Imagine dedicating your entire career to studying ancient life, only to discover that your greatest find was actually a carefully constructed hoax. Or worse, realizing that decades of scientific understanding were built on a fundamental misinterpretation of fossil evidence. Welcome to the messy, controversial, and surprisingly human world of paleontology – where even the most respected scientists can fall victim to deception, wishful thinking, and simple mistakes.

The Piltdown Man Hoax: Science’s Most Embarrassing Fraud

For over 40 years, Piltdown Man stood as proof that human evolution began in England, not Africa. The fossils, discovered in 1912 by Charles Dawson, seemed to show the perfect “missing link” between apes and humans. British scientists were thrilled – finally, they had their own evolutionary superstar to rival the Neanderthals found in Germany.

The truth was devastating when it emerged in 1953. The skull was actually a medieval human cranium artificially aged and combined with the jaw of an orangutan. The teeth had been filed down to appear more human-like, and the entire assemblage had been chemically treated to look ancient. The hoax had fooled some of the world’s most brilliant minds for decades.

What makes this fraud particularly shocking is how it shaped scientific thinking for nearly half a century. Textbooks were rewritten, evolutionary trees were redrawn, and countless research hours were wasted chasing false leads. The Piltdown deception reminds us that even peer review and scientific consensus can be spectacularly wrong.

Archaeoraptor: The Feathered Dinosaur That Never Was

In 1999, National Geographic proudly announced the discovery of Archaeoraptor, a spectacular fossil that seemed to prove the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds. The fossil showed a dinosaur body with perfectly preserved feathers – exactly what scientists had been hoping to find. The media went wild, and the specimen was hailed as one of the most important paleontological discoveries of the century.

Within months, the celebration turned to humiliation. Chinese scientists revealed that Archaeoraptor was actually a clever composite of two different fossils – a bird’s body glued to a dinosaur’s tail. The forgery had been created by fossil dealers looking to maximize their profits by combining lesser specimens into something more spectacular.

The scandal highlighted the growing problem of commercial fossil hunting in China, where farmers and dealers often “enhance” their finds to fetch higher prices. It also exposed how eager scientists and journalists can be to announce groundbreaking discoveries before proper verification. The incident led to stricter authentication protocols and a more cautious approach to sensational fossil claims.

Nebraska Man: Building a Human From a Single Tooth

Sometimes the most spectacular mistakes come from the smallest evidence. In 1922, paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn discovered a single molar in Nebraska and boldly declared it belonged to an early human ancestor. Based on this lone tooth, he constructed an entire species called Hesperopithecus haroldcookii, complete with detailed illustrations of what this “Nebraska Man” might have looked like.

The scientific community was divided, but the discovery gained international attention as potential proof of human evolution in North America. Detailed artistic reconstructions showed a primitive human family living on the American plains millions of years ago. The tooth became the center of heated debates about human origins and evolution.

The embarrassment was complete when further excavations revealed more teeth and jaw fragments that clearly belonged to an extinct species of pig. Years of scientific speculation, academic arguments, and public fascination had all been based on a single pig tooth. The incident became a cautionary tale about drawing sweeping conclusions from minimal evidence.

