Imagine walking through a golden savanna at sunrise, the air buzzing with life—only to see a majestic lion’s head mounted on a wall thousands of miles away. Few issues in wildlife conservation spark such heated debate as trophy hunting, especially when the targets are endangered species. Is it a necessary evil that helps save animals, or a deeply flawed myth that threatens their very existence? With emotions high and facts often tangled, it’s time to unravel the complex truth behind conservation hunting. Prepare to dive into a world where money, morals, and the fate of the planet’s most iconic creatures all collide.

What Exactly Is Trophy Hunting?

Trophy hunting isn’t just about taking down the biggest animal for bragging rights. At its core, it involves paying large sums of money to hunt wild animals, often with the goal of collecting a trophy—like a horn, head, or skin. The practice is especially controversial when it targets species that are already rare or endangered. Unlike subsistence hunting, which is about survival, trophy hunting is driven by sport and status. Some hunters travel across continents, drawn by the promise of adventure and exclusivity. The animals hunted can range from antelopes to elephants, but it’s the stories about lions, rhinos, and leopards that really catch the public’s attention. The price tags attached to these hunts can be staggering—sometimes costing more than a new car or even a house.

The Origins of Conservation Hunting

Conservation hunting didn’t start as a plan to save wildlife. In fact, its roots are tangled in colonial history, when wealthy foreigners traveled to Africa to hunt big game for sport. Over time, as animal populations started to dwindle, some countries began to regulate hunting and use the profits to fund conservation. This approach promised a win-win: hunters get their trophies, and local communities or governments get money to protect species and habitats. The idea is simple in theory—if animals are valuable alive, people are more likely to protect them and their habitats. However, the reality is far more complicated, often leading to fierce arguments among conservationists, hunters, and animal rights activists.

The Economic Argument: Money Talks

Supporters of trophy hunting often point to the huge sums of money it generates. A single elephant hunt can fetch tens of thousands of dollars, with much of the revenue supposedly going to local communities and conservation projects. In countries with limited resources, this income can be significant. For example, hunting income has funded anti-poaching patrols, habitat restoration, and health clinics in some African regions. The logic is that if wildlife brings in money, people will protect it rather than exploit it for short-term gain. Yet, critics argue that the economic benefits are often overstated or poorly distributed, with much of the profit ending up in the hands of foreign operators or corrupt officials.

Does Trophy Hunting Really Help Conservation?

This is where the debate gets heated. Some scientific studies suggest that well-managed trophy hunting can help populations of certain species recover or stabilize. By setting strict quotas and protecting prime breeding stock, these programs can funnel money into conservation while preventing overhunting. Namibia and Zimbabwe are often cited as success stories, with trophy hunting helping to boost the numbers of certain species like black rhinos and elephants. However, the evidence isn’t always clear-cut. Poorly managed hunts, illegal poaching masked as legal hunting, and corruption can wipe out any potential benefits. There are also cases where trophy hunting has led to dramatic declines in animal populations, especially when regulations are weak or ignored.

The Ethics of Killing to Save

Can killing a few animals really save the rest? This ethical paradox is at the heart of the trophy hunting debate. Supporters argue that sacrificing a small number of old or non-breeding animals—who may die soon anyway—can provide the funds needed to protect whole populations. Opponents say that it sends the wrong message: that animals are worth more dead than alive. The emotional impact of seeing a photo of a hunter next to a dead lion or rhino is powerful, often fueling outrage and calls for bans. For many people, the idea of paying to kill an endangered animal is simply unacceptable, no matter the supposed benefits. The question remains deeply personal and divisive.

