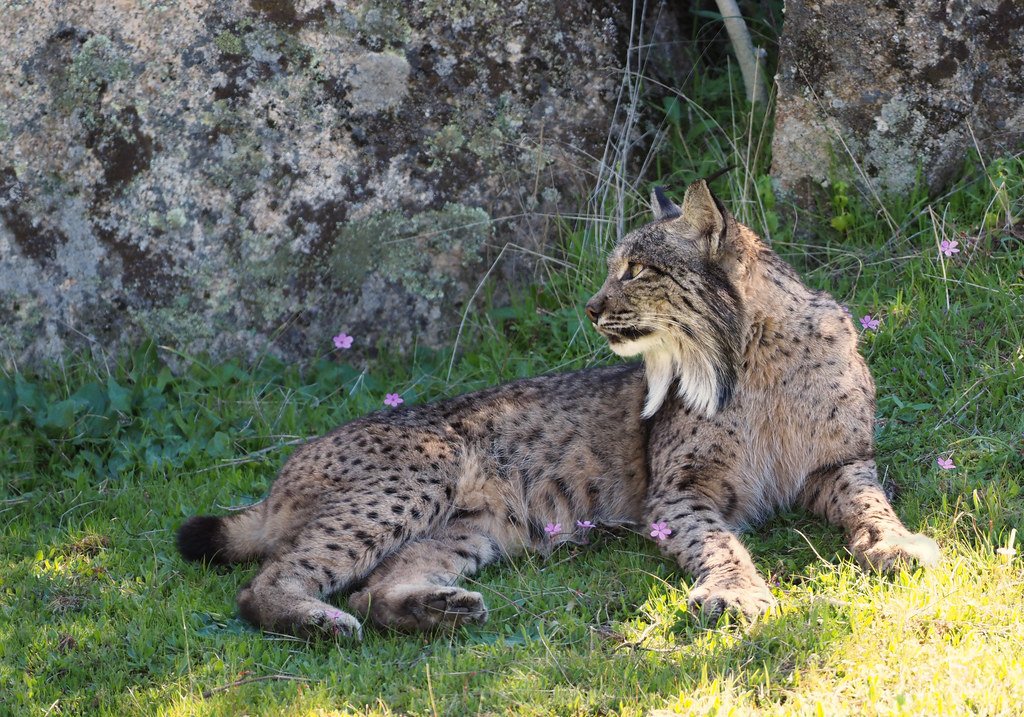

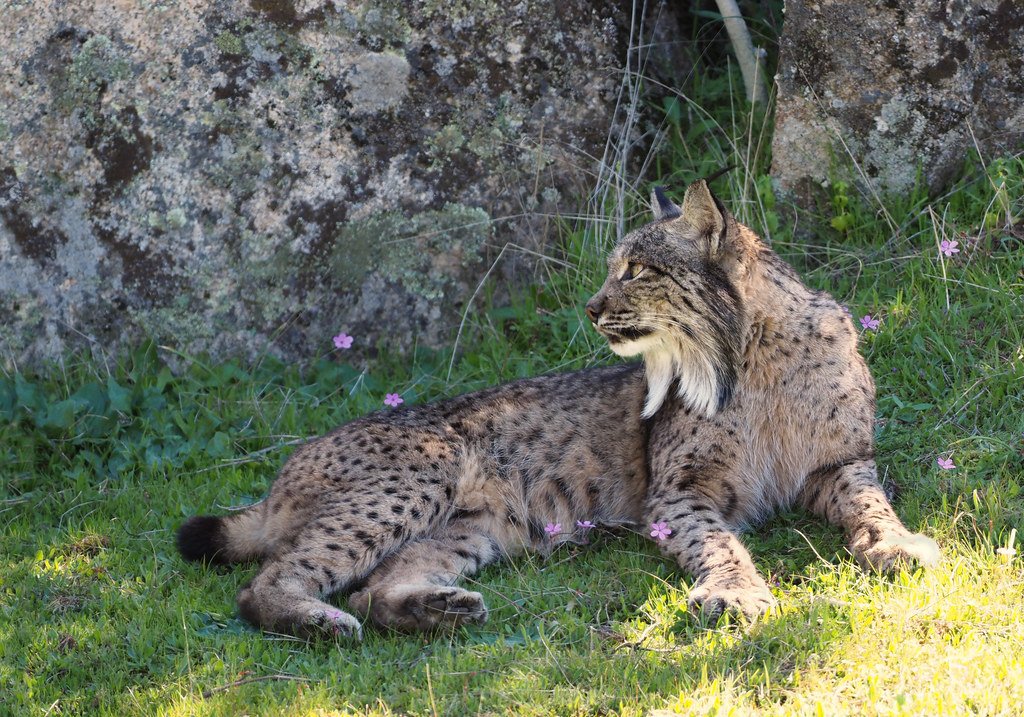

In the oak forests and rolling hills of southern Spain, something extraordinary is happening. The piercing yellow eyes that once flickered like dying embers in the Mediterranean scrubland are now blazing bright again. The Iberian lynx, Europe’s most endangered wild cat, has staged one of the most remarkable wildlife comebacks in modern conservation history. But this isn’t just another feel-good story about saving a species – it’s a testament to what happens when science, passion, and sheer determination collide with purpose.

The Ghost Cat’s Near Disappearance

Picture this: Just over two decades ago, the Iberian Lynx was down to fewer than 50 mature animals in two tiny locations in the Andalusia region of Spain. By 2002, this scene was almost extinct from our world forever. The Iberian lynx was literally counting down its final days, with fewer than 100 individuals remaining by 2002, making it the most endangered wild cat on Earth. Imagine walking through the forests of Doñana or Sierra Morena and knowing that every spotted shadow you glimpsed might be one of the last. Years of declining wild rabbit populations, habitat destruction, inbreeding and deaths from ‘non-natural’ causes – including hunting and roadkills – had left the species teetering on the brink of extinction. The ghost cat was becoming an actual ghost, and Spain was about to lose one of its most iconic predators forever.

Andalusia’s Sanctuary Regions

The best populations of Iberian lynx, Europe’s big cat, can be found in the Andalusian Sierra Morena. It was declared an endangered species in 1986 and critically endangered in 2002, due to its reduced presence throughout the Iberian peninsular. But as a result of the enormous efforts being made for their protection and recovery in our Community, there has been a significant increaser in the number of individuals, as well as their dispersion and home ranges. The Nature Reserves of Andújar and Despeñaperros, in the province of Jaén, and Cardeña-Montoro, in the province of Córdoba, are essential refuges for the protection of this great Mediterranean feline. These weren’t just random patches of wilderness – they were carefully chosen strongholds where the lynx could find the perfect combination of prey, shelter, and protection from human interference. Today, The Sierra de Andújar in Jaén province which holds the largest population of this elusive feline. So we have this tour that maximizes the chances to watch Iberian Lynx in Andújar while enjoying one of the best preserved iberian oak forests and its general wildlife.

