Scientists assumed for decades that the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) was one widespread species along Mexico’s Pacific coast, all the way to Venezuela, and across the Caribbean. But a revolutionary genetic study has destroyed that illusion by finding that two relict populations are completely separate species lurking in plain sight on the islands of Banco Chinchorro and Cozumel.

Appearing in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, the study reveals a staggering example of evolutionary divergence, illustrating how even studied predators have yet to surprise. With fewer than 1,000 breeding individuals, these new crocodiles pose critical conservation problems and their identification can redefine our knowledge about wildlife in the Caribbean.

Hidden in Plain Sight: How DNA Exposed the Mystery

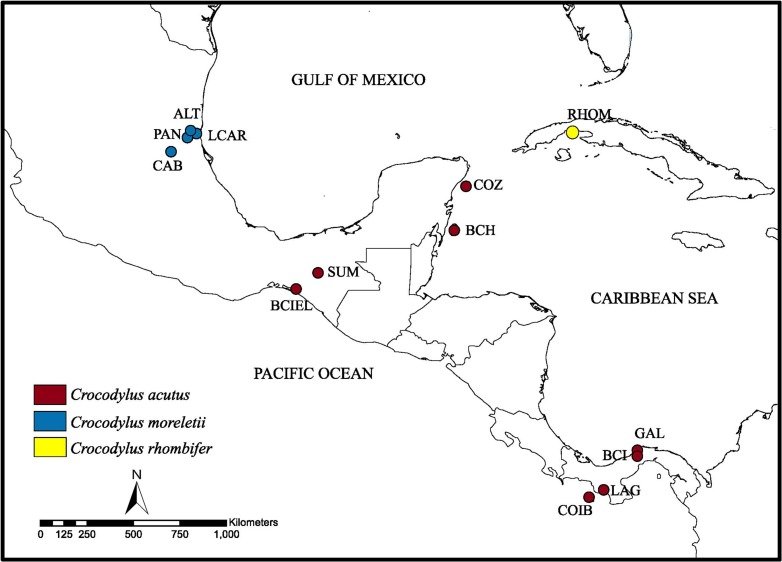

The discovery was made when an international group of biologists, headed by Dr. Hans Larsson and Dr. José Avila-Cervantes, took blood and scale samples from crocodiles on Cozumel and Banco Chinchorro. They compared their genomes to those on the mainland and discovered stark genetic differences much larger than would be expected for a single species.

“This wasn’t just a slight variation,” explains Avila-Cervantes. “The divergence was significant enough to classify them as separate species.” While they haven’t yet been formally named, preliminary findings suggest these crocodiles may have been isolated for thousands of years, evolving unique adaptations to their island environments.

Island Evolution: Why These Crocodiles Are Different

Isolation is a strong force that can form species. Differently from their relatives on the mainland, Cozumel and Banco Chinchorro crocodiles have evolved different physical and genetic characteristics perhaps as a result of reduced gene flow and special ecological pressures.

For example, preliminary observations suggest the Cozumel crocodiles are slightly smaller, with broader snouts a possible adaptation to hunting in dense mangrove forests. Meanwhile, those on Banco Chinchorro, a coral atoll with scarce freshwater, may have evolved a higher salt tolerance.

“Islands are natural laboratories for evolution,” says Larsson. “These crocodiles didn’t just get stranded, they adapted in ways we’re only beginning to understand.”

A Race Against Time: Conservation Challenges Ahead

Both of the recently discovered species live in delicate, limited environments. Cozumel, as a tourist favorite, is beset by speeding coastal development, whereas Banco Chinchorro’s remote location presents some protection but not immunity to climate change and poaching.

With fewer than 1,000 mature individuals each, these crocodiles now join the ranks of critically endangered species. “Their survival hinges on immediate habitat protection,” warns Avila-Cervantes. “Without intervention, we could lose them before we even fully document them.”

Why This Discovery Changes Everything

This finding doesn’t just add two new names to the crocodile family tree it challenges long-held assumptions about Caribbean biodiversity. If crocodiles, large and well-studied, could remain undetected for so long, what else might be hiding in the region’s ecosystems?

“We’ve underestimated the diversity of neotropical reptiles,” says Larsson. “This discovery underscores how much we still don’t know even about apex predators.”

What’s Next? Naming, Protecting, and Further Research

Prior to the official classification of these crocodiles, scientists need to carry out additional morphological and behavioral research. The naming procedure will probably commemorate their geographical origin or distinguishing characteristic as how the Crocodylus moreletii (Morelet’s crocodile) was named in the 19th century.

Meanwhile, conservationists are pushing for stricter protections on both islands, including habitat corridors and restrictions on coastal construction. “Science moves fast, but extinction moves faster,” Larsson emphasizes. “We can’t afford to wait.”

The Bigger Picture: A Lesson in Biodiversity

This find is a harsh reminder: even in a era of high-level genetics, nature retains its secrets. With DNA sequencing growing more widespread, scientists expect additional “hidden” species to pop up especially in remote or under-explored areas.

For now, the focus remains on ensuring these ancient predators don’t vanish before we fully understand them. After all, as Larsson puts it: “You can’t protect what you don’t know exists.”

Final Thought

The revelation of two new crocodile species is more than a scientific milestone; it’s a wake-up call. With habitat loss and climate change accelerating, the race to document and protect Earth’s biodiversity has never been more urgent. And if crocodiles, some of the planet’s most resilient creatures, are at risk, what does that mean for everything else?

One thing is certain: the Caribbean’s waters and its wild secrets are far from fully explored.

Sources :

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.