Today’s Arctic is a land of bitterly cold winters, unceasing summer daylight, and a delicate ecology full of migrating birds. But a revolutionary finding in northern Alaska points to an avian paradise far older than we could have ever known. A wealth of 73-million-year-old fossils, including delicate bones of embryos and hatchlings, shows that birds were nesting in the Arctic during the age of dinosaurs, so distorting the record of polar breeding by an amazing 25 million years. These prehistoric birds, some looking like contemporary ducks and loons, survived despite freezing darkness, predatory dinosaurs, and a planet on almost certain disaster. In what way did they accomplish it? And what lessons about the resiliency of life in the toughest conditions on Earth should their survival provide?

A Nursery in the Cretaceous Arctic

The Prince Creek Formation in Alaska, now a frozen expanse, was once a lush coastal floodplain where dinosaurs like Pachyrhinosaurus and Troodon roamed. But hidden among their massive bones were tiny, fragile fossils of more than 50 specimens of bird remains, some no larger than a grain of rice. These belonged to hatchlings and embryos, proving that birds weren’t just passing through they were raising their young in the Arctic.

“Birds have existed for 150 million years,” says lead author Lauren Wilson, a paleontologist at Princeton University. “For half of that time, they’ve been nesting in the Arctic”. Before this discovery, the oldest evidence of polar nesting came from 47-million-year-old penguin fossils in Antarctica. Now, we know birds were braving the cold alongside T. rex’s cousins.

The Great Polar Dilemma: Migrate or Hunker Down?

Surviving an Arctic winter is no small feat, even for modern birds. But Cretaceous-era hatchlings faced an impossible choice: endure months of darkness and freezing temperatures or flee south on a 2,000-kilometer (1,240-mile) migration while barely three months old.

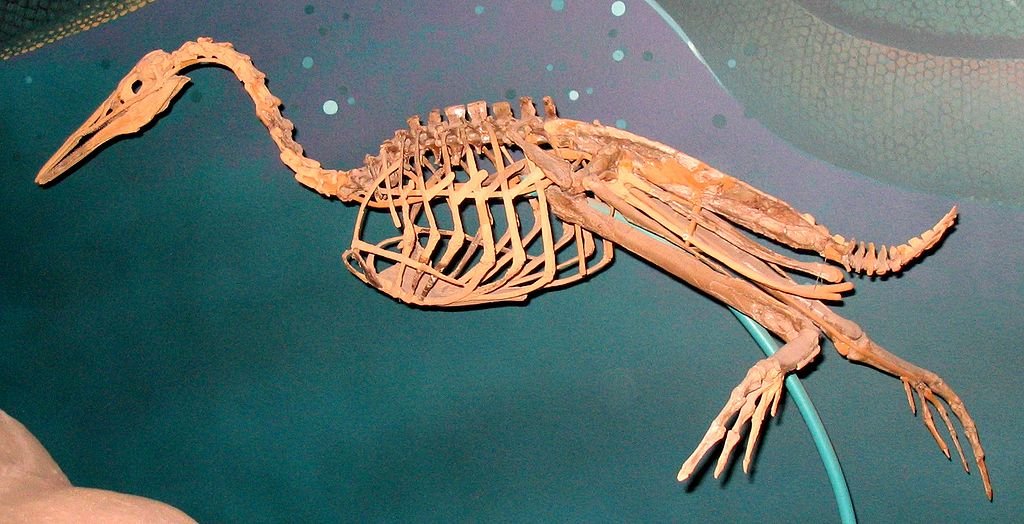

“The common conception is they’re too primitive for this advanced behavior,” Wilson admits. Yet the fossils suggest some birds pulled it off. Species like Hesperornithes (loon-like divers) and Ichthyornithes (toothed seagull relatives) may have evolved rapid growth rates, allowing chicks to mature quickly before winter hit. Others, resembling modern ducks, might have been early migrants, fleeing before the cold set in.

The Missing Birds: Why One Group Didn’t Make the Cut

Not all Cretaceous birds could handle the Arctic. Notably absent from the fossil site are Enantiornithes, a dominant group of toothed, claw-winged birds that ruled other parts of the world. Their slow growth and simultaneous feather molting (leaving them temporarily naked) would have been deadly in polar winters.

“They took years to reach adulthood,” explains co-author Daniel Ksepka. “Meanwhile, modern birds grow up in weeks.” This adaptability may explain why Enantiornithes vanished with the dinosaurs, while Arctic-hardy birds survived.

Dinosaurs on the Menu: Life as a Cretaceous Chick

Nesting in the Arctic meant sharing the neighborhood with predators. Troodon, an 11-foot (3.3-meter) carnivore with serrated teeth, “would have happily taken advantage of a bunch of cute little chicks for dinner,” says Patrick Druckenmiller, a study co-author. Even herbivores like Pachyrhinosaurus, a 2-ton relative of Triceratops could crush nests underfoot.

Yet the birds persisted, likely capitalizing on summer’s 24-hour daylight and insect booms. “The Arctic was very green,” Druckenmiller notes. “But winters? Freezing temps, snow, and four months of darkness”.

Fossil Gold Rush: Panning for Prehistoric Bones

Lifting these fossils was an endurance challenge. From Fairbanks by plane and motorboat, researchers braved -30°C (-22°F) temperatures and travelled 500 miles (800km) to reach the remote site. There, using dental tools, they plucked microfossils from sediment akin to gold prospectors.

“It was absolutely panning for gold, except bird bones were our prize,” Druckenmiller says. The work paid off; Alaska is today “one of the best places in the nation for dinosaur-age bird fossils.”

The Bigger Picture: Why This Discovery Matters

Beyond rewriting avian history, these fossils reveal a profound truth: Arctic ecosystems have been shaped by birds for tens of millions of years. “These communities are a long-term norm, not a recent innovation,” says Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh.

As climate change threatens modern Arctic birds, understanding their ancient resilience could be crucial. Did rapid growth or migration save them? Were some species more vulnerable than others? The answers lie in these tiny bones and the next fossil hunt.

What’s Next? The Hunt for More Feathered Clues

The team’s work is far from over. “We might still find a bone from a bird we didn’t know was there,” Wilson says. One burning question: Are these the oldest Neornithes the group including all modern birds? If so, they’d predate the previous record-holder by 4 million years.

For now, the Prince Creek fossils stand as a testament to life’s tenacity. Long before humans, before ice ages, even before dinosaurs went extinct, birds were already mastering the art of survival at the top of the world.

Sources:

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.