Picture this: You’re standing in what is now the world’s largest hot desert, but instead of endless dunes and scorching sun, you’re surrounded by vast grasslands swaying in a gentle breeze. Hippos splash in crystal-clear lakes, elephants trumpet as they move across the savannah, and ancient hunters track giraffes through acacia forests. This isn’t science fiction — this was the Sahara Desert just 6,000 years ago.

When the Desert Was Paradise

The African Humid Period transformed northern Africa from a hyperarid wasteland into a verdant landscape between roughly 14,800 and 5,500 years ago. Think about that for a moment — while our ancestors were building the first civilizations, the Sahara wasn’t a barrier between North and sub-Saharan Africa. During its green phase, monsoon rains increased dramatically, huge lakes appeared, and the entire region turned into savanna similar to what we see today in Kenya or Rwanda, with Lake Chad alone reaching the size of the current Caspian Sea. The transformation was so complete that scientists now call this period the “Green Sahara,” and honestly, it makes our current climate debates look like child’s play.

The Orbital Dance That Controls Our Planet

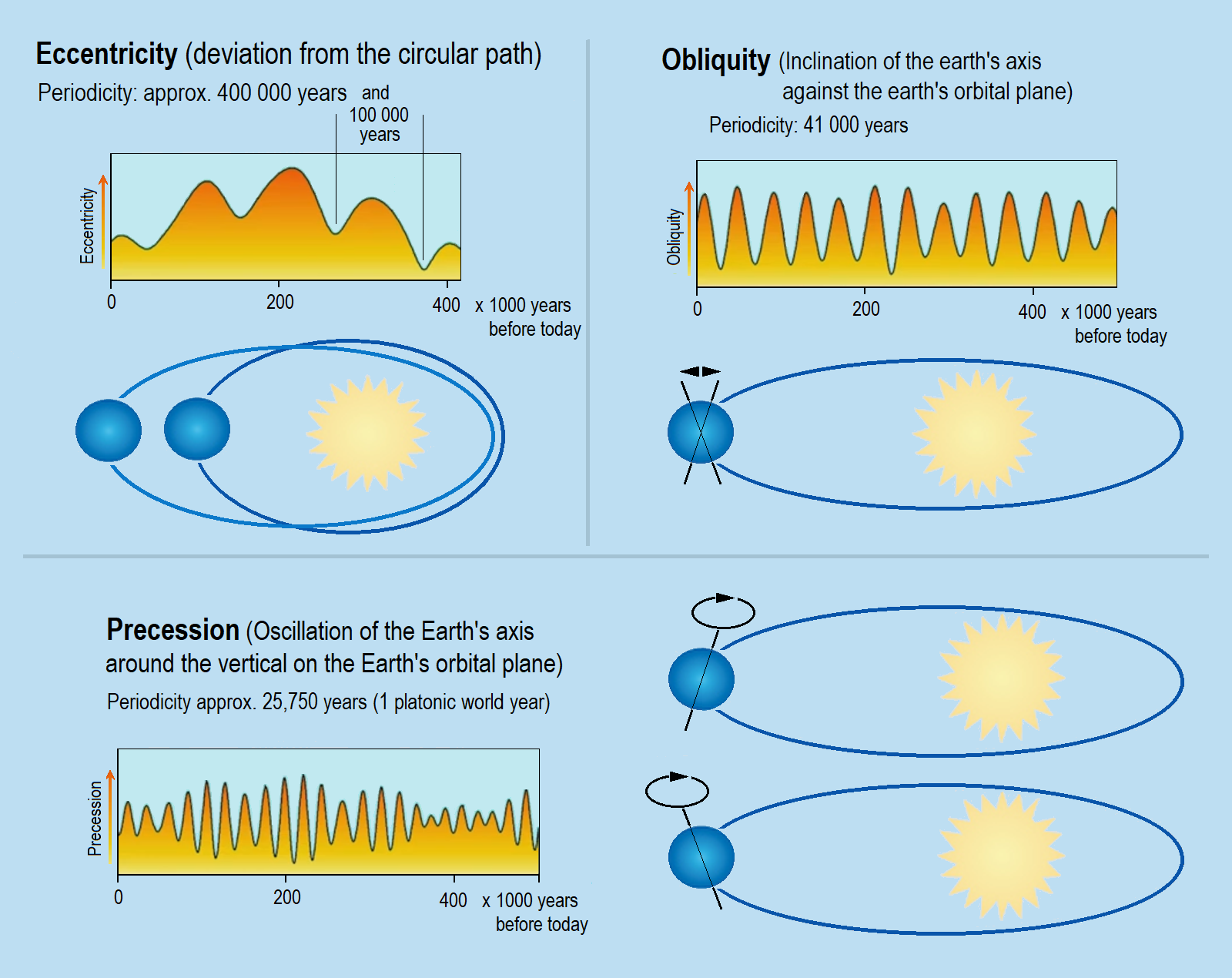

Earth’s constantly changing orbital rotation around its axis follows a pattern that repeats every 23,000 years, caused by gravitational interactions with the moon and massive planets. It’s like a cosmic clockwork that’s been ticking for millions of years, occasionally throwing our planet’s climate system completely out of whack. Changes in Earth’s axial tilt, combined with vegetation and dust feedback in the Sahara, strengthened the African monsoon and increased greenhouse gases, covering much of the desert with grasses, trees, and lakes. The sheer scale of this orbital influence is mind-boggling — imagine if changing your morning routine could alter the weather for thousands of years. These North African Humid Periods are astronomically paced by precession, which controls the intensity of the African monsoon system, with their amplitude strongly linked to eccentricity through its control over ice sheet extent.

Giants Walked Among Ancient Lakes

The Sahara has a continuous record of human habitation, from the giant Kiffians who lived there from 10,000 to 6,000 BC and whose skeletons measure 6 feet 6 inches tall, to the shorter Tenerians who spread across the region from 5,000 to 2,500 BC. These weren’t just random wanderers — they were sophisticated societies living in a landscape that would make today’s conservationists weep with joy. Rock art masterfully depicts pastoral scenes with abundant elephants, giraffes, hippos, aurochs, and antelope, occasionally being pursued by bands of hunters. The artwork alone tells a story that seems impossible when you look at the barren landscape today, but the evidence is literally carved in stone.

