Sometimes the most groundbreaking scientific discoveries happen when researchers least expect them. A spilled chemical, a forgotten experiment, or a simple mistake can lead to revolutionary breakthroughs that change our understanding of the world. These accidental discoveries remind us that science isn’t always about following rigid protocols – sometimes it’s about being observant enough to notice when something unexpected happens.

Throughout history, countless scientific advances have emerged from pure chance encounters. From life-saving medications to revolutionary technologies, many of our most important discoveries came about because someone was curious enough to investigate an anomaly rather than dismiss it as a failure.

The Sweet Mistake That Changed Chemistry Forever

In 1879, Constantin Fahlberg was working late in his laboratory at Johns Hopkins University, researching coal tar derivatives. After a particularly long day of experiments, he rushed home without washing his hands properly. During dinner, he noticed that his bread tasted unusually sweet.

Fahlberg realized the sweetness was coming from his unwashed hands, which had been contaminated with chemicals from his lab work. He rushed back to his laboratory and began systematically tasting different compounds he had been working with that day. This led him to identify saccharin, the first artificial sweetener.

The discovery revolutionized the food industry and provided a sugar substitute for diabetics. Today, saccharin is still widely used in diet products and sugar-free foods worldwide. What started as poor laboratory hygiene became one of the most commercially successful accidental discoveries in chemistry.

A Moldy Petri Dish That Saved Millions

Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin in 1928 happened because he was notoriously messy in his laboratory. Before leaving for vacation, Fleming had stacked several petri dishes containing Staphylococcus bacteria cultures in his lab sink. When he returned, he found that one dish had been contaminated with mold.

Instead of immediately discarding the contaminated sample, Fleming noticed something remarkable. The bacteria around the mold had been killed, while bacteria further away remained unaffected. This observation led him to investigate the mold’s properties more closely.

The mold was later identified as Penicillium notatum, and Fleming’s accidental discovery became the foundation for antibiotic medicine. Penicillin has since saved countless lives and remains one of the most important medical breakthroughs in human history. Without Fleming’s curiosity about a “ruined” experiment, modern medicine might look very different.

The Radioactive Accident That Revealed Invisible Rays

In 1896, Henri Becquerel was studying phosphorescence in uranium salts, expecting to prove that sunlight was necessary for uranium to emit radiation. He had prepared an experiment where uranium salts would be exposed to sunlight and then placed on photographic plates wrapped in black paper.

Unfortunately, Paris experienced several cloudy days, preventing Becquerel from conducting his planned experiment. He stored the uranium salts in a drawer along with the wrapped photographic plates, intending to wait for better weather. When he finally developed the plates days later, he was shocked to find clear impressions of the uranium salts.

This accidental discovery revealed that uranium emitted radiation continuously, without any external energy source. Becquerel had discovered radioactivity, a phenomenon that would later lead to revolutionary developments in nuclear physics, medical imaging, and cancer treatment. His cloudy weather mishap opened an entirely new field of science.

A Sticky Situation That Stuck Around

In 1968, Spencer Silver was working at 3M, attempting to create a super-strong adhesive for aerospace applications. Instead, he accidentally created a weak, pressure-sensitive adhesive that could be easily removed without leaving residue. His colleagues initially considered the invention a failure because it didn’t meet the project’s requirements.

For years, Silver promoted his “failed” adhesive within 3M, believing it had potential applications. In 1974, his colleague Art Fry was singing in his church choir and became frustrated with bookmarks falling out of his hymnal. He remembered Silver’s repositionable adhesive and used it to create bookmarks that would stick but not damage the pages.

This collaboration led to the development of Post-it Notes, which became one of 3M’s most successful products. The accidental weak adhesive that was initially considered a failure generated billions in revenue and revolutionized office organization worldwide.