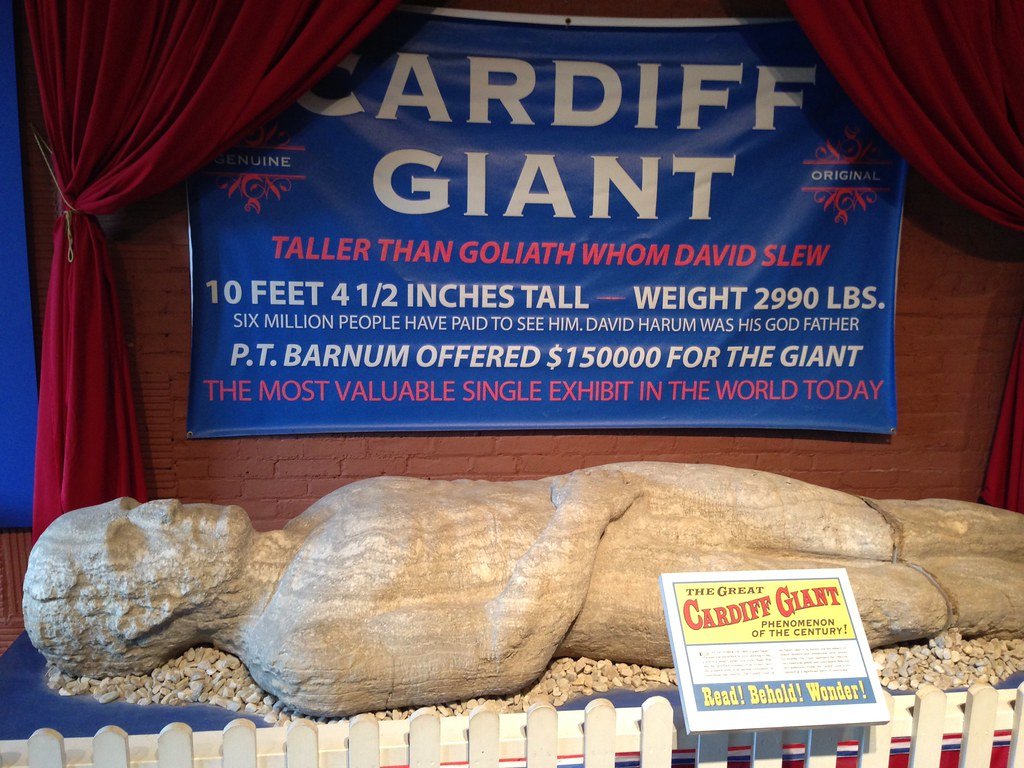

The Cardiff Giant: America’s Greatest Archaeological Hoax

In 1869, workers digging a well in Cardiff, New York, unearthed what appeared to be a 10-foot-tall petrified man. The discovery sent shockwaves through the scientific community and the public alike. Was this proof of biblical giants? Evidence of a lost ancient civilization? Thousands of people paid to see the “Cardiff Giant,” and experts debated its authenticity.

The truth was far more mundane and clever. The giant was actually a carved gypsum statue, created by atheist George Hull to fool his fundamentalist relatives who believed in biblical literalism. Hull had commissioned the statue in Chicago, aged it with acid and sand, and secretly buried it on his cousin’s farm. The hoax was designed to expose the gullibility of religious believers.

What made the Cardiff Giant particularly successful was how it exploited the cultural tensions of the time. Religious Americans wanted to believe in biblical giants, while others were fascinated by the possibility of ancient civilizations. The hoax revealed how easily people could be deceived when presented with evidence that confirmed their existing beliefs.

Brontosaurus: The Dinosaur That Didn’t Exist

For over a century, Brontosaurus was one of the most famous dinosaurs in popular culture. Children played with Brontosaurus toys, museums displayed Brontosaurus skeletons, and the gentle giant became synonymous with prehistoric life. There was just one problem – Brontosaurus never actually existed as a distinct species.

The confusion began in the 1870s during the heated “Bone Wars” between paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. In their rush to outdo each other, Marsh hastily named several dinosaur species, including Brontosaurus in 1879. However, closer examination revealed that Brontosaurus was actually the same animal as Apatosaurus, which had been named two years earlier.

Scientific naming rules dictate that the first valid name takes precedence, so Brontosaurus should have been dropped. However, the name had become so popular that it persisted in museums and popular culture for decades. It wasn’t until 2015 that some scientists argued for reinstating Brontosaurus as a separate genus, though the debate continues to this day.

