What if I told you that beneath the volcanic landscape of Rotorua, hidden in rock shelters and cave walls, lies some of New Zealand’s oldest art galleries? These aren’t museums filled with framed paintings—they’re ancient limestone sanctuaries where Māori ancestors painted their stories directly onto the walls using pigments born from volcanic fire. Every red mark, every black figure, every mysterious symbol tells a tale that bridges the gap between science and spirit, between geology and genealogy.

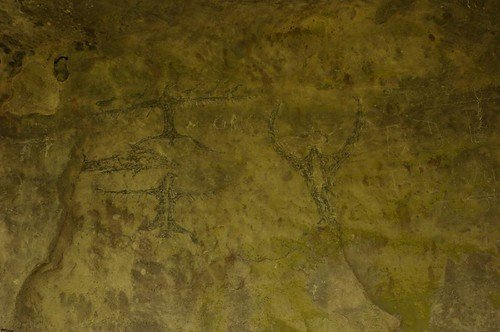

The Hidden Canvas of Lake Tarawera

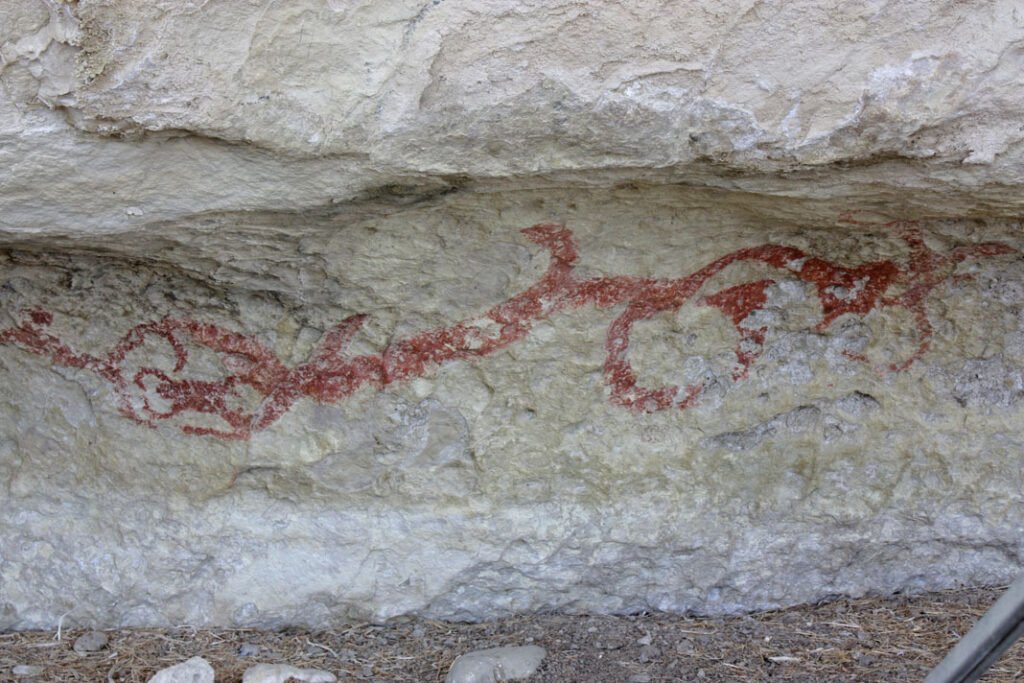

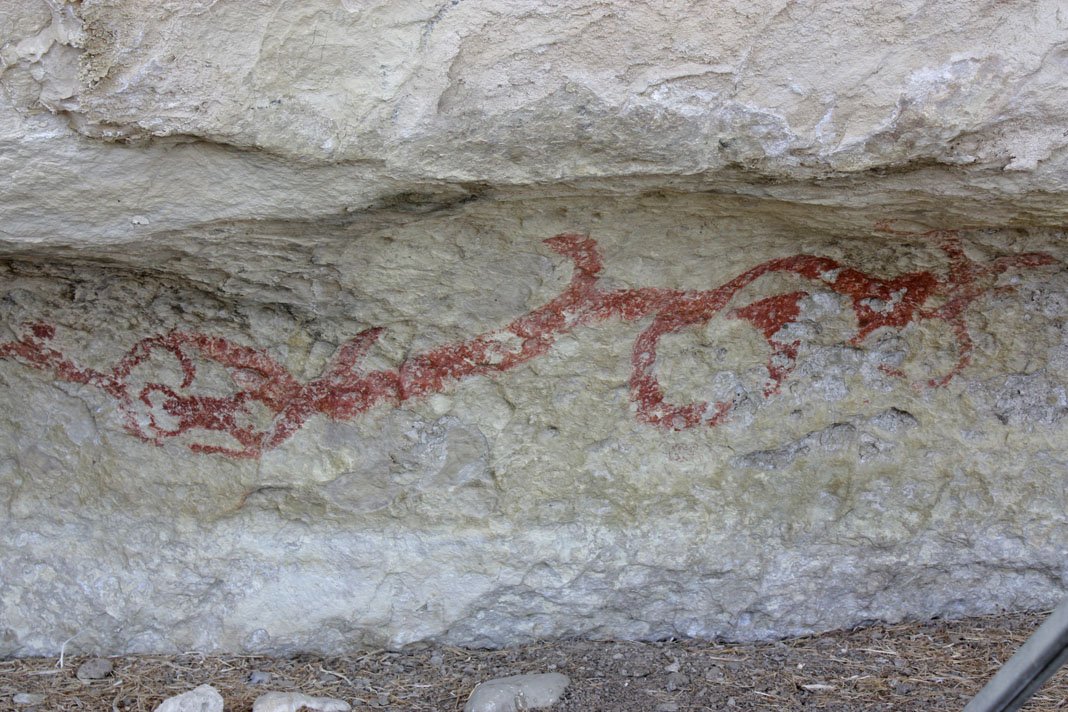

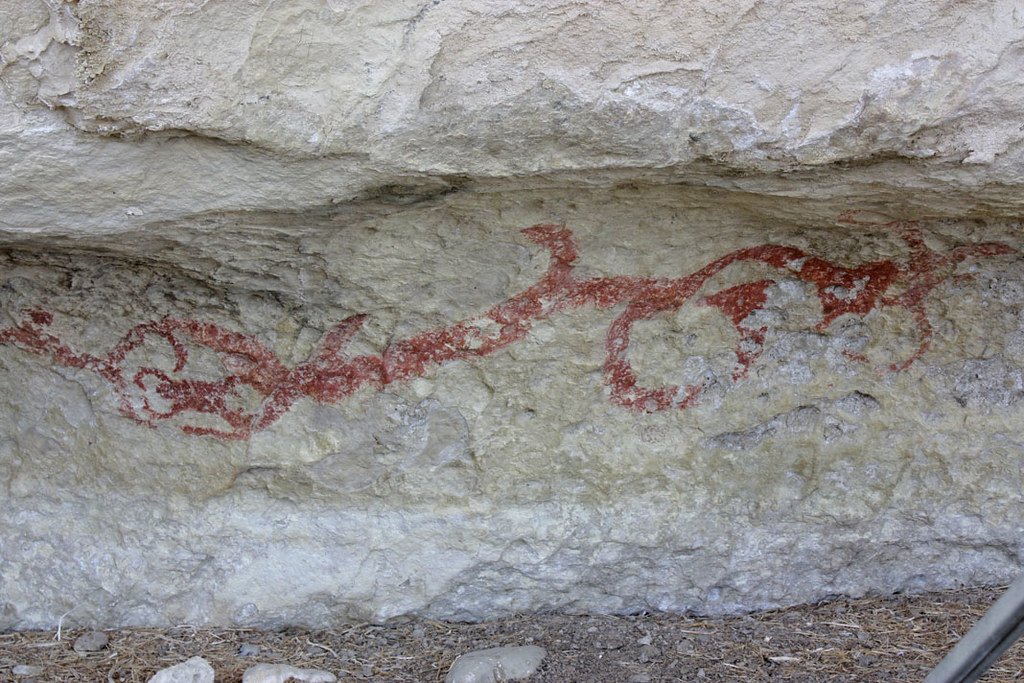

Waka designs in carvings or red ochre appear at sites on the shores of Lake Tarawera and on shelter walls from the Rotorua district through to Kāingaroa, with the best known being the vivid armada drawn in red on the edge of Lake Tarawera. Picture this: an entire fleet of war canoes painted in brilliant red ochre, stretching across rock walls like a frozen moment in time. This dramatic depiction of waka, buried under ash from the Mt Tarawera eruption of 1886, was excavated in 1962 by the Historic Places Trust. These aren’t just random doodles—they’re historical records, battle plans, or perhaps even prophecies etched in stone. Such images, says Te Kenehi Teira from the Trust, clearly tell a story. A whole armada of waka going across the lake is associated with either battle or an eruption. The lake that once reflected these ancient vessels would later witness one of New Zealand’s most devastating volcanic eruptions, as if the paintings themselves were warning of things to come.

The Science Behind Sacred Red: Kokowai and Volcanic Origins