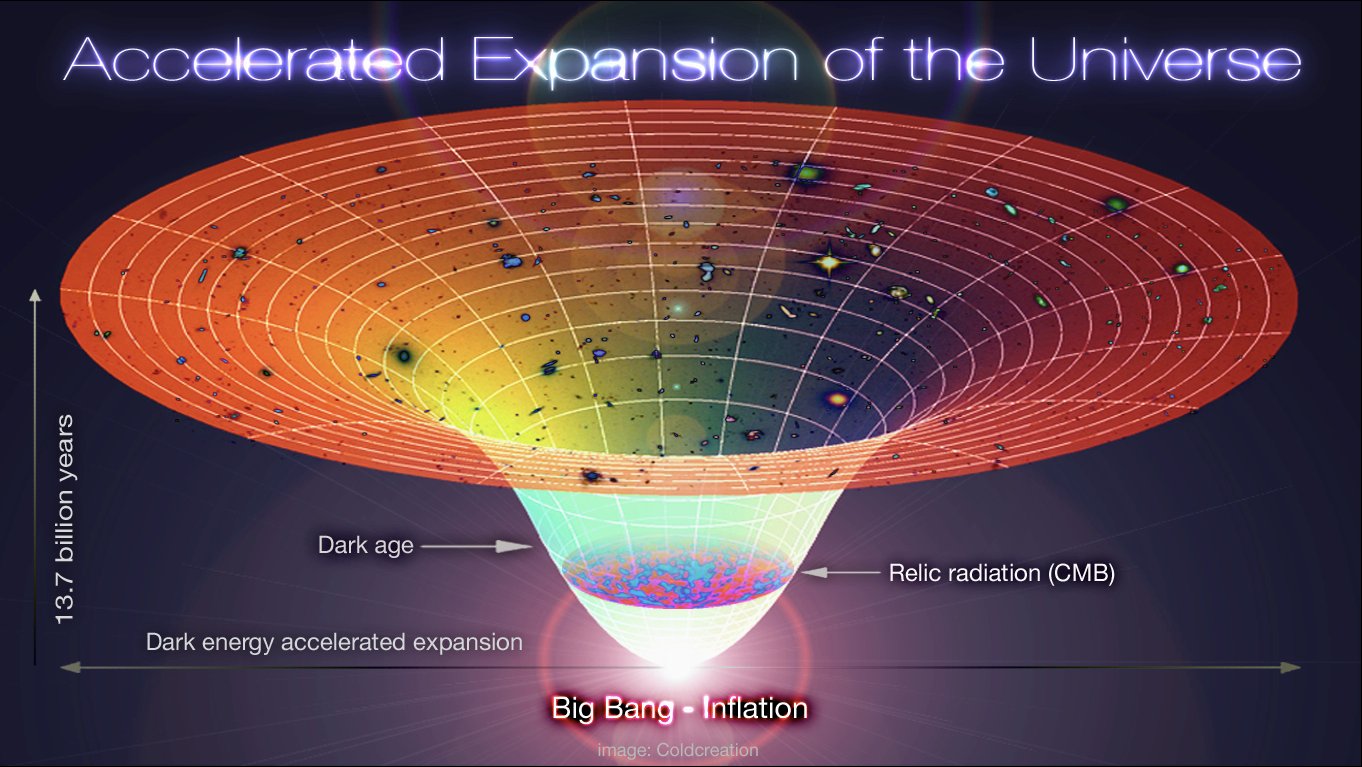

The Cosmic Background Radiation Discovery

In 1965, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were working with a large horn antenna at Bell Labs, attempting to detect radio waves from space. They were frustrated by persistent background noise that seemed to come from every direction in the sky. Initially, they thought the interference was caused by pigeon droppings in their antenna.

After cleaning the antenna thoroughly and even relocating the pigeons, the mysterious noise persisted. The two researchers spent months trying to eliminate what they considered an annoying technical problem. They measured the noise at different times of day and in different seasons, but it remained constant.

Eventually, they learned that Princeton physicists had predicted the existence of cosmic microwave background radiation left over from the Big Bang. Their “annoying noise” was actually the echo of the universe’s creation, providing crucial evidence for the Big Bang theory. This accidental discovery earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978.

