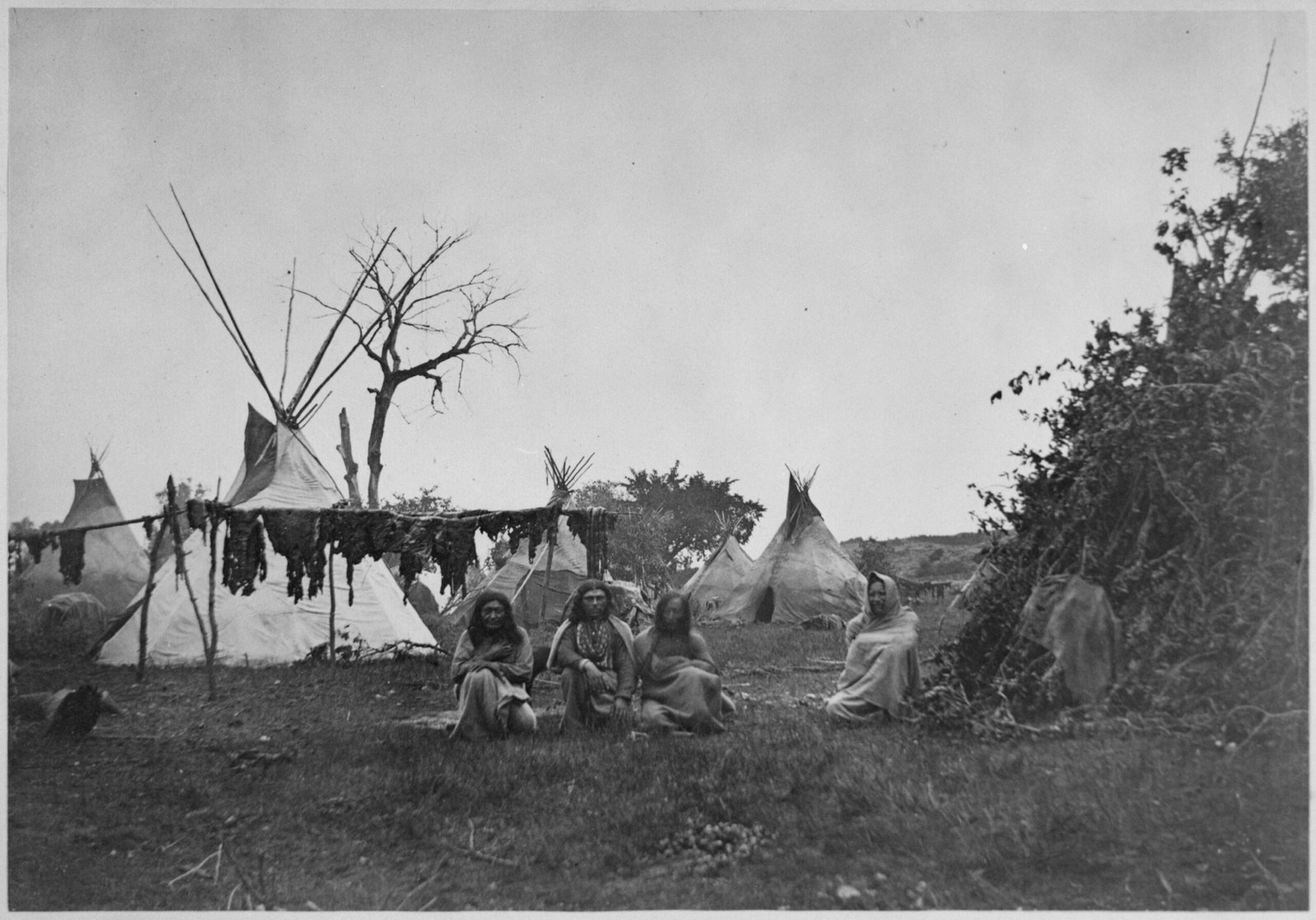

Imagine standing at the edge of a towering cliff, watching thousands of bison thunder across the plains below. Their hooves create a rumbling that shakes the earth beneath your feet. For over 6,000 years, this exact scenario played out at one of North America’s most ingenious hunting sites. The indigenous peoples of the Great Plains transformed a simple geological feature into a sophisticated hunting machine that sustained entire communities for millennia.

The Ancient Engineering Marvel That Changed Everything

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump represents one of humanity’s most remarkable examples of landscape engineering. This sandstone cliff in southern Alberta rises 35 feet above the surrounding prairie, creating the perfect natural trap for massive bison herds. The indigenous hunters didn’t just stumble upon this location – they carefully selected it after generations of observing bison behavior and migration patterns.

