Every time archaeologists uncover an ancient jaw or carefully extract fossilized teeth from sediment layers, they’re holding thousands of years of history in their hands. These seemingly simple white structures have become some of our most revealing windows into the lives of our earliest ancestors. In laboratories around the world, scientists are discovering that ancient hominin teeth hold far more secrets than anyone ever imagined—secrets about what they ate, how they lived, how they grew up, and even details that challenge everything we thought we knew about human evolution.

The Revolutionary Discovery of Protein Preservation in Ancient Enamel

The field of ancient human studies took a stunning turn recently when researchers published groundbreaking work in the journal Science showing that proteins can survive in tooth enamel for over 2 million years, extracted from four Paranthropus robustus individuals. This new research overcomes barriers using paleoproteomics, a method that analyzes long-preserved proteins found in tooth enamel. Think of tooth enamel as nature’s perfect time capsule—harder than steel and more durable than any human-made material. Unlike DNA, which crumbles to dust in Africa’s heat after just 20,000 years, proteins locked within enamel crystals can survive eons. This approach allowed researchers to extract and sequence proteins from the enamel of the four hominin fossils discovered in the Swartkrans cave, a site located in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage area. For the first time in history, we can literally read the molecular signatures of our ancient relatives and discover things about them that bones and stones never could tell us.

Challenging Gender Assumptions From Two Million Years Ago

One of the study’s most surprising discoveries came from sex determination. By analyzing AMELY and AMELX proteins, which are sexually dimorphic, the team found that two specimens were male and two were female. But here’s where it gets fascinating—scientists had been wrong about these individuals for decades. The molecular analysis contradicted previous assumptions based on tooth size and morphology. One individual, believed to be female due to its small teeth, was identified as male through its protein profile. Imagine the implications: if we’ve been misidentifying the sex of ancient hominins based on tooth size, how many other assumptions about their social structures and behaviors need rethinking? This finding has profound implications for paleoanthropology, as it challenges a long-standing method used to interpret the fossil record. The ability to correctly sex individuals using protein data offers a more reliable alternative.

Evidence of Unknown Species Hidden in Plain Sight

Perhaps most shocking of all, while analyzing the protein sequences, the team observed genetic variation among the individuals that couldn’t be explained by sex alone. One individual — labeled SK-835 — was especially intriguing. Its amino acid profile showed it was more distantly related to the other three, raising the possibility that it belonged to a distinct species of hominin previously unrecognized by scientists. We’re talking about a completely unknown branch of the human family tree that’s been sitting in museum collections, waiting to be discovered. This isn’t just an academic footnote—it suggests that the story of human evolution is far more complex than our textbooks suggest. Although it is “premature to classify SK-835 as a member of the newly proposed Paranthropus [capensis] taxa,” the variation still suggests a deeper phylogenetic complexity. Another explanation could be microevolutionary differences among geographically or temporally separated populations.