Here’s where geology meets spirituality in the most fascinating way. Kōkōwai is generally found in areas of volcanic activity, and found either as seams of volcanic rock or deposits of hematite (or other iron oxides), and either in powdered form or baked then ground into a powder, kokowai was long associated with concepts of mana, tapu and mauri. Think about it—the very earth around Rotorua, shaped by millennia of volcanic activity, provided the raw materials for these sacred paintings. Kokowai was used to keep bad spirits away, paint faces, and colour human bones and other tapu objects. It was traded, fought over, carried from place to place. This wasn’t just paint; it was power in pigment form, literally born from the fire beneath the earth. The volcanic landscape that makes Rotorua famous today also created the very materials that would allow Māori ancestors to leave their mark for centuries.

New Zealand’s First Art Galleries

On the walls of caves and other natural shelters around New Zealand are many remarkable works of art. They are by generations of Māori, from the first Polynesian settlers who arrived over 700 years ago, to their descendants who witnessed European arrival. The large, fairly smooth and light-coloured surfaces of rock shelters or shallow caves, especially in limestone areas, provided early Māori artists with open ‘canvases’. But here’s what’s mind-blowing: Some murals extend up to 20 metres under the overhangs of limestone outcrops. Imagine standing beneath a 20-meter-wide prehistoric mural—that’s roughly the length of two school buses parked end to end, covered entirely in ancient artwork. Creating art on these rock walls gave a freedom of expression that was not restricted by structural form or function. These artists had the entire geological canvas of New Zealand at their disposal, and they used it magnificently.

A Palette Born from Earth and Chemistry

