In a revolutionary find along South Africa’s Cape coast, researchers have identified the world’s earliest fossilized pangolin tracks, dating to as much as 140,000 years ago. But here’s the twist: The prehistoric trail was cracked not with high-tech imaging or artificial intelligence, but through the traditional know-how of Namibia’s Indigenous Master Trackers, whose age-old expertise deciphered a mystery of the ages that had frustrated scientists for decades.

The Enigmatic Tracks That Baffled Scientists

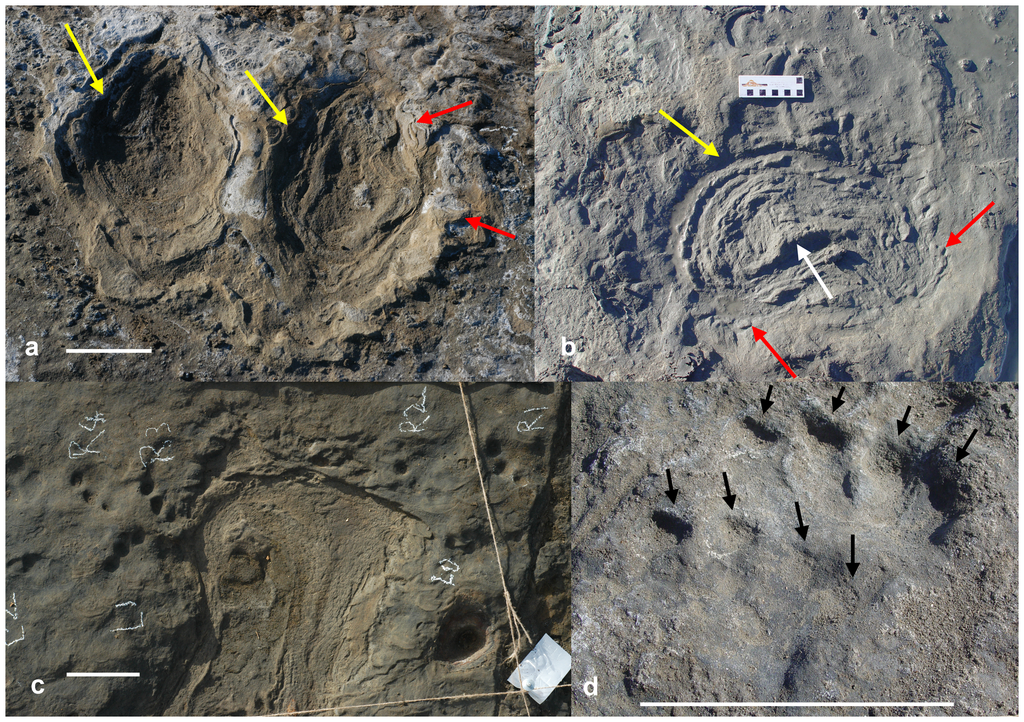

In 2018, a loose slab of aeolianite, a rock formed from ancient windblown sand was discovered near Still Bay in South Africa’s Western Cape. Etched into its surface were eight peculiar tracks, accompanied by faint drag marks, likely left by an animal’s tail. At first, the tracks were a puzzle. Paleontologists Charles Helm, Clive Thompson, and Jan De Vynck examined them but hesitated to draw conclusions. Without clear digit impressions or modern comparisons, the trackmaker remained unknown until Indigenous expertise changed everything.

The Master Trackers Who Cracked the Case

In 2023, the team brought on board two Ju/’hoansi San trackers from Namibia: #Oma Daqm and /Uce Nǂamce, both certified Indigenous Master Trackers with three decades of experience interpreting animal signs in the Kalahari. After studying with care, they rendered a verdict: the tracks were those of a pangolin.

This was a revelation. No fossil pangolin tracks had ever been recorded before, and the discovery rewrote assumptions about the animal’s ancient range. To confirm, researchers used photogrammetry to create 3D models and consulted experts from the African Pangolin Working Group, CyberTracker, and the Tswalu Foundation. The consensus was unanimous the San trackers were right.

What Makes Pangolin Tracks Unique?

Unlike most mammals, pangolins walk primarily on their hind legs, leaving a distinctive trail. Their tracks are rounded at the front, slightly triangular, and lack clear claw marks resembling, as the trackers described, “a round stick poked into the ground.” The tail drags between steps, leaving intermittent scuffs.

The likely trackmaker was Smutsia temminckii, Temminck’s pangolin, which still roams parts of Africa today. Other candidates, like servals, were ruled out due to differences in gait and foot structure.

Dating the Ancient Walkway

The tracks were made when the Cape coast was a vast dune field. Using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) a technique that measures when sediment last saw sunlight geochronologist Andrew Carr dated the rock to between 90,000 and 140,000 years old, during the Pleistocene “Ice Ages.” At the time, sea levels were lower, and the coastline extended up to 100 km farther south than it does today.

Why This Discovery Matters

Other than its scientific interest, this discovery illustrates the potential of combining Western science with Aboriginal wisdom. The tracks may have disappeared forever and their secrets never unraveled but for the San trackers.

It also casts a spotlight on the pangolin’s tragic modern fate. All eight species remaining are threatened because they have been illegally traded for their flesh and scales, consumed in conventional medicine. It is a distant clue, yet grim reminder, of how much time pangolins have wandered upon Earth and of how nearly extinct they remain.

The Future of Fossil Tracking

With funding from the Discovery Wilderness Trust, the San trackers have made their way back to the Cape coast, discovering even more secrets of the Pleistocene. Their unparalleled expertise continues to transform paleontology, demonstrating that some of science’s most significant advancements don’t always emerge from the lab but through centuries of know-how passed through the art of tracking.

As researchers and Indigenous specialists work together more and more, who knows what other lost stories will be unearthed from the sands of time? One thing is for sure: the past holds more secrets yet, and sometimes the best way to learn them is by walking in the footsteps of those who’ve been interpreting the Earth’s oldest signs for thousands of years.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.