Imagine a land where birds outnumber mammals, where ancient forests echo with strange, haunting calls, and where some of the world’s oddest creatures have wandered for millions of years. New Zealand is a place like no other—a lost world where the rules of evolution seem to have been rewritten. But why, out of all places on Earth, did so many birds here trade their wings for sturdy legs? Dive into the wild heart of Aotearoa, where the ground is alive with the gentle shuffles of flightless birds, and discover the secrets that grounded these remarkable creatures.

The Great Isolation: New Zealand’s Unique Evolutionary Playground

New Zealand’s story begins with its isolation. Millions of years ago, the land split from the supercontinent Gondwana and drifted into the vast Pacific, far from other landmasses. With no native land mammals (except for a few bats), birds took center stage in nearly every ecosystem. Here, they faced little competition or threats from predatory mammals, giving them the freedom to experiment with new ways of life. Over time, this geographical solitude became the perfect laboratory for evolutionary oddities, especially birds that found no need to fly.

The Kiwi: A National Icon with Ancient Roots

The kiwi is perhaps New Zealand’s most beloved bird, instantly recognizable for its long beak and shaggy, hair-like feathers. Unlike most birds, kiwis lay gigantic eggs compared to their body size—a true marvel of nature. Their nostrils are at the tip of their beak, a feature that helps them sniff out insects and worms in the dark forest floor. Because there were no ground predators for millions of years, kiwis lost their ability to fly and became expert foragers on foot. Today, seeing a kiwi in the wild is like gazing into the past—a living link to ancient New Zealand.

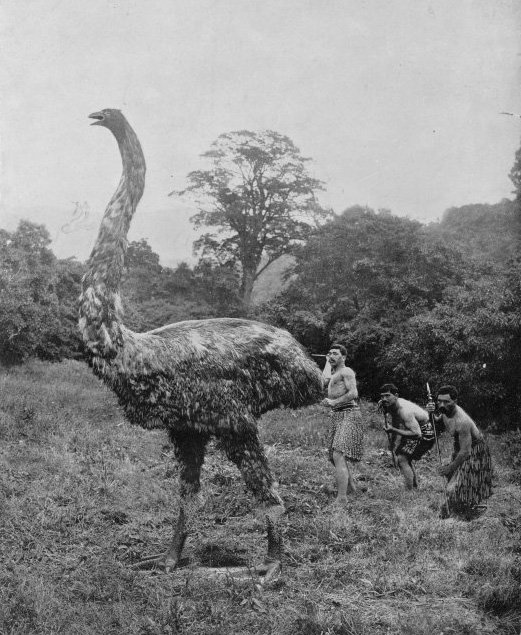

The Mighty Moa: Giants That Once Ruled the Land

Before humans arrived, enormous moa birds roamed the forests and grasslands. Some species stood over three meters tall, towering above even the tallest humans. Moas had powerful legs and no wings at all—just tiny vestiges hidden under their feathers. They browsed on leaves, twigs, and fruits, shaping the landscape as they wandered. Sadly, these gentle giants vanished only a few hundred years ago, hunted to extinction by the first Polynesian settlers. Their bones and eggshells, found scattered across the countryside, are silent reminders of what once was.

The Curious Case of the Kakapo: The World’s Only Nocturnal Parrot

The kakapo is a feathered oddball—a parrot that can’t fly and only comes out at night. With its round body, mossy-green feathers, and owl-like face, the kakapo blends perfectly with New Zealand’s forests. Instead of soaring through the treetops, it waddles along the ground, using its wings for balance as it climbs trees. Kakapos evolved without fear of ground predators, but this has made them tragically vulnerable to introduced animals like cats and stoats. Today, every single kakapo has a name and a team of dedicated humans fighting for its survival.

The Takahē: Rediscovered Against All Odds

The takahē was once thought extinct—lost to history like the moa. But in 1948, a small group was miraculously rediscovered in a remote mountain valley. These chunky, blue-green birds have strong legs and bright red beaks, and they spend their days munching on tussock grass. With stubby wings and a hefty build, flying simply isn’t an option. Their story is one of hope and resilience, as scientists and conservationists work around the clock to protect their fragile population.

Why Did So Many Birds Lose the Ability to Fly?

Flight is energy-intensive. In New Zealand’s safe, mammal-free world, the costs of maintaining flight muscles and light bones outweighed the benefits. Ground-dwelling birds could grow larger and more powerful, better equipped to forage and survive in dense forests or open grasslands. Evolution favored those who put their resources into walking, running, or burrowing, rather than flying. Over countless generations, wings shrank, breastbones flattened, and the skies grew quieter.

