Imagine if trees could talk, their leaves whispering secrets about the underground forces stirring beneath our feet. Well, it turns out they can – and scientists are finally learning to listen. Deep beneath volcanic landscapes, magma chambers pulse with life, releasing invisible gases that seep through soil and rock. These gases don’t just vanish into thin air; they’re quietly feeding the very forests we see above ground, creating one of nature’s most remarkable early warning systems. From space, satellites now capture the subtle greening of vegetation that might signal a volcano’s awakening long before traditional monitoring tools detect any danger.

The Hidden Language of Underground Fire

When magma begins its ascent through Earth’s crust, it’s like a slow-motion explosion happening right beneath our feet. As magma rises through the crust, it releases large quantities of carbon dioxide. This CO2 rapidly ascends to the surface and is emitted to the atmosphere either through an active volcanic vent or diffusely through the soil. Think of it as volcanic breathing – a massive underground lung system exhaling gases that have been trapped for millennia. At many active volcanoes, these diffuse soil emissions represent a significant (~30-50%) percentage of the total CO2 emissions of the volcano. This creates an invisible cloud of carbon dioxide that blankets the surrounding landscape, and surprisingly, the local vegetation absolutely loves it. The trees and plants don’t just tolerate this extra CO2 – they feast on it like diners at an all-you-can-eat buffet.

