Rising from Peru’s bone-dry coastal desert like ancient sentinels, the Moche pyramids near Trujillo stand as monuments to one of South America’s most fascinating civilizations. These massive adobe structures hold secrets that continue to shock archaeologists and rewrite our understanding of pre-Columbian societies. From ritualistic human sacrifice involving family members to breathtaking murals painted in vivid blues and reds, the Moche pyramids are far more than crumbling ruins—they’re windows into a complex world where religion, politics, and power intertwined in ways that would make modern societies uncomfortable.

The Giants of Adobe: Huaca del Sol and Huaca de la Luna

Imagine walking across a desert landscape and suddenly encountering two massive pyramids that dwarf anything you’ve ever seen. The Huaca del Sol was made with 130 million adobe bricks and was the largest structure of its kind in the Americas at about 50 metres high. Archaeologists estimate that over 130 million adobe bricks were used, making it the largest pre-Columbian adobe structure in the Americas. Even after centuries of erosion and Spanish colonial looting, this Temple of the Sun still stands 135 feet tall, commanding respect from anyone who approaches it. Huaca de la Luna, on the other hand, is smaller but in much better condition. It was also built with adobe bricks and you can see that clearly when you go inside. These weren’t just buildings—they were statements of power that could be seen for miles across the desert.

A Civilization Born from Floods and Innovation

The Moche civilization flourished in northern Peru with its capital near present-day Moche, Trujillo, Peru from about 100 to 800 AD during the Regional Development Epoch. What makes their story even more remarkable is how they transformed disaster into opportunity. The ancient adobe building bricks were created by El Niño rainfall. In Spanish, El Niño de Navidad means “the little Christmas boy” describing oceanic Oscillation when the warm water in the Pacific near South America is at its warmest around December, causing heavy rain and subsequent floods. Instead of simply enduring these catastrophic floods, the Moche ingeniously carved their building materials directly from the clay deposits left behind. Moche society was agriculturally based, with a significant level of investment in the construction of a sophisticated network of irrigation canals for the diversion of river water to supply their crops. They turned one of nature’s most destructive forces into the foundation of their architectural legacy.

The Engineering Marvel Behind Million-Brick Monuments

Building with adobe might sound primitive, but the Moche’s construction techniques were anything but simple. The geological profile of La Huaca del Sol is characterized by the use of adobe bricks made from a mixture of mud, straw, and water. The adobe bricks were formed by hand and dried in the sun, and they were then used to construct the massive platform and buildings that make up the temple. The soil and clay were mixed with straw and water to create a pliable mud mixture that was then molded into bricks. The bricks were left to dry in the sun, which took several weeks. Think of it like an ancient assembly line where thousands of workers shaped and dried millions of bricks under the scorching desert sun. The technique involved adding new layers of bricks directly on top of the old ones. By 450 AD, eight different stages of construction had been completed. The technique involved adding new layers of bricks directly on top of the old ones. Each generation literally built upon the achievements of their ancestors, creating architectural time capsules.

