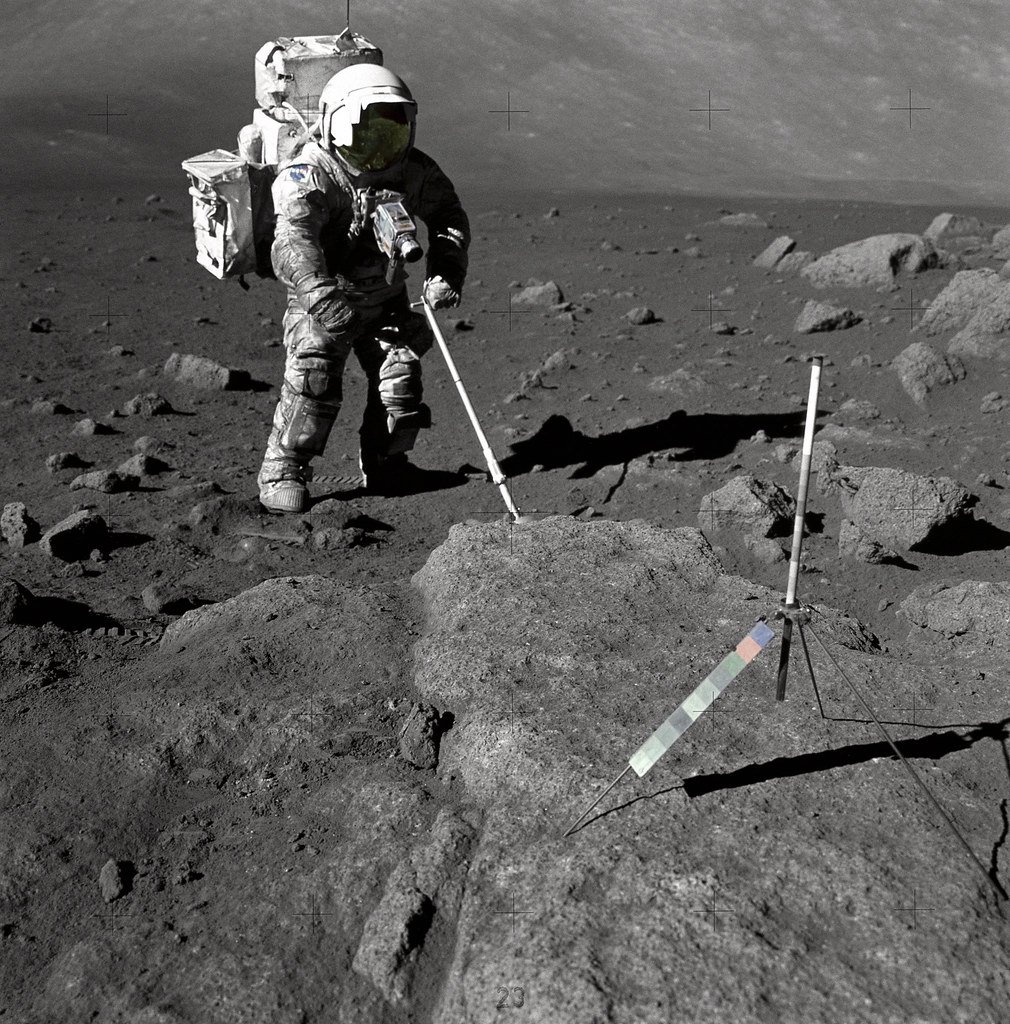

Picture this: you’ve just spent hours walking on the surface of the Moon, bouncing around in a bulky spacesuit, collecting rocks and conducting experiments. When you finally return to your lunar module and remove your helmet, you’re hit with something completely unexpected. The Moon smells like gunpowder. Not just a faint whiff, but a strong, unmistakable odor that immediately brings to mind the aftermath of fireworks or target practice. This isn’t science fiction — it’s exactly what happened to every single Apollo astronaut who walked on the lunar surface.