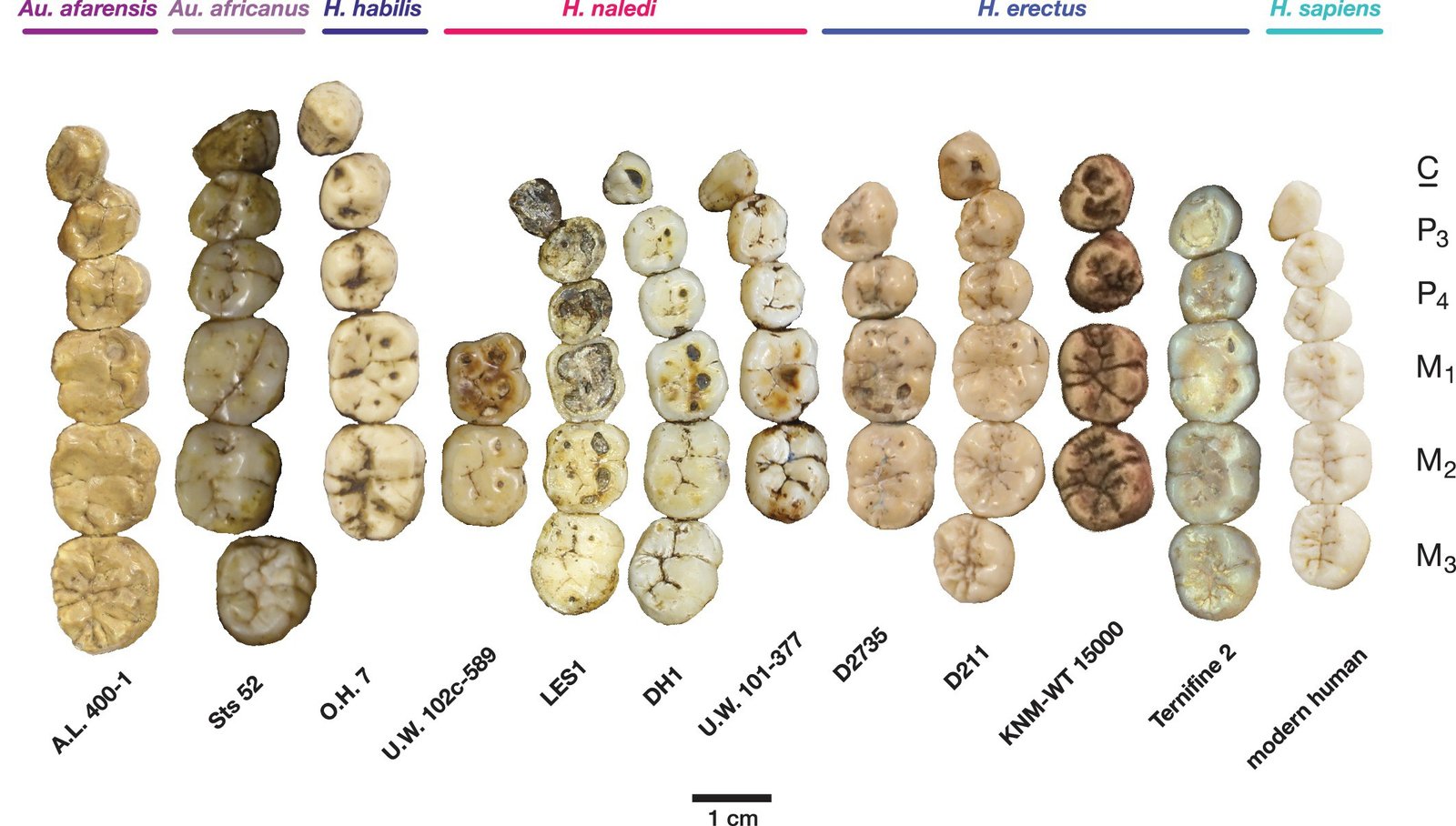

The Shocking Truth About Nutcracker Man’s Diet

For decades, scientists looked at Paranthropus boisei and saw a creature perfectly designed for crushing nuts and tough plant materials. Paranthropus boisei has the biggest, flattest cheek teeth, and the thickest dental enamel of any known member of our tribe, the Hominini. It’s cranium and mandible appear built to resist the stresses associated with heavy chewing, and provide copious attachment areas for massive muscles of mastication. It is no surprise then that P. boisei has been widely considered to have been a hard-object feeder, specializing on nuts and seeds. But when researchers finally examined the microscopic wear patterns on their teeth, they discovered something that turned decades of assumptions upside down. These all show relatively low complexity and anisotropy values. This suggests that none of the individuals consumed especially hard or tough foods in the days before they died. The evidence suggests these “Nutcracker” hominins weren’t cracking nuts at all—they were likely eating soft grasses and other gentle foods, using their massive dental machinery as backup equipment for tough times.

