Imagine strolling through a sunlit forest and stumbling upon a small opossum lying motionless, mouth agape and eyes glazed. Your heart skips a beat—only for the creature to suddenly leap up and scurry away as if nothing happened. This eerie, almost theatrical behavior is called thanatosis, or playing dead, and it’s one of nature’s most surprising survival strategies. But why do some animals pull off this dramatic act? The answer is more fascinating than you might think, involving cunning deception, evolutionary battles, and even a dash of animal psychology.

The Art of Thanatosis: Nature’s Ultimate Bluff

Thanatosis, often called tonic immobility or “playing dead,” is a survival trick that many animals use when faced with imminent danger. Unlike freezing in place, thanatosis is a deeper, more convincing act—some animals even emit foul odors or let their tongues hang out to really sell the performance. This behavior isn’t just a random response; it’s a carefully honed tactic sculpted by millions of years of evolution. When prey animals “die” on cue, they can confuse or discourage predators long enough to escape, turning the tables in the deadly game of survival.

How Playing Dead Defeats Hungry Predators

Predators are often attracted to movement. When an animal suddenly goes limp and appears lifeless, it can confuse or bore a hungry attacker. Some predators lose interest in prey that doesn’t struggle, as they may associate stillness with illness or death, making the meal less appealing or potentially dangerous. In some cases, predators abandon their catch altogether, giving the “dead” animal a precious window to spring back to life and flee the scene.

The Opossum: The Champion of Playing Dead

If there were an Olympic medal for playing dead, the opossum would win gold every time. This North American marsupial is so famous for its skill that the phrase “playing possum” has entered everyday language. When threatened, opossums collapse, drool, and emit a putrid stench from their anal glands, mimicking the scent of rotting flesh. This convincing performance can last from a few minutes up to several hours, depending on the threat. It’s a risky move, but for the opossum, it’s a life-saver more often than not.

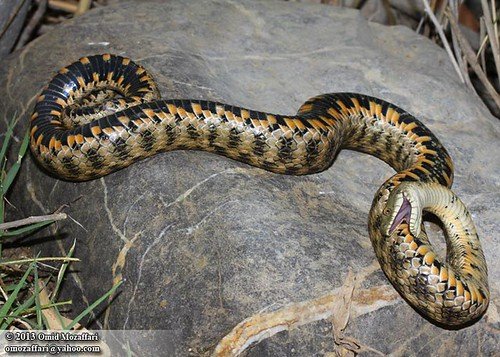

Snakes and Reptiles: Masters of Deception

Several species of snakes, such as the hognose snake, are accomplished actors when it comes to playing dead. These snakes will flip onto their backs, stick out their tongues, and even emit a musky odor reminiscent of decay. Some will wriggle dramatically before going perfectly still, as if letting the predator know, “You got me.” This act often convinces larger animals like birds or mammals to move along, thinking the snake is already dead or diseased.

Insects That Fool Their Enemies

Even tiny creatures like beetles, ants, and certain caterpillars have evolved their own versions of thanatosis. When threatened, they drop to the ground and remain perfectly still, blending in with dirt or leaves. This strategy is especially effective against predators like birds or spiders, who rely heavily on movement to spot their prey. For example, the common ladybug will tuck in its legs and stay motionless, sometimes even excreting toxic chemicals to make itself extra unappealing.

Birds and Thanatosis: Not Just for the Grounded

Birds might seem too flighty for such a passive defense, but several ground-nesting species have been observed playing dead, especially when handled by humans or predators. Young birds, in particular, will freeze and flatten against the ground, hoping their stillness will make them invisible or unappetizing. This instinct can be a last-ditch effort when escape by flight isn’t an option, demonstrating how widespread and diverse thanatosis can be.

Fish That Fake Their Demise

In the watery world, some fish have taken the art of playing dead to new depths. The cichlid fish, for instance, will sometimes lie motionless at the bottom of a tank or riverbed, fooling both predators and rivals. In some cases, this behavior is also used to lure in curious prey—when an unsuspecting fish comes close to investigate, the “dead” cichlid springs to life and strikes. It’s a clever blend of defense and offense in one slippery package.

Amphibians: Frogs and Toads Join the Act

Frogs and toads might seem like easy meals, but many have a theatrical trick up their sleeve. When grabbed by a predator, some species will go limp and appear lifeless, sometimes even rolling onto their backs with legs splayed. This performance can be so convincing that predators lose interest, releasing their grip and allowing the amphibian to make a daring getaway. In some cases, frogs also secrete toxins when playing dead, adding an extra layer of deterrence.

