Imagine walking into a room where every assumption about human culture, race, and identity is being turned upside down. At the dawn of the twentieth century, a small group of passionate outsiders—immigrants, women, and other marginalized voices—gathered around a German-born scholar named Franz Boas. Together, they would revolutionize the field of anthropology in America, shattering old beliefs and inspiring a new wave of scientific understanding. Their radical ideas were not only shocking at the time but would go on to shape how we see ourselves and others even today.

The World Before Boasian Anthropology

Before the Boasians entered the scene, anthropology in America was dominated by rigid, hierarchical thinking. Scholars believed that human societies could be ranked from “primitive” to “advanced,” with white Europeans at the top. These ideas were used to justify racism, colonialism, and a host of social injustices. Anthropology was largely an armchair pursuit, relying on secondhand reports and deeply colored by prejudice. It was a world where outsiders—immigrants, women, and people of color—rarely had a voice in shaping the conversation.

Franz Boas: The Reluctant Revolutionary

Franz Boas arrived in the United States in the late nineteenth century, bringing with him a background in physics and geography. At first glance, he didn’t fit the mold of a revolutionary. Yet Boas was driven by a restless curiosity and a fierce commitment to truth. He began to question the prevailing narratives about race and culture, insisting on the importance of careful observation and firsthand fieldwork. Boas saw the beauty and complexity in every human society, arguing that no culture was inherently superior to another. This belief would become the foundation for a new kind of anthropology.

The Power of Fieldwork and Participant Observation

One of the Boasians’ greatest contributions was their insistence on fieldwork—immersing themselves in the communities they studied. Rather than relying on stereotypes or distant reports, they lived among Native Americans, African Americans, immigrants, and other marginalized groups. They learned languages, participated in rituals, and listened deeply. This approach revealed the richness and nuance of human experience, challenging old assumptions and giving voice to those who had long been ignored. Through their journals and stories, the Boasians showed that real understanding could only come from genuine, empathetic engagement.

Cultural Relativism: A Groundbreaking Idea

Perhaps the most shocking idea the Boasians introduced was cultural relativism—the notion that every culture must be understood on its own terms, not judged by the standards of another. This was a radical departure from the ethnocentrism of the time. Boas and his students argued that customs, beliefs, and values are products of unique historical and environmental contexts. They urged scholars and the public alike to let go of judgment and embrace humility. Cultural relativism became a powerful tool for dismantling prejudice and promoting respect for diversity, a legacy that resonates in today’s multicultural societies.

Challenging the Myth of Race

The Boasians did not shy away from controversy. They boldly confronted the pseudoscientific notion of race, which claimed that physical differences marked unbridgeable divisions between peoples. Through meticulous research, Boas and his students demonstrated that so-called racial traits were not fixed or destiny. They found more variation within groups than between them and showed how environment and culture shaped human development. Their findings laid the groundwork for modern genetics and sparked a wider reckoning with racism in science and society.

