Picture this: you’re walking along a beautiful beach, the salty breeze carrying the sound of crashing waves. Suddenly, you spot a plastic bag dancing in the wind before it tumbles into the ocean. What happens next might shock you. That simple plastic bag you just witnessed entering the water could potentially travel thousands of miles, crossing entire ocean basins and washing up on shores you’ve never even heard of. The ocean’s invisible highways are more powerful and far-reaching than most people realize, and they’re carrying our trash to places we never imagined.

The Ocean’s Hidden Highway System

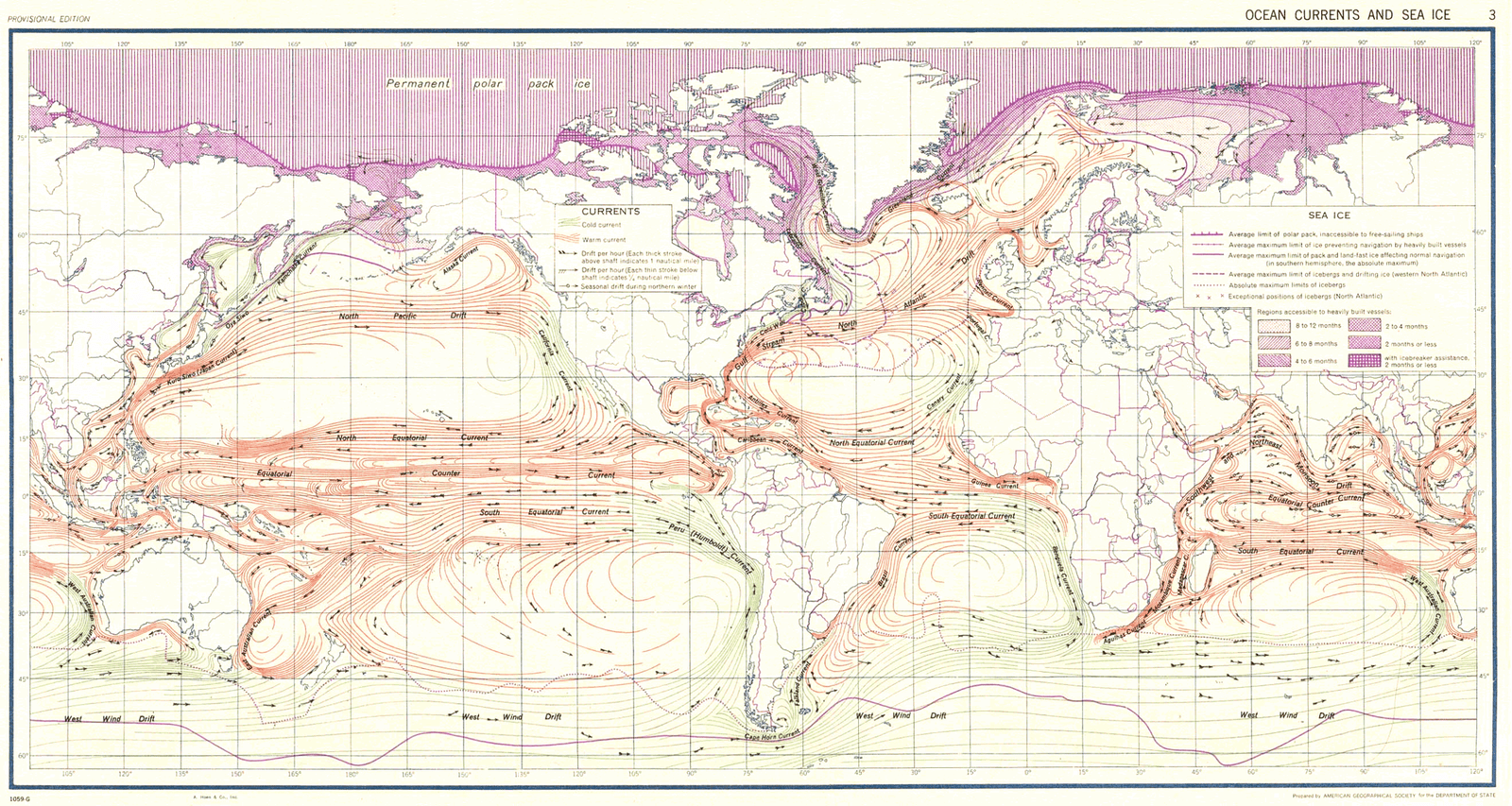

Ocean currents act like massive conveyor belts, moving water and everything in it across vast distances. These underwater rivers are driven by a complex combination of wind patterns, temperature differences, and the Earth’s rotation. The Gulf Stream alone moves water at speeds of up to 5.6 miles per hour, carrying warm water from the Caribbean toward Europe.

What makes these currents particularly fascinating is their consistency and predictability. Scientists can map these underwater highways with remarkable accuracy, understanding how they connect different parts of our planet’s oceans. A plastic bag entering the water off the coast of North Carolina could theoretically ride the Gulf Stream all the way to the shores of Ireland or Norway.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch: A Floating Continent of Trash

The most infamous example of how far plastic can travel is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a swirling mass of debris twice the size of Texas. This accumulation zone sits between Hawaii and California, where converging currents create a natural collection point for floating trash. Plastic bags from Asia, North America, and even South America eventually find their way to this underwater graveyard.

What’s particularly disturbing is that this garbage patch isn’t just one solid island of trash. Instead, it’s a dispersed collection of microplastics and larger debris that stretches across an area larger than many countries. The plastic density in some areas reaches 50 pounds per square mile, creating an environmental disaster that continues to grow.

Wind Patterns: The Ocean’s Invisible Puppet Master

Trade winds and seasonal weather patterns play a crucial role in determining where plastic bags end up. These atmospheric forces don’t just push debris along the surface; they also influence the deeper current systems that carry trash across entire ocean basins. The monsoon seasons in Asia, for example, can dramatically alter the paths that plastic takes through the Pacific Ocean.