The cliff’s unique formation provided exactly what the hunters needed: a steep drop that would instantly kill or disable the massive animals. But the real genius lay in the extensive drive lanes that stretched for miles across the prairie. These carefully constructed pathways, marked by stone cairns and brush piles, guided the bison toward their fate with surgical precision.

Decoding the Mysterious Name’s Dark Origins

The site’s haunting name carries a chilling legend that speaks to the dangers of this ancient hunting ground. According to Blackfoot oral tradition, a young warrior wanted to witness the buffalo jump from below the cliff. He positioned himself under a rocky ledge to watch the spectacle unfold above him. When the massive herd came thundering over the edge, the sheer volume of falling animals crushed him beneath their weight.

His people found his body with his skull completely shattered, leading them to name the place “Estipah-skikikini-kots” – literally meaning “where he got his head smashed in.” This grim tale serves as both a warning and a testament to the overwhelming power of the buffalo jump technique.

The Sophisticated Science Behind Buffalo Psychology

The success of Head-Smashed-In relied on an incredibly deep understanding of bison behavior and psychology. These massive animals, weighing up to 2,000 pounds each, possessed surprising intelligence and strong herd instincts. The indigenous hunters spent generations studying their movements, learning that bison would follow familiar trails and respond predictably to certain stimuli.

During the rutting season, bulls became more aggressive and territorial, making them easier to manipulate. The hunters discovered that bison running in large groups would rarely break away from the herd, even when sensing danger ahead. This knowledge became the foundation for their elaborate hunting strategy.

The timing had to be absolutely perfect. Hunters would wait for optimal weather conditions – usually calm, clear days when the wind direction wouldn’t alert the animals to human presence. They also coordinated their efforts with the natural migration patterns that brought massive herds through the area each year.

The Elaborate Network of Stone Monuments

Stretching across the prairie for over 10 miles, an intricate system of stone cairns and drive lanes channeled bison toward the cliff. These weren’t random piles of rocks – each cairn was strategically placed to create a funnel effect. The drive lanes started wide on the prairie, sometimes spanning several miles, then gradually narrowed as they approached the cliff edge.

Archaeological evidence reveals that some of these stone markers stood over six feet tall, designed to appear threatening to the approaching bison. The hunters would hide behind these cairns, waving robes and making noise to keep the animals moving in the right direction. The entire system required coordination between dozens of hunters, each playing a specific role in the grand strategy.

The Runners: Masters of Endurance and Deception

The most dangerous job belonged to the buffalo runners – elite athletes who would initiate the hunt by getting close enough to the herd to start the stampede. These individuals possessed extraordinary speed, stamina, and courage. They would often disguise themselves in wolf skins or buffalo calf hides to get within striking distance of the massive animals.

Once the runner started the stampede, there was no turning back. The bison would charge forward at speeds up to 35 miles per hour, and the runner had to maintain his position at the front of the herd. One mistake could mean being trampled by thousands of hooves. The runner’s job was to lead the animals into the drive lanes and then dive to safety at the last possible moment.

These runners underwent years of training and held positions of tremendous respect within their communities. Their success or failure could mean the difference between a winter of plenty or starvation for hundreds of people.

Archaeological Treasures Buried in Time

The bone bed at Head-Smashed-In extends 36 feet deep in some areas, representing thousands of years of successful hunts. This massive accumulation of bison remains provides archaeologists with an unprecedented window into prehistoric life on the Great Plains. Each layer tells a story of climate change, human innovation, and survival strategies.

Excavations have uncovered over 100,000 stone tools, including incredibly sophisticated projectile points, knives, and scrapers. The craftsmanship of these tools rivals anything produced by modern artisans. Many of the stone materials came from quarries hundreds of miles away, indicating extensive trade networks.

The site also contains evidence of the complete utilization of every part of the buffalo. Bone needles, hide scrapers, and cooking implements show how nothing was wasted. This archaeological record demonstrates a level of resource management and sustainability that modern societies are still trying to achieve.

The Complete Utilization Philosophy

The indigenous peoples of the Great Plains developed a philosophy of complete utilization that would make modern environmentalists weep with envy. Every single part of the buffalo served a purpose, from the massive bones to the smallest sinew. The meat provided protein for immediate consumption and was processed into pemmican for long-term storage.