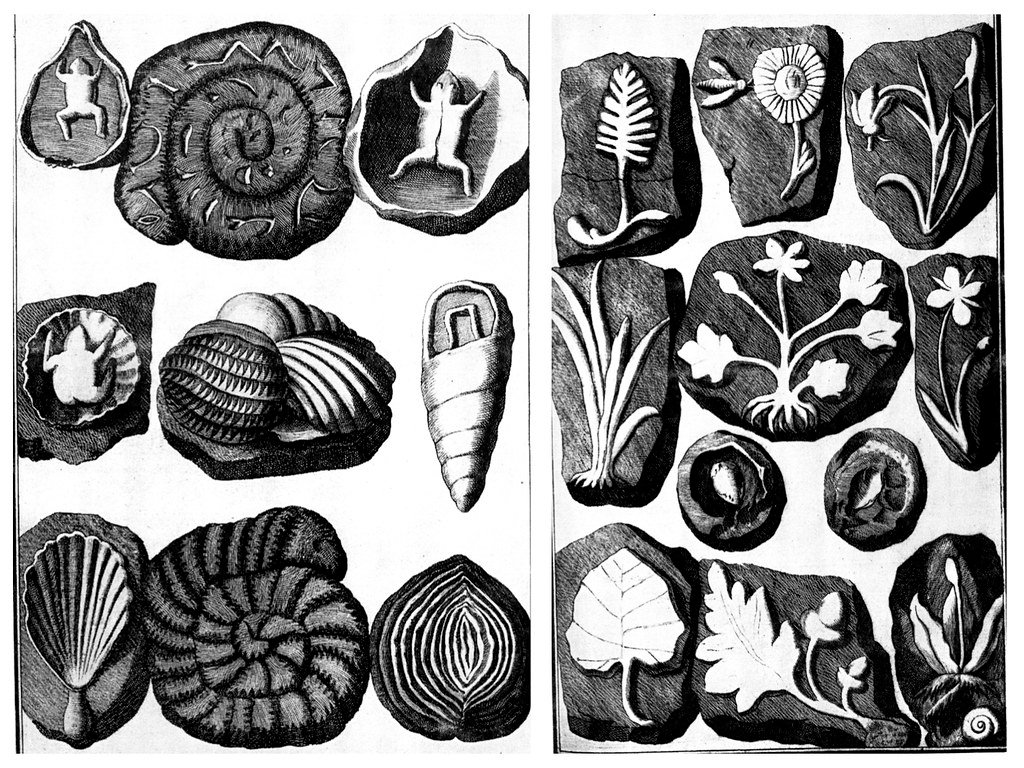

The Lying Stones of Würzburg: When Students Fool Their Professor

In 1725, respected professor Johann Bartholomew Adam Beringer began finding extraordinary fossils near Würzburg, Germany. These weren’t ordinary fossils – they depicted Hebrew letters, Arabic characters, and even astronomical symbols. Beringer was convinced he had discovered proof that fossils were created directly by God as divine messages embedded in stone.

Beringer published his findings in a book called “Lithographiae Wirceburgensis,” complete with detailed illustrations of the remarkable specimens. The academic world was both fascinated and skeptical. How could ancient stones contain complex symbols and writing? The mystery deepened when Beringer found fossils bearing his own name.

The cruel truth emerged when Beringer discovered that his own students and colleagues had been carving fake fossils to humiliate him. They had been secretly burying their creations where Beringer conducted his fieldwork. The hoax destroyed his reputation and financial security, as he had spent his life savings publishing his book. The incident became known as “Beringer’s Lying Stones” and serves as a reminder that scientific fraud can come from the most unexpected sources.

The Calaveras Skull: Gold Rush Era Paleontology Gone Wrong

During California’s Gold Rush in 1866, miners claimed to have discovered a human skull deep in ancient rock layers that should have predated human presence in North America by millions of years. The Calaveras Skull, as it became known, suggested that humans had lived in California far longer than previously thought. If authentic, it would have revolutionized understanding of human migration and evolution.

The skull was examined by prominent geologist Josiah Whitney, who declared it genuine and ancient. The find sparked intense debate about human origins and the age of human presence in the Americas. Some scientists saw it as proof of extremely ancient human civilizations, while others remained skeptical of the extraordinary claims.

Later investigations revealed the skull was actually a recent Native American burial that had been deliberately planted in the mine. The hoax was apparently the work of miners who wanted to fool the scientific community and gain notoriety. The incident highlighted the dangers of accepting extraordinary claims without proper archaeological context and rigorous verification.

