Imagine standing on a beach where the waves have fallen silent forever. No seagulls cry overhead, no crabs scuttle across the sand, and the water stretches endlessly without a single ripple of life. This nightmare scenario actually happened 252 million years ago during the Permian-Triassic extinction event, when our planet’s oceans became graveyards on an unimaginable scale. Scientists call it the Great Dying, and for good reason – it wiped out 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates, making it the most catastrophic mass extinction in Earth’s history.

When Life Nearly Ended

The Permian-Triassic boundary tells a story more terrifying than any disaster movie. Fossil records show that within just 60,000 years – a blink of an eye in geological terms – our planet transformed from a thriving biosphere into a barren wasteland. The extinction happened so rapidly that many creatures didn’t even have time to evolve survival strategies.

What makes this event particularly haunting is its completeness. Unlike other mass extinctions that affected specific groups of organisms, the Great Dying was an equal-opportunity destroyer. From microscopic plankton to massive marine reptiles, from delicate coral reefs to sturdy brachiopods, nothing was spared from nature’s most brutal purge.

The Siberian Traps: Earth’s Volcanic Apocalypse

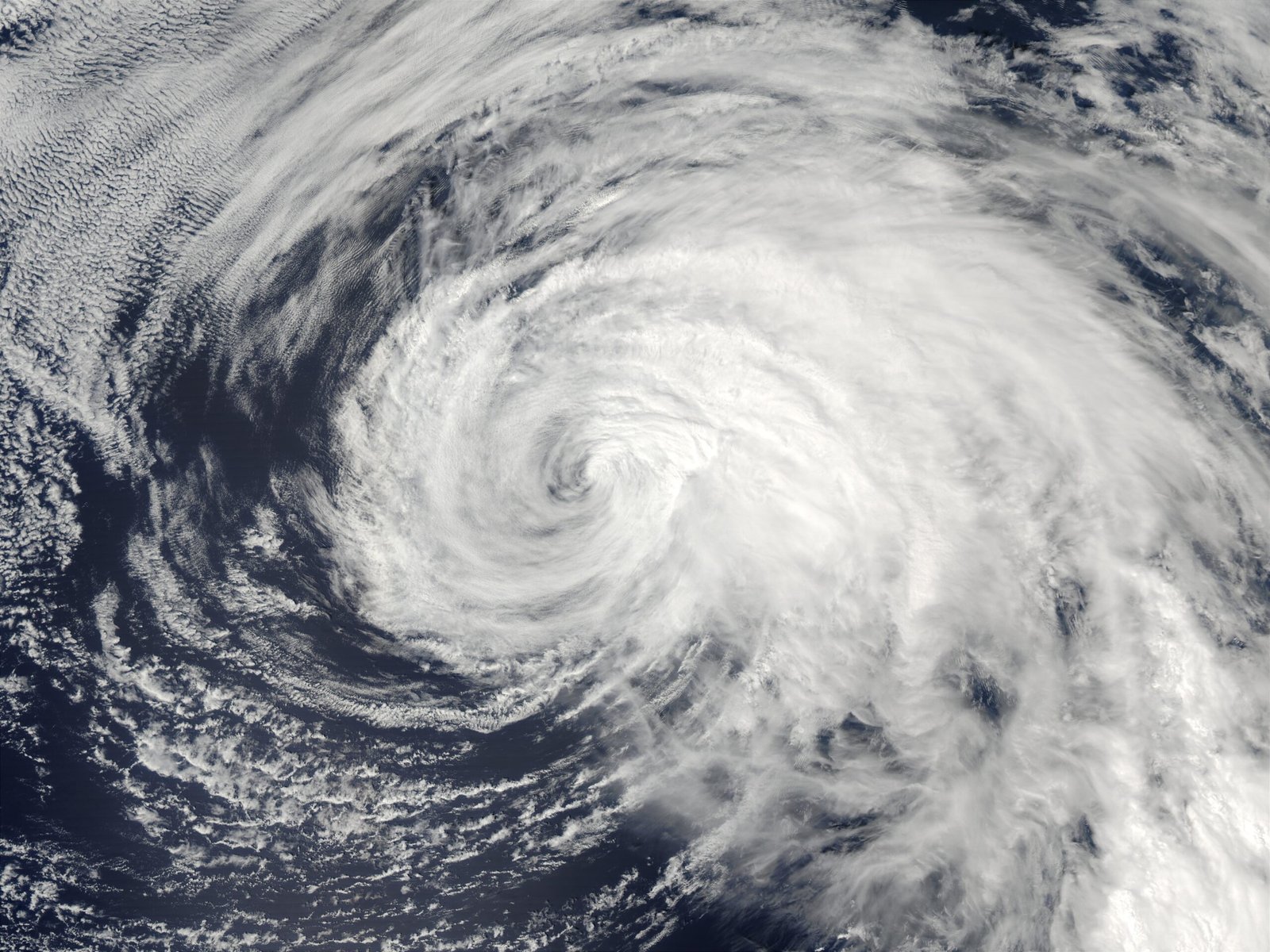

Picture volcanic eruptions so massive they could bury entire continents under molten rock. The Siberian Traps, covering an area larger than Western Europe, represent one of the largest volcanic events in Earth’s history. These weren’t gentle mountain eruptions – they were catastrophic outpourings of lava that continued for over a million years.

The scale defies comprehension. Scientists estimate that these eruptions released enough lava to cover the entire United States in a layer 300 feet thick. The volcanic activity didn’t just change the landscape; it poisoned the atmosphere with sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide, and other toxic gases that would prove lethal to life on a global scale.

Acid Rain That Lasted Millennia

The Siberian eruptions turned Earth’s atmosphere into a chemical weapon. Sulfur compounds spewed into the sky created acid rain so corrosive it could dissolve limestone and kill forests across continents. Fossil evidence shows that plant life suffered severe damage, with many species showing signs of acid burn on their preserved leaves.

This wasn’t a brief shower of acid rain – it was a sustained assault lasting thousands of years. The acidity levels were so extreme that they disrupted the entire food chain, starting with the microscopic organisms that formed the base of marine ecosystems. When these tiny creatures died, everything that depended on them followed suit.

