Standing on the bustling streets of modern Buenos Aires, it’s almost impossible to imagine that beneath the concrete and asphalt lies evidence of a world so alien it seems like science fiction. Yet just 10,000 years ago, this very landscape was home to creatures that would make today’s largest animals look like toys. Giant ground sloths the size of small cars shuffled across these plains, while armored beasts called glyptodonts rolled through ancient grasslands like living tanks. The transformation from this prehistoric menagerie to today’s urban sprawl represents one of the most dramatic ecological shifts in Earth’s history.

When Buenos Aires Was a Different World

The Buenos Aires region during the Pleistocene epoch, roughly 2.5 million to 11,700 years ago, bore little resemblance to the metropolitan area we know today. Instead of skyscrapers and highways, vast pampas stretched endlessly under South American skies, dotted with slow-moving rivers and seasonal wetlands. The climate was cooler and more variable than today, with ice ages alternating with warmer interglacial periods.

These ancient grasslands supported an ecosystem so rich and diverse that it rivaled Africa’s modern savannas. But unlike today’s wildlife, the creatures that roamed these plains were giants – megafauna that evolved in isolation on the South American continent for millions of years. The very ground beneath Buenos Aires holds their fossilized remains, telling stories of a lost world that vanished in what amounts to an evolutionary blink of an eye.