When Plants Become Volcanic Detectives

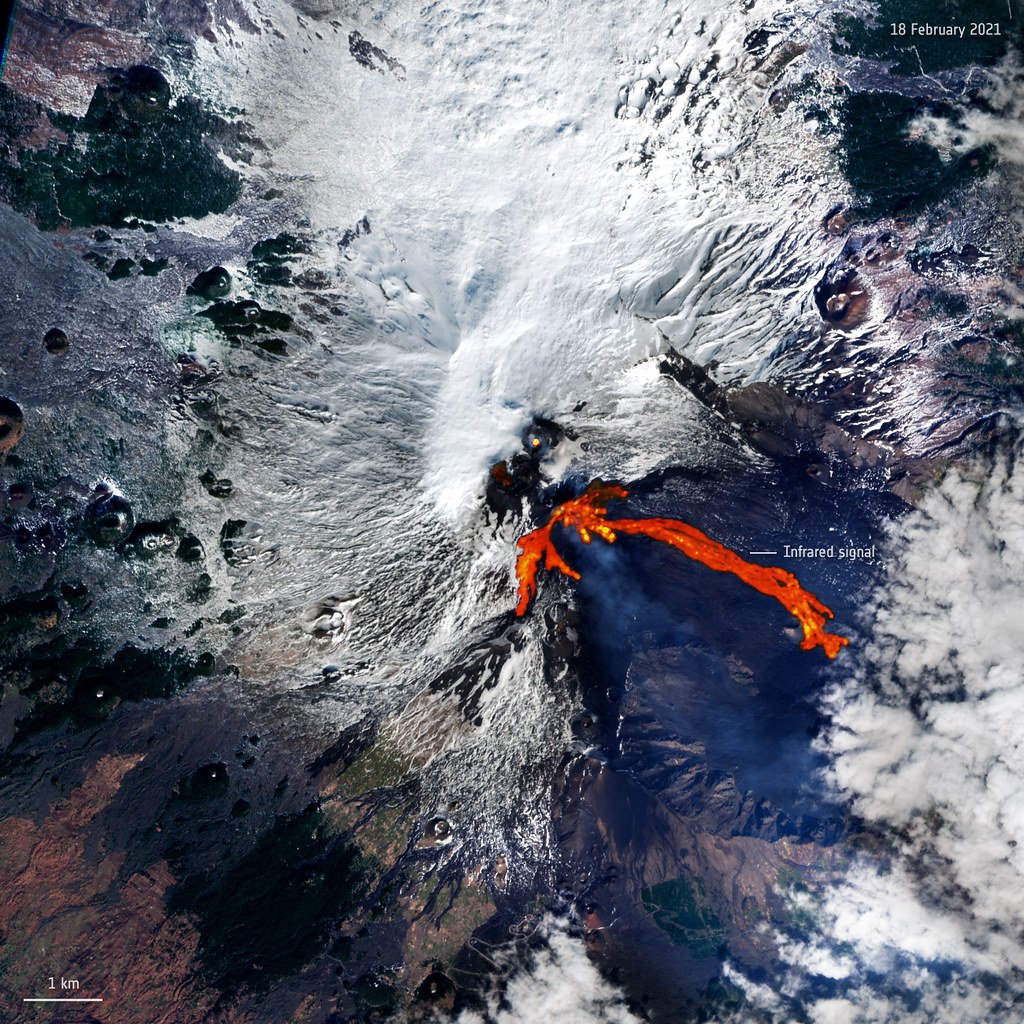

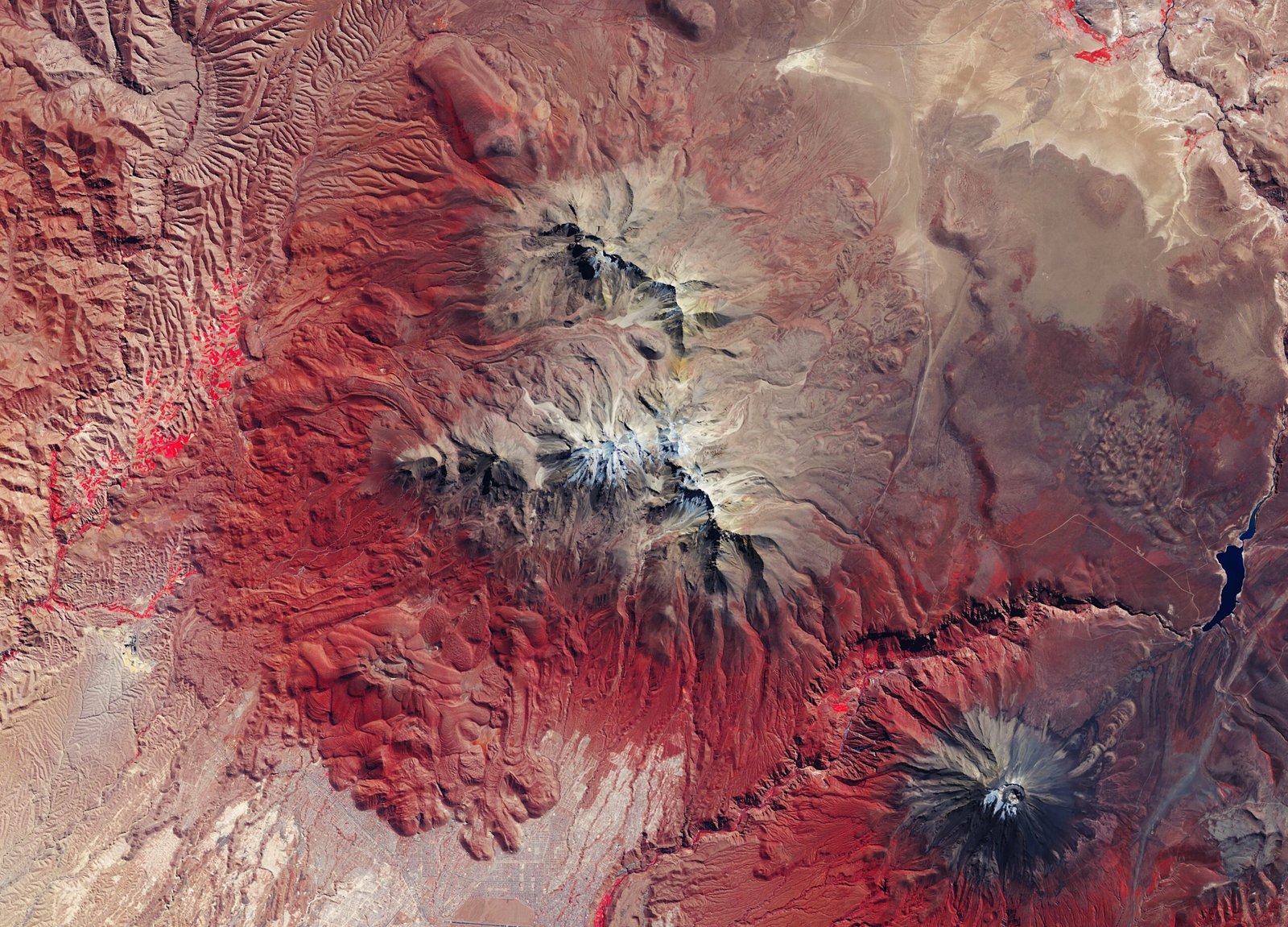

Plants adjust how they grow when their surroundings shift. This adjustment includes changes in photosynthesis and patterns in leaf structure. Variations in carbon dioxide, sulfur, and soil temperature can affect how trees flourish, and these factors often emerge in volcanic settings. It’s fascinating how nature turns ordinary forest plants into unwitting volcanic monitoring stations. Remote Sensing of Environment revealed a strong correlation between the carbon dioxide and trees around Mount Etna in Italy. Using pictures taken by Landsat 8 and other Earth-observing satellites between 2011 and 2018, the study’s authors showed 16 clear spikes in both the amount of CO2 and vegetation’s greenness, which coincided with upward migrations of magma from the volcano. The trees essentially become living barometers, their increased greenness serving as a visual thermometer for underground volcanic activity. What’s remarkable is how this biological response can be detected months or even years before conventional volcanic monitoring equipment picks up seismic activity.

The Carbon Dioxide Feast That Changes Everything

Trees that take up the carbon dioxide become greener and more lush. These changes are visible in images from NASA satellites such as Landsat 8, along with airborne instruments flown as part of the Airborne Validation Unified Experiment: Land to Ocean (AVUELO). Picture a tropical forest during its most vibrant growing season – that’s what volcanic CO2 does to ordinary trees. The concentration of CO2 outside the leaf strongly influences the rate of CO2 uptake by the plant. The higher the CO2 concentration outside the leaf, the greater the uptake of CO2 by the plant. This biological response happens because plants essentially get supercharged nutrition from the volcanic emissions. All plants grow well at this level but as CO2 levels are raised by 1,000 ppm photosynthesis increases proportionately resulting in more sugars and carbohydrates available for plant growth. The result is vegetation that becomes noticeably lusher, greener, and more vibrant than surrounding areas unaffected by volcanic gases.

Satellites as Nature’s High-Tech Translators

Satellites can now detect one of the first signs that a volcano is about to erupt. Until now, these subtle color changes could be observed only from the ground — but researchers have recently found a way to monitor them from space. A new collaboration between NASA and the Smithsonian Institution could “change the game” when it comes to detecting the first signs of a volcanic eruption, volcanologists said in a statement published by NASA earlier this month. Think of satellites as cosmic magnifying glasses, capable of spotting changes in vegetation health