On a wind-bitten summit in northern Chile, a new eye has opened and the sky has started to move. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory – freshly outfitted with the world’s largest astronomical camera – has shifted from a dream to a working machine, capturing its first on-sky images in 2024 and pushing into an intense phase of commissioning. This is the long-promised start of a 10-year, time-lapse film of the universe, a survey designed to revisit the southern sky every few nights and watch it change. After the 3.2-gigapixel camera was installed in 2024, engineers began dialing in focus, alignment, and thermal stability so each pixel lands exactly where it should. If all goes to plan, full survey operations will ramp up late this year into 2026, and the cosmos will become a living documentary rather than a collection of stills.

The First Frame: When the Sky Started Moving

Here’s the shocker: the first engineering images already look like movie stills from a universe that refuses to sit still. In 2024, the team released early views – star fields laced with structure, nearby nebulas alive with color – and then turned back to the quiet, careful work of making the system sharper, faster, and more repeatable. August brought winter weather on Cerro Pachón and only a handful of clear nights, but even those were enough to refine the optics and test the closed-loop controls that keep the picture steady. You could feel the mood on the mountain shift from anticipation to execution.

I’ve stood in domes where the only sound is the click of cooling fans, and it always feels like a heartbeat before a sprint. Rubin is that sprint – an observatory built to catch the sky in the act.