The Magnificent Megatherium: South America’s Gentle Giant

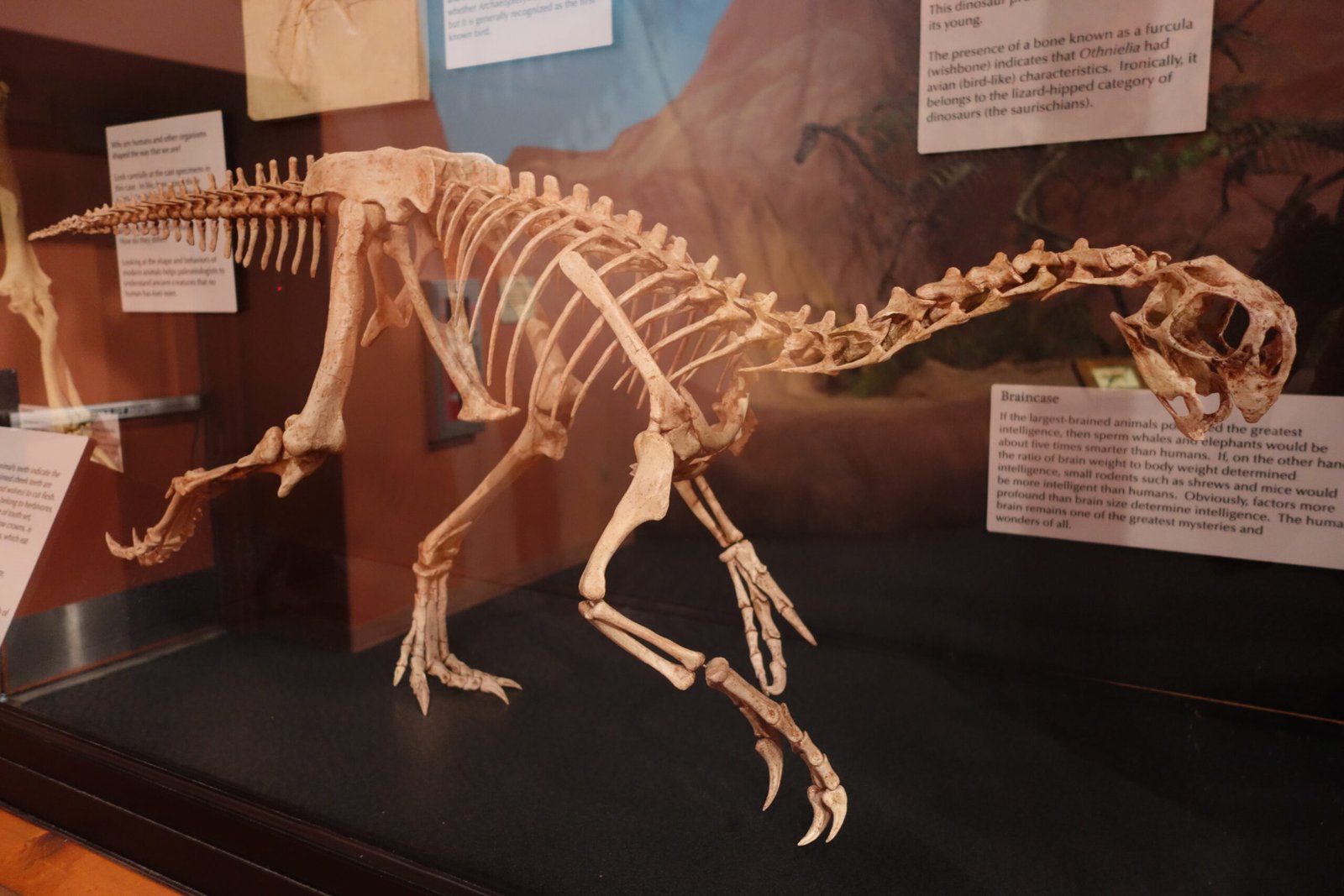

Among the most impressive residents of ancient Buenos Aires was Megatherium, a ground sloth that stood over 12 feet tall when rearing on its hind legs. Weighing up to 4 tons, this massive herbivore was roughly the size of a modern elephant but built like a bear crossed with a tank. Its powerful claws, each the length of a human forearm, weren’t designed for hunting but for stripping leaves from the tallest trees and digging up roots.

What made Megatherium truly remarkable wasn’t just its size, but its lifestyle. Unlike the tree-dwelling sloths we know today, these giants were terrestrial powerhouses that could rear up to reach vegetation 20 feet off the ground. Their fossilized remains, frequently discovered in Buenos Aires province, reveal a creature perfectly adapted to the open grasslands and scattered woodlands of Ice Age Argentina.

Glyptodon: Nature’s Living Fortress

If Megatherium was impressive for its size, Glyptodon was extraordinary for its armor. This car-sized armadillo relative looked like something from a medieval fantasy, encased in a dome-shaped shell made of interlocking bony plates. The shell alone could measure 10 feet long and was strong enough to protect the animal from the largest predators of its time.

But Glyptodon’s defensive strategy went beyond passive protection. Its tail was tipped with a massive, spiked club that could deliver devastating blows to any threat. Archaeological evidence from the Buenos Aires region suggests these creatures lived in small herds, their shells creating an almost impenetrable wall when they huddled together. The discovery of Glyptodon fossils in what is now downtown Buenos Aires reminds us that armor-plated giants once grazed where office buildings now stand.

Saber-Toothed Cats: The Ultimate Predators

Where there were giant herbivores, there were also giant predators to hunt them. Smilodon populator, the largest of the saber-toothed cats, stalked the Buenos Aires plains with canine teeth up to 7 inches long. These weren’t just oversized house cats – they were muscular, powerful hunters built specifically to take down megafauna.

Unlike modern big cats that kill with a crushing bite to the throat, Smilodon used its massive sabers to slash major blood vessels and windpipes. Their incredibly robust build, with forelimbs more powerful than any modern cat, allowed them to wrestle down prey many times their own weight. Fossil evidence from the region shows these apex predators successfully hunted everything from ground sloths to ancient horses, playing a crucial role in shaping the ecosystem’s dynamics.

The Terror Birds: Feathered Nightmares

Long before mammals dominated the South American landscape, massive flightless birds ruled as apex predators. Phorusrhacos, standing 8 feet tall with a skull the size of a horse’s head, was among the most formidable hunters ever to stalk the Buenos Aires region. These “terror birds” possessed razor-sharp beaks capable of crushing bones and tearing flesh with surgical precision.

