The story of the “Pharaoh’s Curse” haunted archaeologists for hundreds of years. It started with the excavation of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 and continued with the mysterious deaths of teams in Poland’s Casimir IV crypt in the 1970s. Scientists have now found a shocking twist: the fungus that was thought to be responsible for these deaths, Aspergillus flavus, may hold the key to a new way to treat cancer. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania turned this poisonous tomb dweller into a powerful drug that fights leukaemia in a groundbreaking study published in Nature Chemical Biology. This shows that nature can turn historical villains into medical heroes.

From Pharaoh’s Curse to Medical Marvel: The Fungus Behind the Legends

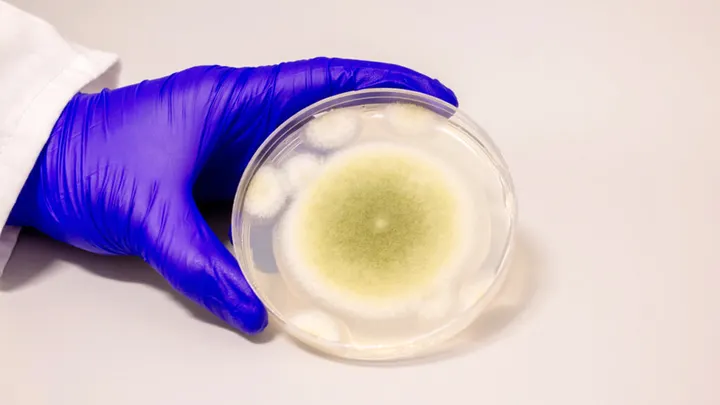

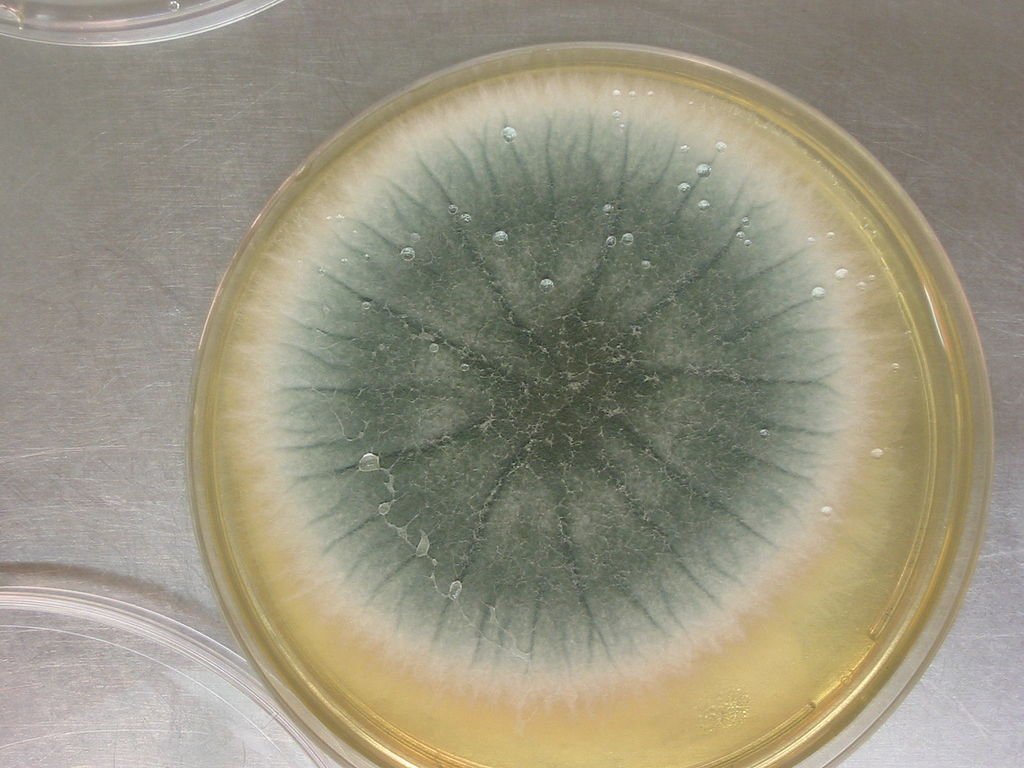

People don’t like Aspergillus flavus because it may live in sealed tombs for thousands of years and produce lethal spores when disturbed. After the Tutankhamun digs in the 1920s, doctors concluded that fungal spores were to blame for the severe lung illnesses that killed archaeologists. In the 1970s, this notion gained strength when 10 of the 12 researchers who entered King Casimir IV’s tomb perished. There, they later found A. flavus. The fungus develops best in decaying organic materials and isn’t extremely toxic to healthy individuals, but it can be lethal to persons with weak immune systems. It can make your lungs, brain, and heart sick.