The Absence of Mammalian Predators: A Recipe for Grounded Birds

For millions of years, New Zealand’s birds faced almost no threat from land predators. There were no foxes, no wolves, not even snakes. The only native mammals were bats, which posed no danger to birds. This safe haven allowed birds to nest and feed on the ground, free from the constant fear of attack. It’s hard to imagine such a peaceful Eden today, but that’s exactly the world these birds evolved in—until humans and their animals arrived.

The Arrival of Humans: A Turning Point for Flightless Birds

When Polynesians first set foot in New Zealand around 700 years ago, everything changed. With them came dogs and rats, soon followed by European settlers bringing cats, stoats, and more. Flightless birds, unaccustomed to such threats, fell easy prey. Moas disappeared within a few centuries. Kiwis, takahē, and kakapos saw their numbers plummet. The arrival of humans was a shock to the system, upending millions of years of peaceful evolution in a matter of generations.

Survival Strategies: How Some Birds Adapted

Not every flightless bird succumbed to extinction. Some, like the kiwi, adapted by becoming even more secretive and nocturnal, hiding in dense forests during the day. Others found refuge on predator-free islands or remote mountain valleys. Conservationists have stepped in to create “island sanctuaries” where vulnerable birds can live safely, away from introduced threats. These modern efforts echo nature’s own solutions—finding safety in numbers, inaccessibility, or the cover of darkness.

The Weka: The Mischievous Scavenger

The weka is a small, sturdy bird with a personality much bigger than its body. Known for its curiosity and cheeky behavior, the weka loves to steal shiny objects and rummage through campsites. Unlike some of its flightless cousins, the weka has managed to survive by being bold and adaptable. It eats almost anything—bugs, berries, even small animals. But this adaptability is a double-edged sword, as weka sometimes prey on the eggs of other native birds, creating a complex web of survival.

The Evolutionary Trade-Off: Bigger Bodies, Stronger Legs

Losing flight opened up new evolutionary paths for New Zealand’s birds. Without the weight restrictions of flying, species like the moa grew massive, reaching sizes rivaling small dinosaurs. Others, like the takahē, developed incredibly strong legs for climbing hills and digging for food. Larger bodies helped them withstand the cold, store energy, and defend their territories. This trade-off—flight for strength—was a gamble that paid off, at least until predators arrived.

Strange Beaks and Unique Diets

Flightless birds in New Zealand evolved some truly bizarre beaks to match their unusual lifestyles. The kiwi’s long, flexible bill is perfect for probing the soil, while the takahē’s powerful beak crushes tough grasses. Moas had beaks shaped for nibbling leaves high up in the forest. The kakapo’s beak is almost parrot-like, able to strip bark and dig for roots. Each beak tells a story of adaptation—a tool honed by countless generations to exploit a specific niche in a land of opportunity.