What made these birds particularly terrifying was their speed and intelligence. Unlike the lumbering giants they sometimes hunted, Phorusrhacos could run at speeds approaching 30 miles per hour, using their powerful legs and sharp talons to pursue prey across the open plains. Their presence in the fossil record of Buenos Aires province reveals an ecosystem where the line between predator and prey was constantly shifting.

Doedicurus: The Mace-Tailed Titan

Among the most bizarre creatures to inhabit ancient Buenos Aires was Doedicurus, an armadillo relative that took defensive warfare to spectacular extremes. Measuring up to 12 feet long and weighing nearly 2 tons, this massive herbivore was essentially a living fortress on legs. But its most distinctive feature was its tail – a massive, flexible weapon tipped with a spiked club weighing over 100 pounds.

The discovery of Doedicurus fossils with damaged tail clubs suggests these animals engaged in violent intraspecies combat, possibly fighting for territory or mates. Imagine the thunderous crashes as these armored titans clashed on the ancient pampas, their massive clubs swinging through the air with bone-crushing force. Such battles would have been both terrifying and spectacular to witness.

The Giant Short-Faced Bear: South America’s Apex Predator

While Smilodon gets most of the attention, the true apex predator of Ice Age Buenos Aires may have been Arctotherium angustidens, the giant short-faced bear. Standing 11 feet tall on its hind legs and weighing up to 3,000 pounds, this massive omnivore was the largest terrestrial carnivorous mammal that ever lived. Its fossils, discovered throughout Argentina including the Buenos Aires region, reveal a creature built for both power and speed.

What made this bear so formidable wasn’t just its size, but its versatility. Unlike modern bears, Arctotherium had long legs built for running, allowing it to chase down prey across open grasslands. Its massive skull housed a brain large enough to make it a cunning hunter, while its powerful jaws could crush the bones of even the largest megafauna. In the ecosystem of ancient Buenos Aires, this bear was the undisputed king.

Toxodon: The Hippo-Rhino Hybrid

One of the strangest inhabitants of Ice Age Buenos Aires was Toxodon, a creature so unusual that Charles Darwin himself was baffled when he first encountered its fossils. Roughly the size of a modern rhino but built like a hippo, this massive herbivore had continuously growing teeth and a bizarre mix of features that seemed to defy classification. It wasn’t until modern genetic analysis that scientists confirmed Toxodon’s relationship to modern horses and tapirs.

Toxodon’s lifestyle was equally unique. These semi-aquatic giants spent much of their time in the rivers and wetlands that crisscrossed the Buenos Aires region, using their bulk and swimming ability to escape terrestrial predators. Their fossilized remains often show evidence of interactions with early humans, suggesting these creatures survived well into the human colonization of South America.

Macrauchenia: The Elephant-Camel of the Pampas

Perhaps no creature better exemplifies the bizarre nature of South American megafauna than Macrauchenia, an animal that looked like someone had mixed parts from a camel, elephant, and llama in a biological blender. Standing 6 feet tall at the shoulder with a flexible trunk and long, slender legs, this herbivore was perfectly adapted for life on the open plains of ancient Buenos Aires.

Recent studies of Macrauchenia fossils from the region have revealed surprising details about their lifestyle. Their trunk, while smaller than an elephant’s, was highly sensitive and used for both feeding and social communication. Their long legs made them excellent runners, capable of outpacing most predators across the flat grasslands. These adaptations made them one of the most successful megafauna species, surviving until the very end of the Pleistocene.

The Giant Beaver: Castoroides and Its Engineering Marvels

While most people associate giant beavers with North America, South America had its own impressive rodent engineers. Castoroides, though technically found further north, had relatives in the Buenos Aires region that transformed the landscape through their dam-building activities. These massive rodents, some weighing over 200 pounds, created complex waterway systems that supported entire ecosystems.

The engineering capabilities of these giant beavers were extraordinary. Their dams could span entire valleys, creating vast wetlands that provided habitat for countless other species. The impact of their activities on the Buenos Aires landscape was so significant that their decline may have contributed to major ecological changes throughout the region. Their fossils remind us that ecosystem engineers have always played crucial roles in shaping environments.