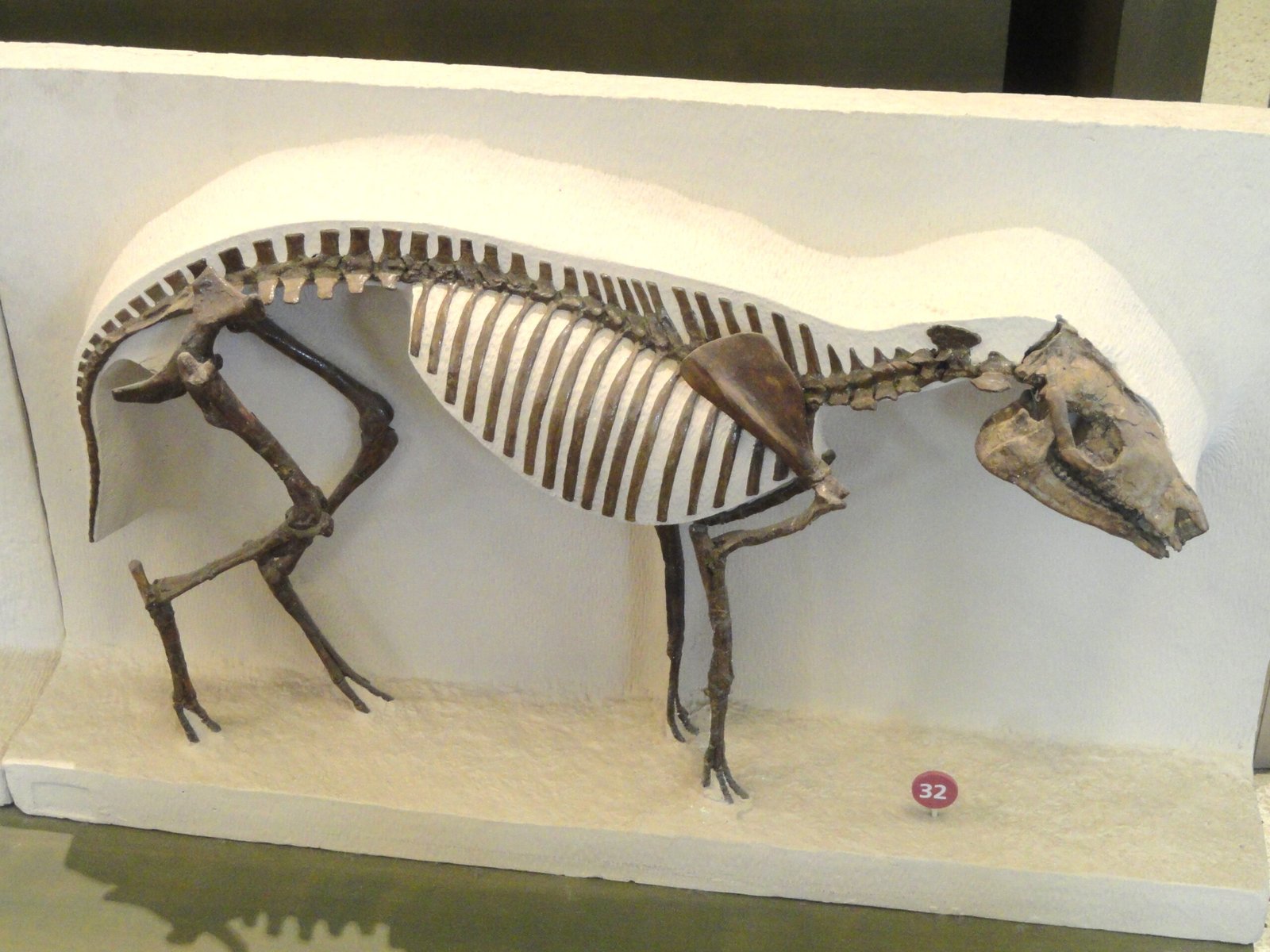

Pentaceratops: The Five-Horned Dinosaur That Had Four

When paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn first described Pentaceratops in 1923, he counted five horns on the dinosaur’s skull and confidently named it “five-horned face.” The massive ceratopsian dinosaur seemed to represent a unique evolutionary development among horned dinosaurs. For decades, Pentaceratops was classified as having the most horns of any known dinosaur.

Modern reexamination of the fossils revealed an embarrassing counting error. What Osborn had identified as additional horns were actually enlarged cheek bones that all ceratopsian dinosaurs possessed. Pentaceratops actually had the standard four horns found in most of its relatives – two brow horns and two cheek projections.

The mistake persisted for decades because few scientists bothered to reexamine the original specimens. It wasn’t until advanced imaging techniques and comparative anatomy studies revealed the true nature of the skull features. The error demonstrates how even basic observations can be wrong when viewed through the lens of expectation and limited comparative knowledge.

The Bone Wars: When Competition Corrupts Science

The late 1800s saw one of paleontology’s most shameful episodes: the Bone Wars between Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. These two prominent paleontologists turned scientific rivalry into personal warfare, complete with espionage, theft, and deliberate sabotage. Their bitter competition led to numerous misidentifications, hasty publications, and outright fraud.

Both men were so eager to outdo each other that they often published descriptions of new species based on incomplete remains. They would rush to name new dinosaurs from single bones or partial skeletons, leading to confusion that persists to this day. Many “different” dinosaur species from this era were actually the same animal described by competing researchers.

The rivalry became so intense that they hired armed guards to protect their dig sites and spies to infiltrate each other’s expeditions. Workers were bribed to steal fossils, and valuable specimens were sometimes destroyed rather than allow rivals to study them. The scientific damage from their feud took decades to untangle, with numerous species having to be renamed or reclassified when cooler heads prevailed.