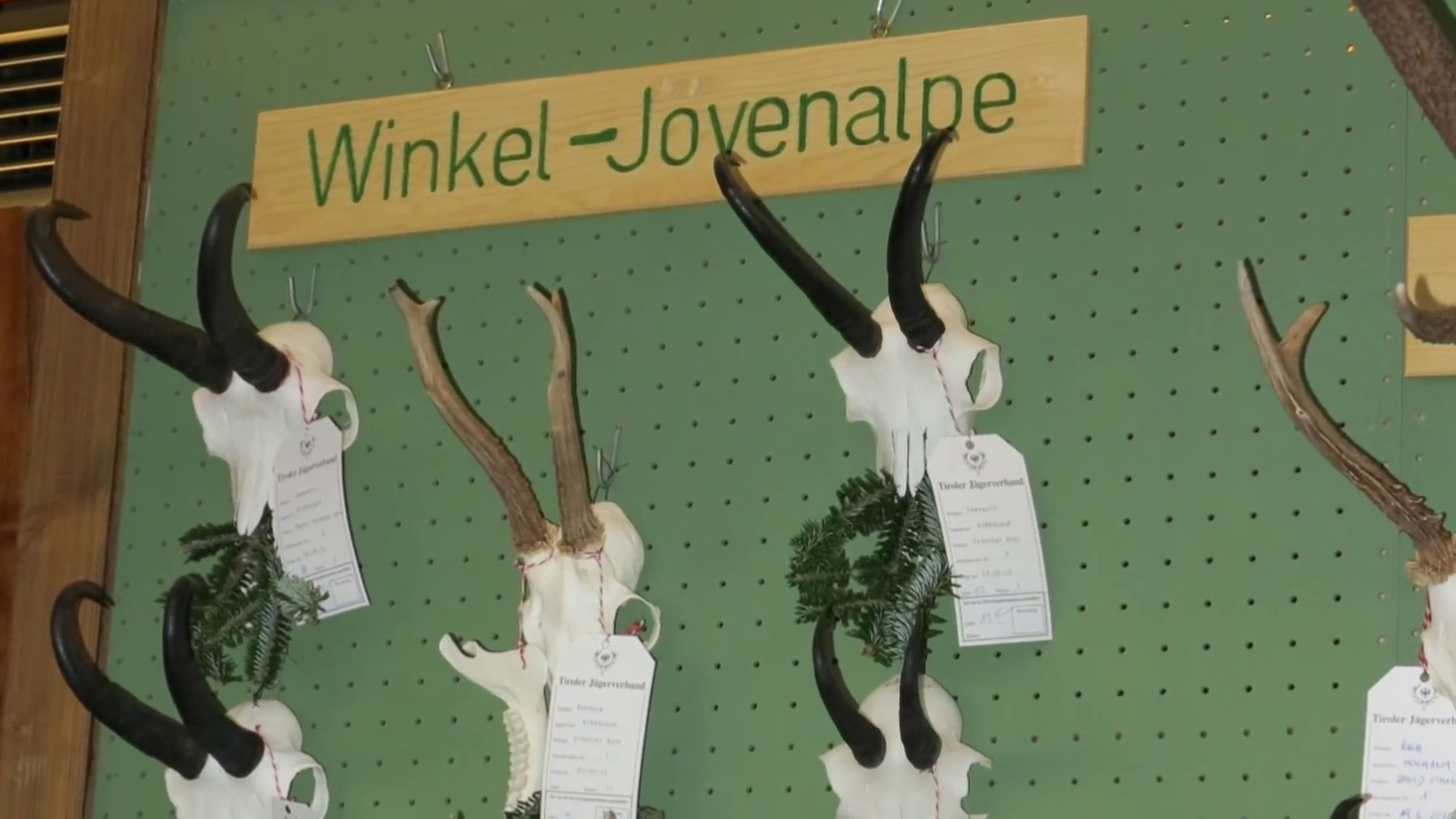

Species in the Crosshairs: Who Gets Hunted?

Not all species are equally targeted by trophy hunters. Lions, elephants, leopards, rhinos, and buffalo—collectively known as the “Big Five”—are among the most prized trophies. These animals are often the face of African wildlife and are deeply entwined with local cultures and tourism. Sadly, they are also among the most vulnerable to extinction. Other species, such as mountain goats, sheep, and certain antelope, are also hunted in both Africa and North America. The choice of species is shaped by rarity, size, and the challenge of the hunt. The more endangered or impressive the animal, the higher its value as a trophy—and the greater the controversy.

Regulation and Quotas: Science or Guesswork?

The effectiveness of trophy hunting depends heavily on how it’s regulated. In theory, science-based quotas are set to ensure only surplus animals are hunted, leaving healthy breeding populations intact. These quotas are often determined using population surveys, biological data, and input from local communities. When done right, this can help ensure that hunting doesn’t push species closer to extinction. But in reality, quotas are sometimes based on poor data, outdated surveys, or political pressure. In some places, corruption or lack of resources means that rules are ignored or bent, leading to overhunting and population crashes.

Local Communities: Stakeholders or Bystanders?

One of the main arguments for trophy hunting is that it benefits local communities, giving them a financial stake in wildlife conservation. In some areas, hunting fees have been used to build schools, clinics, and wells, or to compensate villagers for livestock lost to predators. When communities see direct benefits, they are more likely to support conservation and resist poaching. However, there are many cases where promised benefits have failed to materialize, or where most of the money is siphoned off by outside interests. True community involvement requires transparent management, fair sharing of revenue, and a real voice in decision-making.