The Great Suffocation: Oxygen Vanishes

Perhaps the most insidious killer was the gradual disappearance of oxygen from the oceans. As volcanic gases continued to pour into the atmosphere, they triggered a cascade of chemical reactions that stripped oxygen from seawater. Marine animals essentially suffocated in their own habitat, unable to extract the life-giving gas they needed to survive.

Fossil evidence reveals layers of black shale from this period, indicating oxygen-depleted conditions that persisted for millions of years. These dark sediments serve as tombstones for entire ecosystems, marking the spots where thriving marine communities once existed. The irony is heartbreaking – creatures that had ruled the seas for hundreds of millions of years were defeated by the very element they depended on simply vanishing.

Temperature Shock: When Earth Became Venus

The volcanic activity triggered a greenhouse effect that would make today’s climate change look mild by comparison. Global temperatures soared by 10-15 degrees Celsius, turning Earth into a furnace that few organisms could survive. The polar ice caps melted completely, raising sea levels and flooding coastal habitats where many species lived.

Fossil plants from this period show adaptations typical of extreme heat stress – thick waxy coatings and reduced leaf surfaces. But even these desperate evolutionary responses weren’t enough to save most species from the relentless heat. The planet had become too hot for life as it existed, forcing a complete reorganization of Earth’s biological systems.

The Reef Builders’ Final Stand

Coral reefs, those underwater cities of biodiversity, faced complete annihilation during the Great Dying. The combination of acidification, rising temperatures, and oxygen depletion created conditions that no coral could survive. Fossil reefs from the late Permian show clear signs of stress – bleached skeletons and stunted growth patterns that tell a story of desperate struggle.

What’s particularly tragic is that these reef ecosystems had taken millions of years to develop their complex interdependencies. Thousands of species relied on coral reefs for shelter, food, and breeding grounds. When the reefs died, they took entire underwater civilizations with them, leaving behind only limestone graveyards that paleontologists study today.

Trilobites: The End of an Era

The Great Dying marked the final chapter for trilobites, those armored arthropods that had ruled the seas for over 250 million years. These incredibly successful creatures had survived multiple previous extinctions, adapting to changing conditions with remarkable resilience. But the Permian-Triassic extinction proved too much even for these ultimate survivors.