The hides became shelter, clothing, and storage containers. Bones were carved into tools, weapons, and ceremonial objects. Even the buffalo’s stomach lining was used as water containers. The horns became cups and spoons, while the sinew provided thread for sewing.

This approach to resource utilization wasn’t just practical – it was deeply spiritual. The hunters believed that wasting any part of the animal would offend the spirits and bring bad luck to future hunts. This philosophy sustained both the human communities and the buffalo populations for thousands of years.

Seasonal Rhythms and Hunting Cycles

The buffalo jump operated on a carefully orchestrated seasonal schedule that aligned with both human needs and bison migration patterns. The most productive hunts typically occurred in late fall, when the animals had fattened up for winter and their hides were at their thickest. This timing provided the maximum amount of meat and the highest quality materials for winter survival.

Spring hunts were less common but sometimes necessary after harsh winters. The hunters had to be more selective during these times, as the bison were often thinner and the hides were shedding. Summer hunts were rare because the animals were scattered across the vast prairie and more difficult to coordinate into large groups.

The hunting schedule also had to account for the needs of the community. Processing thousands of pounds of meat required enormous amounts of labor and time. The entire community would mobilize for these events, with specific roles assigned to men, women, children, and elders.

Sacred Ceremonies and Spiritual Connections

The buffalo jump wasn’t just a hunting technique – it was a sacred ceremony that connected the people to the land and the animals that sustained them. Before each hunt, elaborate rituals were performed to ensure success and to honor the spirits of the buffalo. Medicine men would conduct ceremonies to call the animals and to ask for their sacrifice.

The hunters believed that the buffalo gave themselves willingly to provide for human needs. This spiritual connection created a sense of responsibility and respect that governed every aspect of the hunt. Certain parts of the animal were reserved for ceremonial purposes, and specific protocols had to be followed during the processing.

These spiritual practices weren’t just superstition – they served important psychological and social functions. The ceremonies helped build community cohesion and provided a framework for managing the enormous responsibilities of the hunt. They also reinforced the values of respect, gratitude, and stewardship that kept the system sustainable.

Engineering Genius in Landscape Modification

The indigenous engineers who designed Head-Smashed-In demonstrated a level of landscape modification that rivals modern civil engineering projects. The drive lanes required moving thousands of tons of stone across miles of prairie. The cairns had to be positioned with mathematical precision to create the proper angles for guiding the bison.

The hunters also modified the cliff itself, creating specific jump points that would maximize the effectiveness of the drop. They built up certain areas with stone to create the optimal height and angle. They even constructed gathering basins at the bottom of the cliff to contain the animals and make processing more efficient.

This engineering work continued for generations, with each group adding improvements and refinements. The site represents one of the longest continuously operated engineering projects in human history, spanning over 6,000 years of constant use and modification.

Climate Change and Adaptation Strategies

The archaeological record at Head-Smashed-In reveals how the indigenous peoples adapted their hunting strategies to changing climate conditions over millennia. During warmer periods, when the prairie was drier, the bison herds were smaller and more scattered. The hunters adjusted their techniques accordingly, focusing on smaller, more targeted jumps.

During colder periods, massive herds would concentrate in sheltered areas, creating opportunities for larger hunts. The hunters developed different strategies for different climate conditions, showing remarkable flexibility and adaptability. They also learned to read long-term weather patterns and plan their hunts accordingly.

This adaptation wasn’t just reactive – it was proactive. The hunters would modify their drive lanes and cairn systems based on changing migration patterns and animal behavior. This constant evolution and adaptation allowed the site to remain productive for thousands of years despite significant environmental changes.

The Social Organization Behind Success

The success of Head-Smashed-In required an incredibly sophisticated level of social organization and cooperation. A typical hunt involved hundreds of people working in perfect coordination. The planning alone could take weeks, with scouts tracking the herds and weather watchers monitoring conditions.

Each person had a specific role and responsibility. The runners initiated the stampede, the drivers guided the animals through the lanes, the processors handled the meat and hides, and the spiritual leaders conducted the ceremonies. Children and elders also had important roles, from gathering firewood to teaching traditional knowledge.

The distribution of the meat and materials followed strict protocols that ensured everyone received their fair share. The hunters who took the greatest risks often received the choicest cuts, but the system also provided for widows, orphans, and those unable to participate in the hunt. This social safety net was crucial for community survival.

Trade Networks and Economic Impact

Head-Smashed-In wasn’t just a local hunting site – it was a major economic center that connected trade networks across the continent. The abundance of buffalo products created surplus wealth that could be traded for goods from as far away as the Pacific Coast and the Great Lakes region. Shell ornaments, copper tools, and obsidian blades found at the site indicate extensive trade relationships.