During storm seasons, wind speeds can exceed 100 miles per hour, accelerating the movement of floating debris. A plastic bag that might normally take months to cross an ocean basin could complete the journey in just weeks during particularly intense weather systems. This acceleration effect means that trash from recent storms can appear on distant shores much faster than expected.

The Coriolis Effect: Earth’s Spin Changes Everything

The Earth’s rotation creates the Coriolis effect, which causes moving objects to curve as they travel across the planet’s surface. In the Northern Hemisphere, this effect causes ocean currents to curve to the right, while in the Southern Hemisphere, they curve to the left. This phenomenon is crucial for understanding how plastic bags navigate the ocean’s highway system.

Without the Coriolis effect, ocean currents would flow in straight lines from high-pressure to low-pressure areas. Instead, they create the circular patterns called gyres that dominate each ocean basin. These gyres act like giant whirlpools, trapping plastic debris in their centers and creating the garbage patches that have become environmental landmarks.

Temperature Differences: The Engine of Ocean Movement

Thermohaline circulation, often called the ocean’s “global conveyor belt,” is driven by differences in water temperature and salinity. Cold, dense water sinks at the poles and flows along the ocean floor toward the equator, while warm surface water moves toward the poles to replace it. This circulation pattern affects how plastic debris moves through different layers of the ocean.

A plastic bag might start its journey floating on the warm surface waters of the tropics, but changes in temperature and salinity can cause it to sink and join the deep-water currents. These deeper currents move much slower than surface currents, but they can carry plastic to entirely different ocean basins over periods of decades or even centuries.

The North Atlantic Drift: Europe’s Plastic Problem

The North Atlantic Drift is essentially the European extension of the Gulf Stream, and it’s responsible for carrying plastic debris from North America to European shores. This current system is why beaches in Ireland and Scotland regularly receive plastic bottles and bags with labels in English, despite being thousands of miles from their origin points.

Research has shown that plastic debris can travel from the Eastern United States to Western Europe in as little as 10 to 14 months. The journey isn’t direct; the plastic follows the curved path of the North Atlantic Gyre, but the end result is the same. European beachgoers are literally cleaning up America’s trash, and vice versa.

