Imagine a world where birds the size of horses roamed shadowy forests, and the sky above held the most ferocious raptor ever known. New Zealand’s ancient wilderness was once home to a dramatic struggle between two giants: the flightless moa and the awe-inspiring Haast’s eagle. Their story isn’t just a tale of predator and prey. It’s a vivid portrait of evolution, extinction, and the wild power of nature that once thrived in isolation. As we peel back the layers of this primeval drama, you’ll discover a world so strange and compelling, it almost feels like myth—except, every word is grounded in scientific wonder.

The Isolated Eden: New Zealand’s Lost World

New Zealand was cut off from the rest of the world for millions of years, a secret garden where evolution ran wild. Without mammals to dominate the land, birds grew into incredible forms and sizes, filling every niche. The absence of big land predators meant that some birds, like the moa, lost the ability to fly and grew enormous. This isolation set the stage for unique evolutionary experiments, leading to the rise of giants and monsters that could have stepped right from the pages of a fantasy novel. The forests were thick, the undergrowth lush, and the air alive with the calls of strange animals. It was a world shaped by its own rules, where the unexpected was just everyday life.

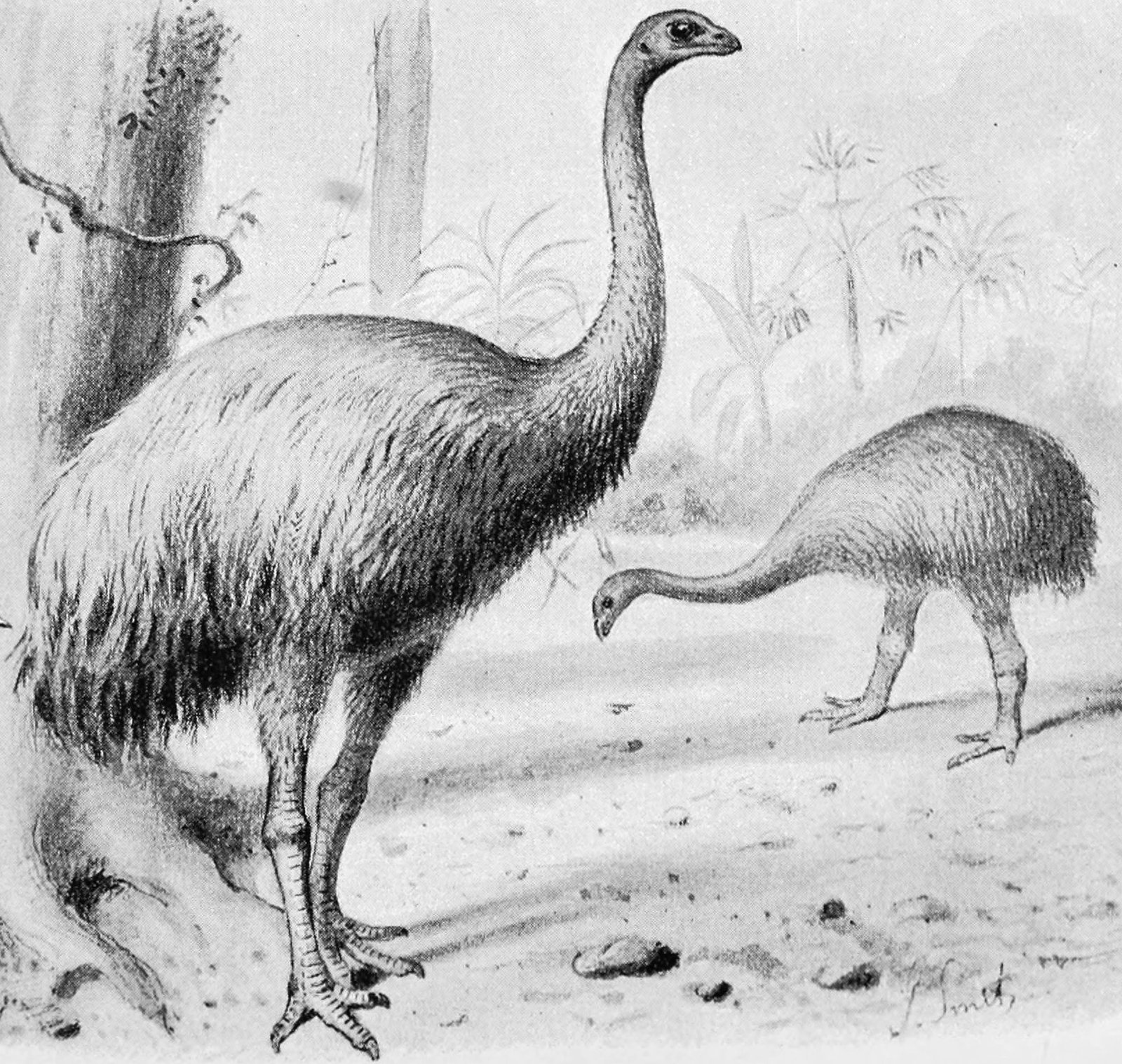

Moa: The Gentle Giants of the Forest

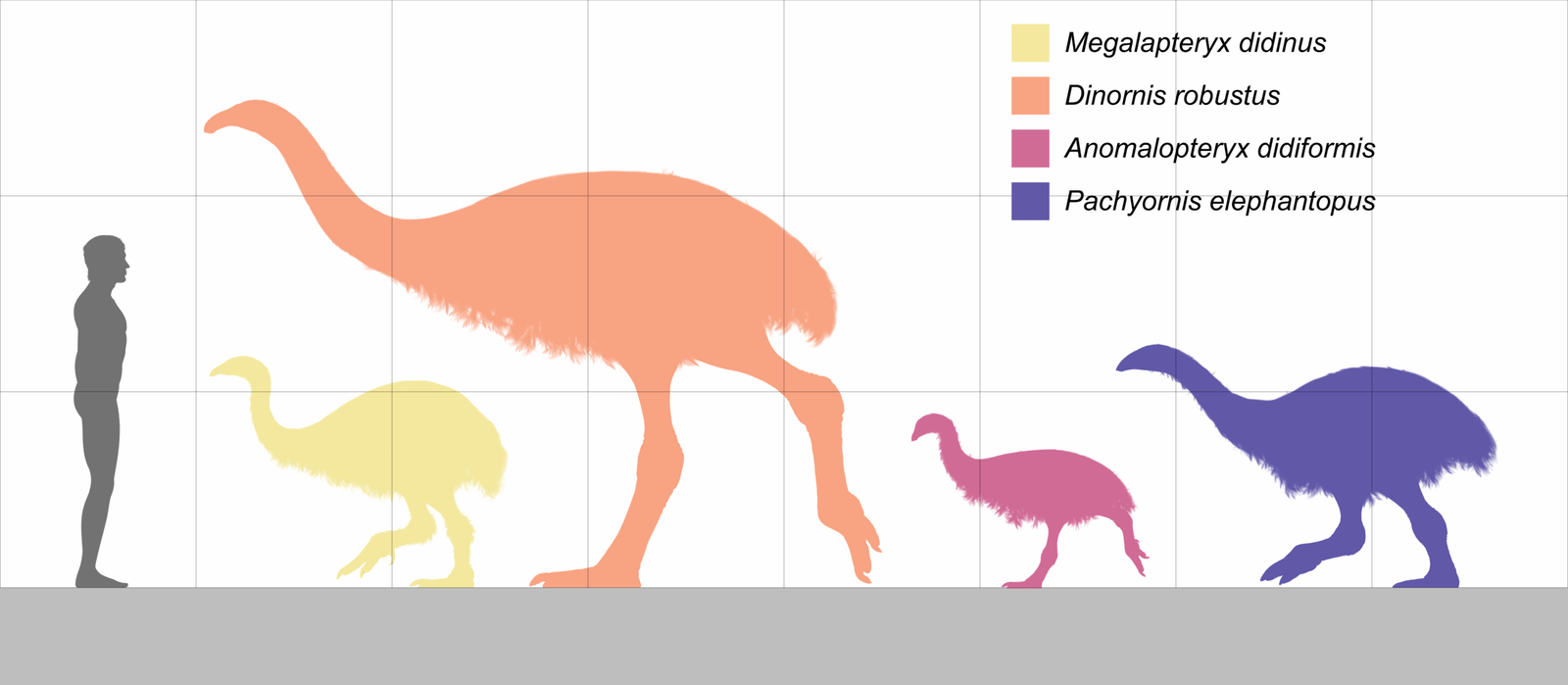

Moa were the undisputed giants of New Zealand’s forests. Some stood over three meters tall, towering above the ferns and low trees. Despite their massive size, these birds were gentle herbivores, quietly browsing on leaves, twigs, and fruit. Their long necks allowed them to reach high vegetation, much like giraffes on a distant continent. Moa moved in loose groups, their heavy footsteps echoing softly through the mossy undergrowth. Unlike ostriches, their closest living relatives, moa had no wings at all—not even tiny ones. Their legs were sturdy, built for walking rather than running, and their large bodies made them slow but steady travelers through the dense bush.