The Universal Apollo Experience

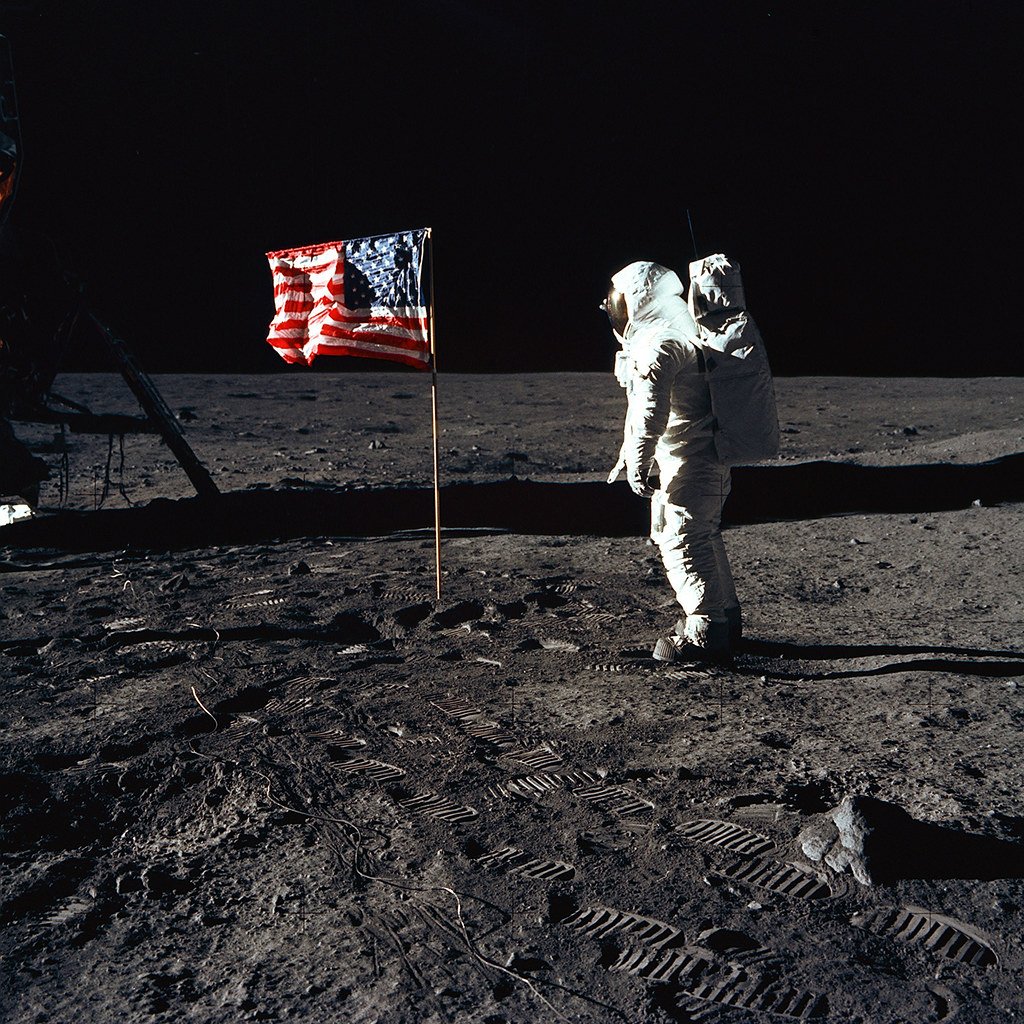

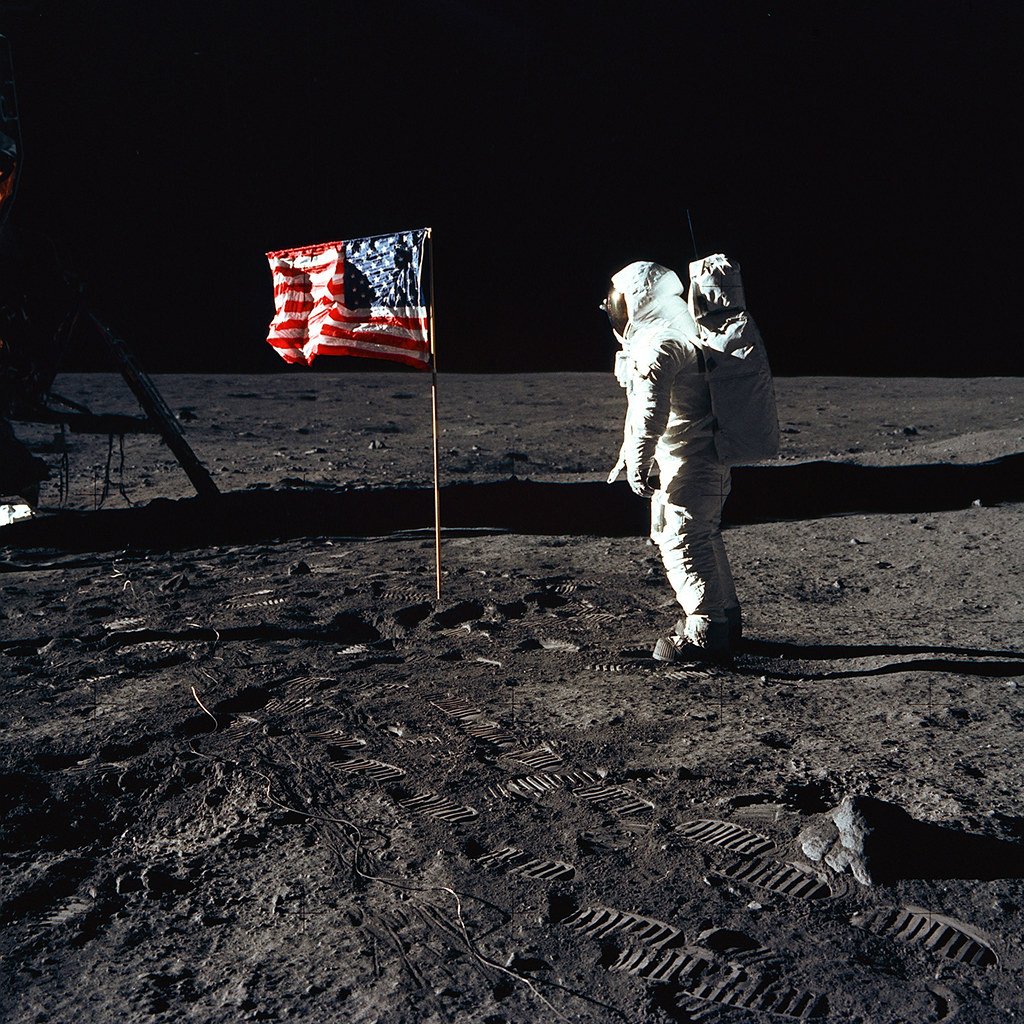

Twelve people have walked on the Moon and all of them agree: the Moon smells like gunpowder. This wasn’t just one astronaut’s imagination or a strange coincidence. From the first moonwalk of Apollo 11 to the final mission of Apollo 17, every lunar explorer reported the same distinctive scent. According to Space.com, astronaut Jack Schmitt said: “All I can say is that everyone’s instant impression of the smell was that of spent gunpowder, not that it was ‘metallic’ or ‘acrid’. Spent gunpowder smell probably was much more implanted in our memories than other comparable odors.” The consistency of this observation across different missions, crews, and timeframes makes it one of the most intriguing mysteries of lunar exploration. What’s even more fascinating is that these trained professionals, many with military backgrounds, immediately recognized the smell and could describe it with such precision.

Charlie Duke’s Radio Report

Duke: Houston, the lunar dust smells like gunpowder. [Pause] England: We copy that, Charlie. Duke: Really, really a strong odor to it. This exchange between Apollo 16’s Charlie Duke and mission control perfectly captures the surprise and intensity of the experience. Duke wasn’t just making casual conversation — he felt compelled to report this unexpected discovery to ground control immediately. “It is really a strong smell,” Apollo 16 pilot Charlie Duke radioed to Houston. “It has that taste — to me, [of] gunpowder — and the smell