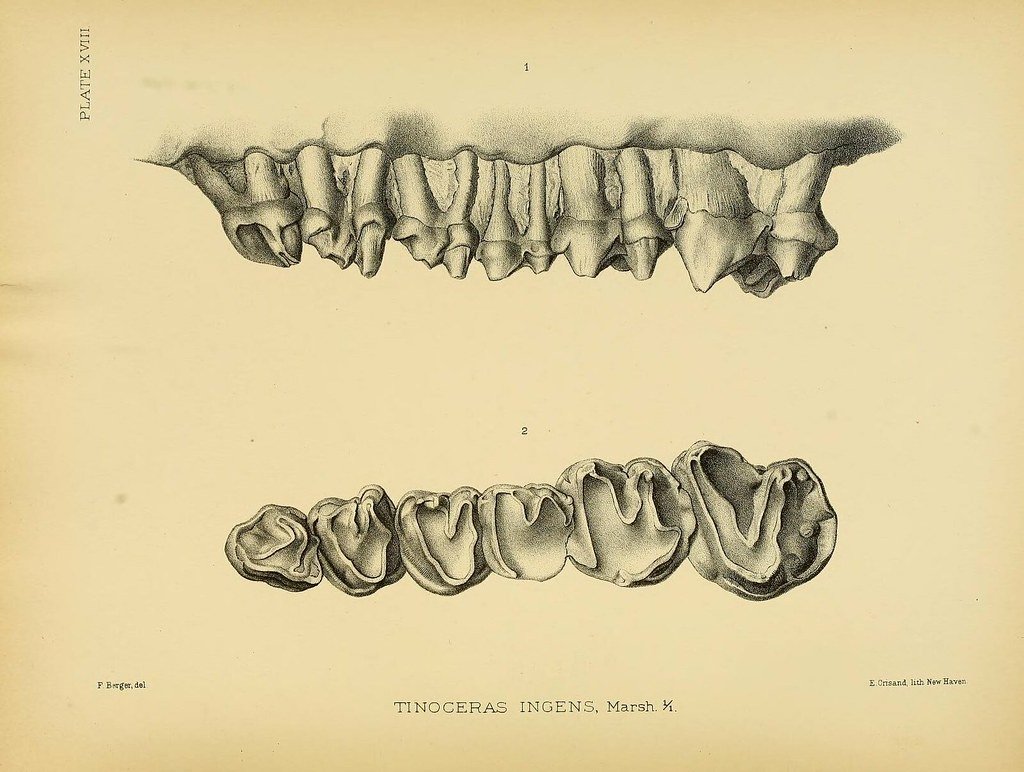

Eohippus: The Tiny Horse That Wasn’t

For generations, biology textbooks featured Eohippus as the perfect example of evolutionary progression. This tiny, four-toed “dawn horse” was presented as the clear ancestor of modern horses, showing how evolution gradually transformed small forest creatures into large grassland runners. The evolutionary series from Eohippus to modern horses became one of the most cited examples of evolutionary theory in action.

Modern paleontologists have largely abandoned this linear progression model. Eohippus, now properly called Hyracotherium, was not actually a direct ancestor of horses but rather a side branch of the evolutionary tree. The traditional “horse evolution” series oversimplified a complex branching pattern of related species, many of which were evolutionary dead ends.

The mistake highlights how scientists can impose false patterns on fossil evidence when they’re looking for simple, linear progressions. Evolution is actually a messy, branching process with many false starts and dead ends. The corrected understanding of horse evolution is far more complex and interesting than the oversimplified textbook version that dominated education for decades.

The Piltdown Chicken: Modern Fossil Fraud in China

The late 1990s saw a surge in spectacular fossil discoveries from China, including numerous feathered dinosaurs that revolutionized understanding of bird evolution. However, this bonanza also attracted commercial fossil hunters who weren’t above creating fake specimens to meet international demand. The trade in fake fossils became so sophisticated that even experienced paleontologists were fooled.

One of the most notorious examples involved composite fossils created by gluing together parts of different animals. Dealers would combine bird and dinosaur fossils to create spectacular “missing links” that fetched high prices from museums and collectors. These forgeries were often so skillfully made that they required advanced imaging techniques to detect the fraud.

The problem became so widespread that scientists began referring to questionable specimens as “Piltdown chickens” – a reference to the famous Piltdown Man hoax. The situation forced the paleontological community to develop new authentication methods and highlighted the corrupting influence of commercial fossil trading on scientific research.