The Breeding Centers Revolution

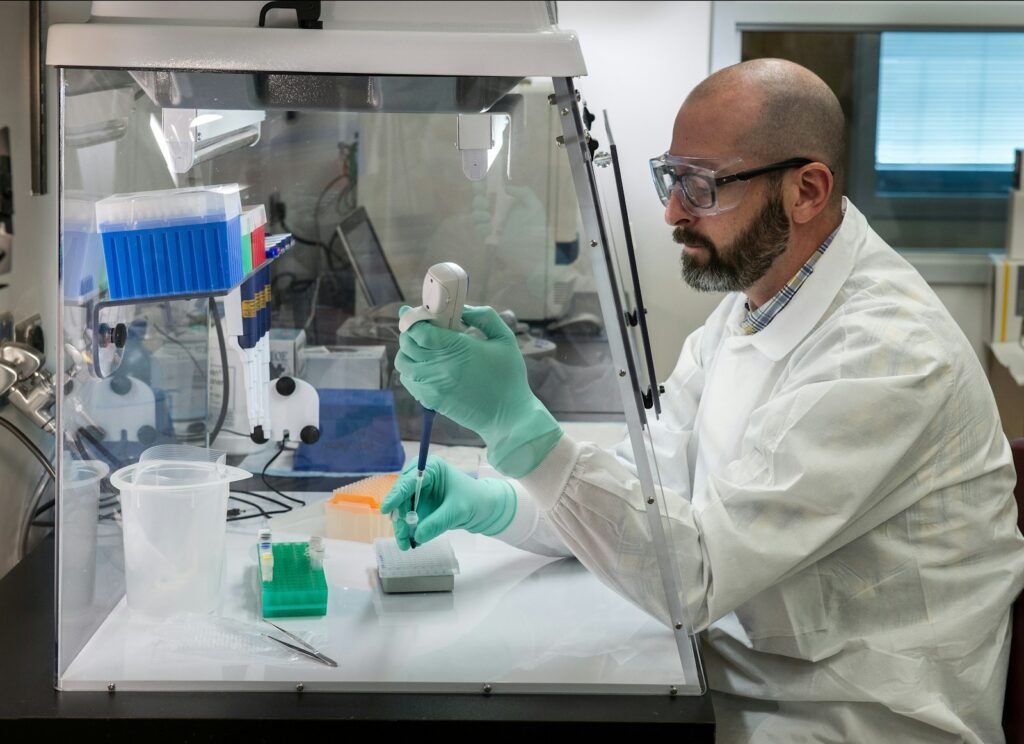

She became the first Iberian lynx to breed in captivity, giving birth to three healthy kittens on 29 March 2005 at the El Acebuche Breeding Center, in the Doñana National Park in Huelva, Spain. On March the 28th of 2005, round about 8p.m., Saliega, Iberian lynx female from the population of the Sierra Morena, gave birth to the first Iberian lynx litter born in captivity. This achievement meant a great step forwards for the conservation and recovery actions of the species. The captive breeding efforts took place at five specific locations: El Acebuche, La Olivilla, Silves, Zarza de Granadilla, and Zoobotánico de Jerez. These facilities played a crucial role in breeding and maintaining a captive population of Iberian lynxes, which contributed to increasing their numbers and genetic diversity. Think of these centers as five-star maternity wards for endangered cats, where every birth was celebrated like a small miracle because it literally was one.

El Acebuche: The Pioneer Center

“El Acebuche” was built attached to the Wildlife Recovery Center of the Doñana National Park. It wasn’t until the end of 2003, with the agreement signed between the “Ministerio de Medio Ambiente” and the “Consejería de Medio Ambiente de la Junta de Andalucía”, that the Ex Situ Conservation Program of the Iberian Lynx started off at this complex. Currently “El Acebuche” acts as the coordinator center of the Breeding Centers Group for the Iberian Lynx Ex Situ Conservation Program. Located in the heart of Doñana, this facility became the nerve center of the entire captive breeding operation. It’s like the headquarters of hope, where scientists tracked lineages, monitored genetics, and planned the strategic expansion of the lynx population with military precision.

La Olivilla: The Largest Breeding Complex

“La Olivilla” is the largest of all centers that are comprised in the Iberian Lynx Captive Breeding Program Group. It has 23 enclosures with a surface of about 1250m2 for each, each containing autochthon vegetation. The center also includes five other buildings intended for laboratory and clinic room, hand rearing room, office, quarantines and staff lodgings. Nestled in the mountains near Santa Elena in Jaén, La Olivilla wasn’t just bigger – it was designed to replicate the wild as closely as possible. As part of the official reintroduction calendar led by the Consejería de Desarrollo Sostenible, several lynxes were recently released into the wild: February 2025: Valença (female, born at El Acebuche), Icaro (wild-born male translocated from Sierra Morena), and Veloz (male, born at La Olivilla) were released. Each massive enclosure gave lynx families room to roam, hunt, and behave naturally while still under human protection.