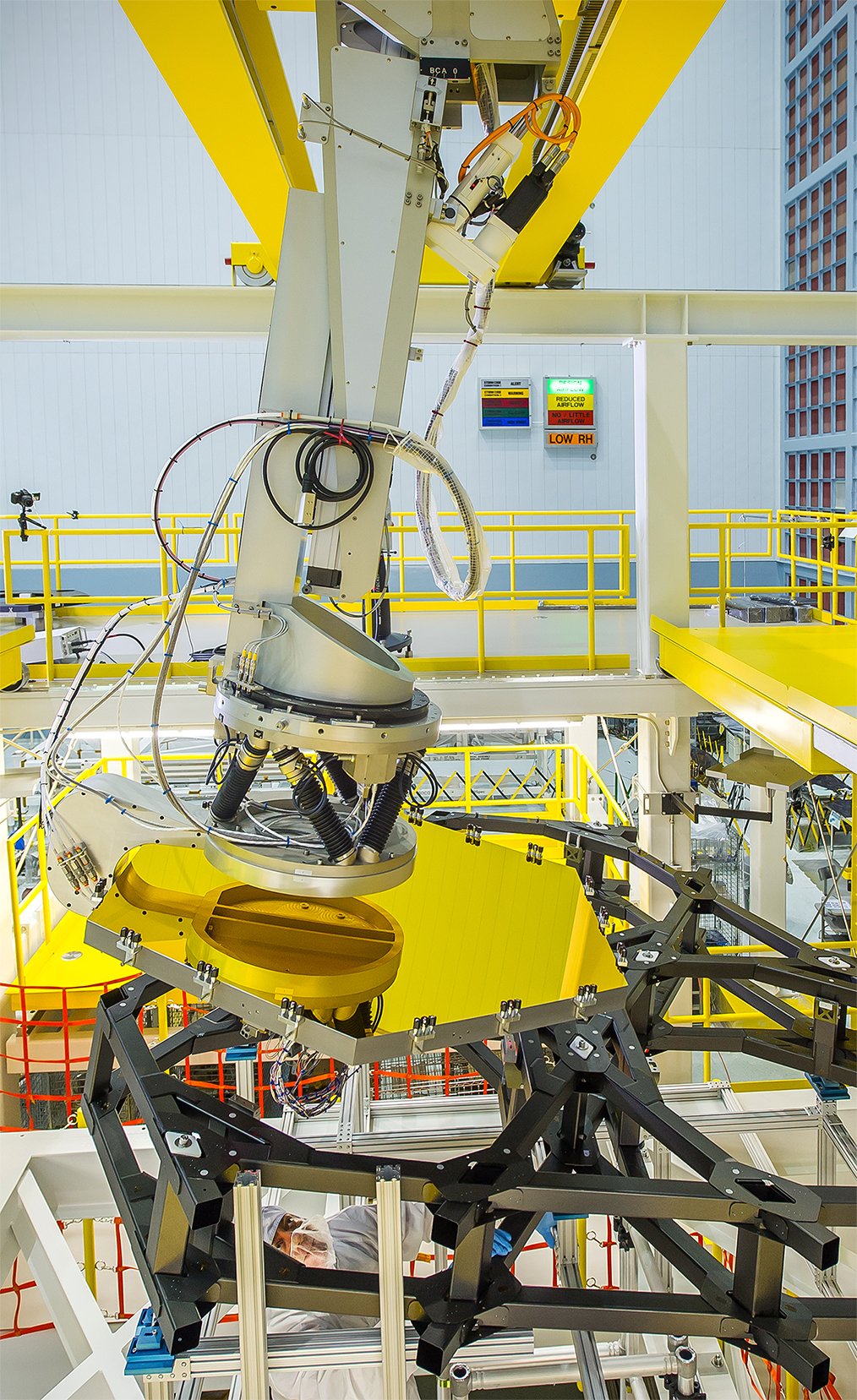

The Machine That Sees Everything

The Simonyi Survey Telescope couples an 8.4-meter mirror to a 3.5-degree field of view, wide enough to swallow seven full moons at once. Its 3.2-gigapixel LSST Camera, about the size of a small car, funnels light onto 189 CCD sensors cooled to cryogenic temperatures so noise stays low and faint objects pop. The shutter is lightning-fast, the filter changer is automated, and the slew-and-settle routine is tuned to jump between targets in moments. It’s a system built for cadence, not vanity shots.

Think of it like a high-speed dashcam for the universe: it patrols the southern sky every three or four nights, frame after frame, building a clean, consistent record of change. That rhythm is everything, because change is where discovery lives.

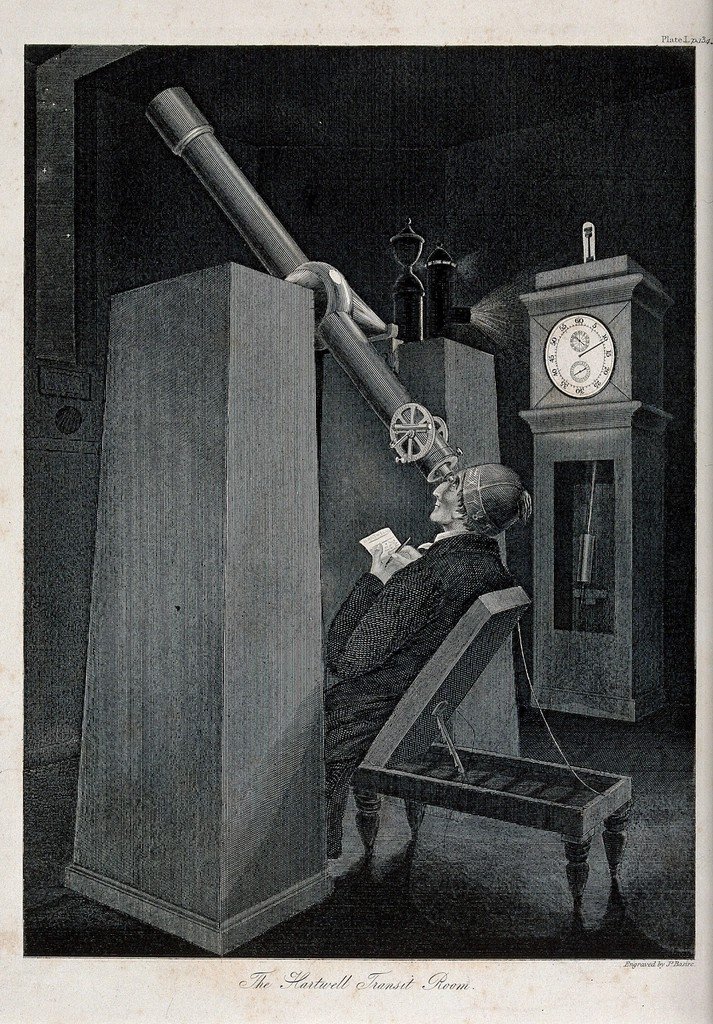

From Ancient Plates to Pixel Thunder: How We Got Here

Astronomy used to be a slow art – glass photographic plates, meticulous notebooks, and patience measured in seasons. The first digital sky surveys sped things up, but they were still snapshots spaced by years, not nights. Pan-STARRS, the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, and surveys with space telescopes made massive leaps, yet none were designed from the ground up to combine wide field, huge depth, and relentless cadence the way Rubin does. The field has been racing toward this moment like a relay, each generation passing the baton of better detectors and smarter software.

Now the baton is a storm of pixels and an alert stream that flags changing objects almost as soon as they shift. It’s the same sky our grandparents traced, but with the volume knob turned up to thunder.

