The Denisovans, a deeply mysterious branch of the human family tree, have obsessed researchers across the globe for decades. Except for a finger bone discovered in Siberia, some teeth found in Tibet, and strands of DNA found in modern humans, they were virtually unknown. Now, an astonishing discovery in the form of a jawbone found on the seafloor close to Taiwan has been identified as belonging to the Denisovan through advanced protein analysis. This pushes our understanding of these humans further into subtropical East Asia, showing their astonishing range and adaptability from the Siberian mountains to coastal regions. The find reignites debates on the physical appearance of the Denisovans and where they lived, and why their genetic legacy continues to exist in people today.

A Fisherman’s Net and a 100,000-Year-Old Mystery

In 2010, fishermen trawling the Penghu Channel, about 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) off Taiwan’s coast, hauled up an unexpected catch: a fossilized jawbone nestled among ancient elephant and hyena bones. The relic, dubbed Penghu 1, spent years in limbo first sold to an antique shop, then donated to Taiwan’s National Museum of Natural Science. Scientists initially classified it as part of the Homo genus but hit a wall: no DNA could be extracted from the sea-worn bone.

The breakthrough came in 2025, when an international team turned to paleo proteomics, the study of ancient proteins. By analyzing collagen fragments in the teeth, they matched sequences to those of Denisovans from Siberia. “This jawbone is a Rosetta Stone for understanding their physical traits,” said Frido Welker, a co-author of the study published in Science.

The Denisovan Paradox: Genetic Ghosts, Few Fossils

Denisovans were first identified in 2010 through DNA from a pinky finger bone in Siberia’s Denisova Cave. Since then, their genetic footprint has been found in modern populations up to 5% in Melanesians and Tibetans but physical remains are vanishingly rare. Only a handful of fossils are confirmed: a jaw from Tibet, a molar from Laos, and now, Penghu.

This scarcity makes the Taiwan jawbone revolutionary. “It’s like having a fingerprint but no face,” said Chris Stringer of London’s Natural History Museum. The bone’s robust shape and lack of a chin align with other Denisovan remains, but its coastal origin shatters assumptions that they were confined to cold highlands.

Survivors of a Lost World: From Siberia to the Tropics

The jawbone’s discovery hints at a startling truth: Denisovans thrived in wildly diverse environments. The Siberian group endured subzero temperatures, while the Tibetan Denisovans evolved adaptations for high-altitude hypoxia. Now, Penghu 1 suggests they also inhabited warm, humid regions, possibly a land bridge between China and Taiwan during the Pleistocene, when sea levels were lower.

“Denisovans weren’t just cave dwellers, they were explorers,” said archaeologist Zhang Dongju, who studied the Tibetan specimens. Their spread may explain why traces of their DNA appear in Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders today .

The Protein Detective Work That Cracked the Case

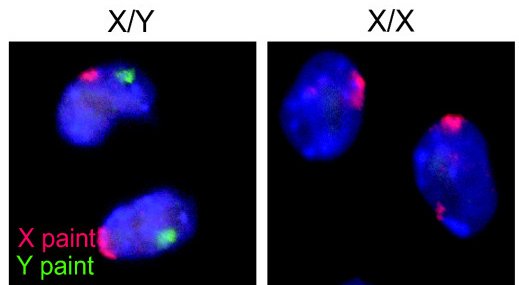

With DNA too degraded for analysis, scientists turned to protein molecules that outlast genetic material. By comparing amino acid sequences from Penghu 1 to those of known Denisovans, they identified a match. Even more intriguing, Y-chromosome peptides revealed the jawbone belonged to a male, offering rare insight into Denisovan biology .

Critics urge caution, noting protein analysis isn’t as precise as DNA. But as Katerina Douka, an archaeologist at the University of Vienna, put it: “When you’re dealing with ghosts, you take what clues you can get” .

Interbreeding and the “Genetic Superpower” Legacy

Denisovans didn’t just vanish, they merged with us. Modern humans carry Denisovan genes linked to immune response, fat metabolism, and even altitude adaptation (a boon for Tibetans). The newly discovered MUC19 gene, found in Indigenous Americans, may have been inherited via Neanderthals who previously interbred with Denisovans a genetic game of telephone spanning millennia.

“This wasn’t a one-night stand, it was a long-term relationship,” quipped Sharon Browning, a geneticist who uncovered evidence of two distinct Denisovan interbreeding events in Asia.

The Hunt for More Denisovans: Hidden in Plain Sight?

The Penghu 1 fossil raises a tantalizing question: How many other Denisovan relics are gathering dust in museums or lying underwater? Taiwan’s National Museum holds 4,000 seabed fossils, some of which could be Denisovan. Meanwhile, researchers are re-examining controversial specimens like China’s “Dragon Man” skull, which shares traits with Denisovans.

As Chun-Hsiang Chang, a curator in Taiwan, mused: “There’s treasure in these collections. We just need the tools to find it” .

Conclusion: A Species Defined by Its Ghosts

The Taiwan jawbone confirms Denisovans as master adapters occupying deserts, mountains, and now coastlines. Yet their story remains half-told. Were they a single species or multiple populations? Did they speak, create art, or bury their dead? Each fossil chips away at the mystery, proving that even in extinction, the Denisovans refuse to be forgotten.

“They’re the ultimate survivors,” says Welker. “Not in flesh, but in us.”

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.