Microwear Patterns Reveal Daily Dining Habits

Reconstructing the diets of extinct hominins is essential to understanding the paleobiology and evolutionary history of our lineage. Dental microwear, the study of microscopic tooth-wear resulting from use, provides direct evidence of what an individual ate in the past. Picture this: every time our ancestors chewed, they were essentially creating a microscopic diary of their meals. These tiny scratches, pits, and wear patterns are like fingerprints of ancient diets. The chewing simulator imitates a human jaw to reveal how noshing on different foods impact the teeth, looking to see whether those foods leave tiny abrasions on the machine’s “teeth.” She and her colleagues have already discovered that meat doesn’t leave microwear signatures, which could change how scientists analyze the teeth of hominins believed to be particularly carnivorous, like Neanderthals. Think about what this means: some of our assumptions about meat-eating ancestors might need a complete revision. Results for living primates show that this approach can distinguish among diets characterized by different fracture properties. When applied to hominins, microwear texture analysis indicates that Australopithecus africanus microwear is more anisotropic, but also more variable in anisotropy than Paranthropus robustus.

Chemical Signatures That Tell Stories of Ancient Migrations

The analyses of the stable isotope ratios of carbon (δ13C), nitrogen (δ15N), and oxygen (δ18O) in animal tissues are powerful tools for reconstructing the feeding behavior of individual animals and characterizing trophic interactions in food webs. Of these biomaterials, tooth enamel is the hardest, most mineralized vertebrate tissue and therefore least likely to be affected by chemical alteration. Imagine being able to trace exactly where an ancient human lived and what they ate just by analyzing the chemistry of their teeth. In this study, we show that the nitrogen isotope composition of organic matter preserved in mammalian tooth enamel (δ15Nenamel) records diet and trophic position. The δ15Nenamel of modern African mammals shows a 3.7‰ increase between herbivores and carnivores as expected from trophic enrichment. These chemical signatures can reveal whether someone spent their childhood in a coastal environment versus inland, or whether they moved between different ecological zones during their lifetime. It’s like having a geological GPS system embedded in their teeth that tracks their entire life journey.

