Picture a killer so small it could sit comfortably on your fingernail, yet so devastating it could eliminate an entire species spanning 16 different varieties across North America. This isn’t science fiction—it’s the emerald ash borer’s reality. While you’re reading this, millions of ash trees are dying silently in forests and neighborhoods from coast to coast, victim to an invasion that started with a single cargo shipment decades ago.

The Green Menace That Arrived by Accident

The emerald ash borer was first discovered in southeastern Michigan near Detroit in the summer of 2002, though it probably arrived in the United States on solid wood packing material carried in cargo ships or airplanes originating in its native Asia. This metallic green beetle, measuring just half an inch long, might look like a piece of living jewelry, but don’t let its beauty fool you. The emerald ash borer is the most destructive and costly forest insect to ever have invaded North America. What makes this invasion particularly insidious is how long it went undetected. The beetle has probably been here for many years before scientists finally spotted it. Imagine if a thief broke into your house and spent years slowly stealing everything valuable, but so quietly that you never noticed until the rooms were almost empty.

An Army of Eight Billion Trees Under Siege

All of North America’s more than 8 billion ash trees are at risk from the emerald ash borer. White ash is an important component of hardwood forests throughout the East, and green ash and black ash are very important wetland and riparian trees. These trees aren’t just numbers on a forestry report—they’re the backbone of entire ecosystems. The loss of ash in floodplain shelterbelts will reduce crop protection, and riparian corridors will be impacted as large gaps due to the loss of green ash allow increased light to alter the quality of these areas. Think of ash trees as the supporting columns in nature’s cathedral. When they fall, everything else starts to crumble too. In many areas ash trees dominate forested wetlands, and outbreaks of EAB can completely remove the forest cover.

The Beetle’s Deadly Life Cycle

The emerald ash borer undergoes a complete metamorphosis, starting as an egg, becoming a larva, changing to become a pupa and then an adult, with the life cycle taking either 1 or 2 years to complete. Adults begin emerging from within ash trees around the middle of June, with emergence continuing for about 5 weeks, and the female starts laying her eggs on the bark of ash trees about 2 weeks after she emerges. After 7 to 10 days, the eggs hatch and the larvae move into the bark, to begin feeding on the phloem (inner bark) and cambium of the tree. This is where the real damage begins. The larvae tunnel through the wood just under the bark and damage the tree’s ability to transport nutrients and water. It’s like someone cutting your circulatory system—no matter how strong you are, you can’t survive when your lifeline is severed.

The Silent Symptoms of a Dying Tree

The emerald ash borer’s presence typically goes undetected until trees show symptoms of being infested. Canopy dieback starts from the top down, with thinning of the crown occurring until the tree is bare and heavily infested. Epicormic shoots—sprouts that grow from the roots and trunk—appear, with leaves that are often larger than normal. Woodpecker damage during the winter is often the first sign that an ash tree is infested, as the birds remove pieces of bark while feeding on EAB larvae inside the tree. When adult beetles emerge from the tree, they leave distinctive D-shaped (half-moon shaped) exit holes in the outer bark of branches and the trunk. These holes are like tiny tombstones marking where another generation of killers was born.

The Staggering Economic Catastrophe

The numbers are almost too large to comprehend. In a study conducted in 2011, researchers estimated it would cost between $13.4 and $26 billion to remove and replace ash trees growing in parks, private land, and along streets in communities in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin alone. In 2010 it was estimated that the treatment, removal, and replacement of ash trees would cost 10.7 billion dollars. But these figures only tell part of the story. It is estimated that there was an average drop of 1% in wage earnings following EAB detection for a total loss of 11.8 billion in US labor earnings over 10 years. The municipal forest budget doubled during the peak years of the EAB invasion, 5-8 years after confirmation per state, and the budget nearly tripled around year eight. Imagine if every homeowner in your neighborhood suddenly had to pay thousands of dollars to remove dying trees—that’s the reality many communities are facing.

Urban Trees Bear the Heaviest Burden

Because ash is widely planted as a street tree, the greatest economic impacts of EAB have been, and will be, felt in cities. There are an estimated 56.1 million green and white ash trees in rural and urban landscapes, with most occurring along rural riparian areas, but the 1.5 million ash trees that occur in towns and cities will cost much more in removal, stump grinding, and replacement. The economic impact of removing thousands of street and yard trees will need to occur not just for mitigation, but also because the dead trees pose a hazard and liability. Infested trees in cities and near structures are usually removed because they pose a danger to people and property. Walking down a tree-lined street is one of life’s simple pleasures, but imagine those same streets barren and treeless—that’s what many communities are experiencing.

The Cultural Devastation Beyond Economics

For Native American communities, the loss goes far deeper than economics. Native American tribes use ash, especially black ash, to make baskets because the wood splits easily into thin strips along the growth rings, and black ash is an important part of the history, culture and tradition of numerous eastern and Midwestern tribes. Ash wood has many specialized uses, including as the principal wood used in baseball bats. These aren’t just trees dying—entire traditions and ways of life are disappearing. It’s like losing the main ingredient for your grandmother’s secret recipe, except the recipe represents centuries of cultural knowledge passed down through generations.