Haast’s Eagle: The Apex Predator in the Sky

If the moa were the kings of the ground, then Haast’s eagle ruled the sky with terrifying authority. With a wingspan up to three meters and talons as large as a tiger’s claws, this eagle was the largest and most powerful raptor ever to exist. It was built for ambush, using its sharp eyesight to spot prey from above. When it attacked, it would dive with astonishing speed, striking with enough force to break bones in an instant. Haast’s eagle didn’t just hunt moa—it depended on them. The relationship between these two species would shape both their destinies, binding them in a deadly dance that would last thousands of years.

Evolutionary Oddities: How Giants Came to Be

The story of how moa and Haast’s eagle grew so large is a fascinating chapter in evolutionary biology. In the absence of mammals, birds filled every available ecological role. Moa evolved to become grazing “browsers,” taking over the job of large plant-eaters. Meanwhile, Haast’s eagle ballooned in size to fill the predator gap left by the missing carnivorous mammals. This process is called island gigantism, a phenomenon seen in other isolated places but nowhere as dramatically as in New Zealand. The evolutionary arms race pushed both species to extremes, turning the peaceful forests into a theater of natural selection on a grand scale.

A Predator’s Arsenal: The Hunting Tactics of Haast’s Eagle

Haast’s eagle was a master of surprise. Using the thick forest canopy as cover, it would wait above game trails, watching for the slow-moving moa below. The eagle’s immense talons could grip with a force strong enough to pierce bone and muscle. When a target was spotted, the eagle would launch itself downward in a rapid, controlled dive, aiming for the neck or back. The initial impact alone could knock a moa off its feet. After a successful strike, the eagle would use its powerful beak to tear through tough feathers and skin. This predatory efficiency made Haast’s eagle both feared and respected in the animal kingdom.