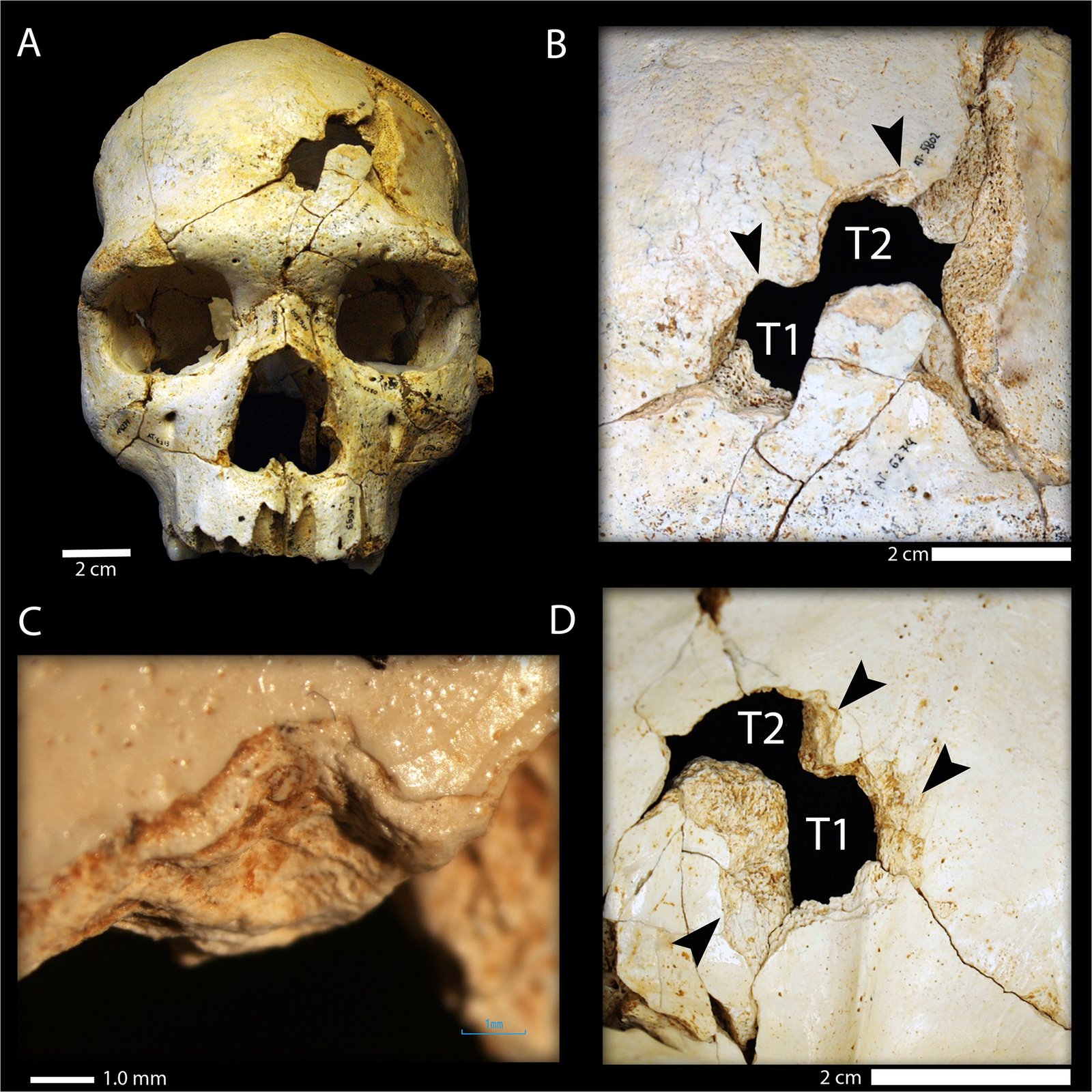

The Mystery of Accelerated Brain Growth in Neanderthal Children

So this little baby maxilla goes with this major brain, and if it was the case that this died at four or five years of age, it’s a pretty rapid period of growth and development. As it turned out, counting these tiny timelines, we estimated this was a three-year-old. So by three years of age, this Neanderthal had grown a brain bigger than most of us. The implications are staggering: Neanderthal children were developing at a pace that would seem almost superhuman by today’s standards. Scientists can determine this by examining growth lines in teeth—similar to tree rings—that record daily and weekly development patterns. It might seem that our development is invisible in the fossil record, but much can be learned from the faithful records of birth and growth embedded in teeth. This rapid brain development might explain why Neanderthals were so successful in harsh Ice Age environments, but it also raises questions about their childhood experiences and social structures. Tonight, though, I want to tell you a little bit about how Neanderthals grew and developed.

Unexpected Evidence of Extended Childhood in Early Homo

Fossil tooth development suggests an extended human growth phase occurred at least 1.77 million years ago, possibly reflecting a shift towards extended parenting and reproductive success, rather than increasing brain size. Here we show that the first evolutionary steps towards an extended growth phase occurred in the genus Homo at least 1.77 million years ago, before any substantial increase in brain size. This discovery completely flips our understanding of when humans began their uniquely long childhood periods. One of the earliest known members of the Homo genus experienced delayed, humanlike tooth development during childhood before undergoing a more chimplike dental growth spurt. The fossil teeth of a roughly 11-year-old individual reveal slowed development of premolar and molar teeth up to about age 5, followed by speeded development of those same teeth. It’s like finding evidence that human childhood evolution happened in stages—starting with slow early development, then accelerating later. The Dmanisi individual dates to a period before significant increase in brain size in humans. Modern human lifespans are relatively unusual among animals. We have prolonged childhoods and delayed maturation compared to our closest living relatives, the great apes.

