Have you ever stood on a beach at midnight during a full moon, watching waves crash higher than they do at any other time? That mesmerizing sight is actually the result of one of nature’s most complex dance routines, where our Moon takes the lead role but the Sun is far from a silent partner. While most people know the Moon causes tides, the Sun’s role in shaping our ocean’s rhythm remains surprisingly underappreciated.

Understanding the Gravitational Dance

Our planet sits at the center of an invisible tug-of-war between two massive celestial bodies. The Sun — with about 27 million times the mass of the Moon — is always the gorilla in the room when it comes to solar system equations. But it’s a distant gorilla, about 390 times farther away than the Moon, which gives it a little less than half of the Moon’s tide-generating force. This distance factor is crucial because tidal forces don’t just depend on mass — they depend even more dramatically on proximity. Tidal generating forces vary inversely as the cube of the distance from the tide-generating object. This means that the sun’s tidal generating force is reduced by 3903 (about 59 million times) compared to the tide-generating force of the moon. Therefore, the sun’s tide-generating force is about half that of the moon, and the moon is the dominant force affecting the Earth’s tides. It’s like having a heavyweight boxer throwing punches from across the room versus a middleweight fighter standing right next to you — proximity wins every time.

How Tidal Forces Actually Work

The magic happens because gravity isn’t uniform across our planet’s surface. Tides are not caused by the gravitational forces of the Moon or the Sun lifting up the oceans—their gravitational pull is much too weak for that. Rather, tides are created because the strength and direction of the gravitational pull varies depending on where on Earth you are. This variation creates the differential forces or tidal forces that in turn cause tides. The tidal forces of the Moon are much stronger than the Sun’s because it is so much closer to our planet, causing a much greater variation in the gravitational force from one location to another. Imagine squeezing a stress ball unevenly — that’s essentially what both the Moon and Sun do to Earth’s oceans. The Moon’s gravitational pull on Earth, combined with other, tangential forces, causes Earth’s water to be redistributed, ultimately creating bulges of water on the side closest to the Moon and the side farthest from the Moon. The result? Two oceanic bulges that chase each other around our planet as Earth spins beneath them.

The Two-Bulge Mystery Explained

One of the most counterintuitive things about tides is why there’s a bulge on both sides of Earth — the side facing the Moon and the side facing away from it. But then why – on the opposite side of Earth – is there another tidal bulge, in the direction opposite the moon? It seems counterintuitive, until you realize that this second bulge happens at the part of Earth where the moon’s gravity is pulling the least. Think of it this way: the Moon pulls hardest on the water closest to it, pulls moderately on Earth’s center, and pulls weakest on the water farthest away. Both the moon and the Earth undergo a deformation along the line joining them, however, it is the fluid masses of the oceans that undergo the most significant deformations with the formation of a swelling. In addition to the swelling along the joining line, a diametrically opposite one on the other side of the Earth is formed due to the centrifugal force. The water on the far side essentially gets “left behind” as Earth and the nearby water get tugged toward the Moon.

Solar Tides: The Sun’s Quieter Contribution

The Sun, too, pulls more strongly on the noon-side of the Earth, and more weakly on the midnight side, than it does on Earth’s center. It, too, creates a tidal force that, on its own, would cause two bulges in the ocean. If there were no Moon, we’d still have twice daily tides, just smaller ones and always at the same time of day. The Sun’s tidal influence is remarkably consistent compared to the Moon’s ever-changing pull. Solar tides are about half as large as lunar tides and are expressed as a variation of lunar tidal patterns, not as a separate set of tides. In fact, the height of the average solar tide is about 50% of the average lunar tide. Without the Moon, our tides would be boringly predictable — high tide at noon and midnight, low tide at 6 AM and 6 PM, every single day without variation.

When the Sun and Moon Align: Spring Tides

Magic happens when our cosmic partners decide to work together. When the sun, moon, and Earth are in alignment (at the time of the new or full moon), the solar tide has an additive effect on the lunar tide, creating extra-high high tides, and very low, low tides—both commonly called spring tides. These aren’t named after the season — A spring tide is a common historical term that has nothing to do with the season of spring. Rather, the term is derived from the concept of the tide “springing forth.” Spring tides occur twice each lunar month all year long without regard to the season. Twice a month, when the Earth, Sun, and Moon line up, their gravitational power combines to make exceptionally high tides where the bulges occur, called spring tides, as well as very low tides where the water has been displaced. Think of it as two friends pushing a swing together — the combined effort creates much higher swings than either could achieve alone.

When Forces Compete: Neap Tides

But celestial teamwork doesn’t last forever. About a week later, when the Sun and Moon are at right angles to each other, the Sun’s gravitational pull works against the Moon’s gravitational tug and partially cancels it out, creating the moderate tides called neap tides. During these times, the bulge of the ocean caused by the sun partially cancels out the bulge of the ocean caused by the moon. This produces moderate tides known as neap tides, meaning that high tides are a little lower and low tides are a little higher than average. During neap tides, the gravitational forces of the Moon and the Sun partially cancel each other out. The Sun’s gravitational pull is at right angles to the Moon’s. The result is a lower high tide and a higher low tide. Neap tides have the smallest tidal range. It’s like two people pulling a rope in different directions — neither gets to pull as hard as they could alone.