The site also served as a meeting place for different indigenous groups. During the hunting season, multiple bands would gather to participate in the communal hunts. These gatherings provided opportunities for trade, intermarriage, and the exchange of information and technology.

The economic impact extended far beyond the immediate participants. The buffalo products from Head-Smashed-In supported communities throughout the region, creating a network of interdependence that strengthened the entire social fabric of the Great Plains.

Revolutionary Food Preservation Techniques

The massive amount of meat produced at Head-Smashed-In required innovative food preservation techniques that could keep the protein fresh for months. The indigenous peoples developed pemmican, a concentrated food that combined dried meat, fat, and berries into a nutrient-dense package that could last for years.

The processing techniques were incredibly sophisticated. The meat was cut into thin strips and dried on wooden racks, while the fat was rendered and mixed with the dried meat and berries. The final product was so nutritious and long-lasting that it became the standard food for long-distance travel and winter survival.

The site also shows evidence of other preservation techniques, including smoking, freezing in natural ice cellars, and fermentation. These methods allowed the communities to store enough food to survive harsh winters and to trade surplus with other groups. The food preservation technology developed at Head-Smashed-In was so effective that it was adopted by European explorers and fur traders.

The Decline and Transformation

The traditional buffalo jump system at Head-Smashed-In began to decline in the 1700s as horses were introduced to the Great Plains. The horse revolutionized buffalo hunting, making it possible to hunt individual animals rather than entire herds. This new technology was more efficient for smaller groups but couldn’t match the massive productivity of the communal jumps.

The arrival of European diseases and the expansion of the fur trade also disrupted the traditional social systems that made the buffalo jumps possible. The large gatherings required for successful jumps became dangerous as diseases spread rapidly through the concentrated populations.

The final blow came with the near-extinction of the buffalo in the late 1800s. The massive herds that had sustained the jump sites for thousands of years were reduced to a few hundred animals, making the traditional hunting methods impossible. The last documented use of Head-Smashed-In as a hunting site occurred in the 1870s.

Modern Conservation and UNESCO Recognition

In 1981, Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump became a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognizing its outstanding universal value to humanity. The site is now protected and managed as a cultural landscape that preserves both the archaeological remains and the traditional knowledge of the indigenous peoples.

The modern interpretive center uses cutting-edge technology to bring the ancient hunting practices to life. Visitors can experience immersive displays that recreate the sights and sounds of a buffalo jump, complete with detailed explanations of the techniques and technologies involved.

The site also serves as a research center where archaeologists and anthropologists continue to unlock the secrets of this ancient hunting ground. New discoveries are constantly being made, adding to our understanding of how these sophisticated hunting systems operated and evolved over thousands of years.

Lessons for Modern Sustainability

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump offers profound lessons for modern society about sustainable resource management and community cooperation. The site operated successfully for over 6,000 years without depleting the buffalo populations or degrading the environment. This achievement stands in stark contrast to modern industrial practices that often exhaust resources within decades.

The complete utilization philosophy practiced at the site demonstrates how human communities can live in harmony with their environment while still meeting their material needs. The sophisticated social organization required for the buffalo jumps shows how cooperation and shared responsibility can achieve results that individual effort cannot match.

The site also demonstrates the importance of traditional ecological knowledge and the value of long-term thinking. The indigenous peoples who used Head-Smashed-In thought in terms of generations rather than years, creating systems that could adapt and evolve over millennia. These lessons are increasingly relevant as modern society grapples with climate change and resource depletion.

Conclusion: Where Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Understanding

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump stands as one of humanity’s most remarkable achievements in sustainable resource management and community cooperation. For over 6,000 years, this site provided sustenance for thousands of people while maintaining the delicate balance between human needs and environmental preservation. The sophisticated techniques developed here – from the engineering marvels of the drive lanes to the revolutionary food preservation methods – demonstrate that our ancestors possessed wisdom and skills that modern society is still trying to master.

The site’s transformation from an active hunting ground to a protected heritage site reflects our growing understanding of the value of traditional knowledge and the importance of preserving cultural landscapes. The lessons embedded in these ancient stone cairns and bone beds offer guidance for addressing contemporary challenges of sustainability, cooperation, and environmental stewardship.

As we face an uncertain future marked by climate change and resource scarcity, perhaps we should ask ourselves: what would our ancestors who built Head-Smashed-In think of our current approach to managing the Earth’s resources?