When you think about evolution, you probably picture gradual changes over millions of years. But what if I told you that some creatures decided to hit the evolutionary brakes and coast through geological epochs virtually unchanged? Between 250 and 50 million years ago, during the Mesozoic Era and early Cenozoic periods, certain species became evolutionary rebels, refusing to adapt while the world transformed around them. These biological time capsules challenge our understanding of natural selection and survival, proving that sometimes the old ways really are the best ways.

The Coelacanth: The Fish That Time Forgot

Picture this: scientists thought coelacanths had been extinct for 66 million years until a South African museum curator spotted one in a fisherman’s catch in 1938. This “living fossil” has remained virtually unchanged for over 400 million years, sailing through multiple mass extinctions like they were minor inconveniences. The coelacanth’s lobed fins, primitive lung structure, and unique joint in its skull represent evolutionary features that predate most vertebrate innovations.

During the Mesozoic Era, while dinosaurs ruled the land and marine reptiles dominated the seas, coelacanths quietly maintained their ancient body plan. Their slow metabolism and deep-sea habitat provided a stable environment that required minimal evolutionary pressure. Today’s coelacanths are practically identical to their Triassic ancestors, making them one of nature’s most successful evolutionary holdouts.

Ginkgo Trees: Ancient Sentinels of Time

Ginkgo biloba trees were already ancient when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, and they’ve maintained their distinctive fan-shaped leaves for over 200 million years. These remarkable trees witnessed the rise and fall of countless species while stubbornly refusing to evolve new features. Their unique reproductive system, with separate male and female trees, and their distinctive two-lobed leaves haven’t changed since the Jurassic Period.

What makes ginkgos even more fascinating is their incredible resilience. They survived the Permian extinction, the asteroid impact that killed the dinosaurs, and even nuclear radiation in Hiroshima. Their evolutionary strategy of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” has proven remarkably successful across multiple geological eras.

Horseshoe Crabs: The Ultimate Survivors

Horseshoe crabs have been scuttling across ocean floors for 450 million years, making them older than trees, dinosaurs, and even sharks. During the Mesozoic Era, while marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs evolved into increasingly specialized forms, horseshoe crabs maintained their tried-and-true body plan. Their blue blood, compound eyes, and armored shell design haven’t required updates since before vertebrates even existed.

These arthropods survived multiple mass extinctions by sticking to what worked. Their primitive immune system, which uses copper-based blood instead of iron-based hemoglobin, has remained so effective that modern medicine relies on it for testing medical equipment. Sometimes evolutionary conservatism pays off in unexpected ways.