Megalakes That Dwarfed Today’s Great Waters

Ancient megalakes covered vast areas, with one prehistoric lake formed when the Nile River flooded the eastern Sahara 250,000 years ago, covering more than 42,000 square miles at its highest level, while Megalake Chad at its maximum extent had an area of about 340,000 square kilometers — only 8% smaller than today’s Caspian Sea. Try to wrap your head around that — we’re talking about bodies of water so massive they would make the Great Lakes look like puddles. The African Humid Period featured a network of vast waterways consisting of large lakes, rivers, and deltas, with the four largest being Lake Megachad, Lake Megafezzan, Ahnet-Mouydir Megalake, and Chotts Megalake. Satellite data has detected 2,300 kilometers of remains marking ancient shorelines, along with many Saharan rivers and relict deltas leading to these paleoshorelines. The geological evidence is so overwhelming that even the most skeptical scientists can’t deny these aquatic giants once existed.

The Art Gallery Hidden in Plain Sight

The Sahara is very likely the world’s largest art museum, with hundreds of thousands of elaborate engravings and paintings adorning rocky caves and outcrops, bearing testimony to a state of life very different from what we see in these regions today. Walking through these ancient galleries feels like stepping into a time machine — every cave painting and rock carving screams of a world where water was abundant and life flourished. Archaeological sites contain artifacts such as one of the oldest ships in the world and rock paintings like those in the Cave of Swimmers and the Acacus Mountains, with earlier humid periods postulated after the discovery of these rock paintings in now-inhospitable parts of the Sahara. These aren’t just pretty pictures — they’re historical documents that prove beyond doubt that our planet’s largest desert was once teeming with life.

Why Everything Changed So Suddenly

Between 8,000 and 4,500 years ago, the transition from humid to dry conditions happened far more rapidly in some areas than could be explained by orbital precession alone, resulting in the Sahara Desert as we know it today. The speed of this transformation is what keeps scientists up at night — we’re not talking about gradual change over millennia, but dramatic shifts that happened within centuries or even decades. Geologic evidence suggests that both the onset and termination of the African Humid Period were abrupt, with both events likely occurring on a timescale of decades to centuries. After vegetation declined, the Sahara became barren and was claimed by sand, with this transition from the “green Sahara” to the present-day dry Sahara considered the greatest environmental transition of the Holocene in northern Africa.