The Timing Game: When Tides Don’t Follow the Rules

Here’s where things get fascinatingly complicated. Earth’s tidal bulges don’t line up exactly with the Moon’s position. Earth’s spin carries the tidal bulge forward (Earth’s spin being much faster than the Moon’s orbital period). This means that the high tide bulges are never directly lined up with the Moon, but a little ahead of it. Earth spins once every 24 hours. So, a given location on Earth will pass “through” both bulges of water each day. Of course, the bulges don’t stay fixed in time. They move at the slow rate of about 13.1 degrees per day. That’s the same rate as the monthly motion of the moon relative to the stars. This cosmic lag means predicting exact tide times requires understanding not just where the Moon is, but where it was and where it’s going.

Distance Matters: The Elliptical Effect

Both the Moon and Earth follow elliptical, not circular, paths around their cosmic partners. Because the moon follows an elliptical path around the Earth, the distance between them varies by about 31,000 miles over the course of a month. Once a month, when the moon is closest to the Earth (at perigee), tide-generating forces are higher than usual, producing above-average ranges in the tides. About two weeks later, when the moon is farthest from the Earth (at apogee), the lunar tide-raising force is smaller, and the tidal ranges are less than average. A similar situation occurs between the Earth and the sun. When the Earth is closest to the sun (perihelion), which occurs about January 2 of each calendar year, the tidal ranges are enhanced. When the Earth is furthest from the sun (aphelion), around July 2, the tidal ranges are reduced. These orbital dances mean that no two spring tides are exactly the same — some pack more punch than others.

Supermoons and King Tides: When Everything Aligns

Occasionally, nature puts on a real show. When the new moon or full moon closely aligns with perigee – the closest point to Earth in the moon’s orbit – then we have a supermoon and extra-large spring tides. The highest tides – sometimes called perigean tides, or king tides or even supermoon tides – tend to fall on the day or so after a new or full supermoon. Not all spring tides are the same size. Springs nearest the equinoxes (21 March and 21 September – when day and night are of equal length all over the world) are slightly bigger. These exceptional tides can catch coastal communities off guard, flooding areas that normally stay dry and creating spectacular displays of nature’s power.

The Geography Factor: Why Location Changes Everything

The simple sun-moon-Earth equation gets dramatically complicated when you add continents, ocean basins, and underwater topography to the mix. Of course, in reality the Earth isn’t a smooth ball, so tides are also affected by the presence of continents, the shape of the Earth, the depth of the ocean in different locations, and more. The timing and heights of the tide near you will be affected by those additional elements. However, the variation between high and low tide is very different from place to place. It can range from almost no difference to over 16 meters (over 50 feet). This is because the water in the oceans is constrained by the shape and distance between the continents as well as varying ocean depths. Geography also affects the tidal range. Looking at tide tables for all of Britain, it’s clear that the height of the tide varies around the country. For example the spring tidal range at Avonmouth is 12.2m while at Lowestoft it’s only 1.9m. The Bay of Fundy in Canada experiences tides up to 50 feet high, while some locations in the Mediterranean see barely noticeable tidal changes.

Tidal Heating: The Hidden Energy Source

The constant stretching and squeezing from tidal forces doesn’t just move water — it generates heat deep within planetary bodies. Tidal heating occurs through the tidal friction processes: orbital and rotational energy is dissipated as heat in either (or both) the surface ocean or interior of a planet or satellite. When an object is in an elliptical orbit, the tidal forces acting on it are stronger near periapsis than near apoapsis. Thus the deformation of the body due to tidal forces varies over the course of its orbit, generating internal friction which heats its interior. This energy gained by the object comes from its orbital energy and/or rotational energy. Munk & Wunsch (1998) estimated that Earth experiences 3.7 TW (0.0073 W/m2) of tidal heating, of which 95% (3.5 TW or 0.0069 W/m2) is associated with ocean tides and 5% (0.2 TW or 0.0004 W/m2) is associated with Earth tides, with 3.2 TW being due to tidal interactions with the Moon and 0.5 TW being. This might sound tiny, but it’s enough energy to power several large cities continuously.

The Slowing Dance: How Tides Change Time

Here’s something that might blow your mind: the tides are gradually slowing down Earth’s rotation. This same effect is also slowing Earth’s rotation very slightly, resulting in longer days! Tidal acceleration occurs between a moon and a planet. Over time, tidal acceleration causes a moon to slowly move away if it is orbiting in the same direction as the planet’s rotation. This also gradually slows the planet’s rotation and lengthens its day. This is slowly happening between the Earth and Moon. The energy dissipated through tidal friction is borrowed from Earth’s rotational energy, making our days about 2 milliseconds longer each century. In the process, the Moon drifts about 1.5 inches farther from Earth each year. Millions of years ago, days were significantly shorter and the Moon appeared much larger in our sky.