The Explosive Discovery of Dynamite

Alfred Nobel was working on creating a safer way to handle nitroglycerin, a powerful but extremely unstable explosive. In 1866, while transporting nitroglycerin, one of his shipments accidentally leaked and soaked into diatomaceous earth packing material. Nobel initially thought the leak had ruined the explosive.

However, when he tested the nitroglycerin-soaked earth, he discovered it was much more stable than pure nitroglycerin while retaining its explosive power. This accidental combination created dynamite, which could be safely handled, transported, and used in construction and mining operations.

Nobel’s accidental discovery revolutionized construction, mining, and demolition industries. The wealth generated from dynamite later funded the Nobel Prizes, turning an accidental military explosive into a legacy that celebrates achievements in peace, science, and literature.

A Photographic Accident That Captured Time

In 1827, Nicéphore Niépce was experimenting with different chemicals to create permanent images. He was working with bitumen of Judea, a naturally occurring asphalt, coating it on pewter plates. During one experiment, he accidentally left a coated plate exposed to sunlight for an unusually long time – about eight hours.

When Niépce returned to his workshop, he found that the bitumen had hardened in areas exposed to light while remaining soft in shadowed areas. He could wash away the soft bitumen with lavender oil, leaving behind a permanent image. This accidental overexposure created the world’s first permanent photograph.

His mistake launched the entire field of photography, fundamentally changing how humans document and perceive the world. The accident that Niépce initially considered a failed experiment became the foundation for visual media, journalism, and artistic expression that continues to evolve today.

The Accidental Discovery of Safety Glass

In 1903, French chemist Édouard Bénédictus accidentally knocked a glass flask off his laboratory bench. He expected to find shattered glass scattered across the floor, but instead discovered that the flask had cracked but held together in one piece. The flask had previously contained cellulose nitrate, which had evaporated and left an invisible coating inside.

Intrigued by this unexpected result, Bénédictus began experimenting with different materials to create similar effects. He discovered that placing cellulose nitrate between two pieces of glass created a composite material that wouldn’t shatter into dangerous shards when broken.

This accidental discovery led to the development of laminated safety glass, which became essential for automobile windshields and architectural applications. Bénédictus’s clumsy moment in the lab has since prevented countless injuries and deaths from glass-related accidents in vehicles and buildings worldwide.

The Slippery Discovery of Teflon

In 1938, Roy Plunkett was working for DuPont, attempting to create a new refrigerant gas. He was experimenting with tetrafluoroethylene gas stored in pressurized cylinders. When he opened one cylinder expecting gas to flow out, nothing happened. Assuming the cylinder was empty, he cut it open to investigate.

Inside, Plunkett found a white, waxy substance that had somehow formed from the gas. This mysterious material was slippery, chemically inert, and had an extremely high melting point. He had accidentally created polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which would later be marketed as Teflon.

The accidental polymer became invaluable in aerospace applications, non-stick cookware, and countless industrial processes. Plunkett’s curiosity about an “empty” cylinder led to one of the most versatile materials in modern manufacturing, proving that even apparent failures can yield extraordinary results.

The Colorful Accident That Dyed the World

In 1856, eighteen-year-old William Henry Perkin was working in his home laboratory, attempting to synthesize quinine for malaria treatment. He was experimenting with coal tar derivatives when one of his reactions produced a black, tar-like substance instead of the expected clear solution. Most chemists would have discarded this apparent failure.

However, Perkin noticed that when he added alcohol to clean his equipment, the black residue dissolved into a beautiful purple solution. This accidental discovery created the first synthetic dye, which he named mauveine. The color was more vibrant and long-lasting than any natural dye available at the time.

Perkin’s accidental purple dye launched the synthetic dye industry and made him wealthy at a young age. His discovery democratized colored textiles, making vibrant clothing affordable for ordinary people and revolutionizing the fashion industry. The teenager’s “failed” experiment transformed how the world sees color.

The Accidental Birth of Stainless Steel

In 1913, Harry Brearley was working in Sheffield, England, attempting to develop steel that could resist erosion in gun barrels. He was experimenting with different steel alloys containing varying amounts of chromium. After numerous failed attempts, he discarded many of his experimental samples in a scrap heap outside his laboratory.