Trilobite fossils from the late Permian show increasingly smaller sizes and simplified structures, suggesting populations under severe stress. The last known trilobite species clung to existence in the deepest parts of the ocean, but even these final refuges couldn’t protect them from the global catastrophe. Their extinction marked the end of one of evolution’s greatest success stories.

The Brachiopod Massacre

Brachiopods, those shell-bearing filter feeders that once dominated shallow seas, suffered a catastrophic collapse during the Great Dying. These creatures had been marine superstars for hundreds of millions of years, but their filter-feeding lifestyle made them particularly vulnerable to the toxic conditions that developed in Permian oceans.

Fossil beds from this period contain layers upon layers of brachiopod shells – evidence of mass die-offs that happened repeatedly as conditions worsened. The few species that survived were relegated to deep-water environments, never again achieving the dominance they had enjoyed throughout the Paleozoic era. Their decline paved the way for mollusks to take over shallow marine environments.

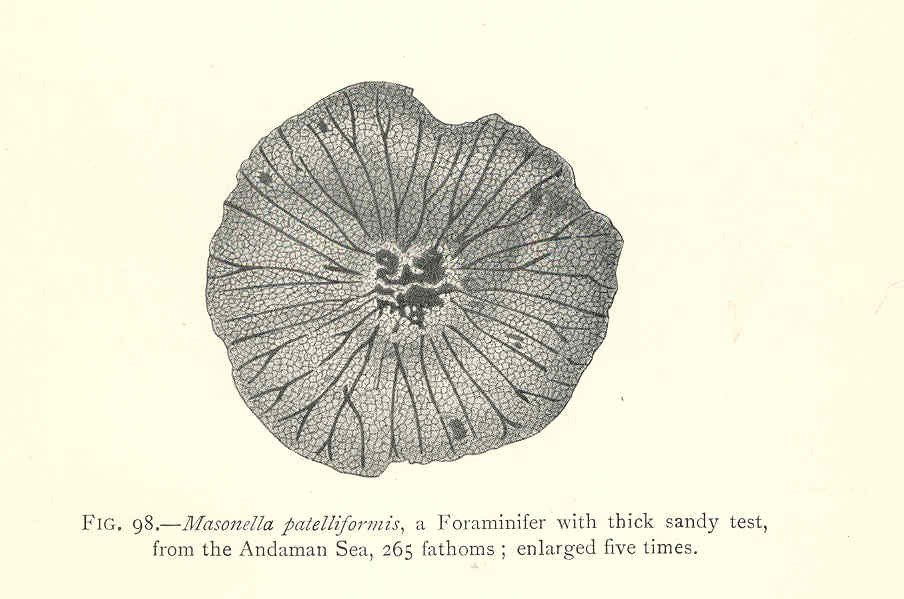

Microscopic Mayhem: When the Food Web Collapsed

The extinction’s most devastating impact might have been on microscopic marine life – the invisible foundation of ocean ecosystems. Foraminifera, tiny shell-bearing organisms that float in the water column, suffered near-total extinction. These microscopic creatures were the primary food source for countless larger organisms, and their disappearance triggered a domino effect throughout the marine food web.

Scientists studying sediment cores from this period find dramatic changes in the fossil record of these tiny organisms. Where once there were dozens of species in each sample, post-extinction samples contain only a few hardy survivors. This microscopic apocalypse effectively reset marine ecosystems, forcing evolution to start over from scratch.

The Fungal Takeover

In the aftermath of the Great Dying, something unexpected happened – fungi inherited the Earth. With most plants and animals dead or dying, decomposing organic matter accumulated in massive quantities. Fungi, those masters of decay, thrived in this post-apocalyptic world, creating what scientists call a “fungal spike” in the fossil record.

This fungal boom lasted for thousands of years, as these organisms slowly broke down the remains of Earth’s former biosphere. In some locations, fungal spores make up over 90% of the fossil remains from this period. It’s a haunting reminder that even in Earth’s darkest hour, life found a way to persist, even if it was just the life that feeds on death.

