changed, while others kept and refined it, underscoring its adaptive worth in open habitats with aerial threats. Field ecologists are now comparing populations across islands and urban edges to see how sky exposure and predation pressure sculpt sensitivity. These comparisons help explain why similar organs arise, persist, or fade – a natural experiment written over millions of years and many landscapes. For policy makers, understanding that biology matters when setting lighting rules near nesting trees or riparian corridors where iguanas shelter. A global view turns a single anatomical quirk into a story about evolution’s patience and the environments that make sensory solutions pay off.

Conclusion

You don’t need a lab to make a difference for animals that read the sky as carefully as a clock. Support habitat projects that preserve open canopy corridors with natural light gradients and minimal night glare, especially near known iguana roosts. Back local lighting ordinances that reduce unnecessary nighttime illumination and favor warmer, lower-intensity fixtures that respect wildlife rhythms. If you live in iguana country, keep basking branches and escape routes available in gardens and parks, and report illegal pet releases that complicate conservation. Advocate for field research permits and monitoring programs that track light levels alongside population trends, so policy can follow data. Small choices about light and habitat add up to a world where a quiet sensor on a reptile’s crown can keep doing its ancient job.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.