The Beetle’s Relentless March Across America

As of February 2025, the emerald ash borer is now found in 37 states and 6 Canadian provinces. Ash trees infested with emerald ash borer beetles were discovered in Marion County in August 2024. Unfortunately, this is potentially the heaviest infestation of emerald ash borer in Oregon. The beetle’s spread isn’t random—it follows human transportation routes. EAB and many other harmful invasive pests hitchhike on firewood, so it’s important to collect or buy firewood as close as possible to where you plan to use it. Every time someone moves infested wood, they’re essentially giving the beetle a free ride to new hunting grounds.

The Devastating Speed of Tree Death

Depending on the vigor of the tree, an infested tree can die from the top down within 4 years. Ash trees die only three to five years after infestation. The invasive pest is currently the most damaging threat to trees in Wisconsin, killing more than 99% of the ash trees it infests. Nearly 100% of ash trees infested with EAB have been killed. This isn’t a slow decline over decades—it’s a rapid ecological collapse. A tree like this can produce easily 100 to 150 emerald ash borers in a year. Each dying tree becomes a factory for producing more killers, spreading the destruction exponentially.

The Battle Against an Invisible Enemy

State workers created trap trees by girdling them, and as those trees slowly die, they send out a distress signal that attracts any beetles nearby, then the girdled trap trees were removed, and workers peeled back the bark to see how many beetle larvae they could find. The larvae eat through the wood under the tree bark, leaving squiggly lines and sawdust in their wake. Larval feeding creates serpentine (S-shaped) galleries that weave across the woodgrain. Detecting the emerald ash borer is like trying to find a needle in a haystack, except the needle is smaller than your pinky nail and is hidden inside a tree. Tiny but destructive, the emerald ash borer is an invasive beetle that has killed millions of ash trees across North America, and in some cases, infested regions have lost nearly 100% of their ash trees to this pest.