Revolutionary Protein Analysis Reveals Hidden Genetic Diversity

A new study, led by Palesa Madupe of the Globe Institute at the University of Copenhagen, has revealed protein-based evidence of hidden genetic variation within Paranthropus robustus. This suggests that the prehistoric humans may not have been a single, uniform species after all. For years, scientists grouped these ancient relatives into neat categories, assuming they understood the relationships between different populations. But cutting-edge protein analysis is revealing that reality was far messier and more interesting. This hard outer layer of teeth, once dismissed as too durable to hold molecular secrets, is now offering unexpected insights into a lineage that scientists used to consider fairly straightforward. A new study has revealed protein-based evidence of hidden genetic variation within Paranthropus robustus. This suggests that the prehistoric humans may not have been a single, uniform species after all. Instead of aDNA, they turned to sturdier molecules that can remain intact in fossils for far longer, and would allow a fresh window into the biology of extinct species. A field called paleoproteomics now makes it possible to detect and characterize proteins in ancient remains. Using high-resolution mass spectrometry, researchers analyzed tooth enamel from fossils dated to roughly 1.8-2.2 million years ago.

Dietary Flexibility as the Key to Early Human Success

Current hypotheses for the evolution of the genus Homo invoke a change in foraging behavior to include higher quality foods. Recent microwear texture analyses of fossil hominin teeth have suggested that the evolution of Homo erectus may have been marked by a transition to a more variable diet. Rather than becoming specialists in any particular food source, early humans appear to have succeeded by becoming the ultimate generalists. Analyses of molar occlusal microwear have shown that African specimens assigned to early Homo differ from their australopith predecessors in their wear pattern and cusp morphology. But these differences suggest a broader diet for early Homo, not one that is necessarily focused on meat, underground storage organs, or any singular food source. Based on these and other data, Ungar and colleagues have argued that the defining adaptive dietary feature in early Homo was its versatility. This flexibility likely gave them crucial advantages during the unpredictable climate changes of the early Pleistocene period. Chemical analysis of her teeth shows that, as far back as 4 million years ago, the diets of hominins suddenly became much more diversified than other primates. Apes living in trees were still ordering off the prix-fixe menu of the jungle, whereas the more human-like hominins had expanded their palate to the buffet offerings of jungle and savannah.