Why Predators Fall for the Ruse

It might seem strange that predators are so easily fooled, but there are reasons behind this. Many predators instinctively avoid dead or dying animals because of the risk of disease or spoilage. For some, the lack of struggle simply makes the prey less appealing or not worth the effort. Over time, this has created a kind of evolutionary arms race—prey get better at acting, while predators get better at seeing through the charade, but the tactic continues to work in many situations.

The Science Behind the Freeze: What Happens in the Brain?

Thanatosis isn’t just a conscious decision; it’s often a reflex controlled by the animal’s nervous system. When faced with extreme threat, the brain triggers a cascade of chemicals that shut down movement and awareness, almost like flipping a switch. Scientists have compared this to the “freeze” response in humans—a deep, involuntary reaction that’s hard to override. Some researchers believe this state may also help the animal cope with pain and trauma during an attack.

From Instinct to Evolution: How the Trait Develops

Not all animals are born actors. Thanatosis is more common in species that face specific predators who lose interest in lifeless prey. Over generations, individuals who were better at playing dead survived longer and passed on their genes. This gradual process of natural selection has fine-tuned the behavior, turning it from a simple freeze into a convincing and elaborate act. It’s evolution’s version of survival by stagecraft.

Risks and Downsides: When Playing Dead Backfires

While thanatosis can save lives, it’s not without risks. If the predator isn’t fooled, the animal is left defenseless and vulnerable. Some scavengers are actually attracted to dead animals, making thanatosis a dangerous gamble in certain situations. And sometimes, animals “wake up” too soon and give themselves away. It’s a high-stakes performance, with no guarantee of applause—or survival.

Beyond Fear: Thanatosis in Social and Mating Contexts

Surprisingly, playing dead isn’t always about avoiding predators. In some species, thanatosis pops up in unexpected places—like mating rituals or social disputes. Certain male spiders will fake death to avoid aggressive females, only to spring back to life when it’s safe to mate. Other animals may use the tactic to avoid confrontation with rivals or to escape tricky situations without fighting.

Human Encounters: What to Do When You See Thanatosis

If you come across an animal that appears dead but then miraculously revives, you’ve likely witnessed thanatosis in action. It’s important not to disturb these creatures, as the stress can be harmful. Give them space and time to recover, and remember that you’ve just seen one of nature’s most remarkable survival stories unfold before your eyes. It’s a powerful reminder of the complex strategies animals use to stay alive.

Thanatosis in Popular Culture and Folklore

The idea of “playing dead” has fascinated people for centuries. From old tales of battlefield trickery to modern movies featuring clever animals, thanatosis has inspired stories, idioms, and even magic tricks. The humble opossum, in particular, has become a symbol of feigned death, popping up in cartoons and jokes. This real-life behavior has woven itself into our collective imagination, blurring the lines between fact and fiction.

Other Odd Survival Tactics: How Thanatosis Compares

While playing dead is remarkable, it’s just one tool in the animal kingdom’s survival toolkit. Other creatures rely on camouflage, mimicry, or explosive escapes. Cuttlefish, for example, change color in an instant, while lizards can detach their tails to escape. Thanatosis, however, stands out because of its sheer audacity—it’s not about hiding, but about boldly pretending the worst has already happened.

Why Don’t All Animals Play Dead?

You might wonder why every animal doesn’t use this trick. The answer lies in the unique challenges and predators each species faces. Thanatosis works best in environments where predators are likely to be deterred by lifeless prey. For animals hunted by creatures that eat anything, dead or alive, this strategy just isn’t worth the risk. Evolution shapes each species’ defenses to fit their particular threats and habitats.

The Future of Thanatosis: Will It Stick Around?

As environments change and predators adapt, the effectiveness of thanatosis may shift too. Some predators are learning to see through the act, forcing prey to get even better at faking it. Meanwhile, human activities are introducing new dangers and opportunities. Scientists continue to study how these changes are influencing survival strategies—not just for the animals, but for the balance of entire ecosystems.

Witnessing Thanatosis: A Personal Perspective

I’ll never forget the first time I saw a snake flip onto its back and play dead right in front of me. For a moment, I thought I’d witnessed something tragic. Then, with a flick of its tail, it sprang back to life and slithered away, leaving me both relieved and amazed. Experiences like this make you realize how much drama and ingenuity unfold in the wild, often right under our noses.

Lessons from the Animal Kingdom

Thanatosis teaches us that survival isn’t always about strength or speed—sometimes, it’s about cleverness and timing. It’s a strange, theatrical reminder that life in the wild is full of surprises. The next time you hear the phrase “playing possum,” remember there’s real science and strategy behind the act. In a world where every day can mean life or death, animals have learned to turn the ultimate defeat into an unexpected victory.