The Human Factor in Desert Creation

Archaeologist David Wright suggests humans and their goats may have tipped the balance, with archaeological records showing that wherever pastoralists appeared with their domesticated animals, there was a corresponding change in plant types and varieties — as if every time humans and their livestock moved across grasslands, they turned everything to scrub and desert in their wake. It’s a sobering thought that our ancestors might have accidentally triggered one of the most dramatic environmental changes in human history. During the last humid period, the Sahara was filled with hunter-gatherers, but as the orbit slowly changed and less rain fell, humans would have needed to domesticate animals like cattle and goats for sustenance, potentially accelerating the degradation through overgrazing practices. This connection between human activity and environmental collapse should make us pause and think about our current impact on the planet.

The Dust That Feeds the Amazon

Saharan dust carried on the wind is a vital source of nutrients for the Amazon and the Atlantic Ocean, meaning a greener Sahara could have an even bigger global effect than current simulations suggest. This interconnectedness is absolutely mind-blowing — the same desert that seems lifeless and barren is actually feeding the world’s largest rainforest thousands of miles away. Many larger and more complex ecosystems depend on the barren desert of the Sahara, with the Amazon being fertilized by dust blown across the Atlantic, while Saharan heat drives atmospheric circulation through Atlantic winds. It’s like discovering that your seemingly useless backyard is actually the key ingredient that keeps your neighbor’s garden thriving. The delicate balance of these global systems shows just how connected everything on our planet really is.

Solar Panels Could Trigger a Green Revolution

Climate models reveal that when solar farm coverage reaches 20% of the Sahara’s area, it triggers a feedback loop where heat from darker solar panels creates temperature differences with surrounding oceans, lowering surface air pressure and causing moist air to rise and condense into raindrops, leading to increased monsoon rainfall that supports plant growth, which absorbs light better than sand and creates more evaporation and humidity. The irony is delicious — our attempt to solve climate change through renewable energy might accidentally recreate the Green Sahara. Research shows that installing large numbers of wind and solar power plants in the arid Sahara environment could increase rainfall and encourage plant growth, with both technologies capable of reducing albedo and increasing local temperature, precipitation, and vegetation. It’s like we’re playing god with the world’s largest desert, but the consequences might actually be beneficial.

The Price of Playing With Nature

Covering 20% of the Sahara with solar farms raises local temperatures by 1.5°C, while 50% coverage increases temperatures by 2.5°C, eventually spreading around the globe and raising world average temperature by 0.16°C to 0.39°C respectively, with polar regions warming more than tropics and increasing Arctic sea ice loss. The numbers might seem small, but in climate terms, they’re absolutely massive. This massive new heat source would reorganize global air and ocean circulation, affecting precipitation patterns worldwide and shifting the narrow band of heavy tropical rainfall that accounts for more than 30% of global precipitation and supports Amazon and Congo rainforests. The redistribution of rainfall in the Sahara and nearby regions would reduce precipitation in the Amazon by 10-30%, roughly the same amount of extra rainfall the Sahara would receive due to lower albedo from solar panels. We’d essentially be robbing Peter to pay Paul, but on a planetary scale.

Evidence Written in Ancient Shorelines

The spits etched into Chad’s desert were actually formed thousands of years ago along the shores of a vast lake, providing geomorphological evidence for an enhanced monsoon from paleolake Megachad. These geological signatures are like fingerprints left by ancient waters, proof that massive lakes once dominated landscapes that are now bone dry. Scientists have mapped 531,520 kilometers of paleodrainage and 11,996 individual lakes with a combined surface area of 341,277 square kilometers, covering 3.7% of the green Sahara, with some lakes being extremely large like Megalakes Chad and Timbuktu in the southern Sahara. The scale of this hydrological network is staggering — imagine trying to map every stream, river, and lake across an area larger than India, then realizing it’s all been buried under sand for thousands of years.