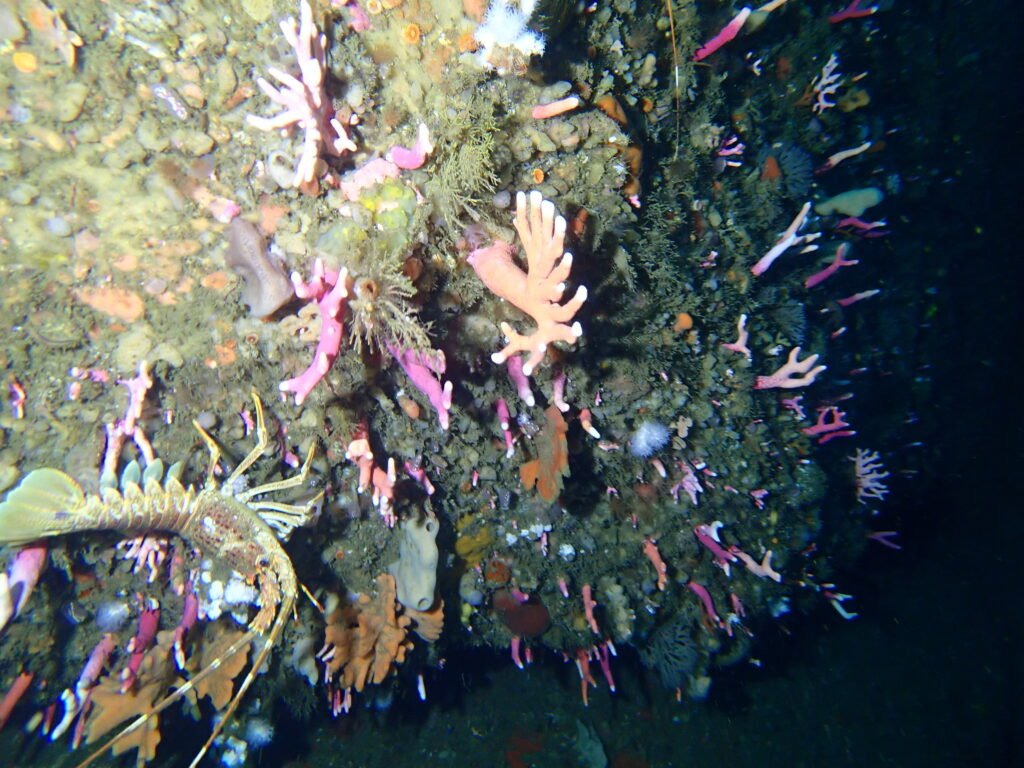

The Role of Forests and Mountains

New Zealand’s diverse landscapes shaped the evolution of its flightless birds. Dense rainforests provided cover for secretive species like the kiwi and kakapo. Open tussock grasslands were home to the takahē, while moas roamed everywhere from coastal dunes to alpine slopes. Rugged mountains and remote valleys became refuges from human and animal invaders. The country’s varied habitats offered endless possibilities for birds willing to give up flight and explore the world on foot.

Eggs, Nests, and Parenting: Ground Rules

With no need to build nests high in trees, many flightless birds laid their eggs on the ground. Kiwi eggs are among the largest in relation to body size, packed with nutrients to give chicks a head start. Kakapos dig burrows or hide their eggs among roots, while takahē build grassy mounds in the open. Parenting styles evolved, too—male kiwis often incubate the eggs, while kakapos leave chicks to fend for themselves. These adaptations helped ground-nesting birds thrive in a land without tree-climbing predators.

Vulnerability and Conservation: Walking the Edge

Today, most of New Zealand’s flightless birds are teetering on the brink of extinction. Their slow reproductive rates, specialized diets, and inability to escape predators make them deeply vulnerable. Conservationists have gone to extraordinary lengths to save them, from hand-rearing chicks to relocating entire populations to safe islands. Each bird rescued is a small victory against the tide of extinction, but the battle is far from over.

Flightless Birds in Māori Culture and Myth

Flightless birds hold a special place in Māori culture. The kiwi is a symbol of New Zealand identity and pride, while moas feature in ancient legends as fearsome forest giants. Kakapos and wekas also appear in traditional stories and carvings, representing resilience, cunning, or even foolishness. These birds are more than just animals—they are woven into the very fabric of the land, linking past and present in a shared heritage.

Lessons from Extinction: What the Moa Taught Us

The loss of the moa was a wake-up call for New Zealand and the world. It showed how quickly a unique species could vanish when faced with new threats. Scientists study moa bones and DNA to understand how these giants lived and why they disappeared. Their extinction has inspired a new generation of conservationists, determined to prevent the same fate from befalling other flightless birds. The lessons learned are sobering, but they offer hope for the future.

Modern Science and the Quest for Survival

Researchers are using cutting-edge tools—like genetics, tracking devices, and smart sensors—to better understand and protect flightless birds. By studying their movements, diets, and diseases, scientists can fine-tune conservation efforts and predict future risks. Breeding programs are helping boost numbers, while predator-proof fences and sanctuaries offer safe havens. Technology is giving these ancient birds a fighting chance in a modern world.

A Living Laboratory: What Flightless Birds Teach Us About Evolution

New Zealand’s flightless birds are more than just curiosities—they are living experiments in evolution. They reveal how quickly nature can adapt to new environments, and how fragile those adaptations can be. By studying their bones, behaviors, and genetics, scientists unravel the mysteries of speciation, adaptation, and extinction. Their stories remind us that evolution is always at work, hidden in the quiet shuffle of feet across the forest floor.

Guardians of the Ground: The Human Role in Their Future

Today, the fate of these birds rests in human hands. Volunteers, scientists, and communities across New Zealand are working together to restore habitats, remove predators, and educate the public. Schoolchildren grow up learning about kiwis and kakapos, while tourists travel from around the world to catch a glimpse of these living treasures. Every effort counts, and every saved bird is a testament to what people can achieve when they care deeply.

The Magic of a World Without Flight

There’s something enchanting about a land where birds walk instead of fly—where evolution took an unexpected detour and created creatures unlike any others. New Zealand’s flightless birds invite us to slow down, look closer, and appreciate the beauty of adaptation. Their presence is a gentle reminder that sometimes, the most extraordinary stories unfold not in the sky, but right beneath our feet.