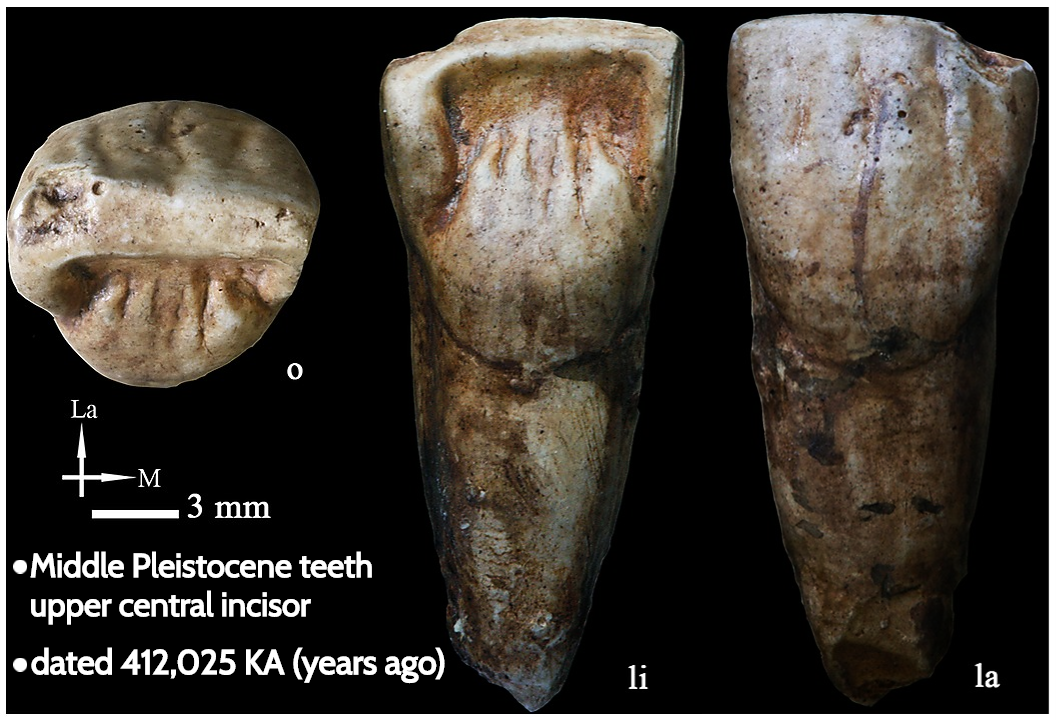

The Evolutionary Shrinking of Human Teeth

Compared to modern humans, many hominins had toothier mouths. The “Nutcracker,” (aka Paranthropus boisei), a hominin that lived 2.3 million years ago, had the largest molars and thickest enamel of any hominin. Homo erectus, which lived all over the world 1.5 million years ago, had larger canines than modern humans. But both still followed the evolutionary trend of generally decreasing tooth size. Our ancestors needed bigger, stronger teeth to handle tougher foods and more demanding diets. As cooking and food processing technologies developed, our teeth essentially became overengineered for the job. Modern humans normally end up with 32 teeth by the time they’re fully adult, including four wisdom teeth that often have to be removed because there just isn’t room for them. “This has largely been attributed to changes in dietary strategies,” Krueger said. It’s a perfect example of how culture and biology interacted throughout human evolution—as we got better at preparing food, our faces and teeth could afford to become smaller and more delicate.

Isotopic Evidence of Major Dietary Shifts in Human Evolution

Accumulating isotopic evidence from fossil hominin tooth enamel has provided unexpected insights into early hominin dietary ecology. Among the South African australopiths, these data demonstrate significant contributions to the diet of carbon originally fixed by C4 photosynthesis, consisting of C4 tropical/savannah grasses and certain sedges, and/or animals eating C4 foods. Moreover, high-resolution analysis of tooth enamel reveals strong intra-tooth variability in many cases, suggesting seasonal-scale dietary shifts. This represents one of the most fundamental changes in human dietary history—the shift from forest foods to savanna resources. This pattern is quite unlike that seen in any great apes, even ‘savannah’ chimpanzees. The overall proportions of C4 input persisted for well over a million years, even while environments shifted from relatively closed (ca 3 Ma) to open conditions after ca 1.8 Ma. What makes this even more remarkable is the seasonality evidence—our ancestors weren’t just eating different foods, they were adapting their diets throughout the year in sophisticated ways that no other primates had ever achieved.

Advanced Techniques Revolutionizing Fossil Analysis

We use two novel methods to produce high-precision stable isotope enamel data: (i) the “oxidation-denitrification method,” which permits the measurement of mineral-bound organic nitrogen in tooth enamel (δ15Nenamel), which until now, has not been possible due to enamel’s low organic content, and (ii) the “cold trap method,” which greatly reduces the sample size required. Scientists are essentially performing molecular archaeology, extracting information from samples smaller than a grain of rice. We used synchrotron phase-contrast tomography to track the microstructural development of the dentition of a subadult early Homo individual from Dmanisi, Georgia. The individual died at the age of 11.4 ± 0.6 years, shortly before reaching dental maturity. These technologies allow researchers to peer inside fossils without destroying them, reading growth patterns with incredible precision. Proteomics is inherently a destructive technique, but we take great care to minimize impact, especially when working with rare or precious specimens. The balance between preserving irreplaceable fossils and extracting maximum information requires extraordinary technical skill and innovative approaches.

Unexpected Insights From the Dmanisi Hominins

The Dmanisi hominins, typically assigned to Homo erectus, retain a number of primitive traits for the genus, including a relatively small brain, small stature, and primitive metatarsal morphology. Nonetheless, these hominins are associated with Oldowan-style stone tools and cut marks on herbivore long bones, suggesting some degree of hunting or scavenging behavior in this population. Dated to 1.8 mya, Dmanisi is the oldest hominin fossil locality outside of Africa. These Georgian fossils represent some of our first ancestors to venture beyond Africa, yet their dental evidence suggests they maintained surprisingly conservative diets.