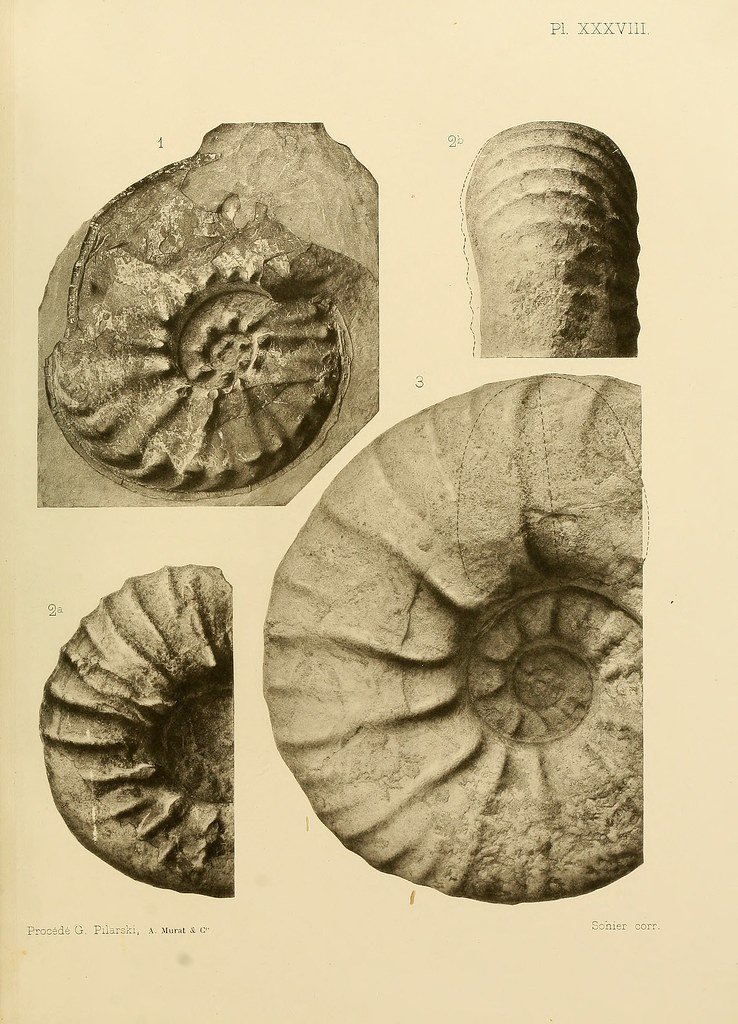

Nautiluses: Spiral Shells Through Deep Time

The nautilus has been perfecting its spiral shell design for over 500 million years, refusing to abandon its successful formula even as its cephalopod relatives evolved into squid, octopuses, and countless extinct varieties. During the Mesozoic Era, while ammonites experimented with increasingly complex shell patterns before going extinct, nautiluses stuck with their simple, elegant chambers. Their jet propulsion system and primitive eyes represent ancient technology that still works perfectly.

These “living submarines” demonstrate that evolutionary success doesn’t always require innovation. Their buoyancy control system, using gas-filled chambers to rise and sink, has remained unchanged since the Paleozoic Era. While other cephalopods developed complex brains and camouflage abilities, nautiluses proved that sometimes the simple approach is the most sustainable.

Tuataras: The Lizard That Isn’t a Lizard

Tuataras might look like ordinary lizards, but they’re actually the last survivors of an ancient reptile order that predates dinosaurs by 50 million years. These New Zealand natives have maintained their primitive features for over 200 million years, including a third eye on top of their heads and teeth fused to their jawbones. During the Mesozoic Era, while their reptilian cousins evolved into dinosaurs, crocodiles, and early mammals, tuataras remained virtually unchanged.

Their extremely slow metabolism and growth rate might seem like evolutionary disadvantages, but these traits have allowed them to survive in environments where faster-living species would struggle. Tuataras can live over 100 years and don’t reach sexual maturity until they’re 20, representing an evolutionary strategy focused on longevity rather than rapid reproduction.

Crocodilians: Perfected Predators

Crocodiles and alligators have been apex predators for over 200 million years, and their basic body plan hasn’t required significant updates since the Triassic Period. While dinosaurs evolved into birds and mammals diversified into countless forms, crocodilians maintained their successful semi-aquatic predator design. Their powerful jaws, armored skin, and ambush hunting strategy proved so effective that evolution saw no need for major modifications.

During the Mesozoic Era, some crocodilian relatives experimented with different lifestyles, including fully marine forms and even herbivorous species. However, the traditional crocodile model survived multiple mass extinctions while these evolutionary experiments went extinct. Their ability to survive months without food and their incredibly efficient hunting strategy have made them living examples of evolutionary perfection.

Lamprey Eels: Ancient Parasites Persist

Lampreys have been latching onto larger fish with their circular, tooth-filled mouths for over 360 million years, making them one of the oldest vertebrate groups still alive today. These primitive creatures lack paired fins, jaws, and scales, retaining features that were common before the evolution of modern fish. During the Mesozoic Era, while bony fish diversified into thousands of species, lampreys maintained their parasitic lifestyle with minimal changes.

Their larval stage, which involves burrowing in river sediments and filter-feeding for several years, represents an ancient developmental pattern that predates most vertebrate innovations. Lampreys’ simple nervous system and primitive sensory organs have remained effective enough to support their survival through multiple geological epochs.

Cycads: Palm-Like Plants from the Dinosaur Age

Cycads dominated Mesozoic landscapes alongside dinosaurs, and their crown-like appearance and seed-bearing cones haven’t changed significantly in 280 million years. These plants were already ancient when flowering plants began their evolutionary revolution, yet they maintained their primitive reproductive systems and slow growth patterns. During the Jurassic Period, cycads were so common that the era is sometimes called the “Age of Cycads.”

Their relationship with specialized pollinating insects represents one of the oldest plant-animal partnerships still functioning today. While flowering plants developed countless innovations to attract pollinators, cycads stuck with their original beetle-pollination system. Their extremely slow growth and long lifespans represent an evolutionary strategy that prioritizes stability over rapid adaptation.

Sharks: Ocean Rulers Since Ancient Times

Sharks have been patrolling Earth’s oceans for over 400 million years, and their basic body plan has remained remarkably consistent throughout this vast timespan. While marine reptiles like ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs evolved during the Mesozoic Era only to go extinct, sharks maintained their successful predatory design. Their cartilaginous skeletons, multiple rows of replaceable teeth, and hydrodynamic bodies represent evolutionary solutions that have stood the test of time.

During the age of dinosaurs, sharks shared the oceans with massive marine reptiles, yet they outlived these spectacular creatures by sticking to their proven formula. Their ability to sense electrical fields, detect minute chemical traces, and maintain perfect buoyancy has required no major updates for hundreds of millions of years. Modern sharks are essentially swimming time machines, carrying ancient wisdom in their streamlined bodies.