The Moa’s Defense: Adaptation or Vulnerability?

Despite their size, moa were not built for defense. They had no natural weapons—no horns, claws, or sharp beaks. Their main strategy was to blend in with the forest, relying on their brownish feathers for camouflage among tree trunks and leaf litter. Some scientists believe that their height allowed them to spot danger from a distance, but the dense bush would have limited visibility. Mothers likely kept their chicks close, using their bulk as a shield. But against a determined Haast’s eagle, these defenses often proved inadequate. In many ways, the very adaptations that helped moa thrive—gigantism and flightlessness—also became their greatest vulnerabilities.

Life in the Shadows: The Daily Struggles of Moa

Every day was a quiet battle for survival in the ancient forests. Moa had to find enough food to sustain their weight, which meant hours of constant foraging. Their size made them slow and conspicuous, especially to a hungry Haast’s eagle lurking above. Chicks and juveniles were particularly at risk, often falling prey before reaching full size. Moa moved in groups, perhaps as a way to reduce individual risk—there’s safety in numbers, even for giants. The constant threat of predation shaped their behavior and even influenced their reproductive strategies, as they laid large eggs in well-hidden nests to increase the odds of survival.

Haast’s Eagle’s Diet: More Than Just Moa

While moa were the primary prey, Haast’s eagle was an opportunistic hunter. It also targeted other large birds, such as the flightless goose-like adzebill and giant rails. Occasionally, it might have scavenged on carrion or preyed on smaller animals if larger game was scarce. However, the sheer size of Haast’s eagle meant it needed a steady supply of substantial meals—making the extinction of moa a death sentence for the eagle itself. This tight dependency highlights the fragile balance in such a specialized ecosystem, where the fate of one species could spell disaster for another.