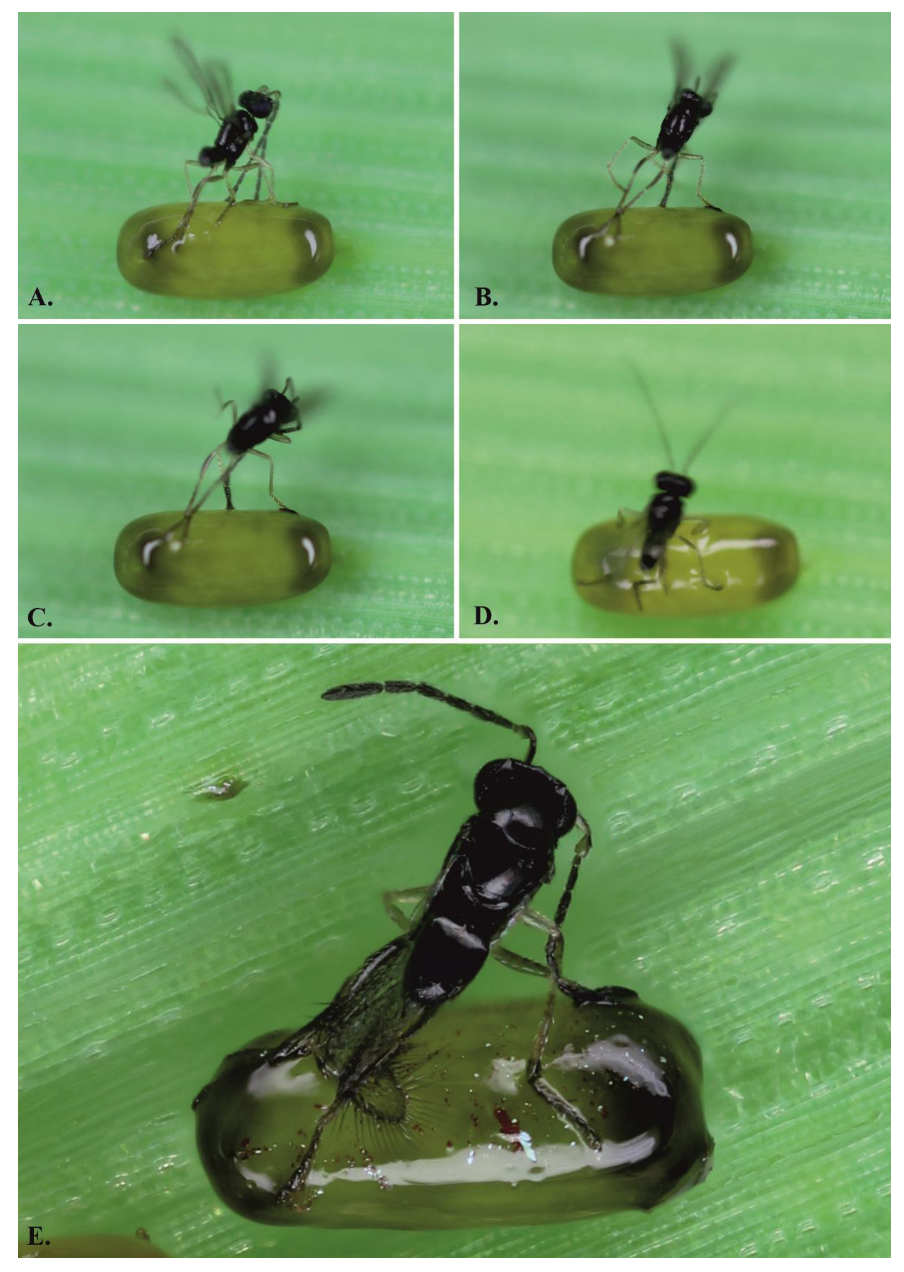

Nature’s Counterattack: The Parasitoid Warriors

Because of the enormous ecological and economic impact posed by EAB to North American ash trees, scientists searched for additional parasitoid species from the native range of EAB in Asia to release in North America, with the goal of increasing the number of EAB eggs and larvae killed by parasitoid wasps and hopefully slow the rate at which ash trees were killed by EAB. Since 2007, four species of non-native parasitoid wasp species from Asia have been introduced into North America. Four species of wasps have been released for EAB biological control in the United States: Oobius agrili lays its eggs inside the eggs of EAB, while the other three wasp species attack EAB larvae under the bark of ash trees, with Spathius agrili and Spathius galinae paralyzing EAB larvae and laying their eggs on the outside of the EAB larvae, and Tetrastichus planipennisi laying its eggs inside of EAB larvae. These tiny warriors are like nature’s special forces, trained specifically to hunt down the emerald ash borer.

The Promise and Challenges of Biological Control

Research in three northeastern states in the U.S. found wild populations of Spathius galinae established two years after release, with parasitization rates of emerald ash borers as high as 49 percent. Of the four parasitoid species, Spathius galinae currently shows the greatest potential for biocontrol. These rates are lower than those in S. galinae’s native Russia, where the wasp parasitizes about 62 percent of late-instar EAB larvae, but the strong results just two years after principal release are promising, as natural enemy introduction normally takes more time for the introduced agent to firmly establish. However, success isn’t guaranteed everywhere. While these released parasitoid wasps have successfully established in the northern United States, establishment of the wasps has been difficult in North Carolina, possibly due to a mismatch between the timing of wasp releases and the timing of the EAB life cycle in the warmer climate.

Climate Change Complicates the Fight

Sudden cold waves may be lethal to overwintering larvae of two parasitoid wasp species used for biological control of emerald ash borer, while the borer larvae appear to more easily weather the extreme cold. Arctic cold at a study site in southern Michigan during 2019 killed up to half of S. galinae larvae, and 30 percent of T. planipennisi, though those at the other site in central Connecticut made it through the winter relatively unscathed. The very rapid cycling between warm and cold events in response to global climate change may lead to higher winter mortality of the wasp larvae, despite the general warming of mean winter temperatures associated with global climate change. It’s a cruel irony that climate change, which may make some regions more hospitable to the emerald ash borer, simultaneously makes it harder for our biological weapons to survive.

Woodpeckers: Nature’s First Responders

Native woodpeckers are the primary predators of emerald ash borer in North America and are one of the most important sources of EAB biological control. In Michigan and Ohio, the downy woodpecker, the hairy woodpecker, and the red-bellied woodpecker have all been observed to feed on EAB larvae, generally ignoring small young EAB larvae during most of the summer, but becoming voracious predators of large EAB larvae, with woodpecker predation beginning in the fall and continuing through the winter until the following spring. In declining and healthy overstory ash, woodpeckers killed 38.5% and 13.2% of larvae, respectively. Although woodpeckers and native parasitoids kill some EAB larvae, they have not been able to suppress EAB populations to prevent trees from dying. These feathered warriors are giving their all, but they’re fighting a losing battle without reinforcements.

The Race to Save Genetic Treasures

Gathering seeds from healthy ash trees is one thing people are doing in the face of this invasion—just in case any of those trees prove to have natural resistance to the emerald ash borer. Broader-scale responses to the EAB infestation focus on breeding resistant ash trees and developing biological control agents. Scientists are essentially creating a genetic Noah’s ark, preserving the DNA of ash trees before they disappear forever. There are high numbers of ash seedlings, but it is unlikely that EAB will allow any of these seedlings to reach maturity, and it is possible that ash in wetland areas could go the way of the American chestnut: seedlings grow into saplings or young trees that are large enough to be appetizing to EAB, they die, then the cycle repeats, with individuals rarely reaching canopy height or producing viable seeds. The American chestnut was once called the “redwood of the East” until a blight wiped out billions of trees. Are we watching history repeat itself with ash?

Individual Action in the Face of Overwhelming Odds

One way everyone can help is by checking ash trees for signs of beetle damage such as D-shaped holes in the bark or dead branches at the top of the tree that aren’t producing leaves. You should identify susceptible trees in your yard and monitor them for signs of EAB, and if you suspect an EAB infestation, report it to your local county agricultural commissioner or to CDFA. Individual trees can be treated to kill EAB if the infestation is caught early enough, with the most common treatment being systemic application of the insecticide emamectin benzoate, which needs to be re-applied every few years to keep the insect at bay.