Women and Outsiders at the Forefront

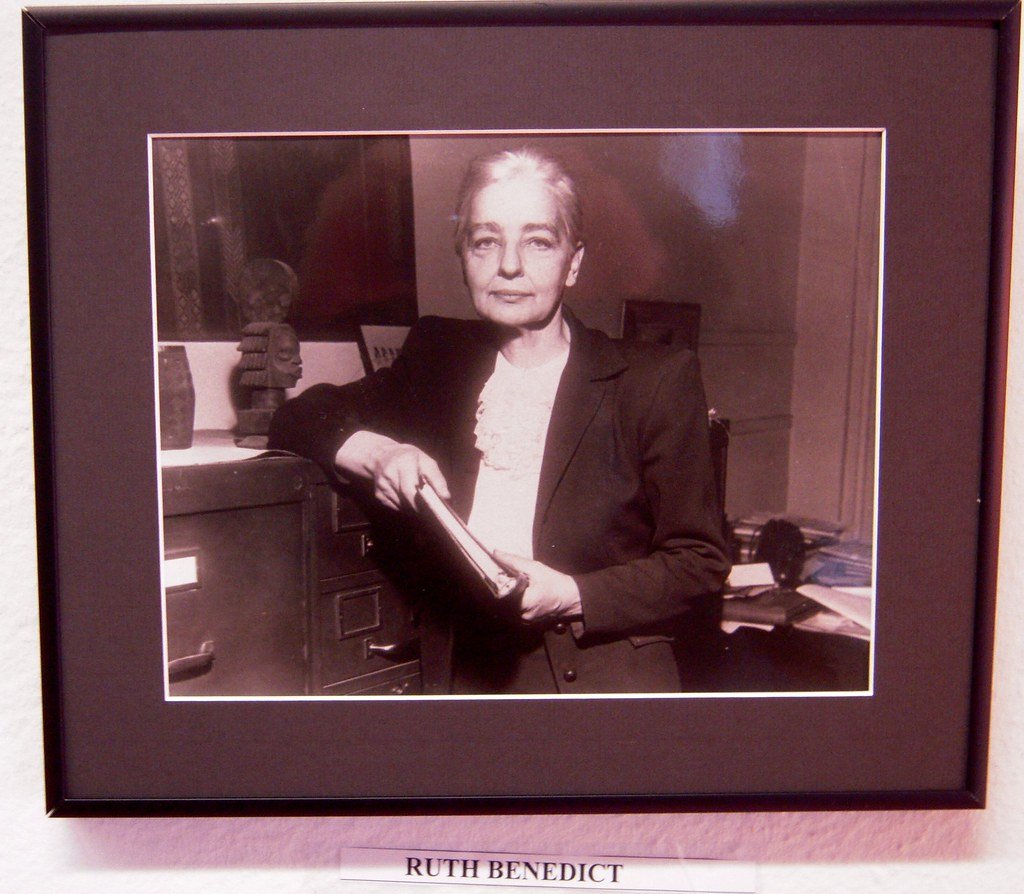

Unlike many scientific circles of their era, the Boasian community welcomed diversity. Women such as Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead, and Zora Neale Hurston played leading roles, breaking barriers and bringing new perspectives. Their outsider status gave them a unique sensitivity to issues of power, identity, and inequality. They explored topics like adolescence, gender, and the complexities of cultural change with a depth and empathy rarely seen before. Their work inspired generations of scholars and activists, reminding us of the strength found in difference.

Ruth Benedict: The Poet of Patterns

Ruth Benedict, a poet at heart, approached anthropology with a sense of wonder. She saw cultures as intricate patterns—each with its own rhythms, contradictions, and beauty. In her groundbreaking book “Patterns of Culture,” Benedict argued that every society develops its own unique style, shaping the personalities and lives of its members. She compared cultures to works of art, each deserving appreciation and respect. Benedict’s poetic sensibility helped humanize anthropology, making it more accessible and inspiring to the public.

Margaret Mead and the Study of Adolescence

Margaret Mead became a household name in the 1920s with her bold study of adolescence in Samoa. She challenged the idea that teenage turmoil was universal, showing instead how culture shapes experience. Mead’s work sparked fierce debates and brought anthropology into the public eye. Her vivid storytelling and willingness to tackle taboo subjects opened doors for future research on gender, sexuality, and social change. Mead’s legacy lives on in every parent, teacher, and scientist who asks how society shapes who we become.

Zora Neale Hurston: Giving Voice to the Margins

Zora Neale Hurston was both an anthropologist and a celebrated writer. Born in the American South, she brought a deep understanding of African American life to her research. Hurston’s fieldwork in the rural South and the Caribbean captured the humor, pain, and resilience of communities often overlooked by mainstream scholars. Her vibrant prose and sharp insights challenged stereotypes and celebrated the richness of Black culture. Hurston remains a symbol of the power of storytelling to transform science and society.

The Boasian Legacy in Modern Anthropology

The impact of the Boasians can still be felt in anthropology classrooms and research around the world. Their insistence on fieldwork, cultural relativism, and respect for diversity continues to shape how we study and understand human societies. Today, anthropologists build on their work to explore issues like migration, globalization, and social justice. The Boasian spirit encourages us to listen, learn, and question—pushing us to see the world through many different eyes.

Shaking the Foundations of Science and Society

The Boasians did more than transform a field; they changed how people think about difference and belonging. Their ideas challenged political leaders, educators, and the general public to confront prejudice and seek understanding. In a world still grappling with racism, xenophobia, and cultural conflict, their message is as urgent as ever: every society has its own wisdom, and every person has a story worth hearing. The movement that began with a handful of outsiders continues to inspire hope and change.

Final Reflections on the Boasian Revolution

The Boasians showed that real science requires courage—the courage to question what everyone else takes for granted, and the humility to listen to voices on the margins. Their legacy reminds us that understanding others is not just a scientific pursuit, but a deeply human one. What stories are still waiting to be heard, and how might they change us next?