Portugal Joins the Fight

The Iberian Lynx National Breeding Center (Silves’ Center) was inaugurated in May 2009 and received its first Iberian lynx specimen, Azahar, a female from the “Zoobotánico de Jerez”, on October the 26th. In Portugal, the Centro Nacional de Reprodução do Lince-Ibérico established a breeding center near Silves, Portugal, and has since nurtured 122 individuals all born in the breeding center, of which 89 survived. Portugal’s entry into the breeding program wasn’t just neighborly cooperation – it doubled the genetic diversity and provided crucial backup populations. In 2015, 10 captive-bred Iberian lynxes were released into Guadiana Valley Natural Park and surrounding areas in southeastern Portugal’s Guadiana Valley. The reintroduction of Iberian lynx in Portugal has been a success; from 17 animals that were reintroduced, 12 have already established territories.

The Rabbit Crisis That Almost Killed Everything

According to estimates, the wild rabbit population in the United Kingdom fell by 99%, in France by 90% to 95%, and in Spain by 95%. This in turn drove specialized rabbit predators, such as the Iberian lynx and the Spanish imperial eagle, to the brink of extinction. Myxomatosis is a viral disease that affects European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) worldwide. In Spain, populations of wild rabbits drastically decreased in the 1950s after the first outbreak of myxomatosis. Since that first appearance, it seems to be an annual epizootic in Spain with periodic outbreaks, predominantly in summer and autumn. It’s like watching the foundation of a house crumble – when the rabbits disappeared, everything built on top of them started collapsing. The Iberian lynx preys foremost on the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) for the bulk of its diet, supplemented by red-legged partridge (Alectoris rufa), rodents and to a smaller degree also on wild ungulates. A male requires one rabbit per day, while a female raising kittens eats three per day. The Iberian lynx has low adaptability and continued to rely heavily on rabbits, which account for 75% of its food intake, despite the latter’s repeated population crashes due to myxomatosis and rabbit haemorrhagic disease.

Fighting Two Viral Enemies

The emergence of myxomatosis and RHD (i.e., GI.1) in the twentieth century, as well as the recent new RHD strain outbreak in 2010 (i.e., GI.2), have been the primary determinants for the decline of wild European rabbits within their native range (e.g., [3,12,45]). According to our findings, rabbit populations in Spain showed a positive trend in the years before the first outbreak of GI.1, when rabbit numbers dropped by around 53%. The observed negative trend at a national level primarily responds to declines in two large regions where nearly 60% of the hunted animals proceed: Andalusia and Castille La Mancha. Rabbit populations, already decimated by viral hemorrhagic disease and myxomatosis, continue to fluctuate unpredictably, directly impacting lynx diet and fertility. It’s like trying to feed your family when the grocery store keeps getting wiped out by natural disasters – just when the rabbits start recovering, another viral wave hits them. But two contagious viral diseases (particularly myxomatosis) have decimated the population. Whenever the rabbit population grows significantly, another virus strain strikes back and reduces the number of prey animals for the cats. Rabbit restocking programmes are now underway in many areas.

The Road to Recovery Begins

The recovery of the Iberian lynx officially began with the creation of the program Life of the Andalusian Lynx in 2002. This project was partly funded by the programme Life of the European Union, a key initiative in the conservation of biodiversity in Europe. All this was possible with the help of the Life+IBERLINCE conservation programme which received more than 70 million euro of which half of it was given by the EU and got help more than 20 organization. This wasn’t just throwing money at a problem – it was a coordinated European effort that brought together scientists, governments, NGOs, and local communities. About 90 million euros was spent on various conservation measures between 1994 and 2013. The European Union contributes up to 61% of funding. The scale of investment showed that Europe was serious about not letting this species disappear on its watch.

Reintroduction: The Great Homecoming

In 2010, the first reintroduction of lynxes was carried out in Córdoba and a year later it was repeated in Jaén. Beginning in 2009, the Iberian lynx was reintroduced into Guadalmellato, resulting in a population of 23 in 2013. Since 2010, the species has also been released in Guarrizas. In April 2013, it was reported that Andalusia’s total wild population—only 94 in 2002—had tripled to 309 individuals. These weren’t random releases – scientists carefully selected locations with healthy rabbit populations, suitable habitat, and community support. Officials release captive-bred lynx in areas of appropriate habitat, rabbit abundance, and acceptance by the local human population. It’s like finding the perfect apartment for your cat, except the apartment is hundreds of square kilometers of Mediterranean wilderness.