Megalosaurus: The First Dinosaur That Wasn’t What It Seemed

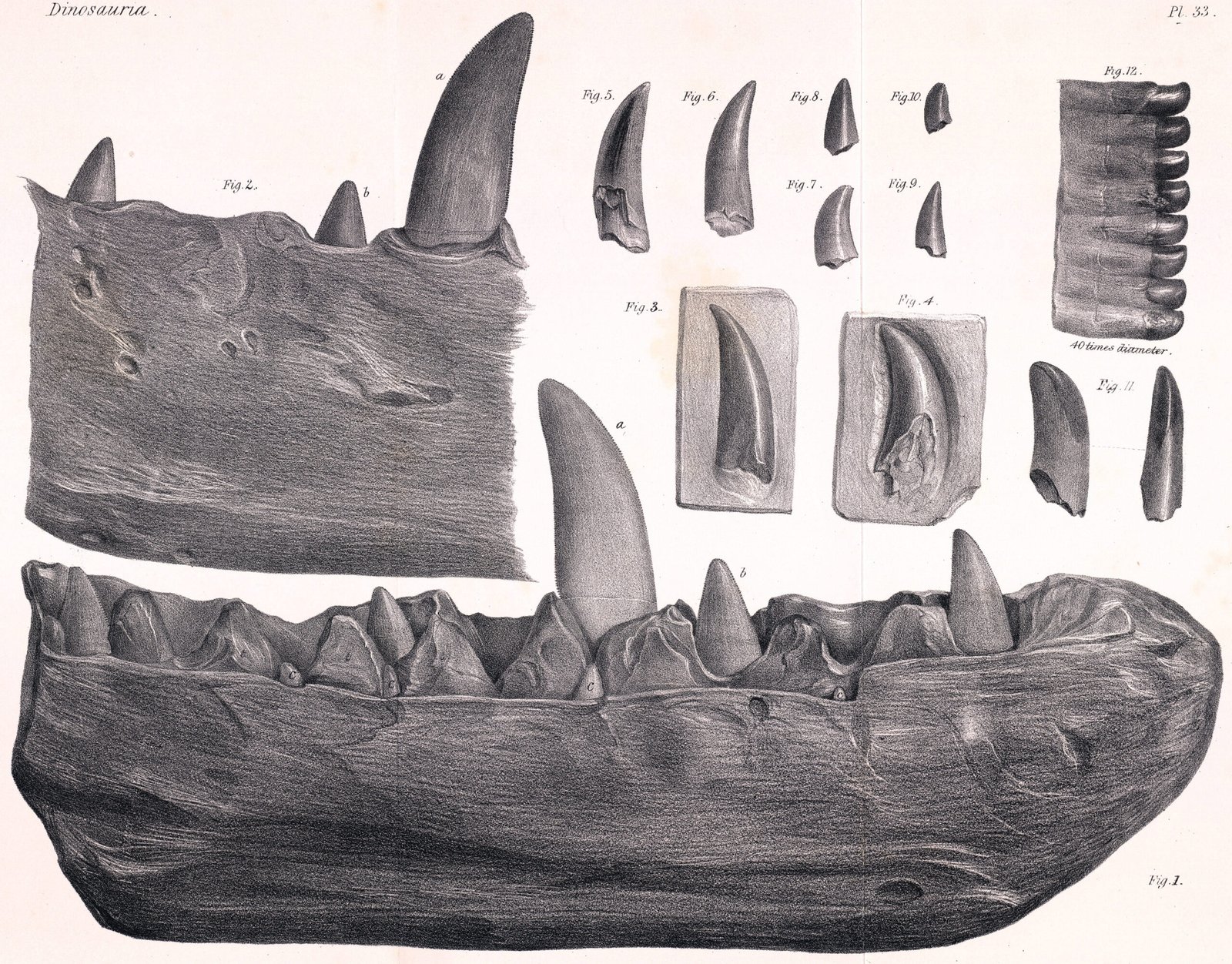

In 1824, William Buckland described Megalosaurus as the first dinosaur to receive a scientific name, though the term “dinosaur” wouldn’t be coined for another 18 years. Based on fragmentary jaw bones and teeth, Buckland reconstructed Megalosaurus as a giant lizard-like creature that walked on four legs. His description launched the scientific study of dinosaurs and captured public imagination.

As more complete dinosaur fossils were discovered, it became clear that Buckland’s reconstruction was fundamentally wrong. Megalosaurus was actually a bipedal predator, not a quadrupedal lizard. The original description was based on such limited material that almost every detail about the animal’s appearance and behavior had to be revised as better fossils emerged.

The Megalosaurus mistake illustrates how incomplete fossil evidence can lead to wildly incorrect reconstructions. Early paleontologists had no context for understanding dinosaur anatomy and often compared them to modern reptiles. It took decades of additional discoveries to reveal the true nature of these ancient animals and correct the misconceptions that arose from incomplete evidence.

