For over a century, the fossil record pinned the rise of reptiles to around 320 million years ago, during the late Carboniferous period. But a serendipitous discovery in the rugged outcrops of southeastern Australia has thrown that timeline into chaos. A set of clawed footprints, preserved in a slab of rock no larger than a suitcase, suggests reptiles may have been prowling ancient landscapes a staggering 30 to 40 million years earlier than previously believed pushing their origins back into the mid-Devonian period, an era better known for fish-like tetrapods hauling themselves onto primordial shores.

Published in Nature, the study has sent shockwaves through paleontology, forcing scientists to reconsider not just when reptiles evolved, but how quickly life transitioned from water to land.

The Footprint That Shattered the Timeline

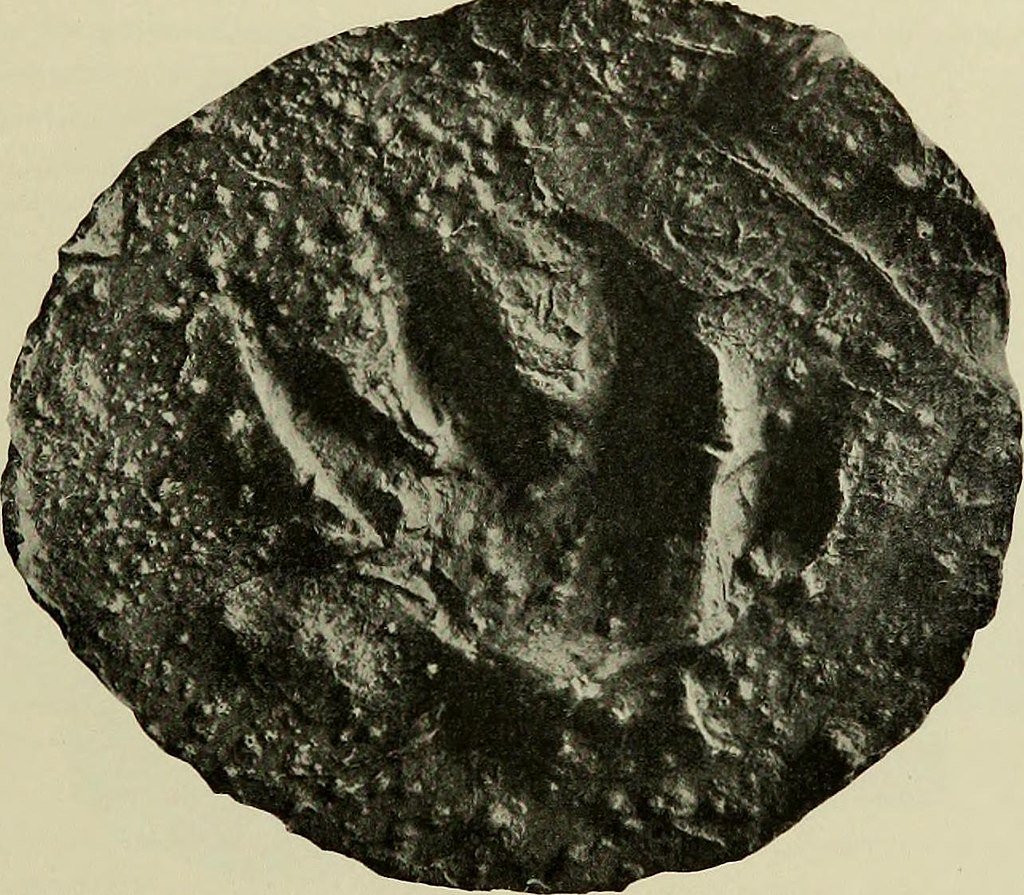

The story begins with two amateur fossil hunters scouring the Snowy Plains Formation in Victoria, Australia. Their find? A 20-inch (50 cm) sandstone slab etched with a series of faint, claw-tipped impressions. At first glance, they might have been dismissed as mere scratches but closer inspection revealed something extraordinary.

These weren’t the rounded toe pads of early amphibians. They were narrow, elongated tracks with sharp claw marks, a telltale signature of amniotes the group that includes reptiles, birds, and mammals. The rock layer dated back 350 million years, placing these prints deep in the Carboniferous period, long before confirmed reptile fossils appear in the record.

“Once we identified this, we realized this is the oldest evidence in the world of reptile-like animals walking around on land,” says Dr. John Long, a paleontologist at Flinders University and co-author of the study.

Why Claws Change Everything

Claws are a smoking gun in evolutionary biology.

- Amphibians of this era, like Ichthyostega, had stubby, paddle-like feet for navigating swamps.

- Early amniotes, by contrast, evolved claws for digging, climbing, or grasping prey adaptations for a fully terrestrial life.

“Claws are present in all early amniotes, but almost never in other groups of tetrapods,” explains Dr. Per Ahlberg, a paleontologist at Uppsala University and study co-author. “The combination of claw scratches and foot shape suggests this was a primitive reptile.”

If confirmed, this means reptiles were already established while their amphibian cousins were still wrestling with life on land.

The Amniote Revolution: Breaking Free From Water

What made reptiles (and their amniote kin) so revolutionary? The egg.

- Amphibians relied on water to reproduce, laying jelly-coated eggs vulnerable to drying out.

- Amniotes developed a self-contained, hard-shelled egg with a protective membrane (amnion), allowing them to colonize dry environments.

Previously, the oldest amniote fossils (like Hylonomus) dated to 312 million years ago. But these new tracks suggest amniotes were already diversifying 50 million years earlier right on the heels of the first land vertebrates.

“This single slab calls into question everything we thought we knew about when modern tetrapods evolved,” says Ahlberg.

A Ghost Lineage Lurking in the Shadows

If reptiles existed 350 million years ago, why haven’t we found their bones?

The answer may lie in preservation bias.

- The Devonian and early Carboniferous were dominated by vast, swampy wetlands.

- Reptiles, being more terrestrial, may have lived in upland environments where fossils rarely form.

“It’s like finding a single page of a lost book,” says Dr. Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki, another co-author. “We know the story is incomplete.”

Genetic studies support this: DNA-based evolutionary trees suggest amniotes should have appeared earlier than the fossil record showed until now.

Did Reptiles Walk With Tiktaalik’s Descendants?

The Devonian period (419–359 million years ago) was the age of fish with feet creatures like Tiktaalik and Acanthostega, which bridged the gap between fins and limbs.

But these new tracks imply that while some vertebrates were still figuring out walking, others had already evolved into true land-dwelling reptiles.

“It’s all about the relative length of branches in the evolutionary tree,” says Ahlberg. “This discovery stretches one of those branches much further back.”

What’s Next? The Hunt for More Hidden Clues

The team is now scouring other 350-million-year-old rock formations for more evidence.

- Could there be skeletal fossils of these early reptiles waiting to be found?

- Did they coexist with giant arthropods like Arthropleura, the 6-foot-long millipede?

“The most interesting discoveries are yet to come,” says Niedźwiedzki. “These footprints are just the beginning.”

One thing is certain: the history of reptile evolution just got a lot more complicated.

Final Thought

Science lives on breakthrough discoveries and this one is a bombshell. If proven, it means:

- Reptiles emerged 30–40 million years earlier than believed.

- The process of transition from water to land was quicker and more complicated than we had envisioned.

- There’s a ghost chapter in evolutionary history still waiting to be uncovered.

As Long puts it: “Every major discovery like this forces us to rethink what we know. And that’s what makes paleontology so thrilling.”

What other secrets are buried in the rocks? Only time and a few more lucky fossil hunters will tell.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.