Hippidion: The Last of South America’s Horses

Before European colonization brought horses back to the Americas, South America was home to its own unique equids. Hippidion, a sturdy horse about the size of a modern pony, roamed the Buenos Aires plains in large herds. These horses had evolved in isolation for millions of years, developing characteristics unlike any modern horse breed.

What made Hippidion particularly interesting was its adaptation to South American conditions. Unlike their North American cousins, these horses had shorter, more robust builds that made them excellent at navigating varied terrain. Their social structure, revealed through bone bed discoveries in Buenos Aires province, shows they lived in complex herds with sophisticated communication systems. Their extinction represents the loss of millions of years of unique evolutionary history.

The Role of Climate Change in Megafauna Evolution

The megafauna of Buenos Aires didn’t evolve in a static environment. Throughout the Pleistocene, dramatic climate changes repeatedly reshaped the landscape, driving evolutionary innovation and adaptation. Ice ages alternated with warmer periods, causing sea levels to rise and fall, grasslands to expand and contract, and entire ecosystems to shift across the continent.

These climate fluctuations acted as evolutionary catalysts, pushing species to develop new survival strategies. The massive size of many megafauna species may have been an adaptation to cooler climates, as larger bodies retain heat more efficiently. Similarly, the elaborate defensive structures of animals like Glyptodon may have evolved in response to increasingly sophisticated predators during periods of ecological stress.

Human Arrival and the Beginning of the End

The story of Buenos Aires megafauna takes a dramatic turn around 15,000 years ago when the first humans arrived in South America. Archaeological evidence from the region shows that early human populations encountered and interacted with many megafauna species, fundamentally altering the ecological balance that had existed for millions of years.

The relationship between humans and megafauna was complex and varied. While hunting certainly played a role in some extinctions, humans also competed for resources, altered landscapes through fire use, and introduced diseases carried by domestic animals. The speed of megafauna extinction following human arrival – most species disappeared within just a few thousand years – suggests that these ecological pressures had devastating cumulative effects.

The Great Extinction Event

Between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago, the Buenos Aires region witnessed one of the most rapid and complete extinction events in Earth’s history. Over 80% of large mammal species vanished, transforming a landscape dominated by giants into the relatively small-animal ecosystem we see today. This wasn’t a gradual decline but a catastrophic collapse that occurred within just a few millennia.

The timing of these extinctions varied slightly between species, providing clues about their causes. The largest herbivores disappeared first, followed by the specialized predators that depended on them. Some species, like certain ground sloths, survived in remote areas until as recently as 4,000 years ago, suggesting that human pressure rather than climate change was the primary driver of extinction.

What makes this extinction event particularly tragic is its preventability. Unlike the asteroid impact that killed the dinosaurs, the Pleistocene extinctions were largely caused by the activities of a single species – us. The loss of these magnificent creatures represents not just a biological tragedy but a cultural one, as indigenous peoples lost animals that had been part of their world for thousands of years.

Fossil Discoveries That Shocked the World

The Buenos Aires region has been a treasure trove for paleontologists since the 19th century, yielding some of the most complete and spectacular megafauna fossils ever discovered. The famous Luján Formation, which extends through much of Buenos Aires province, has preserved an incredible record of Pleistocene life, including complete skeletons of ground sloths, glyptodonts, and saber-toothed cats.

One of the most significant discoveries occurred in the 1870s when Florentino Ameghino began systematically collecting fossils from the region. His work revealed the true diversity of South American megafauna and established Argentina as one of the world’s premier paleontological destinations. More recent discoveries, including the find of a complete Megatherium skeleton in 2009, continue to reveal new details about these ancient giants.

Perhaps most remarkably, construction projects in modern Buenos Aires regularly uncover megafauna remains. Subway excavations, building foundations, and road construction have all yielded significant fossils, creating a unique situation where paleontology and urban development intersect. These discoveries serve as constant reminders that the modern city sits atop one of the world’s greatest fossil deposits.