Expanding Territories: Beyond Andalusia

Now, thanks to the work of multiple LIFE projects over 20 years, Iberian Lynx are expanding into other regions such as Extremadura, Castilla La Mancha and Murcia in Spain, and Alentejo in Portugal. In 2025, Castilla-La Mancha reinforced its commitment to lynx conservation with the establishment of a new reintroduction zone in La Veguilla and Sierra Jarameña in Cuenca, making it the fifth stable lynx population in the region after Montes de Toledo, Sierra Morena (Eastern and Western), and Campos de Hellín. In addition to this population in Portugal, there are others in the Spanish regions of Castile-La Mancha (942 lynxes), Andalusia (836), Extremadura (254) and Murcia (15), some of which already have interconnection centers between them. There are now 17 different geographic areas in which the species reproduces. The lynx was reclaiming its ancestral homeland, one territory at a time, like a slow-motion conquest of hope.

The Numbers That Made History

The number of lynx in the Iberian Peninsula increased by 19% in 2024 and reached 2,401 animals, according to the annual census carried out by Spanish and Portuguese entities that are part of the species recovery project. In just four more years, that number more than doubled to 2,401 individuals. To put this in perspective, this growth averages nearly 29% per year, reflecting the success of coordinated conservation between Spain, Portugal, and the European Union. These aren’t just statistics – they represent individual lynx mothers, fathers, and cubs that exist today because of human determination. In 2024, 2,047 lynxes were identified in Spain and 354 in Portugal, in the Guadiana Valley (there were 291 in the previous census). Every single one of these animals represents a small victory against extinction, a life that wouldn’t exist without the extraordinary conservation effort.

International Recognition: From Critically Endangered to Vulnerable

In 2015, the IUCN Red List down-listed the Iberian lynx from Critically Endangered to Endangered, and in June this year from Endangered to Vulnerable. Gland, Switzerland, 20 June 2024 (IUCN) – The Iberian Lynx has improved from Endangered to Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™, continuing its dramatic recovery from near extinction thanks to sustained conservation efforts. The Iberian lynx is no longer classified as endangered, with one group calling it the “greatest recovery of a cat species ever achieved through conservation.” Francisco Javier Salcedo Ortiz, the coordinator of the LIFE Lynx-Connect project in Andalusia, Spain, said in a statement that the efforts have resulted in the “greatest recovery of a cat species ever achieved through conservation.” These aren’t just bureaucratic classifications – they represent milestones on the road back from the brink of extinction.

The Breeding Female Milestone

A crucial milestone in 2024 was the increase in territorial or breeding females, now totaling 470—up by 64 from 2023. The long-term goal is to reach 750 breeding females, a benchmark for favorable conservation status under IUCN guidelines. Think of breeding females as the engine of population growth – they’re the mothers who will produce the next generation of lynx. With 470 breeding females now recorded, the species is nearing its recovery target—yet high road mortality and habitat fragmentation remain key challenges. Each breeding female represents not just one life saved, but potentially dozens of future lynx cubs. The average litter size is 3, but it is rare for 3 Iberian lynx cubs to survive weaning—mortality rates are high. Kits become independent at 7 to 10 months old but remain with the mother until around 20 months old. The survival of the young depends heavily on the availability of prey species.

The Persistent Road Kill Crisis

In 2024, 214 lynx deaths were recorded—75.4% (162 deaths) caused by vehicle collisions. Despite all the success, one enemy remains particularly stubborn: our roads. In 2024, these paved barriers continued to fragment habitats, cutting across vital migration routes and hunting grounds, leaving lynx vulnerable as they attempt to navigate their shrinking territory. While conservation efforts have led to population recoveries in some regions, the growing network of roads has become a deadly obstacle that threatens to undo this progress. Without expanded wildlife crossings, fencing, and traffic calming measures in high-risk areas, vehicle collisions will remain a leading cause of mortality, undermining decades of work to protect and restore this elusive predator.