Seasonal Variations: When Ocean Highways Change Direction

Ocean currents aren’t static; they change with the seasons, altering the paths that plastic debris follows. The monsoon seasons in the Indian Ocean can completely reverse certain current patterns, sending plastic bags that were heading toward Africa suddenly traveling toward Australia instead. These seasonal shifts make it incredibly difficult to predict exactly where a specific piece of plastic will end up.

El Niño and La Niña events can also dramatically alter current patterns across the Pacific Ocean. During El Niño years, the normal flow of the Pacific currents weakens or even reverses, potentially sending plastic debris to entirely different destinations than it would reach during normal years. Climate change is making these variations more extreme and unpredictable.

The Journey of a Single Plastic Bag: A Case Study

Imagine a plastic bag entering the ocean off the coast of Los Angeles. Initially, it would likely join the California Current, which flows southward along the western coast of North America. This current could carry the bag as far south as Baja California, Mexico, covering roughly 1,000 miles in just a few months.

From there, the bag might encounter the North Equatorial Current, which flows westward across the Pacific Ocean. This current could transport the plastic bag across the entire Pacific basin, a journey of approximately 8,000 miles that could take 2-3 years to complete. Eventually, the bag might reach the Philippines, Japan, or even the coast of Asia.

Microplastics: When Bags Become Invisible Travelers

Not all plastic bags remain intact during their ocean journeys. UV radiation from the sun, salt water, and physical abrasion gradually break down plastic bags into smaller and smaller pieces called microplastics. These tiny fragments are virtually invisible to the naked eye but can travel even further than intact plastic bags.

Microplastics can become suspended in the water column and carried by deep-sea currents that intact plastic bags can’t access. They can also be ingested by marine animals and transported inside their bodies as the animals migrate. This biological transportation system can move plastic particles across ocean basins faster than any current system.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current: The Ocean’s Fastest Highway

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is the only current that flows completely around the globe, and it’s also the fastest-moving current system on Earth. This massive current carries 600 times more water than the Amazon River and can transport plastic debris around the entire Southern Hemisphere in just 8 years.

Plastic bags that enter this current system near South America, Africa, or Australia can potentially circumnavigate the globe multiple times. The current’s speed and consistency make it one of the most efficient ways for plastic debris to spread across the world’s oceans. Research has found plastic debris in pristine Antarctic waters that originated from populated areas thousands of miles away.

Beach Findings: Evidence of Global Plastic Travel

Beach cleanup volunteers around the world regularly find plastic bags with foreign labels, providing real-world evidence of how far plastic can travel. Beaches in Alaska have yielded plastic bags with Japanese text, while shores in Japan have collected bags with Korean and Chinese labels. These findings create a clear picture of the global nature of plastic pollution.

Some of the most surprising discoveries occur on remote islands in the middle of the ocean. Henderson Island in the South Pacific, despite being uninhabited and thousands of miles from the nearest population center, has one of the highest plastic debris densities in the world. The island sits in the path of the South Pacific Gyre, making it a collection point for plastic from multiple continents.

The Role of Density in Plastic Travel

Not all plastic behaves the same way in ocean currents. The density of different types of plastic determines whether they float on the surface or sink to deeper waters. Most plastic bags are made from low-density polyethylene, which is less dense than seawater and tends to float. This buoyancy keeps them in the fast-moving surface currents where they can travel the greatest distances.

However, when plastic bags become fouled with marine organisms or filled with sand and debris, their density can increase enough to cause them to sink. Once submerged, they enter the slower-moving deep-water currents and may eventually settle on the ocean floor. Recent deep-sea explorations have found plastic bags in ocean trenches more than 35,000 feet below the surface.

Gyres: The Ocean’s Plastic Collecting Systems

The world’s oceans contain five major gyres, each acting as a massive collection system for floating plastic debris. The North Pacific Gyre, home to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, is the largest and most studied, but similar accumulation zones exist in the North Atlantic, South Pacific, South Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.