The Hidden Clues in a Billion Galaxies

Rubin’s time-lapse will stitch together the life stories of galaxies, stars, and small bodies that usually slip past unnoticed. Supernovae will be pinned down in their first hours, when their physics is loudest. Quasars will flicker with telltale rhythms that map the engines around black holes. Subtle distortions of galaxy shapes – cosmic weak lensing – will reveal how invisible matter threads the universe.

Even the background is a clue: the distribution and motion of satellite galaxies, the ripples in stellar streams, the demographics of star clusters. Each faint smear becomes a breadcrumb in a story about how structure forms and breaks. The film isn’t just pretty; it’s forensic.

Why It Matters: From Asteroids to Dark Energy

The payoff isn’t abstract. Rubin will spot near‑Earth asteroids that were simply too dim or too fast to catalog reliably before, giving planetary defense a stronger early-warning net. It will time the rise and fall of thousands of supernovae, anchoring distance scales and tightening our grip on the expansion history of the cosmos. With billions of galaxies measured across cosmic time, the survey will test models of dark energy and dark matter with a consistency check hard to game.

Compared with traditional “point-and-stare” telescopes, Rubin trades magnified detail for relentless context, revisiting everything instead of dwelling on a few jewels. That shift – breadth plus cadence – lets scientists connect dots that used to be isolated islands of data. It’s like switching from a single security camera to a citywide grid that never blinks.

- Camera resolution: roughly three-point-two gigapixels across a sixty-centimeter focal plane.

- Field of view: about three and a half degrees, or nearly seven full moons side by side.

- Survey cadence: southern sky revisited roughly every three to four nights for ten years.

- Data scale: petabytes per year, with nightly alerts numbering in the millions.

Global Perspectives: A Planet-Wide Observatory in Spirit

Rubin stands in Chile, but it runs on a global backbone. Data flows from Cerro Pachón to facilities in the United States and out to scientists everywhere, who will sift alerts, trigger follow‑ups, and build catalogs that anyone can query. The project is funded primarily by the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy, yet it leans on international collaboration – from software pipelines to follow‑up telescopes across time zones.

Light pollution and satellite constellations are real challenges, and they don’t respect borders. Mitigation is becoming a diplomatic endeavor, blending regulation, design tweaks, and observing strategies. Rubin’s success will be a case study in how the world shares a dark sky in an age of bright orbiting hardware.

Inside Commissioning: Turning First Light into Science Light

Commissioning is where engineering pictures become scientific measurements, and 2025 has been all about that transformation. After the camera was installed in March, teams spent the southern winter tightening the active optics system, correlating dome temperatures with mirror seeing, and even planning ventilation tweaks to smooth air currents. Clear nights were scarce in August, but that actually stress‑tested the software and operations playbook for when weather turns fickle. The goal is boring excellence: repeatable image quality, precise calibration, and stable throughput.

Only then can you trust the alert stream, the photometry, and the shape measurements that power cosmology and asteroid discovery. In astronomy, confidence is a feature, not a luxury.

The Future Landscape: What Comes After First Light

As full science operations ramp up in the coming years, the big questions pivot from “Can it work?” to “How far can we push it?” Expect smarter real‑time triage that pairs Rubin’s alerts with robotic telescopes worldwide, plus machine‑learning classifiers that learn from their own mistakes. The community will face genuine bottlenecks: compute budgets, storage growth, and the human bandwidth to verify discoveries fast enough to matter for transient phenomena.

Upgrades are already on the whiteboard – software first, hardware later. Improved deblending for crowded fields, better asteroid linking across nights, more robust photometric calibration in variable atmospheric conditions. The global impact could range from more reliable asteroid risk assessments to tighter constraints on cosmic expansion that nudge theory. The universe won’t get simpler; our tools will get sharper.

How You Can Join the Watch

You don’t need a PhD to be part of this. Citizen‑science platforms will host Rubin‑based projects where pattern‑spotting eyes can catch oddballs that algorithms miss, from weird supernova light curves to asteroid trails that bend expectations. Planetary defense groups will lean on volunteers for rapid follow‑ups with backyard telescopes, especially in the southern hemisphere. If you’re a student, open datasets and notebooks will make the survey a training ground for data literacy and discovery.

Simple steps help: support dark‑sky initiatives in your community, advocate for responsible satellite operations, and try a citizen‑science task for fifteen minutes a week. Big science is built from small, steady contributions.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.