of gunpowder, too.” Apollo 17 astronaut Gene Cernan said, “smells like someone just fired a carbine in here.” The fact that multiple astronauts not only smelled it but also tasted it (lunar dust inevitably gets everywhere in the confined space of a lunar module) adds another layer to this mystery. These weren’t subtle sensations but powerful, immediate impressions that couldn’t be ignored.

Buzz Aldrin’s Detailed Description

Aldrin also noted yet another lunar dust episode on the Apollo 11 mission. “It was like burnt charcoal,” Aldrin said, “or similar to the ashes that are in a fireplace, especially if you sprinkle a little water on them.” Buzz Aldrin, the second person to walk on the Moon, provided even more colorful descriptions of the lunar aroma. In his 2009 book “Magnificent Desolation: The Long Journey Home from the Moon,” Aldrin, the second man to ever walk the lunar surface, recalled that when he and fellow pioneering astronaut Neil Armstrong got back into their lander and realized they were covered in lunar dust, they were met with “a pungent metallic smell, something like gunpowder, or the smell in the air after a firecracker has gone off.” In a 2015 Space.com interview, Aldrin expounded on his description of the Moon’s aroma, describing it as smelling “like burnt charcoal, or similar to the ashes that are in a fireplace, especially if you sprinkle a little water on them.” His comparison to fireplace ashes is particularly interesting because it suggests the smell had earthy, combustion-related qualities that went beyond simple metallic or chemical odors.