The colors these ancient artists used weren’t picked up from some prehistoric art supply store—they were literally cooked up from the earth itself. Most South Island Māori rock art was painted in black carbon that was derived from soot then mixed with oil and other ingredients. Natural deposits of iron oxide in the land provided red pigment for mixing into paint, or for use in a dry form, and the colours recorded so far range from orange through to deep carmine. But the process was surprisingly sophisticated. This involved roasting the material in a hot oven to make it more friable and bring out the colour, then crushing it to a fine powder with a kuru (stone pounder) on a large rock. Shark liver oil was used as the foundation cream with which the cosmetic was blended for application. These weren’t primitive cave painters—they were sophisticated chemists who understood how heat could transform raw materials into vibrant, lasting pigments.

The Mystery of Dating Ancient Masterpieces

Here’s a frustrating puzzle that even modern science struggles with. No exact dating of New Zealand rock art has yet been carried out. Current techniques for dating pre-historical objects, such as radiocarbon dating, do not yet provide the level of precision required for meaningful research. Neither charcoal nor kokowai can be placed on a timeline—carbon dating charcoal can tell you when a tree died, but not when it was burned, while iron oxides resist such analysis because they are non-organic. It’s like trying to solve a mystery where the most important clues refuse to give up their secrets. Dates can sometimes be estimated by examining the images themselves. Paintings of extinct birds like moa and Haast’s eagle (Aquila moorei) appear to be drawn from live observations. If so, those images are at least 500 years old, since that is approximately when those species became extinct. Sometimes the art itself becomes the timekeeper, holding secrets that our most advanced instruments can’t unlock.