that would be invisible to the naked eye from ground level. We present results from satellite detection of plant responses to CO2 at the Tern Lake hydrothermal area in Yellowstone, WY from 1984 to present. As hydrothermal activity increased, NDVI (normalized differential vegetation index) values in the forested areas immediately surrounding the hydrothermal area increased as compared to nearby forests which were unaffected by hydrothermal activity. These space-based sensors can monitor vast areas continuously, creating a comprehensive surveillance network that never sleeps.

The NDVI Revolution in Volcanic Monitoring

Landsat Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is used to quantify vegetation greenness and is useful in understanding vegetation density and assessing changes in plant health. NDVI works like a health monitor for vegetation, measuring how much light plants reflect in different wavelengths. The pigment in plant leaves, chlorophyll, strongly absorbs visible light (from 400 to 700 nm) for use in photosynthesis. The cell structure of the leaves, on the other hand, strongly reflects near-infrared light (from 700 to 1100 nm). The more leaves a plant has, the more these wavelengths of light are affected. When volcanic CO2 enriches the soil and atmosphere, plants respond by producing more chlorophyll and developing denser foliage. A positive NDVI anomaly is indicative of excessive photosynthetic plant activity. Scientists can track these changes over time, creating time-lapse movies of volcanic landscapes that reveal the hidden story of underground magma movement through the language of changing vegetation.

Early Warning Signs Written in Leaves

We show that active and potentially eruptive areas in a VRZ can be detected up to 2 years before the arrival to the surface of the final eruptive dyke and venting of lava flows by processing satellite images applying a Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) algorithm. This is perhaps the most stunning discovery in volcanic monitoring – plants can literally predict eruptions years before they happen. Based on the plant responses there also appears to have been a previously unrecognized period of hydrothermal activity at this location in the early-mid 1980s, around 15 years before hydrothermal activity was directly observed to have begun. It’s like having a biological time machine that reveals the hidden history of volcanic activity. The remote detection of carbon dioxide greening of vegetation potentially gives scientists another tool — along with seismic waves and changes in ground height—to get a clear idea of what’s going on underneath the volcano. This biological early warning system provides a crucial safety buffer, potentially allowing evacuations and preparations to begin well before traditional monitoring methods would raise an alarm.