Land Animals’ Desperate Struggle

While marine life faced the worst of the extinction, land animals didn’t escape unscathed. The fossil record shows that many groups of terrestrial vertebrates suffered severe population crashes. Synapsids, the ancestors of mammals, were hit particularly hard, with many lineages disappearing entirely.

The few fossils that remain from this period tell stories of animals pushed to the brink of existence. Reduced body sizes, simplified bone structures, and evidence of nutritional stress suggest that terrestrial ecosystems were on the verge of complete collapse. Only the most adaptable and resilient species managed to survive this terrestrial nightmare.

The Survivors’ Secret

What separated the survivors from the victims? Scientists have discovered that the organisms that made it through the Great Dying shared certain characteristics – they were typically small, had simple body plans, and could tolerate extreme environmental conditions. These “disaster taxa” weren’t necessarily the most successful groups before the extinction, but they had the right combination of traits to survive the apocalypse.

Many survivors were what scientists call “generalists” – organisms that could eat a variety of foods and live in different environments. Specialists, no matter how perfectly adapted to their particular niche, were doomed when their specific environmental needs could no longer be met. The extinction was evolution’s ultimate test of adaptability.

Chemical Fingerprints of Doom

Modern technology allows scientists to read the chemical signatures left behind by the Great Dying. Isotope ratios in ancient rocks reveal details about atmospheric composition, ocean chemistry, and even the pace of extinction. These chemical fingerprints paint a picture of environmental conditions so extreme they challenge our understanding of what life can endure.

Carbon isotope ratios show massive disruptions to the global carbon cycle, while sulfur isotopes reveal the scale of volcanic emissions. Perhaps most telling are the ratios of different oxygen isotopes, which indicate the severe temperature fluctuations that characterized this period. These chemical clues provide a scientific foundation for understanding just how close Earth came to becoming permanently lifeless.

The Long Road to Recovery

The Great Dying didn’t end with a whimper – it was followed by millions of years of ecological instability. The fossil record shows that it took approximately 10 million years for biodiversity to begin recovering, and even longer for complex ecosystems to re-establish themselves. This recovery period was marked by repeated setbacks and false starts as life struggled to gain a foothold in the transformed world.

The ecosystems that eventually emerged were fundamentally different from those that existed before the extinction. New groups of organisms rose to prominence, filling ecological niches left vacant by the extinction. This pattern of destruction and renewal represents one of evolution’s most dramatic reinventions, setting the stage for the rise of dinosaurs and eventually mammals.

Modern Parallels: Are We Repeating History?

The fossil evidence from the Great Dying offers sobering parallels to our current environmental crisis. Rising temperatures, ocean acidification, and mass species extinctions are all happening today, driven by human activities rather than volcanic eruptions. The rate of change we’re experiencing now is comparable to what happened 252 million years ago, raising uncomfortable questions about our planet’s future.

Scientists studying the Permian-Triassic extinction have identified warning signs that preceded the catastrophe – many of which are visible in our modern world. The lesson from the fossil record is clear: when environmental changes happen too quickly, even the most successful species can disappear overnight. The Great Dying serves as both a window into Earth’s past and a warning about its future.

Lessons from the Abyss

The Great Dying teaches us that life on Earth is far more fragile than we might imagine. Despite billions of years of evolution and the development of countless survival strategies, 96% of marine species couldn’t adapt quickly enough to survive the changing conditions. This sobering reality reminds us that no species, no matter how successful, is guaranteed survival in the face of rapid environmental change.

Yet the story also reveals life’s incredible resilience. From the ashes of the worst extinction in Earth’s history, new forms of life emerged and eventually flourished. The survivors didn’t just persist – they diversified and adapted, creating the foundation for all modern ecosystems. This duality of fragility and resilience defines life’s relationship with our ever-changing planet.

The fossil clues from Earth’s worst mass extinction paint a picture of a planet pushed beyond its limits, where the very foundations of life crumbled in the face of environmental catastrophe. The Great Dying wasn’t just another extinction event – it was a complete reset of life on Earth, forcing evolution to begin again from the scattered survivors of a global apocalypse. As we face our own environmental challenges today, the lessons buried in 252-million-year-old rocks have never been more relevant. The question remains: will we learn from Earth’s darkest chapter, or are we destined to repeat it?