The Moa Hunters’ Artistic Legacy

Rock art is the oldest surviving artistic medium with drawings starting to appear with the first wave of people into the South Island between 600 and 1000 years ago. This is now known as the ‘Moa Hunter’ period, a time when almost all of the country was heavily forested and especially around where the rock drawings are now found. Picture New Zealand as it was then—a land of giants where moa stalked through dense forests and massive Haast’s eagles ruled the skies. Perhaps the only undisputed example portraying moa features a group of three birds outlined in red with black infill, located in a small shelter in the Pareora River catchment in South Canterbury. A large black painting of an eagle on the roof of a cave in the adjoining valley also appears to date from a fairly early period. These artists were wildlife documentarians in their own right, creating what might be the world’s only artistic record of creatures that vanished forever. Moa bones and tools have been found in the floors of many shelters containing Māori rock art. These indicate that some of the birds were consumed by the occupants.

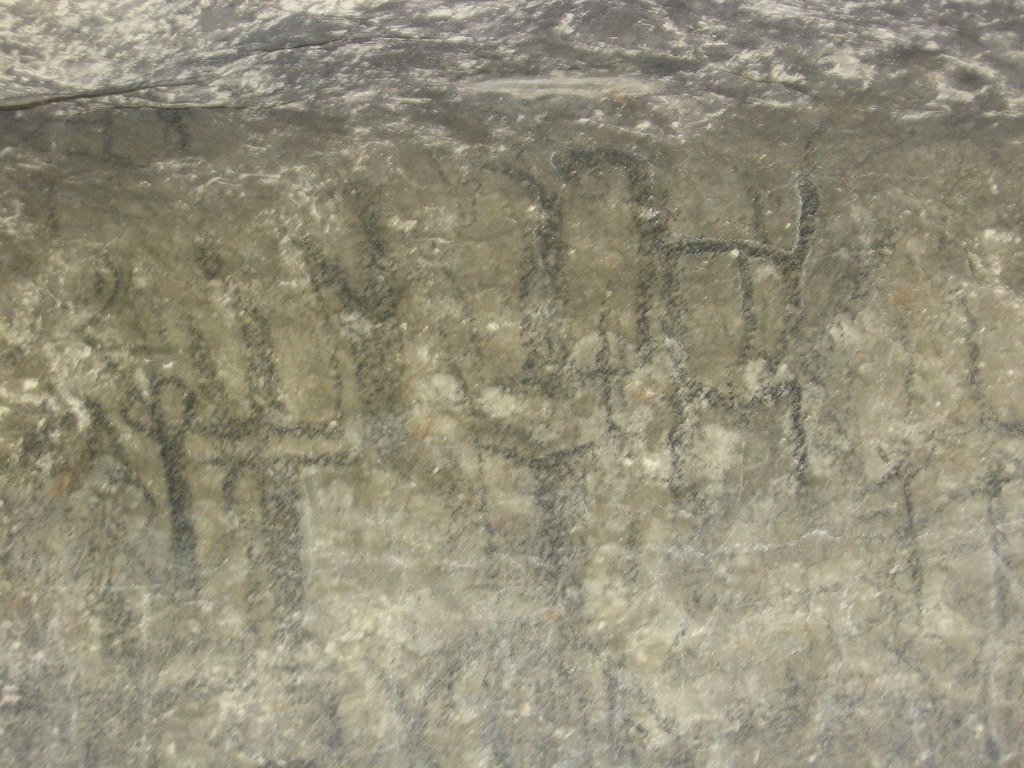

Taniwha Tales Written in Stone

Some of the most breathtaking artwork features creatures that exist only in the realm of myth and memory. Above us are three huge taniwha, spread-clawed and wide-bellied, tails looped and circled around one another, held within a panoply of organic forms—human figures, manaia, birdlike creatures, shapes too abstract, or too dim, to be properly identified—a huge fresco of sinewy bodies and charcoal limbs emerging out of the rock. Discover the famous Ōpihi Taniwha, a four-metre long, one-metre wide drawing depicting three taniwha with interlocking tails. Taniwha are supernatural beings, often associated with waterways, whose forms vary according to different tribal groups. It is breath-taking, more than a little eerie, an echo from a past that suddenly seems more recent, more living, than ever before. These aren’t just drawings—they’re spiritual guardians painted onto cave walls, protectors watching over sacred spaces for hundreds of years.