The Discovery of Asperigimycins: A Rare Fungal Weapon Against Cancer

The Penn team found a rare type of molecule in A. flavus called RiPPs (ribosomally synthesised and post-translationally modified peptides). These chemicals are very common in bacteria but very rare in fungi because they were wrongly classified in the past. Qiuyue Nie, the lead researcher, said, “The synthesis of these compounds is complicated, but that complexity gives them remarkable bioactivity.” Two of the four RiPP variants found had the same effect on leukaemia cells as the FDA-approved drugs cytarabine and daunorubicin. A third variant, which was enhanced with a lipid from royal jelly, had the same effect.

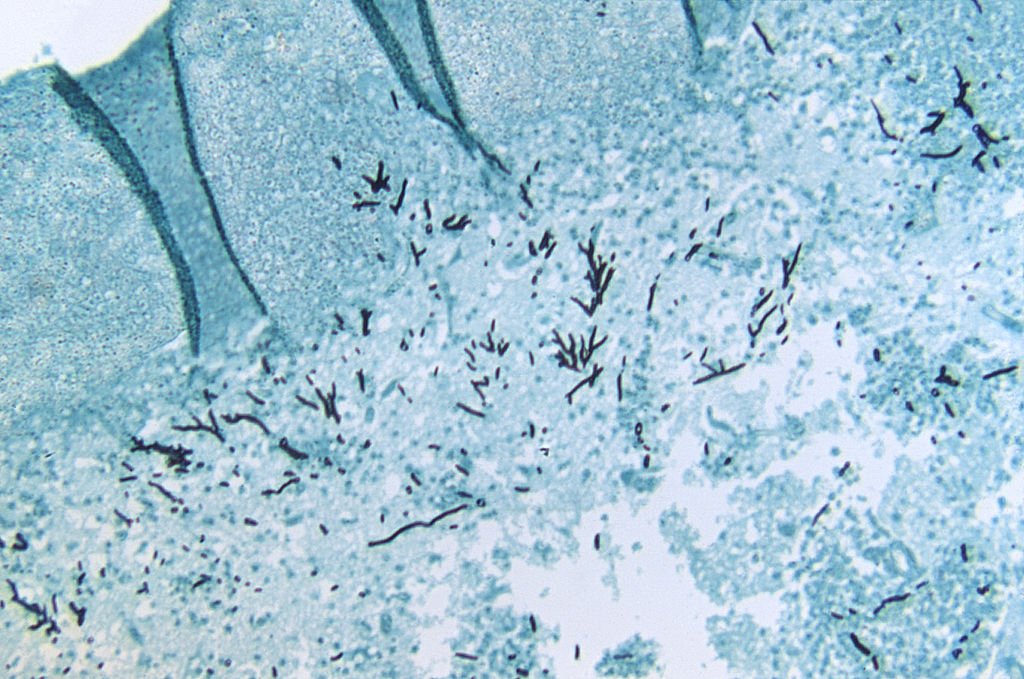

Cracking the Cellular Gateway: How the Drug Targets Cancer

The gene SLC46A3 is very important for the therapy to work because it lets asperigimycins get into leukaemia cells. This gene helps drugs get out of lysosomes, which are cellular compartments that often hold onto foreign substances. “It doesn’t just help asperigimycins get into cells; it might help other cyclic peptides do the same,” Nie said, pointing out that this could have bigger effects on drug delivery problems. Unlike regular chemotherapy, these drugs only stop leukaemia cells from forming microtubules, which stops them from dividing without hurting healthy tissues or other types of cancer, like breast or liver cancer.

Historical Irony: How a Killer Fungus Could Save Lives

The study shows a deep irony: a microbe that used to be connected to death now has the potential to save lives. “Fungi gave us penicillin,” said Sherry Gao, the senior author. “These results show that there are still many more medicines that come from natural sources that need to be found.” The team named the new molecules “asperigimycins” after the fungus that hosts them. This was a way to honour the fungus’s dark past while also celebrating its potential in medicine.

The Road Ahead: From Lab to Clinic

The results from the lab are promising, but a lot of testing needs to be done before human trials can begin. The team wants to test asperigimycins on animals first, and then move on to clinical trials. Genomic scans also show that other fungi may have similar RiPP-producing clusters, which suggests that there is a huge, untapped store of bioactive compounds. “Nature has given us this amazing pharmacy,” Gao said. “We have to find out its secrets.”

Conclusion: A New Chapter in the Story of Ancient Tombs

The story of Aspergillus flavus has changed from a curse to a cure, combining archaeology, history, and cutting-edge science. As scientists figure out more of nature’s secret medicines, the tombs that were once thought to be cursed may hold the keys to some of modern medicine’s most important discoveries.

Sources:

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.