These gyres create a natural trap for plastic debris, with currents flowing in circular patterns that gradually concentrate floating materials toward their centers. A plastic bag entering any of these gyre systems will eventually spiral toward the center, where it can remain trapped for decades. The residence time for plastic in these gyres can exceed 50 years.

Climate Change: Accelerating Plastic Distribution

Climate change is affecting ocean current patterns in ways that could accelerate the global distribution of plastic debris. Rising ocean temperatures are altering the strength and direction of major current systems, potentially creating new pathways for plastic to travel. The melting of polar ice caps is also adding fresh water to the oceans, which can disrupt the density-driven currents that move plastic through different ocean layers.

More frequent and intense storms are another factor that could accelerate plastic movement. Hurricane-force winds can push plastic debris much faster than normal current speeds, potentially cutting travel times across ocean basins in half. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events means that plastic debris is likely moving faster and farther than ever before.

The Mediterranean: A Plastic Bag’s Dead End

The Mediterranean Sea presents a unique case study in plastic bag travel because it’s essentially a closed system with limited connection to the world’s oceans. Plastic bags entering the Mediterranean through rivers or coastal cities tend to stay within the basin, circulating through the sea’s internal current systems. This creates an extremely high concentration of plastic debris in a relatively small area.

The Mediterranean’s unique geography means that plastic bags can travel from Spain to Turkey, or from Italy to North Africa, but they rarely escape to the Atlantic Ocean. This makes the Mediterranean one of the most plastic-polluted water bodies on Earth, with some areas containing plastic concentrations similar to those found in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

River Systems: The Plastic Highways to the Ocean

Most plastic bags don’t start their ocean journeys at the coast; they begin in rivers and streams that eventually connect to the sea. The world’s largest rivers, including the Amazon, Yangtze, and Mississippi, carry enormous quantities of plastic debris from inland areas to the ocean. These river systems act as conveyor belts, transporting plastic bags from cities and towns hundreds of miles inland directly to the ocean currents.

The speed at which plastic travels through river systems depends on the river’s flow rate and seasonal variations. During flood seasons, rivers can carry plastic debris to the ocean in just days or weeks. Once the plastic reaches the ocean, it immediately enters the current systems that will determine its ultimate destination.

The Future of Ocean Plastic: Predictive Modeling

Scientists are using sophisticated computer models to predict where plastic debris will travel in the future. These models take into account current patterns, wind systems, and seasonal variations to forecast the movement of plastic pollution. Some models can predict with remarkable accuracy where a piece of plastic will end up years or even decades after it enters the ocean.

These predictive models are becoming increasingly important for planning cleanup efforts and understanding the global scale of plastic pollution. By knowing where plastic is likely to accumulate, conservation organizations can focus their efforts on the most effective locations and times. The models also help scientists understand how changes in climate and ocean patterns might affect plastic distribution in the future.

Breaking the Cycle: Solutions and Hope

Understanding how far plastic bags can travel has led to innovative solutions for reducing ocean plastic pollution. Beach cleanup efforts are being coordinated internationally, with volunteers in one country cleaning up plastic that originated in another. This global approach recognizes that ocean plastic pollution is truly a worldwide problem that requires international cooperation.

New technologies are being developed to intercept plastic before it reaches the ocean current systems. River trash collection systems and coastal barriers can capture plastic debris before it begins its journey across the ocean basins. These interventions are most effective when placed at strategic locations where plastic enters the major current systems.

The journey of a single plastic bag through the ocean’s current systems reveals the interconnected nature of our planet’s waters. What starts as a piece of litter in one location can become an environmental problem thousands of miles away, affecting marine ecosystems and coastal communities that had no role in creating the pollution. The ocean’s currents don’t recognize national boundaries, making plastic pollution a truly global challenge that requires global solutions. Every plastic bag that enters the ocean becomes part of a vast, interconnected system that can transport our waste to the most remote corners of the planet. How many plastic bags from your local area do you think are currently traveling the ocean’s highways right now?