How They Actually Smelled It

No astronaut walking on the Moon’s surface has ever removed their helmet and taken a whiff. Instead, the smell of the Moon lingers in the dust on their suit and on the rocks brought back to the ship. You might wonder how astronauts could smell anything while wearing pressurized suits with their own air supply. The answer lies in what happened after their moonwalks. Now, obviously these astronauts weren’t taking their helmets off and taking a big whiff of the non-existent lunar atmosphere; that’s a way to a nasty death. They were safely back in the lunar module and just sniffing the air. For all their care in collecting specimens, the lunar dust had clung to their suits; and, shaken loose once returned to the craft, it was free to float around the module and get in everyone’s noses. From the modest 2.5 hour “moonwalk” of Apollo 11 to the forays totaling just over 22 hours outside a spacecraft on Apollo 17, NASA’s Apollo landing crews could not escape tracking lunar material inside their moon lander homes. The dust was incredibly clingy and pervasive, making its way into every crevice of their equipment and living space.

The Sticky, Invasive Nature of Moon Dust

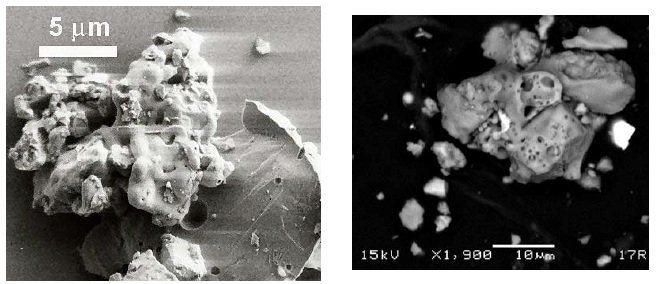

It clung so severely to the moonwalking space suits, that even brushing each other off before returning to the module effectively did nothing to remove the dust. Considering that the astronauts were notoriously clumsy on the lunar surface, trying to adapt to both the unwieldy suits and the lowered gravity, most of them had taken several tumbles over the course of their moonwalks, and these suits were no longer pristine after many hours on the surface. They were, instead, rather comprehensively covered in lunar dirt. Moon dust isn’t like Earth dust at all. It was more than just getting wedged in the folds of the suit—it was static cling. The astronauts discovered that lunar dust has an almost supernatural ability to stick to everything it touches. This is because lunar dust is more chemically reactive and has larger surface areas composed of sharper jagged edges than Earth dust. Without wind, water, or weathering processes to smooth out the particles over millions of years, each grain of lunar dust maintains its sharp, angular edges, making it incredibly abrasive and clingy. The result was that astronauts became walking dust magnets, carrying the lunar surface back into their spacecraft whether they wanted to or not.