The Civilizations That Thrived in Paradise

When the African Humid Period ended, humans gradually abandoned the desert in favor of regions with more secure water supplies, such as the Nile Valley and Mesopotamia, where they gave rise to early complex societies. This mass migration wasn’t just a footnote in history — it was the catalyst that shaped human civilization as we know it. The rapid end of the humid period around 3,000 BCE caused an exodus of people from the drying savanna into the Nile valley, coinciding with the unification of Egypt under its first Pharaoh. The Kanem-Bornu Empire controlled the area around Lake Chad from 700-1900 AD and was considered by 14th-century historian Ibn Khaldun to be on par with the Romans, Turks, Chinese, and other great civilizations. These weren’t primitive societies struggling to survive — they were sophisticated civilizations that would have made ancient Rome jealous.

Climate Cycles That Span Millennia

Research has confirmed that the Sahara alternates between arid desert and humid savanna with lakes in a 20,000-year cycle, with humid periods recurring continuously throughout the time of human evolution. Understanding these mega-cycles puts our current climate fears into perspective — what we’re experiencing now might be just one note in a symphony that’s been playing for hundreds of thousands of years. The Sahara region has experienced periodic wet periods over the Quaternary and beyond, with these North African Humid Periods astronomically paced by precession, and recent climate modeling has simulated 20 such periods over the past 800,000 years. The middle period of this cycle shows the green phase that started 11,000 years ago and lasted about 6,000 years, while the current situation represents a return to desert conditions with eventual extreme aridity. We’re living through just one chapter of an epic environmental story that’s been unfolding since before our species even existed.

The Mediterranean Connection

Recent research reveals that moisture contributions from the Mediterranean Sea and North Atlantic Ocean during winter were as important as the expanded summer monsoon for the greening of the Sahara during the African Humid Period. This discovery completely rewrites our understanding of how the Green Sahara worked — it wasn’t just about stronger summer rains, but a complete reorganization of the entire regional climate system. Scientists propose that during the African Humid Period, the influence of winter storm tracks shifted south to reach at least 24°N and potentially 18°N. Fossil pollen data indicates that the green Sahara was composed of steppe biome north of 24°N and a mix of steppe and Sahelian biomes from 15 to 24°N, with climate simulations showing the African monsoon reaching a maximum latitude of 24°N. The complexity of these climate interactions makes you realize that turning the Sahara green again isn’t just about flipping a switch — it’s about orchestrating a delicate dance between oceans, atmosphere, and land.

Modern Technology Meets Ancient Patterns

In the future, the Sahara and Sahelian regions could experience more rainfall than today as a result of climate change, with wetter periods termed African humid periods having occurred in the past and witnessed a mesic landscape in place of today’s hyperarid environment. The twist is that our current climate crisis might accidentally recreate conditions similar to the ancient Green Sahara. Today’s rising greenhouse gases could even have their own greening effect on the Sahara, though not to the degree of orbital-forced changes, but this idea remains uncertain due to climate model limitations. Meanwhile, massive solar and wind farms could increase rainfall in the Sahara and the Sahel through creating positive feedback loops where increased precipitation leads to vegetation growth, though this undertaking has yet to be tested and humans might have to wait until the year 12,000 or longer to see whether the Sahara will naturally turn green again. We’re essentially racing against a 23,000-year cosmic clock, trying to use technology to recreate what nature has done repeatedly throughout Earth’s history.

The $500 Trillion Question

According to calculations, solar panels covering just 1.2% of the Sahara Desert — around 110,000 square kilometers — would be enough to satisfy the entire world’s energy needs. The numbers sound almost too good to be true, like discovering you could power your entire neighborhood with the energy from your garden shed. It would take 51.4 billion 350-watt solar panels covering 115,625 square miles to power the entire world, but the estimated cost would be $514 trillion — about 23 times the cost of the entire US economy. If just 2-3% of the Sahara area were covered with solar panels, the installation could generate more than 25 terawatts of electrical energy, produce freshwater, and potentially transform the Sahara into a paradise while stopping migration from Africa to Europe. The economics are staggering, but so is the potential payoff — we’re talking about simultaneously solving the global energy crisis and potentially recreating one of the most dramatic environmental transformations in Earth’s recent history.

Dust, Sand, and the Harsh Reality

Dust from North Africa reduces photovoltaic power output by scattering sunlight, absorbing irradiance, and promoting cloud formation, with field data from 46 dust events between 2019 and 2023 highlighting the difficulty of predicting solar panel performance, while long-term impacts include contamination and erosion that further reduce efficiency and increase maintenance costs. The romantic vision of endless solar panels quickly meets the harsh reality of desert conditions.