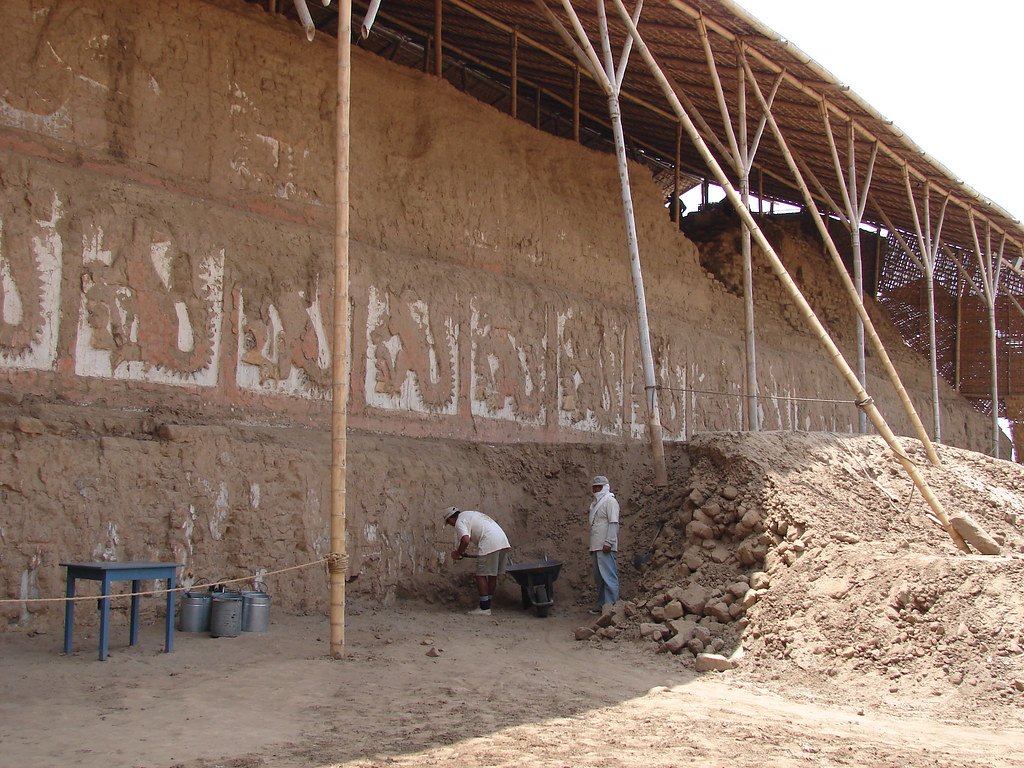

When Building Upward Meant Burying the Past

The temple is really a series of superimposed structures built over six centuries. When one temple fell out of use, the Moche simply built another on top of it, burying old murals and creating new ones, and leaving behind a mosaic of altars and walls. This wasn’t laziness—it was genius. Every time the Moche decided to expand or renovate, they preserved the old structure by carefully filling it with adobe bricks and building on top. When the Moche built a new temple, they filled in the previous one with adobe bricks, thereby hiding the old murals. Uncovering the murals, without damaging them, is a painstaking process for archaeologists. It’s like opening a perfectly preserved time capsule where each layer tells the story of a different era. Modern archaeologists have to work like forensic investigators, carefully peeling back centuries of construction to reveal the treasures hidden beneath.

Colors That Refuse to Fade: The Moche Mural Masterpieces

At the time of construction, it was decorated in registers of murals that were painted in black, bright red, sky blue, white, and yellow. The sun and weather has since utterly faded these murals away. However, the protected interior murals still burst with color that would impress any modern artist. Covering 200 square feet (19 square meters) in the corner of one of the temple’s plazas, the polychrome relief vividly portrays scenes from the spiritual life of the Moche. Human sacrifice, for instance, was a common ritual in this culture. It’s shown here in mid-action, with the perpetrator thrusting a weapon at the defenseless victim, who is splayed on his back. These aren’t just decorative paintings—they’re narrative masterpieces that tell stories of gods, rituals, and daily life with stunning detail. The mural includes many animals—fish and crayfish (presumably from the nearby Moche River), as well as snakes, scorpions, monkeys, foxes, buzzards, an unidentified feline, and dogs that appear to be barking. It also may show scenes from daily life—people capturing birds with nets, fishing from a kind of reed boat still used locally today, even smelting gold.

The Decapitator God: Art That Makes You Shudder

Moche iconography features a figure, which scholars have nicknamed the “Decapitator” or Ai Apaec. It is frequently depicted as a spider, but sometimes as a winged creature or a sea monster. Together, all three features symbolize land, water, and air. When the body is included, the figure is usually shown with one arm holding a knife and another holding a severed head by the hair. Imagine walking through these temples 1,500 years ago and seeing these terrifying images staring down at you from every wall. The friezes include representations of the creator god Ayapec, who sometimes resembles a half man-half jaguar and other times is depicted as a horrific spider-like creature frequently referred to as “The Decapitator.” It should be noted that the priests ritually consumed San Pedro cactus, which contains the hallucinogenic drug mescaline. This may help explain the nightmarish nature and appetites of the deities they communed with as well as the intense palette of colors displayed on the pyramid’s facade. The Moche weren’t creating art for art’s sake—they were creating visual narratives that reinforced their religious beliefs and social hierarchy through fear and awe.