The Chemical Composition Mystery

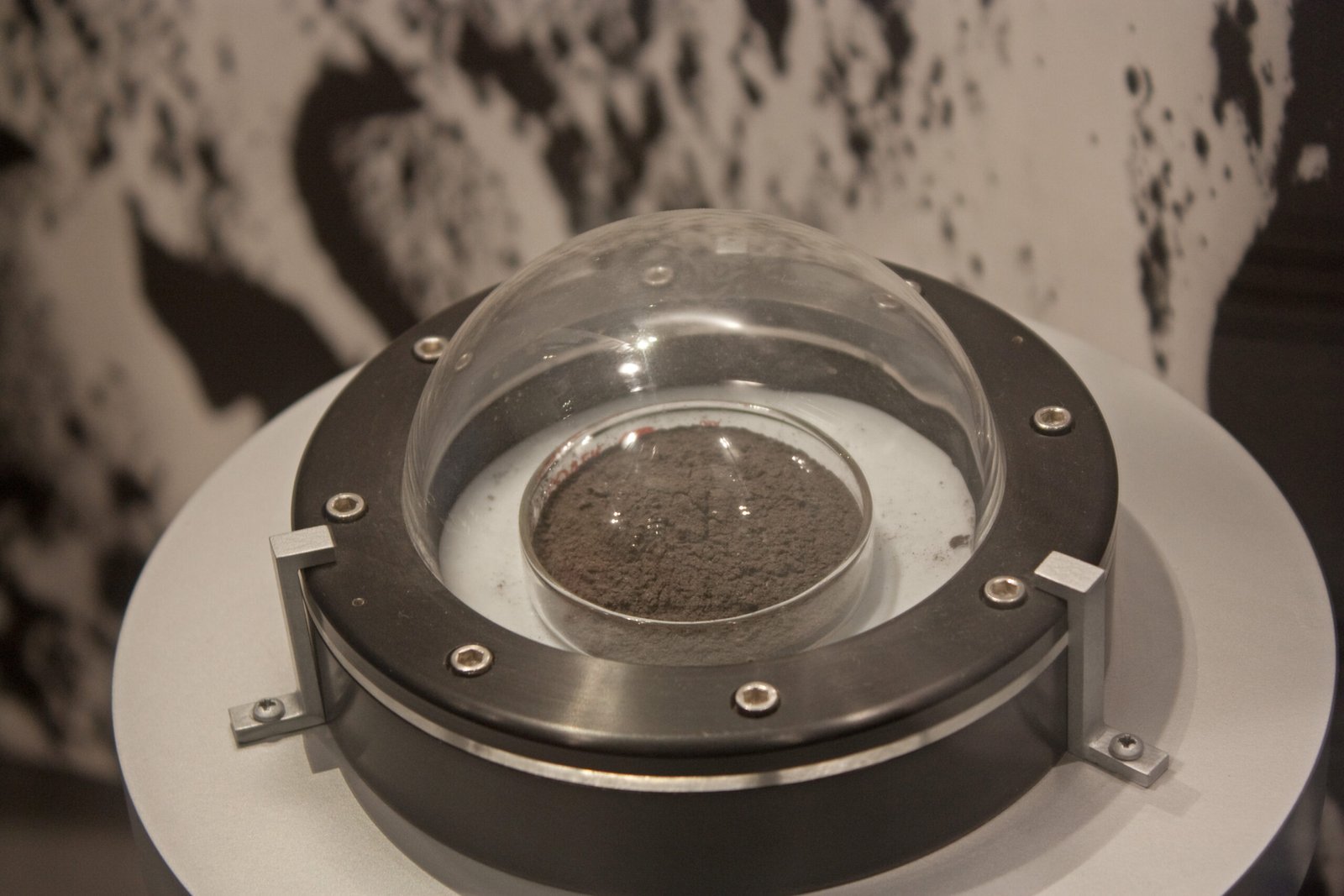

This is interesting because the makeup of lunar dirt is completely different to that of gunpowder. Moon dust is made up of silicon dioxide glass (created by meteoroids hitting the moon), as well as iron, calcium and magnesium contained in minerals such as olivine and pyroxene. Modern gunpowder, on the other hand, is a combination of nitrocellulose and nitro-glycerine. Here’s where the mystery deepens significantly. Major chemical elements in the upper lunar crust: O, Si, Al, Ca, Fe, Mg, Ti. The moon is depleted in water and volatile elements such as Na and K, which are only found in very small quantities. The Moon’s surface is primarily composed of materials that have absolutely nothing in common with gunpowder. The original formula for gunpowder was charcoal, sulfur, and nitrate. Modern gunpowders also contain carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen. However, these elements aren’t found in substantial amounts in lunar rocks or dust. This chemical disconnect makes the smell phenomenon even more puzzling and has led scientists to propose several competing theories about what’s really happening.

The Desert Rain Effect Theory

One put forward by astronaut Don Pettit is the ‘desert-rain’ effect. ‘The moon is like a 4 billion year old desert … when moon dust comes in contact with moist air in a lunar module, you get the ‘desert-rain effect’ (where molecules that have been trapped in dry soil are released), producing smells previously hidden. Think about stepping outside after the first rain following a long, dry summer. That distinctive petrichor smell comes from volatile compounds that have been trapped in dry soil suddenly being released when moisture arrives. Astronaut Don Pettit suggests something similar might be happening with lunar dust. There are several theories, including: Moon dust reacting with moist air in the lunar module and the moisture releasing volatile smelly molecules into the air. The Moon has been bone dry for billions of years, with any volatile compounds locked away in the crystal structure of dust particles. When this ancient, desiccated material suddenly encounters the humid, oxygen-rich atmosphere of the lunar module, it might release a burst of trapped molecules that create the gunpowder-like smell.

The Oxidation Theory

Similar to astronauts who report a ‘burnt metal’ smell when they return from a space-walk, it may be that moon dust undergoes oxidation when exposed to oxygen within the lunar lander. Oxidation is similar to burning but produces no smoke or flames—though it may account for the smell. Another compelling explanation focuses on what happens when lunar dust meets oxygen for the first time in eons. On Earth, iron and other metals naturally form oxide layers when exposed to our oxygen-rich atmosphere. But on the Moon, with no atmosphere to speak of, metals remain in their pure, highly reactive state. Since there’s no chemical similarity between moondust and gunpowder, the smell could have been the dust reacting with oxygen and/or water inside the lander, or due to the release of charged particles from the Sun that had become trapped in the dust. When this reactive lunar material suddenly encounters oxygen inside the lunar module, it might undergo rapid oxidation reactions that produce the distinctive smell. It’s like watching metal rust in fast-forward, creating odors reminiscent of metallic combustion.