What These Giants Mean for Modern Conservation

The story of Buenos Aires megafauna isn’t just ancient history – it offers crucial lessons for modern conservation efforts. The rapid extinction of these species demonstrates how quickly ecosystems can collapse when faced with human pressure, providing a sobering preview of what we might lose in our current biodiversity crisis.

Modern Argentina faces similar challenges to those that confronted megafauna: habitat fragmentation, climate change, and competition with human activities. The country’s remaining large mammals, including jaguars, pumas, and giant anteaters, require the same vast territories and complex ecosystems that supported their ancient predecessors. Understanding what was lost helps us appreciate what we still have and work harder to preserve it.

Some scientists are even exploring the possibility of “rewilding” the Buenos Aires region with large mammals from other continents, using elephants and rhinos as ecological proxies for extinct ground sloths and toxodonts. While controversial, these proposals highlight the lasting impact of megafauna extinction on South American ecosystems and the challenges of restoring ecological function once key species are lost.

The Cultural Legacy of Lost Giants

The megafauna of Buenos Aires left more than just fossils – they left an indelible mark on human culture and imagination. Indigenous peoples throughout South America preserved stories and oral traditions about giant animals, many of which match remarkably well with what we now know about Ice Age megafauna. These cultural memories, passed down through thousands of years, represent one of humanity’s longest-running natural history records.

Even today, the memory of these ancient giants influences Argentine culture and identity. The glyptodont appears on Argentine currency, ground sloths feature in museum displays throughout Buenos Aires, and megafauna imagery is common in local art and literature. This cultural connection helps maintain public interest in paleontology and conservation, creating bridges between ancient and modern worlds.

The loss of megafauna also represents a loss of cultural possibilities. We’ll never know what relationships might have developed between humans and these giants given more time and different circumstances. The speed of their extinction cut short millions of years of evolutionary experimentation, leaving us to wonder what forms of cooperation, domestication, or coexistence might have been possible.

Modern Technology Reveals Ancient Secrets

Twenty-first-century technology is revolutionizing our understanding of Buenos Aires megafauna, revealing details about their lives that would have been impossible to discover just decades ago. DNA analysis of preserved specimens has clarified evolutionary relationships and revealed unexpected connections between species. For instance, genetic studies showed that Macrauchenia was more closely related to horses than to elephants, despite its trunk.

Computer modeling and biomechanical analysis have brought these creatures back to life in digital form, allowing scientists to study how they moved, fed, and interacted with their environment. These studies have revealed that many megafauna were more active and agile than previously thought, overturning old stereotypes about slow, lumbering giants. Advanced imaging techniques have even revealed soft tissue preservation in some fossils, providing unprecedented glimpses into megafauna anatomy and physiology.

Perhaps most excitingly, scientists are using environmental DNA analysis to search for genetic traces of megafauna in ancient sediments. This cutting-edge technique has already revealed the presence of extinct species in areas where no fossils have been found, potentially expanding our understanding of megafauna distribution and survival. Such discoveries continue to reshape our picture of Ice Age Buenos Aires and the creatures that once called it home.

The transformation of Buenos Aires from a land of giants to a modern metropolis represents one of the most dramatic ecological shifts in recent Earth history. The creatures that once roamed these plains – from massive ground sloths to armor-plated glyptodonts – evolved over millions of years only to vanish in mere millennia. Their disappearance serves as both a window into our planet’s incredible biological heritage and a warning about the fragility of the natural world.

The fossils buried beneath Buenos Aires streets tell a story that extends far beyond the city limits. They remind us that every landscape has a deep history, that the ground beneath our feet once supported entirely different forms of life. As we face our own environmental challenges, the fate of these ancient giants offers both inspiration for what nature can achieve and sobering lessons about what we stand to lose.

What other lost worlds lie hidden beneath the cities we inhabit every day?