The Phantom Waka and Prophetic Art

Sometimes art and reality blur in the most unsettling ways. On 31 May, a tour group, led by renowned Māori guide Sophia, was heading out on the lake to visit the Pink and White Terraces. All the occupants of the tour boat spotted a Māori war canoe, a waka toa, but locals knew there was no war canoe on the lake and no such vessel had ever existed in the area. All accounts said that the people in the waka toa were singularly focused on the mountain. They paddled straight towards Mount Tarawera and disappeared into the mist. When informed of the mysterious sighting, the Tohunga (priest) at Te Wairoa knew that it was a portent of disaster. Eleven days later, Mount Tarawera erupted. Three of the villages surrounding the lake were obliterated and more than 150 people were killed. The waka paintings on Lake Tarawera’s shores suddenly seem less like historical records and more like prophecies painted in stone, connecting past, present, and future in ways that science can’t quite explain.

Regional Variations Tell Different Stories

Rock art in New Zealand is generally associated with the limestone shelters of the South Island, but already the New Zealand Archaeological Association lists 140 rock art sites in the North Island, most in the central plateau region. The North Island has more carvings, the South Island more drawings. Abstract motifs dominate in the North, more figurative forms in the South. It’s like different tribes spoke different artistic languages. Archaeological evidence shows that tropical Polynesian art styles introduced to New Zealand were modified gradually into regional variations. These were based on settlement patterns established by successive migrations. Birds, birdmen, fish, dogs and other animals are often depicted in South Island sites but appear to be rare in North Island rock art, based on current records. The art literally tells the story of how Polynesian culture adapted and evolved as it spread across New Zealand, creating distinct regional identities that persist today.

The Lost Art of Making Eternal Ink

The ancient artists had a secret recipe that modern paint manufacturers would envy. The tiny remnants of weka oil, shark liver oil and vegetable gum, added to the pigment to make, as ethnologist Herries Beattie was told in the early 1900s, “an ink that would stand forever”. According to one traditional southern Maori recipe for black paint, the green branches of the resinous manoao tree were burned, the smoke directed to settle against a flax mat. Scraped off, the soot was mixed with gum from the tarata (lemonwood), oil extracted from the berries of the rautawhiri (black matipo) along with weka oil. This wasn’t just art—it was chemistry, botany, and engineering rolled into one. These artists understood the properties of different oils, the chemistry of combustion, and the physics of adhesion in ways that would make modern scientists impressed. They created paints designed to last forever, and incredibly, many of them have.