The Solar Wind Ion Theory

Solar wind ions getting caught in the dust and evaporating when in contact with air inside the spacecraft. The Moon’s surface is constantly bombarded by the solar wind — a stream of charged particles flowing from the Sun. On the daylit side of the Moon, solar hard ultraviolet and X-ray radiation is energetic enough to knock electrons out of atoms and molecules in the lunar regolith. Positive charges build up until the tiniest particles of lunar dust (measuring 1 micrometre and smaller) are repelled from the surface and lofted anywhere from metres to kilometres high. Without an atmosphere or magnetic field to protect it, lunar dust becomes a repository for these high-energy particles over millions of years. When the entire subject of the dust smell came up several years ago, I put forth that what the astronauts were smelling, that is, what their mucus membrane sensed, was highly activated dust particles with ‘dangling bonds,’ Taylor said. When this ion-saturated dust encounters the air inside the lunar module, these trapped particles might be released in a burst of energy that creates the gunpowder smell.

The Dangling Bonds Hypothesis

In a nut-shell, I believe that the astronauts all smelled unsatisfied dangling bonds on the lunar dust … which were readily satisfied in a second by the lunar module atmosphere, or nose membrane moisture, Taylor told Space.com. Larry Taylor, who worked as a back-room advisor during the Apollo missions, proposed one of the most scientifically sophisticated explanations. In chemistry, dangling bonds are like molecular hands reaching out, desperately seeking something to grab onto. Lunar regolith is primarily the result of mechanical weathering. Continual meteoric impacts and bombardment by solar and interstellar charged atomic particles of the lunar surface over billions of years ground the basaltic and anorthositic rock, the regolith of the Moon, into progressively finer material. This violent, continuous grinding process creates countless broken molecular bonds at the surface of each dust particle. On Earth, these bonds would quickly react with oxygen, water, or other atmospheric components. But in the vacuum of space, they remain perpetually unsatisfied, creating highly reactive surfaces that might produce distinctive odors when they finally encounter the moisture and gases inside a lunar module.