Human Sacrifice: Not Just War Captives

For decades, archaeologists assumed that Moche human sacrifice primarily involved captured enemies. Archaeologists working in northern Peru have proposed that victims of Moche sacrifice represented either local Moche warriors defeated in ritual battles or enemy soldiers captured in warfare with nonMoche or competing Moche polities. When iconographic analysis, mortuary treatment, and the available archaeological data are considered, it appears that—contrary to the prediction of the ritual battle model—the Huaca de la Luna sacrificial victims were drawn not from the local Moche population but from a number of competing Moche polities. Roughly 70 sacrifice victims have been found there so far—an indication of frequent human offerings. That alone suggests the slaughter of captured warriors rather than rare killings of elites to appease the gods in religious rituals, Verano says. The evidence paints a picture of systematic, organized killing that served both religious and political purposes. “You don’t deny a proper burial, deflesh, mutilate, and turn your elites’ bones into trophies as they did [at Huacas de Moche],” says Verano, whose work has been partly supported by National Geographic Society grants. “You don’t make a drinking mug out of your elite [ruler’s] skull.”

The Shocking Discovery: Family Members as Sacrifice Victims

In a groundbreaking 2024 study that made international headlines, researchers uncovered something that no one expected. Archaeologists have revealed a previously undocumented form of ritual sacrifice involving close relatives among the elites of an ancient culture. For a study published in the journal PNAS, a team of researchers analyzed a number of previously discovered burials associated with the pre-Hispanic Moche archaeological culture, which flourished along the north coast of what is now Peru between the 4th and 10th centuries. Two teenagers who were strangled 1,500 years ago as part of an ancient Andean funeral rite were closely related to the adults they were buried with, according to a new genetic study. But surprisingly, it seems that the adolescent boy was sacrificed upon his father’s death and the adolescent girl was sacrificed when her aunt died — in a ritual archaeologists have never seen before. This discovery fundamentally changes our understanding of Moche society and the lengths they went to honor their elite dead.

The Lady of Cao: Peru’s Ancient Queen

In 2005, archaeologist Régulo Franco — led, he says, by a shamanic dream scape vision of a young female puma — discovered the intact tomb of the Lady Cao, a young woman adorned with the regalia of a high Moche religious and political leader. Her arms were decorated with tattoos of snakes and spiders, indicating she was imbued by her people with mystical powers. This woman, who died around 300 C.E., shortly after giving birth, is believed to have been the first known female ruler of pre-Columbian Peru — a Cleopatra of South America. Her discovery revolutionized our understanding of gender roles in ancient Peru. It held the remains of six people, including the well-preserved body of a high-status woman nicknamed Señora de Cao [Lady of Cao]. Three men were also placed in the tomb, as well as two adolescents who had been strangled with plant fiber ropes. The genetic analysis revealed that these weren’t random sacrifices—they were family members accompanying their relative into the afterlife.

2024’s Groundbreaking Discovery: The Queen’s Throne Room

At the site of Pañamarca, a monumental center belonging to the Moche people, who controlled northern Peru’s coastal valleys between around a.d. 350 and 850, archaeologists have discovered the first evidence of a throne room designed for a Moche queen. This was a center of unparalleled creativity during the seventh and eighth centuries a.d. Thrilling discoveries in 2024 revealed that it was also a place that defied traditional ideas about political power and divine authority. While working in a large pillared hall, a team led by archaeologists Jessica Ortiz Zevallos of the Archaeological Landscapes of Pañamarca program, Lisa Trever of Columbia University, and Michele Koons of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science unearthed extremely well-preserved murals executed in vivid blue, red, and yellow depicting four scenes that highlight a powerful woman. One panel shows the woman receiving a procession of visitors, and in another, she is seated on a throne. Even more stunning than the paintings is physical evidence of an adobe throne whose back support is eroded from having been leaned against. For the first time, archaeologists found direct evidence of where a Moche queen actually ruled from her throne.