The Dark Side of Volcanic Vegetation Response

Not all volcanic interactions with plants tell a story of thriving growth. The sulfuric acid droplets in vog have the corrosive properties of dilute battery acid. When vog mixes directly with moisture on the leaves of plants it can cause severe chemical burns, which can damage or kill the plants. Volcanic smog, or “vog,” represents the destructive flip side of volcanic plant interactions. Sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas can also diffuse through leaves and dissolve to form acidic conditions within plant tissue. While carbon dioxide acts like plant food, sulfur compounds work more like plant poison. Here, enhanced soil temperatures >50°C, detected by thermal infrared imaging, and extremely high carbon dioxide and sulfur emissions created an acid-sulfate zone, evidenced by smoking fumaroles and the distinctive rotten egg smell of hydrogen sulfide. Together, this caused extreme stress to the trees, something visible in the Landsat images before being detected by other satellites. This creates a complex pattern where some areas show enhanced plant growth while others exhibit severe vegetation stress, giving scientists multiple indicators to interpret volcanic activity.

Ground Truth: What Researchers Find in the Field

Alexandria Pivovaroff of Occidental College measures photosynthesis in leaves extracted from trees exposed to elevated levels of carbon dioxide near a volcano in Costa Rica. Fisher directed a group of investigators who collected leaf samples from trees near the active Rincon de la Vieja volcano in Costa Rica while also measuring carbon dioxide levels. “Our research is a two-way interdisciplinary intersection between ecology and volcanology,” Fisher said. Field research provides the crucial link between satellite observations and actual volcanic processes. Scientists brave volcanic terrain to collect leaf samples, measure soil gases, and validate what satellites observe from space. An exploratory study at Turrialba volcano in Costa Rica found a correlation between soil CO2 fluxes and heavier ẟ13C values in wood from nearby trees, which suggests that those trees incorporated significant amounts of volcanic CO2. These on-ground measurements reveal the intimate chemical relationship between volcanic emissions and plant biology, confirming that trees literally incorporate volcanic gases into their tissue structure.

The Yellowstone Case Study: A Living Laboratory

Robert Bogue, a Ph.D. researcher at McGill University, Montreal, Canada, and colleagues monitored plant responses to volcanic emissions in the Tern Lake thermal area of the Yellowstone Caldera, Wyoming, U.S., to determine their reaction to hydrothermal activity (circulating fluids in the vicinity of a magma source producing hot water and steam). The research team used remotely-curated Landsat images from the United States Geological Survey across an area of ~33,000 m2, taken from satellites orbiting the Earth between 1984 and 2022, and compared plant health in the hydrothermal area with that in nearby forests unaffected by volcanic activity. Yellowstone serves as a perfect natural laboratory because it’s been extensively monitored for decades. The significant decline in NDVI as an indicator of plant health since the early 2000s is evident in the Tern Lake thermal area (d) compared to three comparative nearby sites (a-c). The physical shift in vegetation health through the study period was also tracked by selecting locations within the Tern Lake thermal area that had the highest NDVI value each year, monitoring movement of the hydrothermal epicenter. This research demonstrates how volcanic plant responses create a living map of underground thermal activity, with vegetation health patterns literally outlining the boundaries of volcanic influence.

Success Stories: When Plant Monitoring Saves Lives

Still, Schwandner has witnessed the potential benefits of volcanic carbon dioxide observations first-hand. He led a team that upgraded the monitoring network at Mayon volcano in the Philippines to include carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide sensors. In December 2017, government researchers in the Philippines used this system to detect signs of an impending eruption and advocated for mass evacuations of the area around the volcano. This represents a real-world success story where advanced monitoring techniques, including vegetation-based observations, contributed to saving lives. The 2017 Mayon eruption could have been catastrophic for nearby communities, but early detection allowed authorities to evacuate approximately 80,000 people before the volcano exploded. While this particular case relied on traditional gas sensors, it demonstrates the life-saving potential of comprehensive volcanic monitoring that includes biological indicators. These early warning systems create crucial time windows for emergency response, turning what could be surprise disasters into manageable evacuation scenarios.