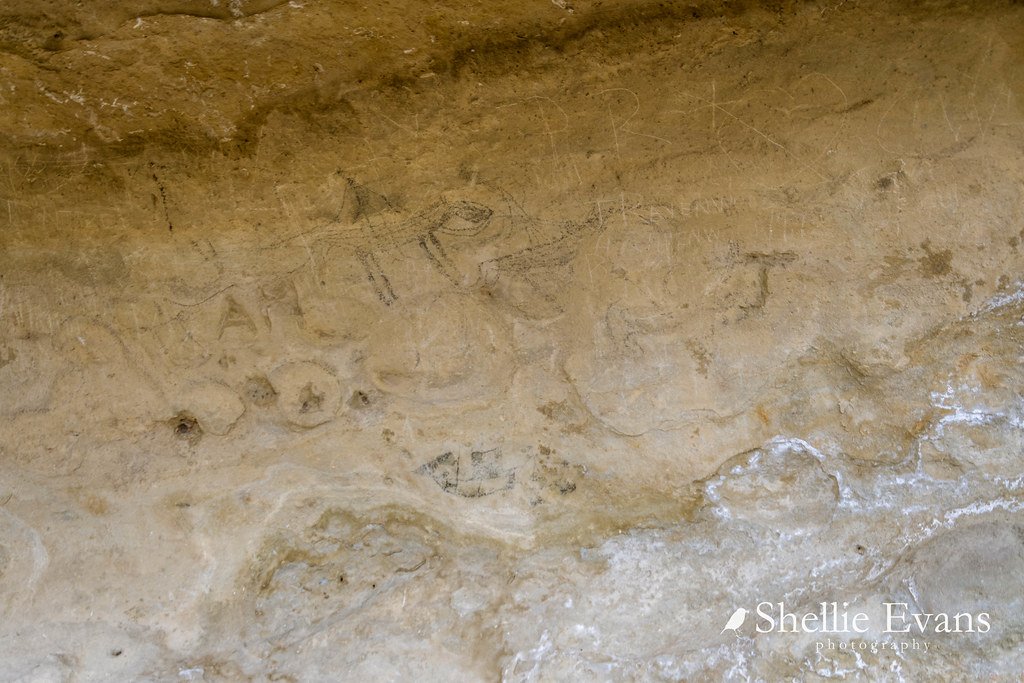

Cave Art Conservation: A Race Against Time

Unfortunately the natural “exfoliation” of the limestone has meant many of the drawings are in an advanced state of degradation. But the drawings and etchings are susceptible to gradual environmental decay and the enthusiasm of those who visit to admire them. Despite enduring for centuries, these messages from another age are gradually fading from view. It’s heartbreaking to think that art which survived for centuries is now disappearing within our lifetimes. People will get passionate about it only if they are informed, says rock art conservator Nick Tupara. A lot of people don’t know about it, or know about it only through a Marmite jar. More than 95 per cent of the art is located on private land and thus are rarely visited. These masterpieces are disappearing in isolation, hidden away where few will ever see them before they’re gone forever.

The Spiritual Chemistry of Sacred Colors

The ancient Polynesian tradition of equating red with kura (a valued possession) carried through in the Maori’s wider use of ochre as a sacred colour. Colour anything red and it was tapu: carvings, war canoes, a dead person’s house, even the scraped bones of a chief. The kokowai and shark oil combination was an effective sandfly repellent, but it also had the advantage of keeping away the dreaded patupaiarehe, or fairy folk, who were thought to be not partial to the mixture. Red wasn’t just a color—it was protection, power, and spiritual significance all rolled into one pigment. By all accounts, Maori used red ochre—kokowai—in a big way. Smearing the face with the reddish iron oxide pigment was universal with early Maori, and any contact left an indelible mark. These volcanic pigments didn’t just decorate cave walls; they decorated people, turning human bodies into living canvases painted with the earth’s own blood.

Theo Schoon: The European Who Saved Māori Art

New Zealand’s early rock art remained largely unknown, while elsewhere in the world prehistoric images such as those found in the Lascaux Caves in France greatly influenced artists such as Picasso. In 1945, however, an artist named Theo Schoon, who had gained an appreciation of non-Western art while living in Java, was struck by reproductions of rock drawings in the Otago Museum. Theo Schoon persevered, in the face of formidable difficulties, to record, interpret and celebrate Māori rock art. The government turned down his request for a car. He became ill working in exposed conditions during harsh southern winters. He sometimes had to support himself by labouring, or painting commissioned portraits for the farmers on whose land he worked. Yet he found the project deeply rewarding, both personally and artistically. ‘Again and again I have found the most surprising original creations – major artistic feats, which border on uncanny and frozen music’. This Dutch-born artist became more passionate about preserving Māori rock art than many New Zealanders, spending decades documenting treasures that might otherwise have been lost forever.

The Connection Between Rock Art and Traditional Crafts

The subjects and designs of Māori rock art are closely related to those used in tā moko (tattooing), whakairo (carvings) and decorative designs such as kōwhaiwhai (rafter patterns). All these artforms represent an intimate spiritual relationship with tupuna (ancestors), and seek the protection of the atua (gods) through them. Motifs and designs on the walls of shelters around the country run parallel, says Teira, with those seen in woodcarving, tukutuku, weaving and moko. It’s like discovering that what we thought were separate art forms were actually parts of one massive, interconnected artistic language. There isn’t anything that you can find in the rock art that you can’t find in other forms; it’s just that in other areas it becomes more stylistic. The cave paintings weren’t isolated expressions—they were part of a comprehensive visual culture that expressed identity, spirituality, and connection to ancestors through every form of creative expression.

Modern Technology Reveals Ancient Secrets

French anthropologist and rock art expert Dr Yann-Pierre Montelle uses UV light to identify layers of pigment at the Opihi taniwha site in South Canterbury. “This,” he says, “is the Lascaux of New Zealand.” Using ultraviolet light, researchers can see layers of paint invisible to the naked eye, revealing that many rock art sites were used again and again