Poaching vs. Legal Hunting: Drawing the Line

It’s easy to confuse trophy hunting with poaching, but the two are fundamentally different. Poaching is illegal and unsustainable, driven by demand for animal parts like ivory, horns, and skins. Trophy hunting, in theory, is tightly regulated and aims to be sustainable. However, the line can blur when corruption, weak enforcement, or fake permits come into play. Sometimes, legal hunting provides cover for illegal activities, undermining conservation goals. The challenge is ensuring that trophy hunting doesn’t inadvertently fuel poaching or create loopholes for wildlife traffickers.

The Role of International Laws and Treaties

Trophy hunting of endangered species is subject to a web of international laws, including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). These rules are designed to ensure that cross-border trade in animal parts doesn’t threaten wild populations. Permits are required for certain species, and quotas are set at both national and international levels. However, enforcement varies widely, and loopholes can be exploited. Some countries have banned the import of trophies from specific species or regions, adding another layer of complexity. These legal frameworks are constantly evolving as new threats and information emerge.

The Impact on Genetics and Population Health

Trophy hunters often target the biggest and most impressive animals—those with the largest horns, tusks, or manes. Over time, this can have unexpected consequences for the health and genetics of populations. Removing top males may reduce genetic diversity and affect breeding success. Scientists have found that in some species, selective hunting has led to smaller horns or tusks in future generations—a phenomenon known as “unnatural selection.” This raises questions about the long-term impacts of trophy hunting, even when population numbers appear stable.

Ecotourism: A Kinder Alternative?

As public opposition to trophy hunting grows, ecotourism is often promoted as a more ethical and sustainable way to fund conservation. Instead of shooting animals, tourists pay to watch and photograph them in the wild. This can bring in significant revenue, create jobs, and foster local pride in wildlife. In some cases, ecotourism has helped protect entire ecosystems, from African savannas to rainforests. However, it’s not a silver bullet. Ecotourism requires stable infrastructure, political security, and ongoing investment. In remote or politically unstable areas, trophy hunting may still be the only viable source of funding for conservation.

Celebrity Influence and Public Outrage

Every few years, a high-profile trophy hunt sparks international outrage—like the killing of Cecil the lion in Zimbabwe. These moments can galvanize public opinion and lead to calls for bans or stricter regulations. Celebrities, activists, and social media amplify these stories, turning them into viral campaigns. While this can drive change and raise awareness, it can also oversimplify complex issues or lead to knee-jerk policy decisions. The challenge is balancing public emotion with scientific evidence and the needs of local communities.

Case Studies: Successes and Failures

Real-world examples highlight both the promise and pitfalls of conservation hunting. In Namibia, community-based conservancies have used hunting revenues to restore wildlife populations and habitats, with marked increases in some species. Yet in Tanzania, poor management and corruption have led to declines in key species despite years of trophy hunting. In Botswana, a ban on trophy hunting led to increased numbers of certain species, but also to rising human-wildlife conflict as animals roamed into farmland. Each case underscores the importance of context, transparency, and strong governance.

Innovative Solutions for Conservation Funding

With trophy hunting under scrutiny, conservationists are searching for new ways to fund wildlife protection. Carbon credits, wildlife-friendly agriculture, and direct payments for ecosystem services are just a few of the ideas being tested. Some organizations are experimenting with “photographic hunting” experiences, where tourists pay for the thrill of tracking animals without causing harm. The challenge is to find models that are both profitable and sustainable, especially in places where options are limited.

The Science of Measuring Impact

How do we know if trophy hunting really helps or harms wildlife? Scientists use a range of tools, from population surveys to genetic studies and economic analyses. Yet, data can be patchy or unreliable, especially in remote areas. Long-term studies are rare, and results often depend on local context. What works in one country or for one species may fail in another. The ongoing challenge is to gather better data, share results openly, and use science—not just emotion or ideology—to guide decisions.

Voices from the Field: Rangers, Scientists, and Locals

Behind every statistic are real people living and working with wildlife. Rangers risk their lives to protect animals from poachers. Scientists spend years tracking populations and studying behavior. Local villagers may face daily threats from lions, elephants, or leopards, balancing the need for safety with the hope for economic opportunity. Their stories are often lost in the global debate, but they hold the key to finding solutions that work for people and wildlife alike.

What Does the Future Hold?

The future of conservation hunting is anything but certain. As ecosystems face mounting pressures from climate change, habitat loss, and human population growth, the stakes have never been higher. Some countries are tightening regulations or banning trophy hunting altogether, while others defend it as a vital tool for survival. The debate continues to evolve, shaped by new research, changing values, and the voices of those most affected. The question remains: can we find a path that truly protects endangered species while honoring the needs and hopes of people who live alongside them?