The Dinosaur Extinction Asteroid: A Theory That Almost Wasn’t

When Luis and Walter Alvarez first proposed in 1980 that an asteroid impact killed the dinosaurs, the scientific community was largely skeptical. The idea seemed too dramatic, too much like science fiction. Most paleontologists favored gradual climate change or volcanic activity as explanations for the mass extinction event 66 million years ago.

The Alvarez team faced years of criticism and ridicule from established paleontologists who viewed the impact theory as sensationalist. Many scientists dismissed the evidence of iridium layers in rock formations as coincidental or irrelevant. The resistance was so strong that some researchers’ careers were damaged by association with the “asteroid hypothesis.”

The discovery of the Chicxulub crater in the 1990s finally provided the smoking gun that convinced skeptics. The impact theory went from fringe science to mainstream acceptance within a decade. The episode demonstrates how scientific establishment can resist revolutionary ideas, even when supported by solid evidence, and how paradigm shifts in science can take decades to achieve acceptance.

Sue the T. rex: Legal Battles Over Fossil Ownership

The discovery of “Sue,” the most complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton ever found, should have been a triumph for paleontology. Instead, it sparked a legal battle that lasted eight years and involved federal agents, courts, and multiple claimants. The case raised fundamental questions about who owns fossils and how they should be studied and preserved.

The controversy began when fossil hunter Sue Hendrickson found the skeleton on private land in South Dakota in 1990. The land owner, the fossil hunters, and the federal government all claimed ownership rights. FBI agents eventually seized the skeleton, and it sat in storage for years while lawyers fought over its fate.

The legal battle highlighted the complex issues surrounding fossil ownership and the growing commercialization of paleontology. Many important fossils end up in private collections rather than museums, making them unavailable for scientific study. The Sue case led to new regulations about fossil collecting on public lands and raised awareness about the importance of keeping significant fossils in public institutions.