Brachiopods: Filter-Feeders That Refused to Quit

Brachiopods were incredibly common during the Paleozoic Era, and while they lost their dominance to clams and other bivalves, some species maintained their ancient body plan for over 500 million years. These filter-feeding creatures attach to the seafloor and pump water through their shells to capture food particles, using the same technique their Cambrian ancestors perfected. During the Mesozoic Era, while marine ecosystems underwent massive changes, brachiopods quietly continued their time-tested lifestyle.

Their unique shell structure, with two valves of different sizes, and their specialized feeding apparatus represent evolutionary innovations that were already ancient when dinosaurs first appeared. Modern brachiopods like Lingula are virtually identical to specimens found in rocks over 400 million years old, making them some of the most evolutionarily conservative animals on Earth.

Velvet Worms: Soft-Bodied Time Travelers

Velvet worms have been crawling through moist environments for over 500 million years, maintaining their soft, segmented bodies and unique slime-squirting hunting technique throughout this incredible timespan. These bizarre creatures represent a evolutionary link between arthropods and annelids, preserving primitive features that disappeared in most other animal groups. During the Mesozoic Era, while insects underwent massive diversification, velvet worms maintained their ancient body plan with minimal modifications.

Their method of capturing prey by shooting streams of adhesive slime represents one of the oldest hunting strategies still in use today. Velvet worms’ simple respiratory system, using numerous small openings called spiracles, and their primitive nervous system have remained virtually unchanged since the Cambrian explosion. They’re living representatives of what early terrestrial animals might have looked like.

Sturgeon: Ancient Giants of Freshwater

Sturgeon have been swimming in Earth’s rivers and seas for over 200 million years, making them one of the oldest fish groups still alive today. These massive fish have maintained their cartilaginous skeletons, rows of bony plates called scutes, and primitive gill covers throughout the Mesozoic Era and beyond. While bony fish evolved countless innovations, sturgeon stuck with their successful bottom-feeding lifestyle and ancient body plan.

Their extremely long lifespans and delayed sexual maturity represent evolutionary strategies that prioritize individual survival over rapid reproduction. Some sturgeon species can live over 100 years and don’t reproduce until they’re decades old, a approach that has allowed them to survive multiple environmental changes that eliminated faster-reproducing species.

Cockroaches: The Ultimate Adapters

Cockroaches have been scuttling across Earth’s surfaces for over 300 million years, and their basic body plan has remained remarkably consistent throughout this vast period. During the Mesozoic Era, while other insect groups underwent massive diversification, cockroaches maintained their successful omnivorous lifestyle and hardy constitution. Their flat bodies, long antennae, and rapid reproductive cycle represent evolutionary solutions that have proven incredibly durable.

These insects survived the extinction event that killed the dinosaurs and have thrived in environments ranging from tropical forests to urban apartments. Their ability to eat almost anything, survive without their heads for weeks, and reproduce rapidly has made them one of evolution’s most successful holdouts. Modern cockroaches are essentially living fossils with wings.

Dragonflies: Masters of Flight Since Ancient Times

Dragonflies have been perfecting their aerial hunting skills for over 300 million years, and their flight capabilities remain unmatched in the animal kingdom. During the Mesozoic Era, while birds were just beginning to evolve powered flight, dragonflies had already mastered complex aerial maneuvers using their four independently-moving wings. Their compound eyes, which can detect movement and colors invisible to humans, represent ancient sensory technology that modern engineers still struggle to replicate.

These ancient aviators can fly backwards, hover in place, and achieve flight speeds that would make modern helicopters envious. Their aquatic larval stage and aerial adult lifestyle represent an evolutionary strategy that has remained successful for hundreds of millions of years. Dragonflies are living proof that sometimes the first solution really is the best solution.

Conclusion: Evolution’s Greatest Lesson

These ten remarkable creatures teach us that evolutionary success isn’t always about constant change and adaptation. Sometimes the most successful strategy is to find what works and stick with it, even when the world transforms around you. From the depths of ancient oceans to the canopies of prehistoric forests, these living fossils have maintained their ancient wisdom while countless other species experimented their way to extinction.

Their stories remind us that nature values both innovation and conservation, change and stability. These evolutionary holdouts survived multiple mass extinctions, climate changes, and competitive pressures by perfecting sustainable lifestyles rather than chasing every new evolutionary trend. In a world obsessed with constant change and improvement, perhaps we can learn something from these ancient survivors about the power of staying true to what works.

What does it tell us about life itself that some of Earth’s most successful creatures are also its most ancient?