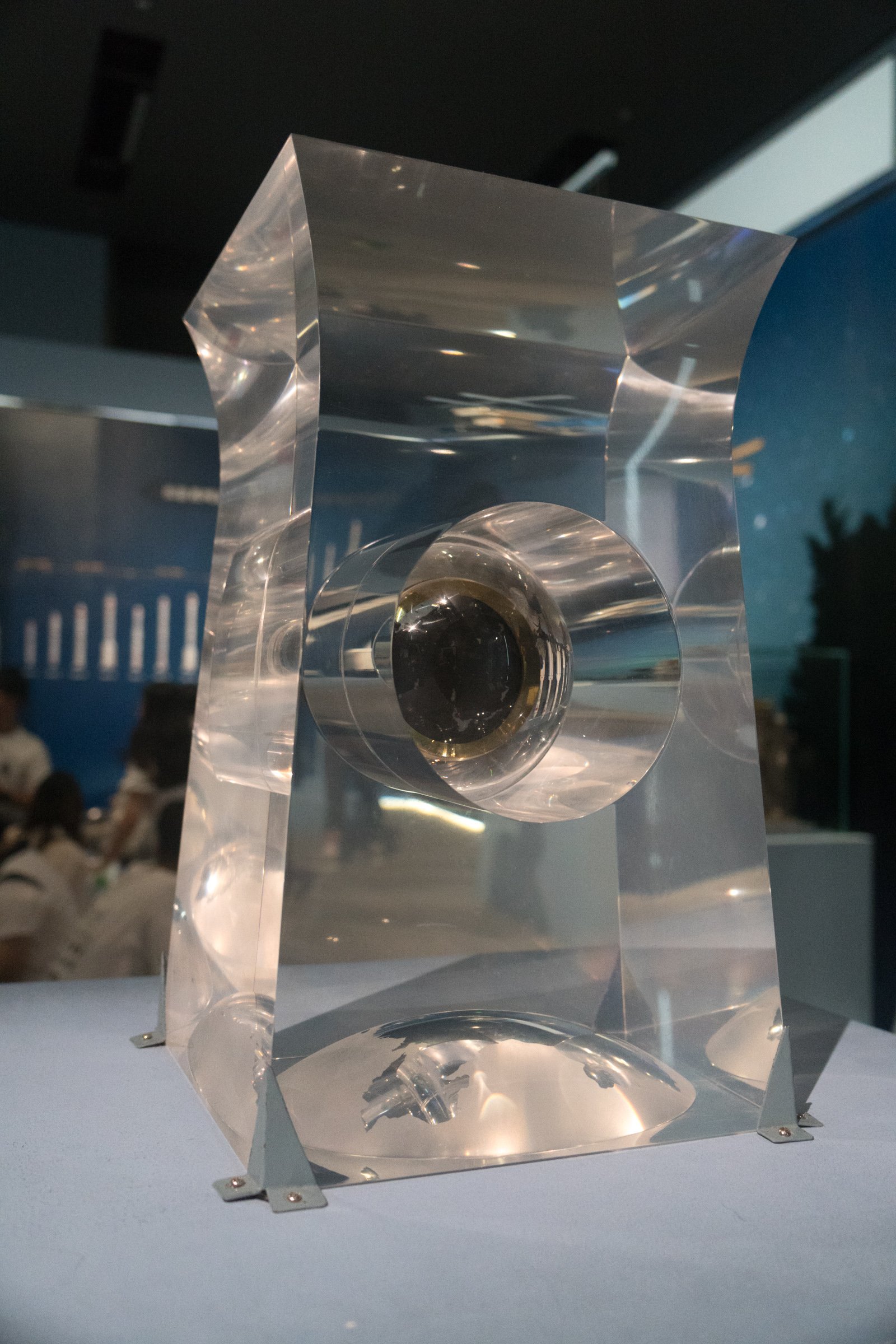

Why Earth Samples Don’t Smell

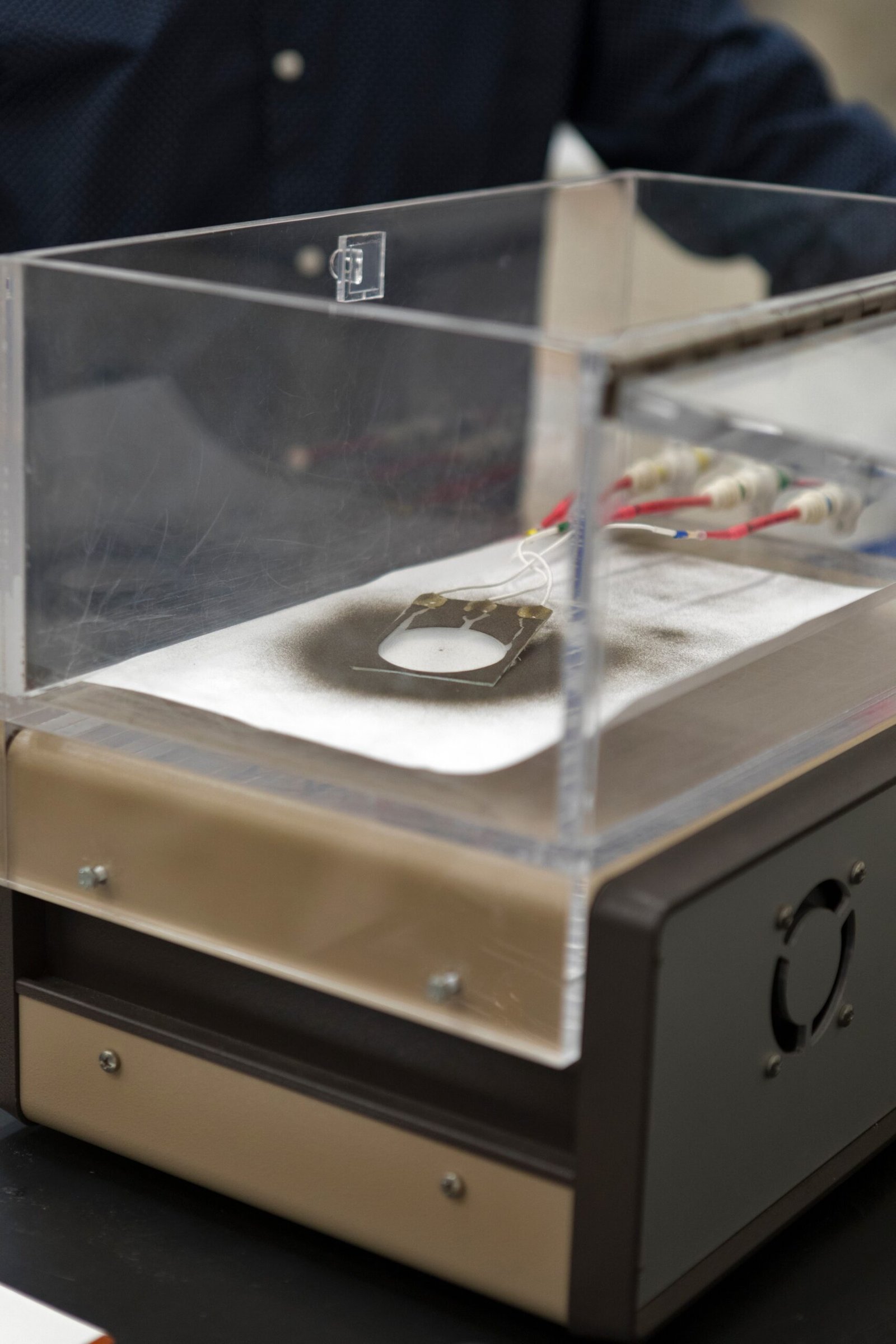

Interestingly, moon dust that has made the journey back to Earth has no smell. Here’s the smoking gun that supports many of these theories: Oddly enough, scientists back on earth who analyzed lunar samples could not detect any such odor. It is theorized that a chemical reaction due to the moist oxygen-rich enforcement of the Lunar Lander likely caused the smell, and, once that took place, there would no longer be any odor here on Earth. Every sample brought back from the Moon has been contaminated by Earth’s air and humidity. The dust has acquired a patina of rust, and due to bonding with terrestrial water and oxygen molecules, its chemical reactivity is gone. The chemical and electrostatic properties of the dirt no longer match what future astronauts will encounter on the Moon. This explains why researchers on Earth, working with the same lunar samples, never experienced the gunpowder smell. By the time the dust reached Earth’s laboratories, it had already undergone the chemical reactions that would have produced the distinctive odor during the Apollo missions.

The Space Weathering Connection

The major processes involved in the formation of lunar regolith are: Comminution: mechanical breaking of rocks and minerals into smaller particles by meteorite and micrometeorite impacts; Agglutination: welding of mineral and rock fragments together by micrometeorite-impact-produced glass; Solar wind sputtering and cosmic ray spallation caused by impacts of ions and high energy particles. These processes continue to change the physical and optical properties of the dirt over time, and it is known as space weathering. Understanding why the Moon smells like gunpowder requires understanding space weathering — the slow, relentless process that shapes every grain of lunar dust. This regolith has formed over the last 4.6 billion years from the impact of large and small meteoroids, from the steady bombardment of micrometeoroids and from solar and galactic charged particles breaking down surface rocks. Unlike Earth, where wind and water gradually smooth and oxidize particles, the Moon’s surface experiences a completely different kind of weathering. The impact of micrometeoroids, sometimes travelling faster than 96,000 km/h (60,000 mph), generates enough heat to melt or partially vaporize dust particles. This melting and refreezing welds particles together into glassy, jagged-edged agglutinates, reminiscent of tektites found on Earth. This creates a surface material unlike anything found naturally on our planet — and that uniqueness might be the key to understanding its distinctive smell.