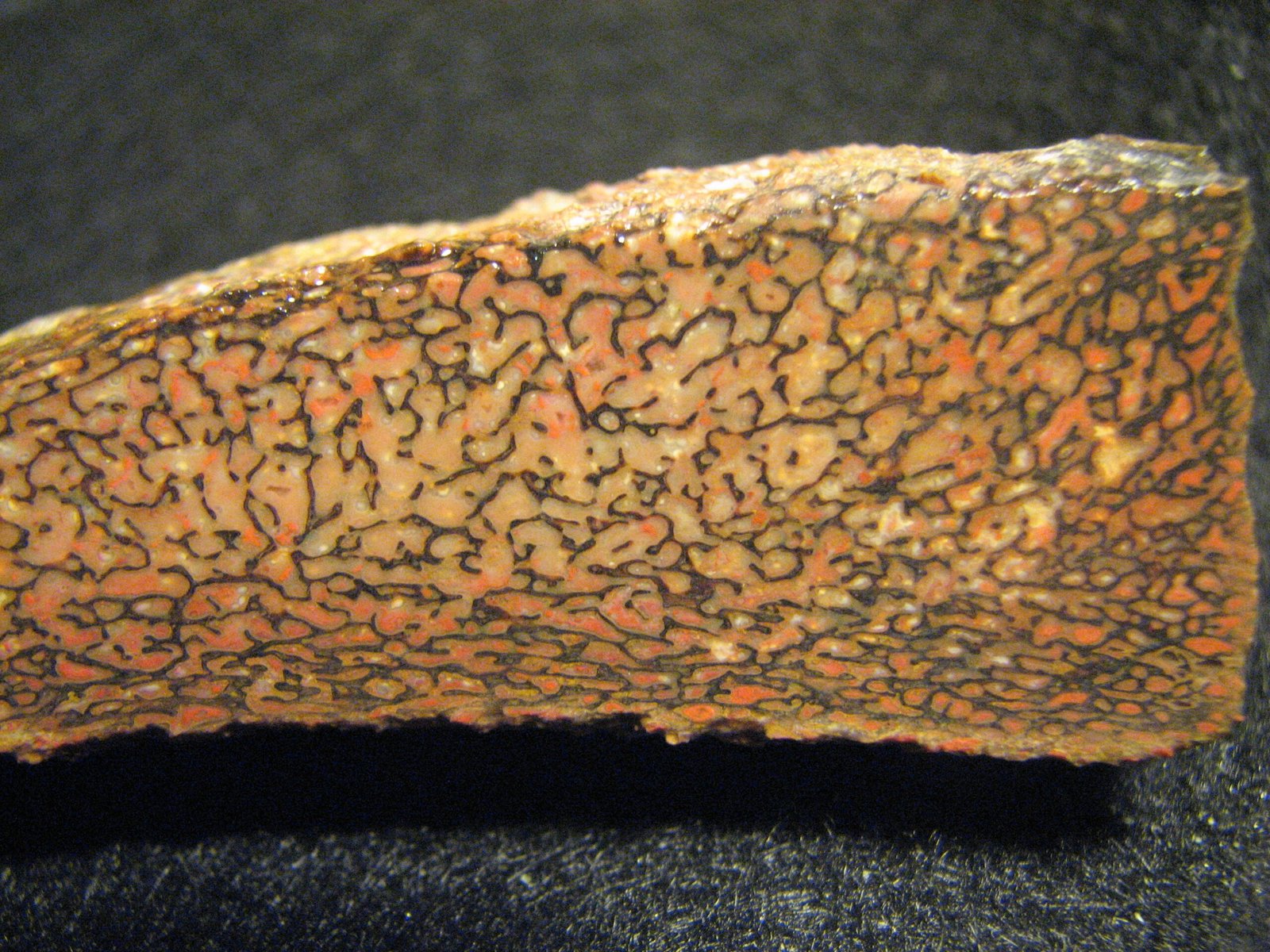

Dinosaur Soft Tissue: The Discovery That Shocked Science

In 2005, Mary Schweitzer announced one of the most controversial discoveries in paleontology: soft tissue preservation in 68-million-year-old dinosaur bones. The finding challenged everything scientists thought they knew about fossilization and organic preservation. Many experts initially dismissed the results as contamination or misidentification.

The discovery of blood vessels, proteins, and even possible DNA fragments in T. rex bones seemed impossible according to conventional understanding of molecular decay. Critics argued that no organic material could survive for tens of millions of years. The controversy split the paleontological community between those who accepted the evidence and those who demanded alternative explanations.

Subsequent research has confirmed soft tissue preservation in multiple dinosaur specimens, revolutionizing understanding of fossilization processes. The discovery opened new avenues for studying dinosaur biology and evolution. However, it also demonstrates how scientific orthodoxy can initially reject genuinely revolutionary findings that challenge established paradigms.

The Feathered Dinosaur Revolution: Rewriting Prehistoric Life

The discovery of feathered dinosaurs in China during the 1990s completely transformed understanding of dinosaur appearance and behavior. For over a century, dinosaurs had been portrayed as scaly, reptilian creatures. The revelation that many dinosaurs were actually covered in feathers forced scientists to reconsider everything from dinosaur metabolism to their evolutionary relationship with birds.

The first feathered dinosaur discoveries were initially met with skepticism and accusations of fraud. Many paleontologists found it difficult to abandon their mental image of scaly dinosaurs. The specimens were so different from previous finds that some scientists questioned whether they were actually dinosaurs at all.

As more feathered dinosaur fossils emerged, resistance crumbled and gave way to excitement. The discoveries revealed that feathers evolved long before flight, possibly for insulation or display purposes. Museums worldwide had to update their dinosaur exhibits, and popular culture slowly began to embrace the new image of colorful, feathered prehistoric creatures. The revolution shows how dramatic new evidence can completely overturn established scientific understanding.

Conclusion: Learning From Our Mistakes

The history of paleontology is littered with embarrassing mistakes, deliberate frauds, and revolutionary discoveries that were initially rejected. These episodes reveal the deeply human nature of scientific endeavor – complete with ambition, rivalry, bias, and the occasional dose of wishful thinking. Yet perhaps most importantly, they demonstrate science’s capacity for self-correction and growth.

Every major paleontological mistake has ultimately led to improved methods, better verification procedures, and deeper understanding. The Piltdown Man hoax resulted in more rigorous authentication protocols. The Bone Wars taught scientists the importance of collaboration over competition. Modern fossil fraud has driven the development of sophisticated imaging techniques that can detect even the most skillful forgeries.

The mistakes of the past remind us that science is not a collection of unchanging facts but a dynamic process of discovery, error, and correction. Today’s certainties may become tomorrow’s embarrassing misconceptions. The key is maintaining healthy skepticism, rigorous testing, and the intellectual humility to admit when we’re wrong. After all, the greatest discoveries often come from recognizing that our previous understanding was incomplete or entirely incorrect.

What fascinates you more – the audacity of the hoaxers or the resilience of science in eventually exposing the truth?