Weeks later, Brearley noticed that while other metal scraps had rusted, his chromium-steel samples remained bright and corrosion-free. This accidental observation led him to investigate the anti-corrosive properties of chromium-steel alloys more systematically.

His discovery of stainless steel revolutionized countless industries, from kitchen appliances to medical instruments to architectural construction. The discarded “failures” that caught his attention became the foundation for one of the most important metallurgical advances of the 20th century.

The Bouncing Discovery of Silly Putty

During World War II, James Wright was working for General Electric, attempting to create a synthetic rubber substitute to help the war effort. In 1943, he accidentally dropped boric acid into silicone oil during one of his experiments. The resulting substance bounced when dropped, stretched like taffy, and could pick up images from newspapers.

The military showed no interest in Wright’s accidental creation because it had no practical applications for the war effort. The strange substance sat unused in laboratories for years until toy store owner Ruth Fallgatter recognized its entertainment potential at a party in 1949.

Silly Putty became one of the most successful toys of the 20th century, entertaining millions of children worldwide. Wright’s “failed” rubber substitute proved that sometimes the most valuable discoveries come from experiments that don’t achieve their intended purpose.

The Sweet Accident of Aspartame

In 1965, James Schlatter was working for G.D. Searle Company, researching potential treatments for stomach ulcers. He was synthesizing aspartic acid derivatives when he accidentally spilled some of his experimental compound on his hand. Later, while licking his finger to pick up a piece of paper, he noticed an intensely sweet taste.

Schlatter realized that the sweetness was coming from the spilled chemical on his hand. He began testing the compound more systematically and discovered that it was approximately 200 times sweeter than sugar. This accidental discovery led to the development of aspartame, marketed as NutraSweet and Equal.

The accidental sweetener revolutionized the diet food industry and provided a sugar alternative for diabetics and weight-conscious consumers. Schlatter’s contaminated finger led to a multi-billion-dollar industry and changed how people approach low-calorie eating.

The Accidental Discovery of X-rays

In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen was experimenting with cathode rays in his laboratory at the University of Würzburg. He was working with a cathode ray tube covered in black cardboard when he noticed a mysterious glow coming from a nearby screen coated with barium platinocyanide. This glow persisted even when the tube was completely covered.

Röntgen realized that some unknown type of radiation was passing through the cardboard and causing the screen to fluoresce. He began systematically investigating these mysterious rays, which he called “X-rays” because their nature was unknown. He discovered that these rays could pass through human tissue but were absorbed by bones.

This accidental discovery revolutionized medical diagnosis and earned Röntgen the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901. X-rays became an essential tool in medicine, allowing doctors to see inside the human body without surgery. His chance observation of an unexpected glow transformed medical practice forever.

The Accidental Invention of the Pacemaker

In 1956, Wilson Greatbatch was working on a device to record heart sounds when he accidentally grabbed the wrong resistor from his parts box. He installed a 1-megohm resistor instead of the 10,000-ohm resistor his circuit required. When he tested the circuit, it produced rhythmic electrical pulses instead of the expected recording function.

Greatbatch immediately recognized that these regular pulses resembled the electrical signals that control heartbeats. He realized that his accidental circuit could potentially be used to regulate irregular heart rhythms. This sparked his interest in developing an implantable device to control heart function.

His accidental discovery led to the development of the first implantable pacemaker, which has since saved millions of lives worldwide. The wrong resistor that initially seemed like a simple mistake became the foundation for modern cardiac care and cardiac rhythm management.

These accidental discoveries demonstrate that scientific progress often comes from unexpected directions. The greatest breakthroughs frequently happen when researchers remain curious about anomalies rather than dismissing them as failures. From life-saving medications to revolutionary technologies, many of our most important scientific advances emerged from simple mistakes, contaminated samples, or equipment failures that caught the attention of observant scientists. The next time something doesn’t go according to plan, remember that you might be witnessing the birth of the next great discovery. What accidental breakthrough might be waiting in your own unexpected moments?