Technology Behind the Green Revolution

An 8 year-long (2005–2012) time series of half-monthly average of the Normalized Differential Vegetation Index (NDVI) is constructed at 250 m spatial resolution from the Moderate Resolution Image Spectro-radiometer (MODIS) sensor. Interpolated rainfall data is used to isolate NDVI values departing from the normal seasonal cycles. Month-to-month NDVI comparison, linear temporal trend analysis and Principal Component Analysis enable to identify a 11 × 4 km area over which ash fallout significantly affected the state of the veget The technological sophistication behind vegetation monitoring involves multiple satellite systems working in concert. NASA’s Harmonized Landsat and Sentinel-2 (HLS) project released two new products, the Landsat 30-meter Vegetation Index (HLSL30VI) and Sentinel-2 30-meter Vegetation Index (HLSSS30VI). Each product contains a suite of nine vegetation indices including greenness, vegetative moisture content, burned area, and vegetation change (see below for a full list of indices available). By providing change detection and monitoring capabilities at 30-meter spatial resolution every two to three days is extremely beneficial for agricultural applications, or really any type of phenological or seasonal vegetation monitoring. This creates an incredibly detailed and frequently updated picture of vegetation health across volcanic landscapes.

Limitations and Challenges of Biological Monitoring

Relying on trees as proxies for volcanic carbon dioxide has its limitations. Many volcanoes feature climates that don’t support enough trees for satellites to image. In some forested environments, trees respond differently to changing carbon dioxide levels. And fires, changing weather conditions, and plant diseases can complicate the interpretation of satellite data on volcanic gases. The biological approach to volcanic monitoring isn’t foolproof – it requires the right environmental conditions to work effectively. While it is useful as a precursory warning to supplement other forms of remote sensing to anticipate volcanic hazards, the technique is currently limited to locations with relatively homogenous vegetation species as this can impact NDVI values. It also poses challenges for areas prone to drought or wildfires, which are non-volcanic stresses that may skew results, while volcanic areas at high elevations or in arid zones may have sparse tree cover that inhibits NDVI measurements. Scientists must carefully distinguish between volcanic effects and other environmental stresses that can affect plant health, making this technique most effective when combined with traditional monitoring methods.

From Destruction to Regeneration: The Volcanic Plant Cycle

Plants are destroyed over a wide area, during an eruption. The good thing is that volcanic soil is very rich, so once everything cools off, plants can make a big comeback! The relationship between volcanoes and vegetation follows a dramatic cycle of destruction and renewal. For example, on the rainy side of the island of Hawai’i, flows that are only 2 years old already have ferns and small trees growing on them. Probably in 10 years they’ll be covered by a low forest. On the dry side of Hawai’i there are flows a couple hundred years old with hardly a tuft of grass in sight. This illustrates how climate dramatically affects volcanic recovery rates. The types of plants surviving and recovering after volcanic activity largely depend upon the type of activity that takes place, the nutrient content of material ejected or moved by the volcano, the distance from the volcanic activity, and the types of vegetation propagules that survive in place or are transported from adjacent areas. Nature’s resilience in volcanic landscapes is remarkable, with some areas transforming from moonscape devastation to lush forest in just decades.

Climate Change and Volcanic Plant Interactions

While elevated levels of CO2 can help plants grow, the impacts of climate change mean it’s not all good news for the plant world. The intersection of climate change and volcanic plant responses creates a complex web of interactions that scientists are still trying to understand. Climate change is also expected to bring more combined heat waves and droughts, which would likely offset any benefits from the carbon fertilization effect. This means that the CO2 enrichment from volcanic sources might be less beneficial in a warming world. In addition, when soils are dry, plants become stressed and do not absorb as much CO2, which could limit photosynthesis. Scientists found that even if plants absorbed excess carbon for photosynthesis during a wet year, the amount could not compensate for the reduced amount of CO2 absorbed during a previous dry year. Climate change may therefore reduce the reliability of vegetation-based volcanic monitoring, as stressed plants might not respond as predictably to volcanic CO2 emissions. This adds another layer of complexity to an already challenging field of research.

The Future of Green Volcanic Monitoring

A new collaboration between NASA and the Smithsonian Institution could “change the game” when it comes to detecting the first signs of a volcanic eruption, volcanologists said in a statement published by NASA earlier this month. These signs can help to protect communities against the worst effects of volcanic blasts, including lava flows, ejected rocks, ashfalls, mudslides and toxic gas clouds. The future of volcanic monitoring increasingly relies on sophisticated integration of satellite technology, artificial intelligence, and biological indicators.