The Health Hazard Hidden in the Scent

Schmitt wound up being a little allergic to it. Ground Control teased him about sounding congested: Allen: Sounds like you’ve got hay fever sensors, as far as that dust goes. Schmitt: It’s come on pretty fast just since I came back. I think as soon as the cabin filters most of this out that is in the air, I’ll be alright. The gunpowder smell wasn’t just a curiosity — it came with real health consequences. Apollo 17’s Jack Schmitt developed what appeared to be an allergic reaction to the lunar dust, experiencing nasal congestion and other symptoms. Based on studies of dust found on Earth, it is expected that exposure to lunar dust will result in greater risks to health both from acute and chronic exposure. This is because lunar dust is more chemically reactive and has larger surface areas composed of sharper jagged edges than Earth dust. If the chemically reactive particles are deposited in the lungs, they may cause respiratory disease. Long-term exposure to the dust may cause a more serious respiratory disease similar to silicosis. According to NASA pathologist Russell Kerschmann, prolonged exposure to Moon dust could seriously damage human lungs. This makes the mystery smell not just scientifically interesting but also a potential warning sign of a serious health hazard for future lunar explorers.

The Magnetic Properties and Static Cling

It is magnetic- Since tiny particles of iron are present in the glass outer layer of each lunar dust particle, magnets can be utilized to filter the dust out of the air and sensitive equipment. One of the strangest properties of lunar dust that might contribute to its smell is its magnetic behavior. The same space weathering processes that create the distinctive odor also produce tiny iron particles embedded in glass shells around each dust grain. It has been amply demonstrated that the outer 60–200 nm of the rims of most lunar soil grains contain a myriad of minute (typically, <10 nm) metallic Fe grains dispersed in an amorphous glassy matrix. This metallic Fe has been variously called single-domain, nano-phase, superparamagnetic, and submicroscopic Fe0, all emphatic of the small size of these gr