Fossils in the Mist: Uncovering Ancient Clues

Much of what we know about these lost titans comes from fossils found in caves, swamps, and riverbeds. Moa bones are often discovered in large numbers, sometimes with eggshell fragments nearby, painting a picture of their nesting habits. Haast’s eagle remains are rarer, but include skulls with massive beaks and talons still sharp after centuries in the earth. Some moa bones even show damage consistent with eagle attacks—a chilling echo of ancient battles. These fossils are like puzzle pieces, helping scientists reconstruct the drama that unfolded in New Zealand’s prehistoric forests.

Human Arrival: The Beginning of the End

When Polynesian settlers arrived in New Zealand around 700 years ago, everything changed almost overnight. Moa, unaccustomed to mammalian predators, were easy targets for hunters. Their large size and slow reproduction rates made them especially vulnerable. Forests were burned to create farmland, destroying vital habitat. Within a few generations, all nine species of moa were extinct. Haast’s eagle, robbed of its primary food source, soon followed. The end came swiftly, a tragic reminder of how even the mightiest creatures can vanish in the blink of an eye.

Scientific Sleuths: Reconstructing the Past

Modern scientists are like detectives, piecing together the lives of moa and Haast’s eagle from scattered clues. Ancient DNA extracted from bones helps reveal relationships between species, while isotopic analysis of feathers and eggshells provides insight into diet and migration patterns. Computer models simulate eagle attacks, showing just how powerful these birds really were. Even indigenous Maori legends, which speak of giant birds swooping from above, offer tantalizing hints about these vanished giants. Every discovery adds depth to our understanding of a world lost to time.

Legends and Lore: The Giants in Maori Culture

For the Maori, moa and Haast’s eagle were more than just animals—they were woven into the fabric of myth and legend. Stories tell of gigantic birds called “Pouakai” that could snatch people from the ground, a possible memory of encounters with Haast’s eagle. Moa bones were used as tools and ornaments, and their disappearance marked a deep cultural shift. These tales keep the memory of the lost giants alive, reminding us that science and storytelling are often intertwined. The echoes of these creatures still linger in the landscape, haunting the mountains and forests they once called home.

A World Without Mammals: The Strange Balance

The absence of native land mammals (except for bats) created a biological playground unlike anywhere else. Birds filled the roles of grazers, predators, and even scavengers. Moa browsed the forests like deer, while Haast’s eagle hunted with the skill and power of a big cat. This unusual balance made New Zealand’s ecosystem both unique and fragile. When mammals finally arrived—first with humans, then with rats, dogs, and stoats—the balance was shattered. The story of moa and Haast’s eagle is a poignant illustration of how quickly a delicate system can unravel.

Modern Science Meets Ancient Mystery

Today, researchers use cutting-edge technology to unlock the secrets of these prehistoric birds. CT scans allow scientists to examine the braincases of Haast’s eagle, shedding light on its hunting strategies and sensory abilities. 3D modeling brings these extinct creatures to life, letting us visualize their movements and behaviors. Genetics is even opening the door to the possibility of de-extinction, though the ethical and ecological implications remain hotly debated. The past is no longer silent; every year, new discoveries bring us closer to understanding these giants and their world.

Lessons from Extinction: Echoes for Our Future

The disappearance of moa and Haast’s eagle holds a mirror to our own age. Their fate warns us about the consequences of rapid environmental change and the fragile connections that bind all living things. Conservationists look to this story as a lesson in humility and responsibility—what happens when we ignore the warning signs, and how quickly the wonders of nature can be lost. The ghosts of New Zealand’s lost giants remind us to tread lightly and cherish the wild places that still remain.

The Lasting Legacy: Memory in the Land

Though moa and Haast’s eagle are gone, their influence endures in the forests, mountains, and minds of New Zealanders. Their bones enrich the soil, their stories inspire art and literature, and their shadows flicker in the dreams of all who love wild things. The world they inhabited may be lost, but their legacy remains a testament to the wild creativity of evolution and the enduring power of nature’s dramas.