Solar System Showcase: Tidal Forces Beyond Earth

Earth isn’t the only world experiencing tidal drama. Tidal heating is responsible for the geologic activity of the most volcanically active body in the Solar System: Io, a moon of Jupiter. The amount of heat escaping per square metre of Io’s surface is over a hundred times that escaping from the Moon, and about 25 times that escaping from the Earth. So what’s causing all this heating responsible for resurfacing Io and many of the icy satellites? Well, the answer appears to lie in the orbital interactions of satellites moving around extremely massive planets. Saturn’s moon Enceladus is similarly thought to have a liquid water ocean beneath its icy crust, due to tidal heating related to its resonance with Dione. The water vapor geysers which eject material from Enceladus are thought to be powered by friction generated within its interior. These moons experience the ultimate version of our tidal heating, with Jupiter and Saturn acting as cosmic furnaces that keep their satellites geologically active billions of years after they should have frozen solid.

Predicting the Unpredictable: Why Tide Tables Exist

Given all these competing factors, you might wonder how anyone predicts tides at all. Can you easily predict the tides by following the path of the Moon? Not really! First of all, because the Moon is orbiting in the same direction as the Earth rotates, it takes extra time for any point on our planet to rotate and end up exactly below the Moon. The extra time is ~50 mins. Weather which can have a profound effect on the tide, is impossible to predict when calculating tide tables. Strong winds and abnormal atmospheric pressure are two of the main causes of altered tides. Other factors, including the shape of coastlines, also influence the time of the tides, which is why people who live near coastlines like to have a good tide almanac. The sun, the moon, the shape of a beach, the angle of the seabed leading up to land, and the prevailing ocean currents and winds all affect the height of the tides. Modern tide prediction combines centuries of observation with sophisticated computer models that account for dozens of variables.

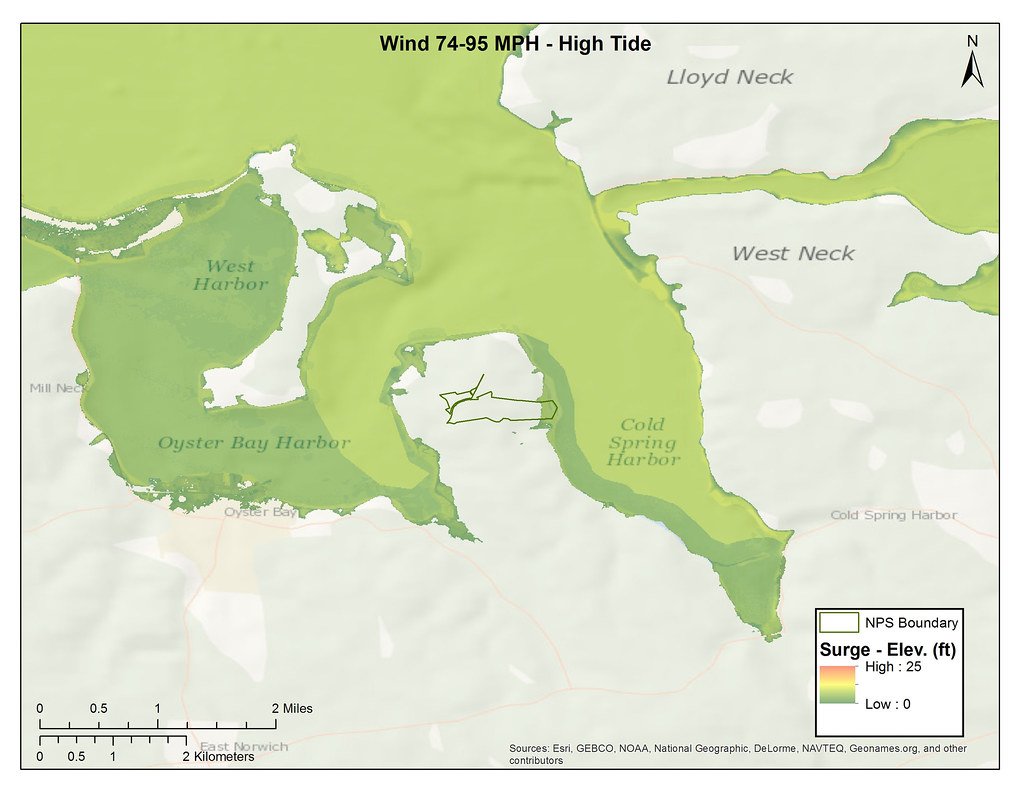

Climate and Weather: The Wild Cards

Even the best tide predictions can be thrown off by Mother Nature’s mood swings. Storm surges can add several feet to predicted high tides, while high atmospheric pressure can suppress them. Seasonal changes in water temperature affect ocean density, which influences how tides behave. Climate change is already altering long-term tidal patterns as sea levels rise and weather patterns shift. Some coastal areas are experiencing “sunny day flooding” during king tides — flooding that occurs even without storms, simply because the combined astronomical forces push water levels beyond the capacity of aging storm drainage systems.

The Future of Tidal Understanding

Our understanding of tidal mechanics continues to evolve with new technology and longer observational records. Satellite altimetry now allows scientists to measure ocean surface heights with millimeter precision across the globe. Advanced computer models can simulate tidal behavior under different climate scenarios, helping coastal communities prepare for future changes.