The Collapse: When the Gods Failed

There are several theories as to what caused the demise of the Moche political structure. Some scholars have emphasized the role of environmental change. Studies of ice cores drilled from glaciers in the Andes reveal climatic events between 536 and 594 CE, possibly a super El Niño, that resulted in thirty years of intense rain and flooding followed by thirty years of drought, part of the aftermath of the climate changes of 535–536. These weather events could have disrupted the Moche way of life and shattered their faith in their religion, which had promised stable weather through sacrifices. Imagine the psychological impact on a society that had built its entire religious system around controlling the weather through human sacrifice. Then something destroyed their way of life. And it could also threaten ours! When decades of extreme weather struck despite their elaborate rituals, the very foundation of their belief system crumbled. Their gods had failed them, and with that failure came the end of their civilization.

The Spanish Conquistadors’ Devastating Legacy

During the Spanish occupation of Peru in the early 17th century, colonists redirected the waters of the Moche River to run past the base of the Huaca del Sol in order to facilitate the looting of gold artifacts from the temple. The operation of the hydraulic mine greatly damaged the Huaca del Sol. In total, approximately two-thirds of the structure has been lost to erosion and such looting. The Spanish weren’t content with simply taking gold—they literally washed away two-thirds of Peru’s largest ancient structure in their greed for treasure. It was partly destroyed when Spanish Conquistadors looted its graves for gold in the 16th century. What took the Moche centuries to build was partially destroyed in decades by European treasure hunters who saw these monuments as nothing more than sources of precious metals. This destruction represents one of the greatest losses of archaeological heritage in the Americas.

Modern Archaeological Techniques Reveal Ancient Secrets

Archaeologists have been using gigapixel photography as a scientific aid since GigaPan was founded in 2008. The technology has helped record a Paleolithic site in southwestern France and the site of a Macedonian cult on the Greek island of Samothrace, for example. Amador sees two large roles for gigapixel photography in this field: first, facilitating research by allowing experts to take a close look at sites anywhere in the world; and second, giving the public a heightened appreciation of those sites. One of the Huaca de la Luna murals has been captured in billions of pixels, allowing researchers worldwide to examine details that would be impossible to see with the naked eye. Now, a composite photo in super high resolution has captured one of those murals in amazing detail, allowing anyone with a computer to zoom in for close-up views of individual figures. It seemed like the perfect subject for a gigapixel image, a panorama made of billions of pixels that capture every element in sharp detail. Technology is helping us understand ancient civilizations in ways that would have been impossible just decades ago.

The Oldest Adobe Architecture in the Americas

Discovery of the remains of an early monumental building constructed primarily of adobes at Los Morteros (lower Chao Valley, north coast of Peru) places the invention of adobe architecture before 5,100 calendar years B.P. The unique composition, internal structure, and chronology of the adobes from Los Morteros show the beginnings of this architectural technique, which is associated with El Niño rainfall and the construction of the earliest adobe monumental building in the Americas. The Moche didn’t invent adobe construction—they perfected it. On the north coast of Peru, researchers have discovered the oldest adobe architecture in the Americas, constructed with ancient mud bricks carved from natural clay deposits created by floods caused by El Nino. The pre-Hispanic bricks — carved from sedimentary layers versus created by mixing clay, temper and water — date the invention of adobe architecture to more than 5,100 years ago, according to the international research team led by archaeologist Ana Cecilia Mauricio. This places the origins of one of the world’s most enduring building techniques right in the heart of what would become Moche territory thousands of years later.